IN-DEPTH

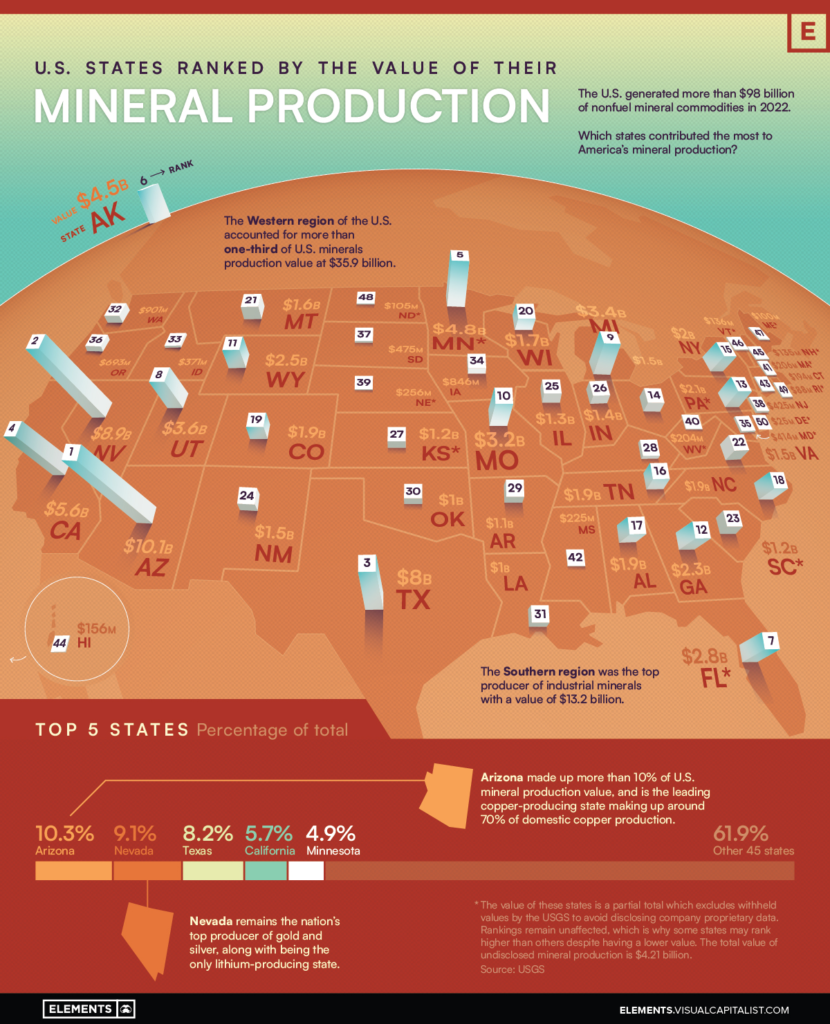

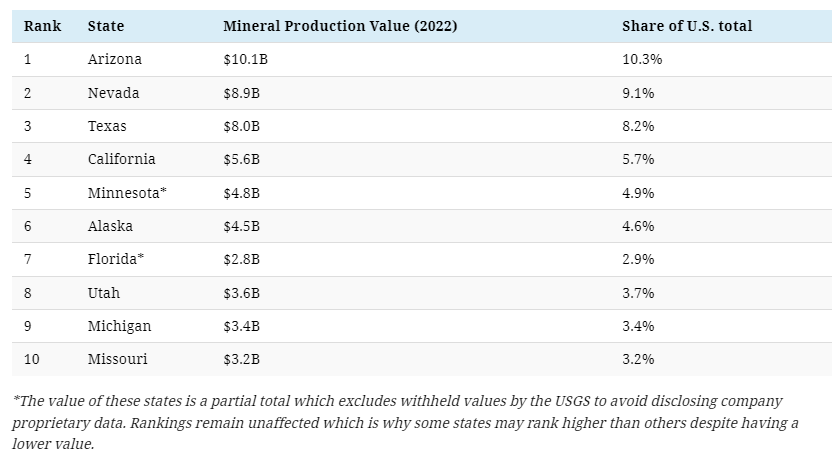

How big is the mercury threat posed by Hudson Bay’s thawing permafrost?

The warming of North America's largest peatland is sending mercury into soil and water. But it's not clear how much there is, exactly how it becomes toxic and how much to worry

As Hudson Bay permafrost thaws, mercury is finding its way into the soil and water, where microbes can convert inorganic mercury into the form to be concerned about: neurotoxic methylmercury.

Photo: Don Johnston_NC / Alamy

This article was originally published on Hakai Magazine.

Covering nearly the same area as Norway, the Hudson Bay Lowlands in northern Ontario and Manitoba is home to the southernmost continuous expanse of permafrost in North America. Compared with many marine waterways this far south, Hudson Bay stays frozen late into the summer, its ice-covered surface reflecting sunlight and keeping the surrounding area cold.

The influence of Hudson Bay on the weather is crazy, says Adam Kirkwood, a graduate student at Carleton University in Ottawa. “It can be sunny and 20 C one day in August, and then half an hour later there’s a wicked wind coming in from the bay — it’s 5 C, and you’re putting on all your layers, and you’re still freezing cold. And when it’s neither of those two things,” he says, “it’s very, very buggy.”

Trapped in all that permafrost is 30 billion tonnes of carbon. It’s an unfathomable amount, says Kirkwood. With global warming, the permafrost is thawing, threatening to release a “carbon bomb” of heat-trapping methane gas to the atmosphere. But there’s something else lurking in the permafrost, too. Something that has the potential to be more immediately dangerous to the people and wildlife living in the area: mercury.

Wildfires and volcanoes belch mercury and since the Industrial Revolution so, too, do coal-burning power plants and factories. Warm air currents carry mercury in its inorganic heavy metal form to the Arctic where it settles into the soil and vegetation before being safely locked away in the deeply frozen permafrost.

In its inorganic form, mercury is less threatening to people. But as the permafrost thaws, says Kirkwood, mercury is finding its way into the soil and into the regions’ many ponds, rivers and lakes. Once there, microbes can convert inorganic mercury into the form to be concerned about: neurotoxic methylmercury.

For the Indigenous peoples of northern Ontario who have lived off the peatlands for thousands of years — hunting caribou, catching fish, and gathering native plants — the lurking threat poses a risk to their way of life.

So for the past six years, Kirkwood has been coming to this remote environment every summer, helicoptering in to drill thick cores of peat and bringing them back to his lab for analysis. On these trips, Kirkwood often has help from Sam Hunter, a self-taught independent scientist from Peawanuck, Ont., who is a member of Weenusk First Nation.

“Muskox has disappeared,” self-taught Cree scientist Sam Hunter says. Hunter accompanies researchers on their fieldwork and brings their findings back to local communities, to integrate Western science and Indigenous Knowledge. Photo: Pat Kane / The Narwhal

Back in the 1970s, Hunter saw how scientists studying the Hudson Bay Lowlands used Indigenous peoples as guides, but didn’t involve them in their research. Now, he says, there’s a co-management process — he accompanies researchers on their fieldwork and helps bring their findings back to local communities. Bringing together outside scientists and traditional knowledge is important, he says, because Indigenous peoples have seen firsthand how the permafrost is changing.

“Walking on permafrost is like walking on really hard ground, like gravel,” says Hunter. When there’s permafrost, he says, “there’s all kinds of flora. There’s berries, vegetation that animals feed on. We collect wild tea.”

But once the permafrost thaws, he says, “the environment turns into a swampland … You can’t even walk, you’d sink.” Along with the disappearing permafrost “go the animals. They move higher and higher into the Arctic. Muskox has disappeared and a few shorebirds we used to have — they’re moving north.”

Methylmercury seeping out of the permafrost is the latest water-quality issue First Nations communities in the region have faced. Closer to the Manitoba border, industrial mercury pollution from the 1960s still affects 90 percent of the Anishinaabe community Grassy Narrows. Many First Nations communities across Canada still lack clean drinking water. In the absence of government support for water-quality testing, Hunter has trained three community members in Peawanuck to test their water and fish.

Whether all of the mercury idling in the permafrost will become a significant threat to locals hinges on the answers to a few outstanding questions — questions Kirkwood aims to answer.

A decade ago, scientists discovered that certain microbes with a specific gene can convert inorganic mercury into toxic methylmercury. Scientists know some microbes have this ability and others don’t, but efforts to relate the abundance of microbes with mercury methylating potential to the amount of methylmercury in the environment have been unsuccessful. That’s led scientists studying mercury cycling, like Andrea Bravo at the Institute of Marine Sciences in Spain, to theorize that there’s more at play dictating the pace of methylmercury production, like the complex relationships between the entire community of microbes in the soil.

Thermokarst fens are meltwater ponds created when iceberg-like permafrost chunks thaw. There, levels of neurotoxic methylmercury levels are higher than in the surroundings.

Photo: Milan Sommer / Shutterstock

That’s where Kirkwood’s research comes in. By drilling and taking core samples of the permafrost, then measuring the amount of inorganic mercury while at the same time sequencing the DNA of everything in the soil, he hopes to better understand how methylmercury gets produced in thawing permafrost. Once he knows that, he can figure out where the threat is largest by looking at where mercury methylating microbes and inorganic mercury overlap.

“It’s a hot topic, a timely research question,” says Bravo, who isn’t involved in Kirkwood’s research. “We are suddenly having a surface of soil that was not reactive before, and it’s becoming reactive. … We don’t know how much mercury is coming from this permafrost.”

Bravo points out there are still many unknowns in efforts to gauge the mercury threat. For one, it’s still not yet possible to accurately predict methylmercury levels in freshwater waterways or the ocean based on land sources. Despite global research efforts, “we still don’t understand the process completely,” she says. “We’ve put in a lot of effort, but we aren’t there yet.”

So far, Kirkwood’s initial findings show reason for hope. Previous Arctic-scale estimates of inorganic mercury abundance have vastly overestimated how much mercury is being stored in the Hudson Bay Lowlands. Kirkwood’s cores show mercury levels 10 times lower. But that doesn’t mean all is well. In thermokarst fens, meltwater ponds created when iceberg-like permafrost chunks thaw, methylmercury levels are higher than in the surroundings.

As more permafrost thaws and these ponds connect, methylmercury production will likely increase. And if this mercury reaches the bay, biomagnification could cause it to build up to high concentrations, making its way up the food chain from algae to the tissue of fish that people catch and eat.

One of the things Hunter says he’s been told by the scientists who come up from the south is that the polar bear is the barometer for climate change. “And I don’t agree with that. I think the barometer for climate change is the palsa, the melting permafrost,” he says. “And I think that we need to understand what’s coming out of the ground now.”