We Need to Talk about Private Forest Lands

A gap in government protection is undermining Indigenous rights and environmental protection.

Michael Ekers, Estair Van Wagner and Sarah Morales 16 Mar 2023TheTyee.ca

Michael Ekers is an associate professor in the department of geography and planning at the University of Toronto. Estair Van Wagner is an associate professor at Osgoode Hall Law School, York University. Sarah Morales is an associate professor at the University of Victoria faculty of law, where Van Wagner is currently a visiting professor

Large swaths of private forest lands — especially on Vancouver Island — aren’t protected from harmful logging practices. Photo by TJ Watt.

The B.C. government has been roundly applauded for removing a key word from the provincial regulations governing forest planning.

For two decades the word “unduly” has limited the protection of so-called “non-timber” values in B.C. forests. Wildlife habitat, soil, biodiversity and even drinking water could only be protected if it did not “unduly reduce the supply of timber from British Columbia.”

This gave government, and the industry players with the ear of decision-makers, a statutory trump card to maintain timber supply despite calls for stronger biodiversity, wildlife and old-growth protection. As others have noted, this has been a barrier to sound and sustainable forest legislation despite growing evidence that healthy forests are crucial to addressing climate change.

While “unduly” has not been removed from all forestry regulations (it remains in the Government Action Regulations restricting the protection of a range of environmental and recreation values), this is a clear step forward. Alongside further old-growth protection and a stronger role for Indigenous peoples in forest planning, these regulatory changes signal the potential for a new direction in forest governance.

Nevertheless, crucial questions remain about the future of forests in B.C.

The Forest Range and Practices Act was critical to the deregulation of the provincial logging industry in the 2000s. However, the legislation specific to private forest lands went much further. In 2003, a year before the former BC Liberal government introduced the unduly clauses into forestry regulation on public lands, the Private Managed Forest Lands Act was enacted. The private land forestry regime prescribes no limits to the annual harvest or the size of clear cuts. It makes no reference to constitutionally protected Aboriginal rights and title.

If you were TimberWest or Island Timberlands, the largest owners of private forest land in the province, you could literally cut at will so long as you met five weakly defined “management commitments.” The two companies did just that, pushing up harvest levels to unprecedented highs before they came crashing down during the sub-prime mortgage crisis. And all this extraction resulted in limited employment benefits because raw log exports are allowed from much of this land.

After years of public outcry, litigation and concerns from Indigenous nations, the John Horgan government initiated a review of the Private Managed Forest Lands program in 2019. The process included a call for public engagement.

The B.C. government has been roundly applauded for removing a key word from the provincial regulations governing forest planning.

For two decades the word “unduly” has limited the protection of so-called “non-timber” values in B.C. forests. Wildlife habitat, soil, biodiversity and even drinking water could only be protected if it did not “unduly reduce the supply of timber from British Columbia.”

This gave government, and the industry players with the ear of decision-makers, a statutory trump card to maintain timber supply despite calls for stronger biodiversity, wildlife and old-growth protection. As others have noted, this has been a barrier to sound and sustainable forest legislation despite growing evidence that healthy forests are crucial to addressing climate change.

While “unduly” has not been removed from all forestry regulations (it remains in the Government Action Regulations restricting the protection of a range of environmental and recreation values), this is a clear step forward. Alongside further old-growth protection and a stronger role for Indigenous peoples in forest planning, these regulatory changes signal the potential for a new direction in forest governance.

Nevertheless, crucial questions remain about the future of forests in B.C.

The Forest Range and Practices Act was critical to the deregulation of the provincial logging industry in the 2000s. However, the legislation specific to private forest lands went much further. In 2003, a year before the former BC Liberal government introduced the unduly clauses into forestry regulation on public lands, the Private Managed Forest Lands Act was enacted. The private land forestry regime prescribes no limits to the annual harvest or the size of clear cuts. It makes no reference to constitutionally protected Aboriginal rights and title.

If you were TimberWest or Island Timberlands, the largest owners of private forest land in the province, you could literally cut at will so long as you met five weakly defined “management commitments.” The two companies did just that, pushing up harvest levels to unprecedented highs before they came crashing down during the sub-prime mortgage crisis. And all this extraction resulted in limited employment benefits because raw log exports are allowed from much of this land.

After years of public outcry, litigation and concerns from Indigenous nations, the John Horgan government initiated a review of the Private Managed Forest Lands program in 2019. The process included a call for public engagement.

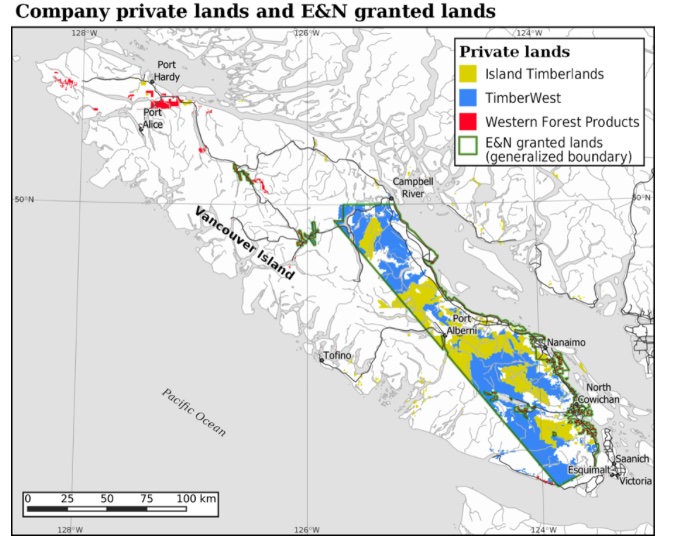

Private forest lands make up a large part of Vancouver Island. Mosaic Forest Management is now the manager of the holdings of Island Timberlands and TimberWest.

However, the province failed to adequately consult with the Indigenous nations impacted by the Private Managed Forest Lands Act. This failure was particularly glaring for Vancouver Island nations with territory overlapping the vast belt of private forest lands created from the late 19th century E&N Railway land grants. For example, the E&N grants converted roughly 85 per cent of the territory of the Hul’qumi’num Treaty Group to private land without consent or compensation. Today 60 per cent of the territory is held by private forest companies. This concentration of private land has had profound effects on Hul’qumi’num peoples and remains a key roadblock in treaty negotiations.

Meanwhile, a freedom of information release indicates that confidential meetings were held between the government, Private Forest Landowners Association and Mosaic Forest Management, the company that now manages the land holdings of Island Timberlands and TimberWest. The content of these discussions is redacted.

The vast majority of public submissions to the review highlighted concern over high harvesting rates, fear over water quality and biodiversity loss and the lack of government oversight. Yet, nearly four years on, no policy changes have been proposed.

BC’s New Forest Rules: A Small Word Change May Be Big for Saving Trees

However, the province failed to adequately consult with the Indigenous nations impacted by the Private Managed Forest Lands Act. This failure was particularly glaring for Vancouver Island nations with territory overlapping the vast belt of private forest lands created from the late 19th century E&N Railway land grants. For example, the E&N grants converted roughly 85 per cent of the territory of the Hul’qumi’num Treaty Group to private land without consent or compensation. Today 60 per cent of the territory is held by private forest companies. This concentration of private land has had profound effects on Hul’qumi’num peoples and remains a key roadblock in treaty negotiations.

Meanwhile, a freedom of information release indicates that confidential meetings were held between the government, Private Forest Landowners Association and Mosaic Forest Management, the company that now manages the land holdings of Island Timberlands and TimberWest. The content of these discussions is redacted.

The vast majority of public submissions to the review highlighted concern over high harvesting rates, fear over water quality and biodiversity loss and the lack of government oversight. Yet, nearly four years on, no policy changes have been proposed.

BC’s New Forest Rules: A Small Word Change May Be Big for Saving Trees

READ MORE

As important changes are introduced to forestry activities on public land, private forest lands are being left behind. For those on Vancouver Island, this is no small thing. Nearly 600,000 hectares of private forest land lie between Sooke and Campbell River. Without sustainable forest policies we continue to witness the rapid extraction of timber resources, degradation of wildlife habitat and watersheds and low-levels of employment. Indigenous people are unable to exercise their constitutionally protected rights with crucial territories blocked by locked gates and no trespassing signs.

Landowners will likely resist any perceived incursions on their rights to control private property. But property rights are not absolute. They are always governed by a range of policies designed to protect the public interest. Planning rules determine whether you can build a laneway house or whether trees or heritage buildings can be removed. Why should private forest land be any different?

We all have a public interest in the future of these forests. From their centrality to meaningful reconciliation with Indigenous peoples to the role they can play in preventing catastrophic climate change, there is too much at stake to exclude private forest lands from these changes to forest policy.

As important changes are introduced to forestry activities on public land, private forest lands are being left behind. For those on Vancouver Island, this is no small thing. Nearly 600,000 hectares of private forest land lie between Sooke and Campbell River. Without sustainable forest policies we continue to witness the rapid extraction of timber resources, degradation of wildlife habitat and watersheds and low-levels of employment. Indigenous people are unable to exercise their constitutionally protected rights with crucial territories blocked by locked gates and no trespassing signs.

Landowners will likely resist any perceived incursions on their rights to control private property. But property rights are not absolute. They are always governed by a range of policies designed to protect the public interest. Planning rules determine whether you can build a laneway house or whether trees or heritage buildings can be removed. Why should private forest land be any different?

We all have a public interest in the future of these forests. From their centrality to meaningful reconciliation with Indigenous peoples to the role they can play in preventing catastrophic climate change, there is too much at stake to exclude private forest lands from these changes to forest policy.

No comments:

Post a Comment