by Patrick D. Nunn, The Conversation

Can you imagine a scientist who could neither read nor write, who spoke their wisdom in riddles, in tales of fantastic beings flying through the sky, fighting each another furiously and noisily, drinking the ocean dry, and throwing giant spears with force enough to leave massive holes in rocky headlands?

Our newly published research in the journal Oral Tradition shows memories of a volcanic eruption in Fiji some 2,500 years ago were encoded in oral traditions in precisely these ways.

They were never intended as fanciful stories, but rather as the pragmatic foundations of a system of local risk management.

Life-changing events

Around 2,500 years ago, at the western end of the island of Kadavu in the southern part of Fiji, the ground shook, the ocean became agitated, and clouds of billowing smoke and ash poured into the sky.

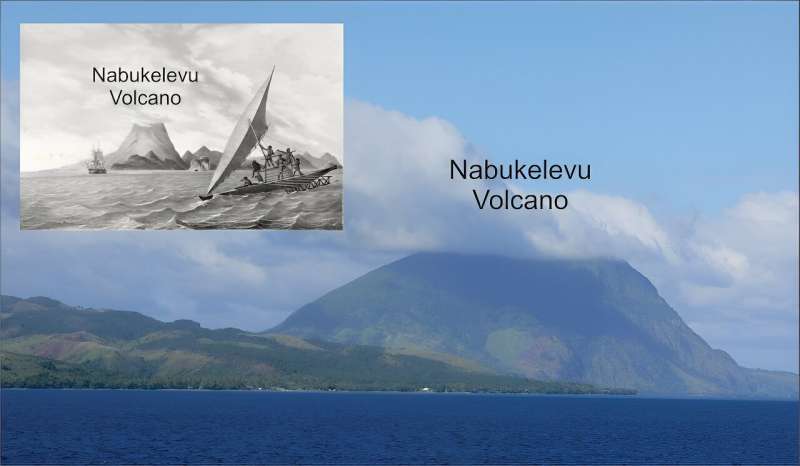

When the clouds cleared, the people saw a new mountain had formed, its shape resembling a mound of earth in which yams are grown. This gave the mountain its name—Nabukelevu, the giant yam mound. (It was renamed Mount Washington during Fiji's colonial history.)

So dramatic, so life-changing were the events associated with this eruption, the people who witnessed it told stories about it. These stories have endured more than two millennia, faithfully passed on across roughly 100 generations to reach us today.

Scientists used to dismiss such stories as fictions, devalue them with labels like "myth" or "legend". But the situation is changing.

Today, we are starting to recognize that many such "stories" are authentic memories of human pasts, encoded in oral traditions in ways that represent the worldviews of people from long ago.

Nabukelevu from the northeast, its top hidden in cloud. Inset: Nabukelevu from the west in 1827 after the drawing by the artist aboard the Astrolabe, the ship of French explorer Dumont d’Urville. It is an original lithograph by H. van der Burch after original artwork by Louis Auguste de Sainson. Credit: Wikimedia Commons; Australian National Maritime Museum, CC BY-SA

Nabukelevu from the northeast, its top hidden in cloud. Inset: Nabukelevu from the west in 1827 after the drawing by the artist aboard the Astrolabe, the ship of French explorer Dumont d’Urville. It is an original lithograph by H. van der Burch after original artwork by Louis Auguste de Sainson. Credit: Wikimedia Commons; Australian National Maritime Museum, CC BY-SAIn other words, these stories served the same purpose as scientific accounts, and the people who told them were trying to understand the natural world, much like scientists do today.

Battle of the vu

The most common story about the 2,500-year-old eruption of Nabukelevu is one involving a "god" (vu in Fijian) named Tanovo from the island of Ono, about 56km from the volcano.

Tanovo's view of the sunset became blocked one day by this huge mountain. Our research identifies this as a volcanic dome that was created during the eruption, raising the height of the mountain several hundred feet.

Enraged, Tanovo flew to Nabukelevu and started to tear down the mountain, a process described by local residents as driva qele (stealing earth). This explains why even today the summit of Nabukelevu has a crater.

But Tanovo was interrupted by the "god" of Nabukelevu, named Tautaumolau. The pair started fighting. A chase ensued through the sky and, as the two twisted and turned, the earth being carried by Tanovo started falling to the ground, where it is said to have "created" islands.

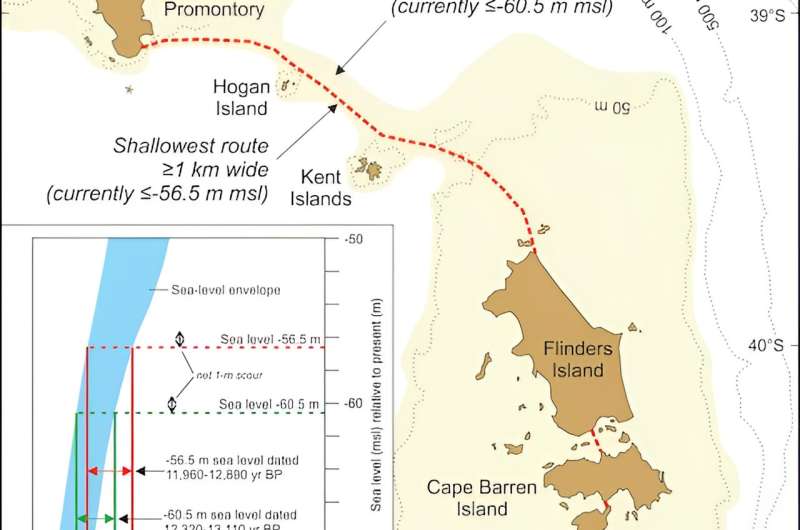

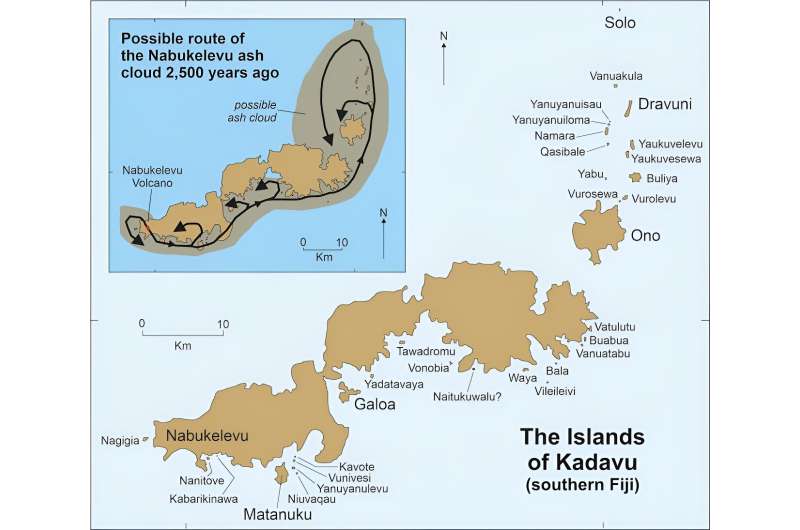

We conclude that the sequence in which these islands are said to have been created is likely to represent the movement of the ash plume from the eruption, as shown on the map below.

'Myths' based in fact

Geologists would today find it exceedingly difficult to deduce such details of an ancient eruption. But here, in the oral traditions of Kadavu people, this information is readily available.

Another detail we would never know if we did not have the oral traditions is about the tsunami the eruption caused.

In some versions of the story, one of the "gods" is so frightened, he hides beneath the sea. But his rival comes along and drinks up all the water at that place, a detail our research interprets as a memory of the ocean withdrawing prior to tsunami impact.

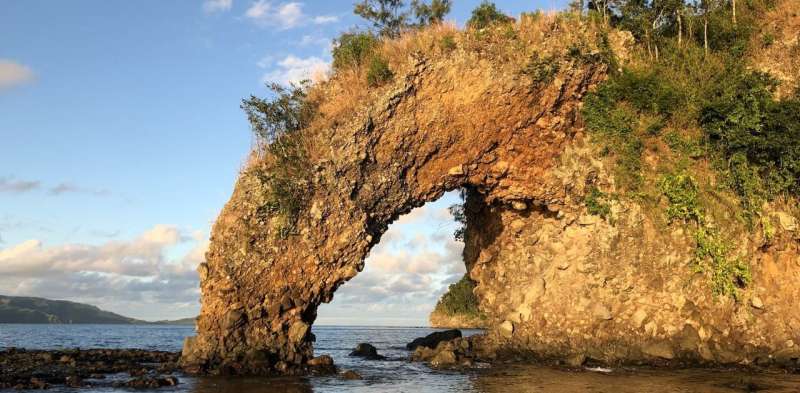

Other details in the oral traditions recall how one god threw a massive spear at his rival but missed, leaving behind a huge hole in a rock. This is a good example of how landforms likely predating the eruption can be retrofitted to a narrative.

Our study adds to the growing body of scientific research into "myths" and "legends", showing that many have a basis in fact, and the details they contain add depth and breadth to our understanding of human pasts.

The Kadavu volcano stories discussed here also show ancient societies were no less risk aware and risk averse than ours are today. The imperative was to survive, greatly aided by keeping alive memories of all the hazards that existed in a particular place.

Australian First Peoples' cultures are replete with similar stories.

Literate people, those who read and write, tend to be impressed by the extraordinary time depth of oral traditions, like those about the 2,500-year old eruption of Nabukelevu. But not everyone is.

In early 2019, I was sitting and chatting to Ratu Petero Uluinaceva in Waisomo Village, after he had finished relating the Ono people's story of the eruption. I told him this particular story recalled events which occurred more than two millennia ago—and thought he might be impressed. But he wasn't.

"We know our stories are that old, that they recall our ancient history," he told me with a grin. "But we are glad you have now learned this too!"

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Explore furtherEvidence the oral stories of Australia's First Nations might be 10,000 years old

James Churchward - Wikipedia

Churchward was born in Bridestow, Okehampton, Devon at Stone House to Henry and Matilda (née Gould) Churchward. James had four brothers and four sisters. In November 1854, Henry died and the family moved in with Matilda's parents in the hamlet of Kigbear, near Okehampton. Census records indicate the family next moved to London when James was 18 after his grandfather George Gould died.

THE SACRED SYMBOLS OF MU - James Churchward

COLONEL JAMES CHURCHWARD AUTHOR OF "THE LOST CONTINENT OF MU" "THE CHILDREN OF MU" ILLUSTRATED IVES WASHBURN; NEW YORK Scanned at sacred-texts.com, December, 2003.

3 Beards Podcast: Is the Lost Continent of Mu Real?

Author Jack Churchward joins the show to talk about his books that cover The Lost Continent of Mu, a subject brought to life by the works of his great grandfather Col. James Churchward.

Lifting the Veil on the Lost Continent of Mu: The Motherland of Men

The Stone Tablets of Mu

Crossing the Sands of Time

are books Jack Churchward has penned to cover the works of his great grandfather and bring into focus on what is fact and what is fiction.

The mythical idea of the “Land of Mu” first appeared in the works of the British-American antiquarian Augustus Le Plongeon (1825–1908), after his investigations of the Maya ruins in Yucatán. He claimed that he had translated the first copies of the Popol Vuh, the sacred book of the K’iche’ from the ancient Mayan using Spanish. He claimed the civilization of Yucatán was older than those of Greece and Egypt, and told the story of an even older continent.

Col. James Churchward claimed that the landmass of Mu was located in the Pacific Ocean, and stretched east–west from the Marianas to Easter Island, and north–south from Hawaii to Mangaia. According to Churchward the continent was supposedly 5,000 miles from east to west and over 3,000 miles from north to south, which is larger than South America. The continent was believed to be flat with massive plains, vast rivers, rolling hills, large bays, and estuaries. He claimed that according to the creation myth he read in the Indian tablets, Mu had been lifted above sea level by the expansion of underground volcanic gases. Eventually Mu “was completely obliterated in almost a single night” after a series of earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, “the broken land fell into that great abyss of fire” and was covered by “fifty millions of square miles of water.” Churchward claimed the reasoning for the continent’s destruction in one night was because the main mineral on the island was granite and was honeycombed to create huge shallow chambers and cavities filled with highly explosive gases. Once the chambers were empty after the explosion, they collapsed on themselves, causing the island to crumble and sink.