Research estimates that a mere 2% of all chemical exposure has been identified

What chemicals are we exposed to on a daily basis? That is the central question of "non-targeted analysis" or NTA, an emerging field of analytical science that aims to identify all chemicals around us. A daunting task, because how can you be sure to detect everything if you don't know exactly what you're looking for?

In a paper published in Environmental Science and Technology, researchers at the Universities of Amsterdam (UvA, the Netherlands) and Queensland (UQ, Australia) have assessed this problem. In a meta-analysis of NTA results published over the past six years, they estimate that less than 2% of all chemicals have been identified.

According to Viktoriia Turkina who performed the research as a Ph.D. student with Dr. Saer Samanipour at the UvA's Van 't Hoff Institute for Molecular Sciences, this limitation underscores the urgent need for a more proactive approach to chemical monitoring and management. "We need to incorporate more data-driven strategies into our studies to be able to effectively protect the human and environmental health," she says.

Samanipour explains that current monitoring of chemicals is rather limited since it's expensive, time consuming, and requires specialized experts. "As an example, in the Netherlands we have one of the most sophisticated monitoring programs for chemicals known to be of concern to human health. Yet we target less than 1,000 chemicals. There are far more chemicals out there that we don't know about."

A vast chemical space

To deal with those chemicals, some 15 to 20 years ago the concept of non-targeted analysis was introduced to look at possible exposure in an unbiased manner. The idea is to take a sample from the environment (air, water, soil, sewer sludge) or the human body (hair, blood, etc.) and analyze it using well-established techniques such as chromatography coupled with high resolution mass spectroscopy.

The challenge then is to trace the obtained signal back to the structures of chemicals that may be present in the sample. This will include already known chemicals, but also chemicals of which the potential presence in the environment is yet unknown.

In theory, this "chemical space" includes as many as 1060 compounds, an incomprehensible number that exceeds the number of stars in the universe by far. On the other hand, the number of organic and inorganic substances published in the scientific literature and public databases is estimated at around 180 million.

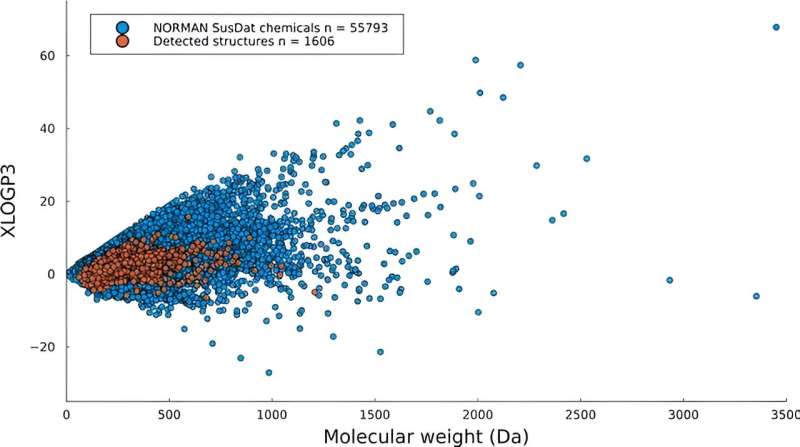

To make their research more manageable, Turkina, Samanipour and co-workers focused on a subset of 60,000 well-described compounds from the NORMAN database. Turkina says, "This served as the reference to establish what is covered in NTA studies, and more importantly, to develop an idea about what is being overlooked."

The vast 'exposome' of chemicals that humans are exposed to on a daily basis is a sign of our times, according to Samanipour.

"These days we are soaking in a giant ocean of chemicals. The chemical industry is part of that, but also nature is running all a whole bunch of reactions that result in exposure. And we expose ourselves to chemicals by the stuff we use—think for instance of the problem of microplastics. To solve all this we have to be able to go beyond pointing fingers. With our research, we hope to contribute to finding a solution together. Because we all are in the same boat."

Much room for improvement

The meta analysis, which included 57 NTA papers, revealed that only around 2% of the estimated chemical space was covered. This can indicate that the actual exposure to chemicals is indeed quite low, however, it can also point to shortcomings in the applied analyses. According to Turkina and Samanipour, the latter is indeed the case. They focused on NTA studies applying liquid chromatography coupled with high resolution mass spectrometry (LC-HRMS) -one of the most comprehensive methods for the analysis of complex environmental and biological samples.

It turned out that there was much room for improvement. For instance in sample preparation, they observed a bias towards specific compounds rather than capturing a more diverse set of chemicals. They also observed poor selection and inconsistent reporting of LC-HRMS parameters and data acquisition methods.

"In general," Samanipour says, "the chemical analysis community is to a great extent driven by the available technology that vendors have developed for specific analysis purposes. Thus the instrumental set-up and data processing methods are rather limited when it comes to non-targeted analysis."

To Samanipour, the NTA approach is definitely worth pursuing. "But we need to develop it further and push it forward. Together with vendors we can develop new powerful and more versatile analytical technologies, as well as effective data analysis protocols."

He also advocates a data-driven approach were the theoretical chemical space is "back calculated" towards a subset of chemicals that are highly likely to be present in our environment. "Basically we have to better understand what is the true chemical space of exposure. And once those boundaries are defined, then it becomes a lot easier to assess that number of 2% we have determined."

More information: Tobias Hulleman et al, Critical Assessment of the Chemical Space Covered by LC–HRMS Non-Targeted Analysis, Environmental Science & Technology (2023). DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.3c03606