Boosting the brain's control of prosthetic devices by tapping the cerebellum

Neuroprosthetics, a technology that allows the brain to control external devices such as robotic limbs, is beginning to emerge as a viable option for patients disabled by amputation or neurological conditions such as stroke. Cedars-Sinai investigators, in a study published in the journal Science Advances, are believed to be the first to show that tapping the power of the cerebellum, a region in the back of the brain, could improve patients' ability to control these devices.

"Neuroprosthetics have largely tapped the brain's outermost cerebral cortex. The cerebellum has a well-known role in movement but has been ignored in neuroprosthetic research," said Tanuj Gulati, Ph.D., assistant professor of Biomedical Sciences and Neurology and researcher in the Center for Neural Science and Medicine at Cedars-Sinai, and senior author of the study.

"We are the first to record what is happening in the cerebellum as the brain learns to manipulate these devices, and we found that its involvement is essential for device use."

Patients who use neuroprosthetic devices have electrodes permanently implanted in the portion of the brain—usually the cerebral cortex—that controls movement for the function the device is replacing. This technique can be used to help patients control a robotic limb, a motorized wheelchair or a computer keyboard, among other devices.

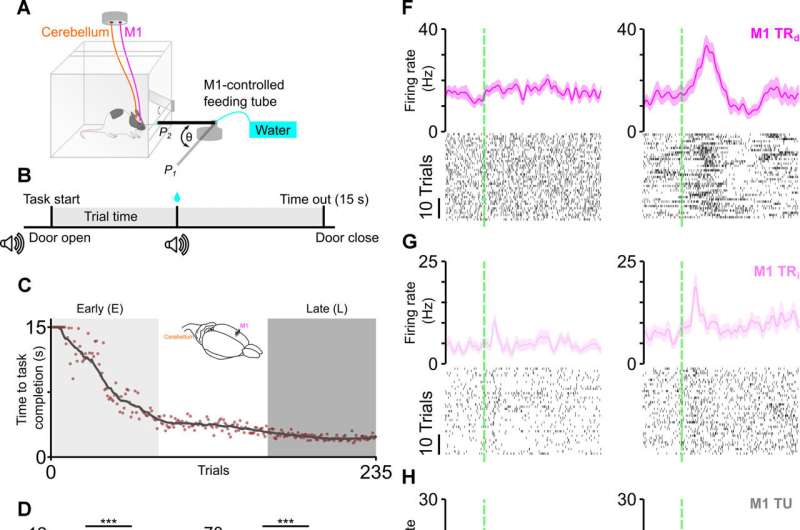

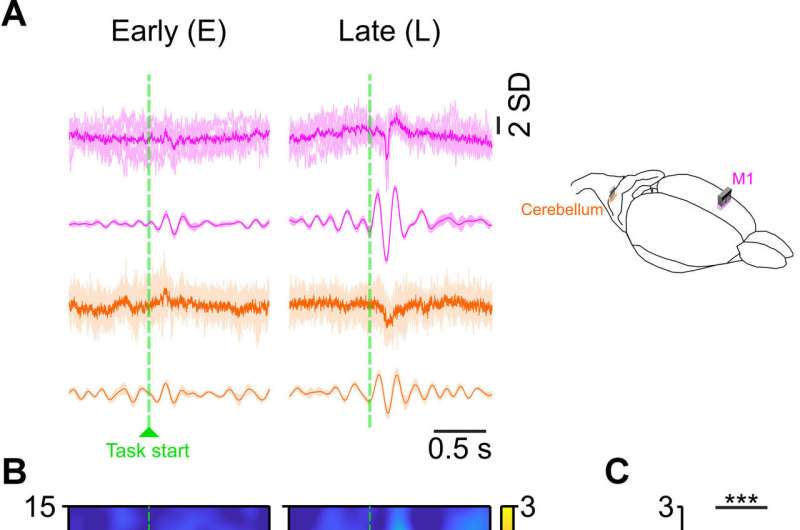

To learn how the cerebellum helps in learning neuroprosthetic control, Gulati and his team trained laboratory rats to use only their motor cortex activity to move a neuroprosthetic tube that delivered them water. The rats had electrodes implanted in the motor cortex and the cerebellum, and investigators listened in on the activity of neurons in both brain regions during the experiments.

"We found that activity of the neurons in the cerebellum was coordinated with the motor cortex, and that activity in the cerebellum was critical for neuroprosthetic task performance," said Aamir Abbasi, Ph.D., a postdoctoral scientist in the Gulati Lab and the first author of the study.

Investigators next used an advanced technology called optogenetics to selectively silence different neuron populations in the laboratory rats' brains during experiments. Optogenetics delivers light-sensitive proteins into brain cells, allowing light exposure to control these cells' activity.

When they silenced neurons in the outer layer of the cerebellum, where the cerebellum receives input from other brain regions, they found that the laboratory rats had a difficult time learning to control movement of the pipe. When they silenced neurons deep in the cerebellum, which are responsible for outward communication from the cerebellum to the motor cortex, the rats had difficulty maintaining accurate control of the pipe.

"These results could help make neuroprosthetics an option for patients with damage to the motor cortex due to brain injury, stroke or diseases such as Parkinson's or multiple sclerosis," said Nancy L. Sicotte, MD, chair of the Department of Neurology and the Women's Guild Distinguished Chair in Neurology at Cedars-Sinai.

"It's possible that, eventually, implants in the cerebellar region could be used to help these patients manipulate external devices."

It's an exciting era for neuroprosthetics, said David Underhill, Ph.D., chair of the Department of Biomedical Sciences at Cedars-Sinai.

"There is a lot of buzz about neuroprosthetic technology, but there are still many unsolved problems," Underhill said. "This study suggests that some of those could be resolved by involving the cerebellum as well as the motor cortex to help patients gain use of neuroprosthetic devices more quickly and improve their ability to control them accurately."

More information: Aamir Abbasi et al, Cortico-cerebellar coordination facilitates neuroprosthetic control, Science Advances (2024). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adm8246