Microplastics make their way from the gut to other organs, researchers find

It's happening every day. From our water, our food and even the air we breathe, tiny plastic particles are finding their way into many parts of our body.

But what happens once those particles are inside? What do they do to our digestive system?

In a recent paper published in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives, University of New Mexico researchers found that those tiny particles—microplastics—are having a significant impact on our digestive pathways, making their way from the gut and into the tissues of the kidney, liver and brain.

Eliseo Castillo, Ph.D., an associate professor in the Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology in the UNM School of Medicine's Department of Internal Medicine and an expert in mucosal immunology, is leading the charge at UNM on microplastic research.

"Over the past few decades, microplastics have been found in the ocean, in animals and plants, in tap water and bottled water," Castillo, explains. "They appear to be everywhere."

Scientists estimate that people ingest 5 grams of microplastic particles each week on average—equivalent to the weight of a credit card.

While other researchers are helping to identify and quantify ingested microplastics, Castillo and his team focus on what the microplastics are doing inside the body, specifically to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and to the gut immune system.

Over a four-week period, Castillo, postdoctoral fellow Marcus Garcia, PharmD, and other UNM researchers exposed mice to microplastics in their drinking water. The amount was equivalent to the quantity of microplastics humans are believed to ingest each week.

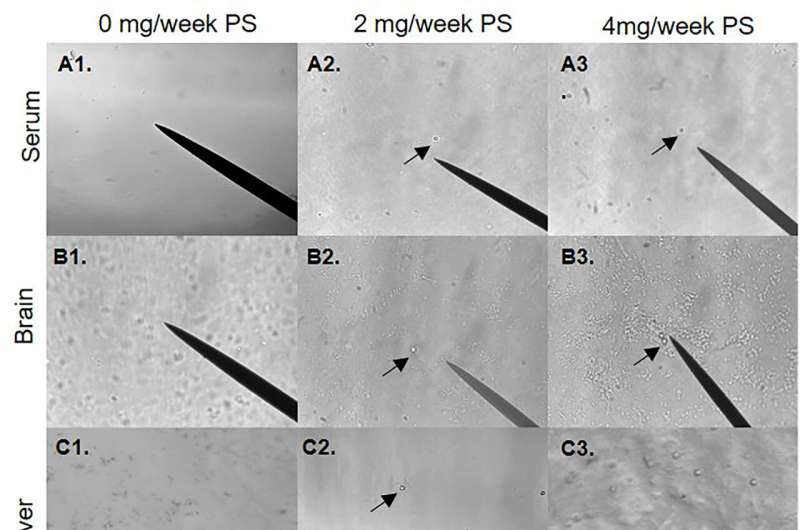

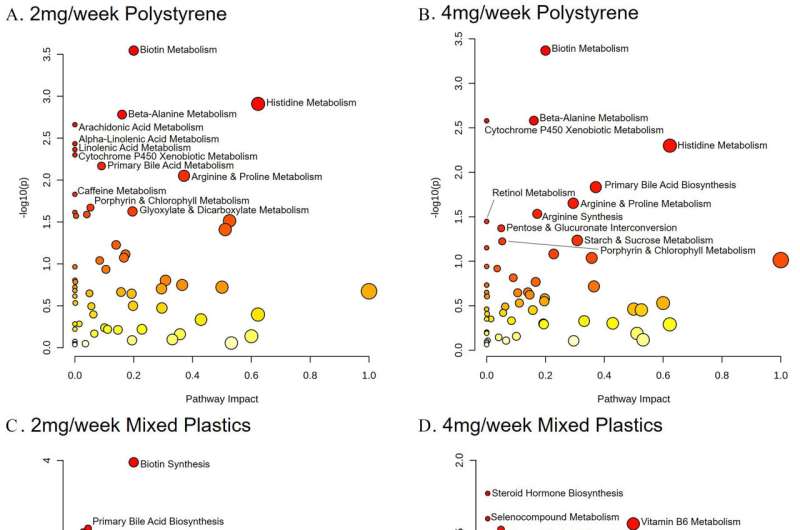

Microplastics had migrated out of the gut into the tissues of the liver, kidney and even the brain, the team found. The study also showed the microplastics changed metabolic pathways in the affected tissues.

"We could detect microplastics in certain tissues after the exposure," Castillo says. "That tells us it can cross the intestinal barrier and infiltrate into other tissues."

Castillo says he's also concerned about the accumulation of the plastic particles in the human body. "These mice were exposed for four weeks," he states. "Now, think about how that equates to humans, if we're exposed from birth to old age."

The healthy laboratory animals used in this study showed changes after brief microplastic exposure, Castillo says. "Now imagine if someone has an underlying condition, and these changes occur, could microplastic exposure exacerbate an underlying condition?"

He has previously found that microplastics are also impacting macrophages—the immune cells that work to protect the body from foreign particles.

In a paper published in the journal Cell Biology & Toxicology in 2021, Castillo and other UNM researchers found that when macrophages encountered and ingested microplastics, their function was altered and they released inflammatory molecules.

"It is changing the metabolism of the cells, which can alter inflammatory responses," Castillo says. "During intestinal inflammation—states of chronic illness such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease, which are both forms of inflammatory bowel disease—these macrophages become more inflammatory and they're more abundant in the gut."

The next phase of Castillo's research, which is being led by postdoctoral fellow Sumira Phatak, Ph.D., will explore how diet is involved in microplastic uptake.

"Everyone's diet is different," he says. "So, what we're going to do is give these laboratory animals a high-cholesterol/high-fat diet, or high-fiber diet, and they will be either exposed or not exposed to microplastics. The goal is to try to understand if diet affects the uptake of microplastics into our body."

Castillo says one of his Ph.D. students, Aaron Romero, is also working to understand why there is a change in the gut microbiota. "Multiple groups have shown microplastics change the microbiota, but how it changes the microbiota hasn't been addressed."

Castillo hopes that his research will help uncover the potential impacts microplastics are having to human health and that it will help spur changes to how society produces and filtrates plastics.

"At the end of the day, the research we are trying to do aims to find out how this is impacting gut health," he notes. "Research continues to show the importance of gut health. If you don't have a healthy gut, it affects the brain, it affects the liver and so many other tissues. So even imagining that the microplastics are doing something in the in the gut, that chronic exposure could lead to systemic effects."

More information: Marcus M. Garcia et al, In Vivo Tissue Distribution of Polystyrene or Mixed Polymer Microspheres and Metabolomic Analysis after Oral Exposure in Mice, Environmental Health Perspectives (2024). DOI: 10.1289/EHP13435

No comments:

Post a Comment