US politics today: Chaos, conflict and a creeping constitutional crisis

First published at Tempest.

Bourgeois electoral politics in the U.S. has entered an epoch of unprecedented instability exemplified by three signal events. First, President Joe Biden’s catastrophic debate and consequent collapse in polls seemed to doom the Democrats to certain defeat. Then, Donald Trump’s near assassination and, by his account, divine salvation followed by his triumphant Republican National Convention appeared to consolidate his lock on the presidency and perhaps the GOP’s capture of both houses of Congress.

Finally, in a desperate move to save their electoral fortunes, the Democrats’ capitalist donors and party bureaucrats intervened to dethrone Biden and coronate Vice President Kamala Harris as their new nominee. Now the election seems to be a dead heat whose outcome is, right now, unpredictable. It will be impacted by all sorts of surprises, domestic and international, between now and November. Whichever party wins, the U.S. will have a divided government, paralyzed and unable to implement the victor’s full program, and faced with intransigent political opposition that will accelerate what has already been a creeping constitutional crisis.

Global political instability

The electoral instability in the U.S. is, in fact, the norm throughout the world. There are few stable democratic or authoritarian regimes anywhere. Why? Because global capitalism’s multiple crises are undermining popular support for states almost without exception.

Just look at the heads of government that met at the most recent G7 summit. All of them, from Biden to Emmanuel Macron to the recently toppled Rishi Sunak, had record-low approval ratings. The same is true of capitalist autocracies, from Russia, where Vladimir Putin faced a coup last year, to China, whose population just a couple of years ago staged mass protests and strikes against Xi Jinping’s draconian Zero Covid policy of lockdowns of homes and workplaces.

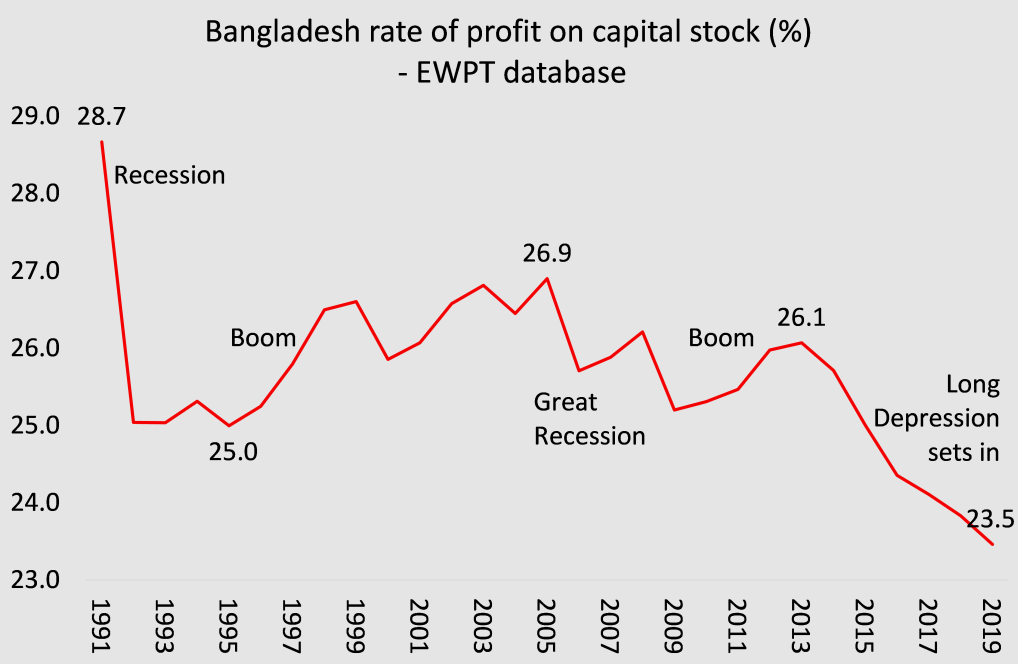

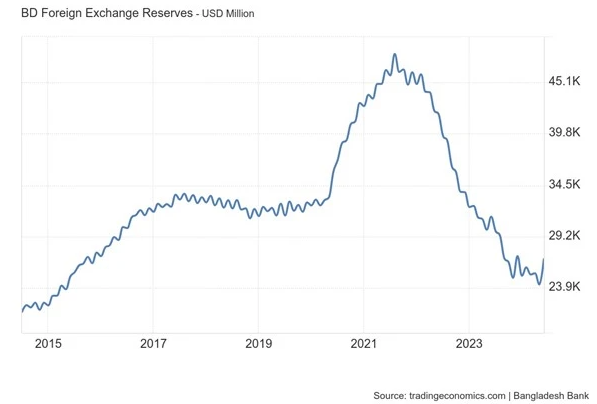

Capitalism’s crises are thus undermining the capitalist establishment, driving political polarization to the right and the left, and intensifying external conflicts between states at every level of the imperialist hierarchy. Rivalries between established and rising powers, most obviously the U.S. and China, are growing, so are conflicts between them and regional powers, and these conflicts are often over control of oppressed nations like Palestine, Ukraine, and Taiwan.

Within nation-states, the establishment’s parties and regimes are unable to address the grievances of the classes beneath them. That has opened the door to their opponents, most commonly the far right and its parties. But if and when those forces come to power, they have been unable to impose stable regimes, because they can neither solve capitalism’s crises nor its growing inequality. Their policies, in fact, exacerbate them.

In the rare cases where leftist and reformist parties like Syriza in Greece have managed to win governmental power, they too find themselves constrained by the capitalist state and economy, unable to deliver and forced into compromises. Disappointment with their rule, in turn, has then re-opened the door to the capitalist establishment and far right to regain power.

The failure of governments to deliver any kind of solution has triggered revolts from below by both the working class and the oppressed as well as the deranged petty bourgeoisie. But the revolutionary Left is at this point too small and not implanted enough to galvanize mass struggles for reform and a challenge to the system, enabling the establishment and right to co-opt and channel movements into their electoral projects or simply repress them with the utmost brutality.

A socialist approach to electoral politics

In this epoch of political instability, socialists must develop a strategic approach to elections. We are not anarchists; we do not dismiss elections as irrelevant to the class struggle. Electoral politics are one of the battlefields of the class struggle.

We must contest our rulers on all fronts of the system from the economic to the social, ideological, and political. We cannot ignore or abstain from engaging in battle on any of those fronts. If we leave electoral politics to only the capitalist and far right forces that only empowers them to have more influence over the politics, ideology, and organizational priorities of workers and oppressed groups. We ignore elections at our peril.

That’s why Engels argued that workers everywhere must form a political party of their own to lead the struggle on all fronts of the class war, including contesting our rulers’ parties in elections. Elections are a means to win the political, ideological, and organizational independence of our class from our rulers and a way, if used properly, to agitate for struggle from below for radical reforms on the road to the revolutionary transformation of society.

In the U.S., we have an exceptional political system. Unlike most countries, we have no social democratic or labor party, but instead have two parties of the capitalist class, the Democrats and Republicans. Both are funded and controlled by the capitalist class and used to advance their interests, not ours.

However, the parties are not the same, and since the 1930s, they have operated in different fashions. The Republicans have been the main party of capital–its A-Team. The Democrats have been the B-Team, which has come off the bench when the A-Team has failed, to promise liberal reforms to preserve the system and head off the formation of an independent party of workers and the oppressed. They exist to co-opt the Left and neutralize class and social struggle.

The transformation of Washington’s two-party system

Up until the Great Recession, the two parties have shared a commitment to neoliberalism at home and imperial hegemony abroad, and differences between them have been of degree not of kind. But in today’s epoch of crisis, this political setup has been radically altered.

Trump, a lumpen capitalist outsider to the two parties, has transformed the GOP into a far-right party similar to that of Marine Le Pen’s National Rally in France. It has found an electoral base among small business owners and disorganized, impoverished, alienated sections of the working class, especially but not exclusively white workers hammered by deindustrialization and neoliberalism.

Today’s Trumpite Republican Party advocates authoritarian nationalist solutions to the real crises of capitalism. Their program is embodied in Project 2025. While disavowed by Trump, his brain trust designed it and his Vice Presidential nominee, the execrable “shillbilly” J. D. Vance, wrote the forward to the new book by Kevin Roberts of the Heritage Foundation, which commissioned it. And most of the ideas from the Project ended up as bullet points in the GOP’s platform emphasized in classic Trumpite style with bold headers and capital letters.

Project 2025 advocates an American-first nationalist foreign policy opposed to Washington’s multilateral alliances like NATO; massive increases in protectionist tariffs, radical deregulation and tax cuts for the rich; the dismantling of the so-called administrative state; and the declaration of a culture war on oppressed groups, especially people of color, women, queer people, and migrants. It reflects the interests of a narrow band of middling venture capitalists in the tech sector, especially in Crypto and AI, nationally-oriented corporations, and the resentful bigotry of small business owners and downwardly mobile professionals.

Under Biden, the Democratic Party has replaced the GOP as the main party of capital. It has the bulk of capitalist backing and has forged an electoral base in upper sections of the professional middle class and much of the unionized working class.

Biden developed a strategy of imperialist Keynesianism to accomplish several interrelated goals. He has sought to refurbish U.S. alliances against China and Russia, implement an industrial policy to rebuild U.S. manufacturing (especially in high tech to compete with China) and offer a program of liberal reforms to restore capitalist hegemony over the popular classes, head off the challenge from the far right GOP, and co-opt and neutralize social democrats like Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio Cortez within the Democratic Party.

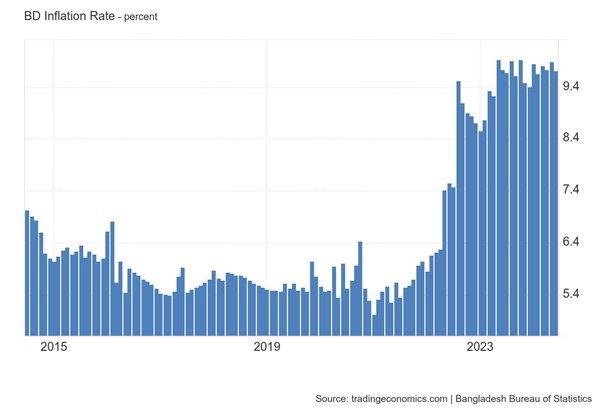

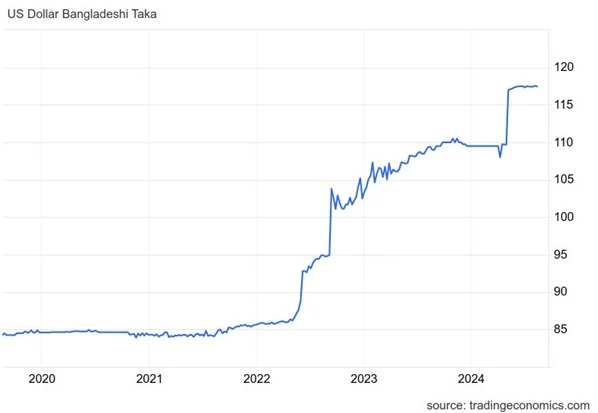

Biden’s program however has proved completely inadequate to address the growing grievances among the working classes and oppressed, who have been hammered by inflation. It has also failed to overcome the system’s metastasizing crises, especially climate change, which is causing catastrophe after catastrophe with insufferable heat waves, floods, wildfires, and storms wreaking havoc from California to Vermont.

Even worse, his project of reasserting U.S. imperial hegemony, in particular by supporting Israel in its genocidal war on Palestine, has driven Palestinians, Arabs, Muslims, Black people, and multiracial youth to oppose his administration. They all see him not as some liberal, or as Sanders persists in calling him “the most progressive president since FDR,” but as a war criminal rightly deserving the moniker, Genocide Joe.

Biden’s unrelenting support for Israel combined with the mass movement in solidarity with Palestine undermined his self-serving propaganda about Washington being a protector of a so-called international rules-based order. It also doomed his chances of reelection with hundreds of thousands in battleground states joining the “Uncommitted Movement” in the Democratic Party’s primaries, including the pivotal battleground state of Michigan.

His policies, his mental incapacity demonstrated in his catastrophic debate with Trump, and his war crimes drove down his approval ratings and depressed, alienated, and enraged the very electoral base he needed for reelection. That enabled Trump, the other widely-despised candidate, to stretch his lead over Biden and appear to be set to win the presidential election and even sweep the Republicans back into control of both houses of Congress.

Harris and the resurrection of the Democratic Party establishment

The Democratic coronation of Harris has transformed this election almost overnight. They replaced a faltering candidate with a competent one and are promoting her as a Black, South Asian Woman to re-galvanize capitalist donors, party activists, and what had been a demoralized electoral base.

There is real enthusiasm for her and a sense that she could now win. Her popularity is an echo of the appeal that Obama used to become the country’s first Black president. Capitalists and small donors have reopened their spigots of contributions, pouring $310 million into Harris’ campaign in July. She has hosted mass phone calls of party activists and staged rallies with large raucous crowds.

Harris has also benefited from the bumbling rollout of the Trump/Vance ticket after the GOP’s Convention. Trump clearly misses Biden as his former defenseless opponent and has been unable to come up with anything but racist and misogynist attacks against Harris, which may consolidate his right-wing base but will likely lose him support among suburban swing voters.

For his part, Vance has proved himself little better in stump speeches than the repugnant charisma vacuum Ron DeSantis. He’s been trapped trying to justify misogynist attacks against Democratic Party women as “childless cat ladies” and explain away his catalog of old denunciations of his boss, Donald Trump. No doubt, Trump regrets choosing this apprentice and could conceivably fire him in a fit of anger.

We should be clear, however, that Harris has only changed the atmospherics of the campaign, not the class nature of the Democratic party or its imperialist Keynesian program. As The New York Times notes, she has rejected the Left, embraced the establishment, and positioned herself as a competent defender of Biden’s record.

In a sign of just how far to the right she has moved, Harris now boasts about her career as a “tough on crime” prosecutor and, in an effort to fend off Republican attacks, promises to enact extreme border restrictions if elected. What crumbs she does offer workers and the oppressed are recycled from Biden’s Build Back Better that Congress torpedoed and would likely do so again in the future.

Even if enacted, however, those mild reforms will not address the deep grievances of the working class and oppressed. That includes her promise to fight for abortion rights. At best, the Democrats would restore the status quo ante, when Roe was the law of the land.

At worst, as they have done before, they will use their pro-choice position to galvanize electoral support, but when faced with intransigent Republican opposition, abandon their promise for national re-legalization. And of course, they will not fight to restore public funding of abortion.

Real change on that and every other demand must be fought for from below. Nowhere is this more clear than on Palestine. While she has voiced sympathy with Palestinians being massacred in Gaza and called for a ceasefire, she never opposed Biden’s unconditional support, funding, and arming of Israel to carry out the genocide.

In fact, she has supported it hook, line, and sinker. As Vice President, she has been an accomplice in the genocide. And, as the nominee in waiting, she has reiterated her support for Israel’s so-called right to self-defense (something an occupier does not have under international law) and condemned protests by solidarity activists.

The dead end of lesser-evilism

That said, we must be crystal clear: The two candidates and parties are not the same and it is an ultra-left mistake to characterize them that way. The greater evil is obviously Trump and the far right GOP. He, not Harris, is threatening the deportation of 13 million human beings and the criminalization of queer people.

Harris and the Democratic Party are lesser evils by comparison. But that does not exonerate them of being evil. Their support for Israel, record increases in fossil fuel production, and mass repression at the border prove that beyond a shadow of a doubt.

Both candidates and parties are evil, but in different ways. Trump and the GOP are open enemies of unions and oppressed groups, despite their hosting turncoat Sean O’Brien, president of the Teamsters Union, and this-or-that speaker or influencer of color at their Convention.

Harris and the Democrats are a capitalist party that advances that class’s interests by co-opting and neutralizing the Left and class and social struggles. They channel those back into the confines of capitalist liberalism and tinkering with the system, a tinkering that is totally inadequate to meet the needs of the vast majority.

The so-called pragmatic Left contends that supporting the lesser evil is the only realistic way to stop the greater evil, gain breathing space for our side to build its forces, and over time build a political alternative. In fact, the last four years have decisively disproved each of these contentions.

Most obviously, supporting the lesser evil has not stopped the rise of the right in the US. Even after all the convictions for January 6, Trump and the GOP not only survived, but have expanded their forces and enlarged their base.

Because the Left, social movements, and unions abandoned opposition to Biden and the Democrats, and stopped, on the whole, fighting for our more radical demands, Trump and the GOP now pose as the only opposition. As a result, Trump at this point leads in national polls and in the electoral college’s battleground states.

The toll of the last four years on the Left, social movements, and unions has been extreme. Once our side threw support behind Biden and the Democrats in 2020, they, at best, implemented their program, not ours, and, at worst, adapted to the right.

As a result, four years later, the Left, social movements, and unions are in the main weaker, more disorganized, and less confident. The only exceptions to this norm are unions like the UAW that have organized and struck against their bosses and the Palestine solidarity movement, which galvanized popular opinion against Israel’s genocidal war, helped drive Biden to abandon his campaign, and secured important victories on campuses across the country.

The Left, social movements, and unions should draw the lessons from the last four years. Implacable agitation and struggle for our demands is what wins, not taking off our marching boots, putting away our picket signs, abandoning the battlefield, and supporting the lesser evil in the vain hope of stopping the greater one. That is the road to certain defeat in the short term and long term.

Socialists and the 2024 elections

Regardless of the outcome of this election, we are headed for political paralysis in D.C. and a looming constitutional crisis. Even with the sugar rush after Harris’s coronation as the Democrats’ nominee, the election is at best a dead heat with three months to go. The result will be determined, not by the popular vote, but by seven battleground states that will tip the undemocratic Electoral College to one of the two candidates.

It could go either way in the presidential contest, depending on twists and turns in the campaigns and unpredictable events in the country and world. In the congressional elections, the two parties will narrowly divide up the vote, ushering a weak one-party government or a divided one. Either way, the slim majorities and a weak mandate will most likely produce political paralysis.

If Trump wins, he will try to implement his program of authoritarian nationalism with the approval of the far-right majority in the Supreme Court. Democrats in Congress and in the states they control will oppose Trump’s most extreme measures like mass deportation or criminalization of queers, including refusing to obey his orders. That would open up a constitutional crisis.

If Harris wins, Trump will not accept the result, not only because he does not believe in democracy but also because he faces certain prosecution and likely conviction on several felony charges. Under threat of imprisonment, he will encourage his deranged, faithful base of far-right militants to stage protests including violent ones like we witnessed on January 6. Already neo-Nazis are marching in many cities like Nashville.

The GOP will follow him in opposing anything and everything Harris proposes both at the federal and state level, and the Supreme Court will support their efforts. Thus, even in the case of a Harris victory, we will be subject to political paralysis and a constitutional crisis.

Faced with this bleak scenario, what should the Left do? First of all, we should not argue with individuals about what they do at the ballot box. That is not the key question and debate to have. Instead, we must argue that activists, social movements, and unions should not spend our time, money, and energy campaigning for Harris as the lesser evil.

Those resources should be spent on building independent social and class struggles for our demands. Imagine what we could do with the $310 million Harris raised in July. Imagine what we could do with the thousands of volunteer hours spent on getting her elected. Imagine the organizations and unions that could be built, the strike funds bolstered, and the strikes and mass protests staged.

In making this strategic argument, we should not treat our siblings on the Left and in unions and movements who disagree with us as opponents to be denounced and dismissed. We should debate instead with them as our comrades in a common struggle. That is crucial because we will need to unite and fight together on the other side of this election against the right and the capitalist establishment.

And we should find points of agreement over the next three months, most importantly the demands that we support together. We should encourage them to join us in agitating for reforms like Medicare for All, a Green New Deal, Legalization for All, a Permanent Ceasefire to Israel’s genocidal war, and the immediate end to all U.S. aid to Israel, among many others.

In unions and movements, we should emphasize that we should not support Harris and the Democrats if they do not support our demands. This is especially true for the Palestine solidarity movement and our demand for an end to the war and all U.S. aid to Israel. As Noura Erakat, recently wrote about Harris, “Endorsing her without exacting this very basic concession is strategically short-sighted and self-defeating.”

Fundamentally, we have to argue for the political and organizational independence of our movements and unions from the Democratic Party. Our independent class and social struggles are the key to winning any immediate victories against the opposition of both parties, charting a way through their looming constitutional crisis, and building a new socialist party to lead the revolutionary transformation of the failing capitalist system.

Ashley Smith is a member of the Tempest Collective in Burlington, Vermont. He has written in numerous publications including Spectre, Truthout, Jacobin, New Politics, and many other online and print publications.