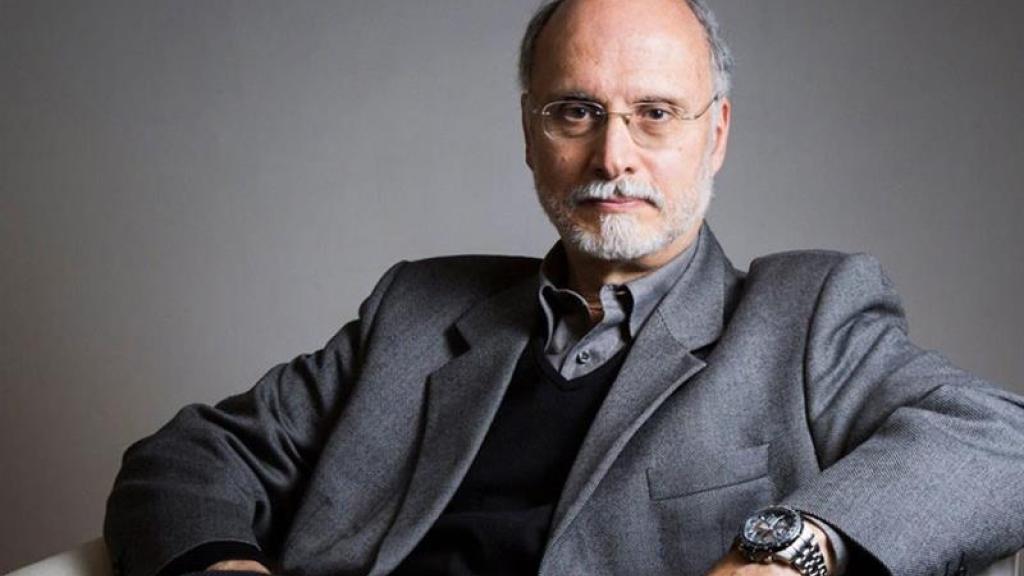

‘Political struggle against Putin’s regime is the best way to stop his war machine’: An interview with Russian oppositionist Ilya Yashin

First published in Catalan at Ara. Translation by Dick Nichols for LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal

Ilya Yashin is a Russian opposition politician who was released from prison on August 1, in the prisoner exchange between Russia and the United States. Since his exile in Germany, he has been touring several European cities to reach out to the Russian diaspora, which has taken him to Barcelona. Yashin, now 41, was jailed in 2022 for criticising the invasion of Ukraine on his YouTube show. He was sentenced to eight and a half years in prison for denouncing the Bucha massacre. He is now free thanks to the largest prisoner exchange of the Cold War, in which sixteen Russian political prisoners and US citizens Evan Gershkovitx and Paul Whelan were exchanged for prisoners in the West claimed by Russia, including Spain’s Pablo Gonzalez, accused of espionage, and Vadim Krasikov, who shot a man in the head to death in a Berlin park on Moscow's orders.

What is the life of a Russian oppositionist in prison like?

I spent twenty-five months there. I had prepared myself mentally, because from the first day of the Ukrainian war I knew that if I did not leave Russia (and I was not willing) I would end up behind bars. Every day I woke up thinking, “If they don't arrest me today, it will be tomorrow.” And it was in the fourth month of the war.

Prison is very hard physically and psychologically, because it is designed to subdue you, to break you as a person. It is very easy to lose a part of your humanity, because the environment is very aggressive. But if you endure the psychological pressure, it can also become a place of personal and even spiritual growth. Ironically, I think my time in prison has made me more flexible. And I have learned to coexist with people who do not think like me, to coexist peacefully and reach agreements. And I think that understanding will be useful to me now.

Is there talk of war in Russian prisons?

Prisoners have become a key human resource for Putin’s war. Many prisoners end up agreeing to go to war, because especially if they have long sentences it is the only chance to get out of it. Almost every prisoner I was with knew someone who had gone to Ukraine. But the important thing is that they do not see it as a just, patriotic or noble war. They see it only as a source of money or a way to shorten the sentence.

You were released in the exchange, but you had always said that you did not want to leave Russia. How do you experience the fact that other opponents are still behind bars?

These are very contradictory emotions. Obviously, I am happy to be free: only two months ago I was handcuffed and in a cell with poor food and I could only communicate with criminals or officials. Now I am free, I can talk to you. And I can hug my mother every time she comes to visit me.

But at the same time I feel very guilty, because I cannot help thinking that my place on the plane that took us out of Russia had to go to someone else. In fact, I asked not to be exchanged because my political position was fully conscious. I am a Russian political activist and I was still a political activist in prison. I never considered leaving the country and I did not do it of my own free will. In fact, I was deported.

And I see that many others are still in prison in danger of losing their lives. Aleksei Gorinov [former Russian councillor imprisoned for criticising the war] is missing a lung and could die at any moment. Maria Ponomarenko, a journalist serving time for reporting on the war, is tortured and on the verge of suicide. Igor Baryshnikov [also an anti-war activist] has a tumour. While I am at liberty, they are still rotting in prison and their lives are in danger.

Can there be political change in Russia with a population paralysed by fear?

Historical change in Russia is inevitable and Putin’s regime is holding it back. It is holding it back with the use of force, but this will not last forever. Very serious internal contradictions are accumulating in Russia. What united people during these years was Putin’s promise of stability after the difficult reform era of the 1990s. Putin promised people tranquillity and prosperity. And now it is all over. People feel threatened, the country is becoming more and more isolated. The war in Ukraine has taken away the most important thing anyone can have: hope for the future. That is what Putin has taken away from us.

Today Russia is in a very painful situation, where it is desperately searching for its identity. The feeling is that everyone hates everyone else. People are constantly arguing. And these accumulated contradictions will eventually explode. The debate that will begin in Russia after the end of the war will determine where the country will go.

What impact did Navalny’s death have on the Russian people, on the opposition and on yourself?

Navalny was not just a politician. Just like Boris Nemtstov [Russian opposition politician who was assassinated in 2015], Navalny was a figure of systemic importance, around whom coalitions were formed and projects were built. It was a very serious loss for Russian society, because especially people of my generation associated their future with Navalny. When they killed him, they killed hope. No one will be able to take his place.

I believe that the vacuum he has left can only be filled by collective action. The Russian opposition has always been built around a great figure and I think we must now replace him with solidarity at the most basic level. If we succeed we will have a chance.

Alexei Navalny was a friend of mine

What role do you think you can play in that change?

One of the problems we have is the atomisation of Russian society in general and also of the people who defend the values of freedom, humanism and democracy. By my example I want to show that we can participate in politics in a different way.

That is why I do events and debates on social networks. I want to show that we can talk to each other in a correct and respectful way and that we can find common ground for the future. This is the goal of my tour of European cities to meet compatriots who had to leave Russia because of the war, because of Putin's dictatorship. I also do streaming programs to address people who have stayed in Russia.

When you denounced the massacre committed by the Russian army in the Ukrainian town of Bucha, you knew you would end up in prison. Why did you do it?

Bucha was the excuse to arrest me. I was imprisoned for not keeping quiet and for telling people the truth about the war, the truth about what happened in Bucha and many other war crimes that Putin’s army was committing in Ukraine. I knew it would land me in jail, but I could not keep quiet. I think it was very important for a Russian politician to tell the truth about the war.

Do you think the Russian opposition should support Ukraine in the war?

There are different points of view, and this does not worry me. Some think that it is necessary to collect money for the Ukrainian army and give them moral and political support; others collect aid for refugees; others defend Ukrainian prisoners of war in Russian courts.

I think, like others, that political struggle against Putin’s regime is the best way to stop his war machine. I do not participate in fundraising for the Ukrainian army and consider that my role should be to change public opinion inside Russia.

What do you say to the Ukrainian offensive in Kursk?

It pains me that the war has come to my country, but I warned from the first days that Putin would not have it easy in Ukraine and that the war would eventually come to Russian territory. I am not happy, but I understand the logic of the Ukrainian leadership: they do not want Russian land, but have made this offensive as a form of self-defence. They entered the Kursk region to strengthen their bargaining power.

What is needed is for all Russian troops to withdraw from Ukraine. And when this has happened there will be no Ukrainian soldiers left on Russian territory. We must do everything possible to achieve this.

You met Pablo Gonzalez, the Spaniard accused of espionage in Poland who was also released in the exchange and received by Putin in Moscow. What do you think of his case?

Russia had recognised Pavel Rubtsov [his real name] as a spy at the time it exchanged him. Putin met him at the foot of the plane to shake his hand and he was wearing a T-shirt that said “The Empire Needs You”. The fact that he was put on an exchange list with other spies, with Krasikov, although many other Russian spies have been left behind in Western prisons, closes the debate.

I have no doubt that Pavel Gonzalez is a Russian intelligence officer. I know that he worked against the Boris Nemtsov Foundation, which is run by his daughter Zhanna Nemtsova, and that he stole documents from her computer. But in my case it did not hurt. In fact, it made me smile to think how uselessly the Russian secret services spend money.

I spent quite a lot of time with Pablo: whenever he came to Spain we used to meet and the last time I was in Barcelona, five years ago, he showed me around the city. I do not quite understand what the point of his work was: it seems that he was doing a psychological profile of me, but I have always been a public figure, I know that I am under the magnifying glass and I have nothing to hide. I think that when he met me he was convinced that I am not an extremist or a criminal. I guess that is the information he sent to Moscow.

He did not harm me, but the truth is that he pretended to be a journalist when in fact he was an agent gathering information. I must also say that I am glad he was put on the exchange list, because that allowed the release of real Russian journalists and activists, such as Vladimir Karamurza, Aleksandra Skotchilenko, Lilia Chanixeva or Ksenia Fadeeva. The release of Gonzalez for me is less painful than that of Krasikov, who was a murderer