In an aged care home in Roth, not far from the Bavarian city of Nuremberg, Ilse introduced herself as the daughter of a Nazi. It's a fact she never concealed. She said her father could not stand Nazi leaders Heinrich Himmler, and that he didn't like Hermann Göring or Joseph Goebbels either.

"Because only money counted for them," Ilse said, adding that "daddy" thought of the nation.

Ilse's father, Erich Julius Eberhard von Zelewski, was born on March 1, 1899, in what is now in the Polish town of Lebork, near Gdansk. Soon German nationalism cast its spell on the young von Zelewski. Three months after the outbreak of World War I, he joined the German Reich army and was awarded the Iron Cross after a year of service. At the age of 18, he was promoted to lieutenant.

In 1930, having since acquired the double name of von dem Bach-Zelewski, he became a member of the Nazi party (NSDAP) and joined the SS one year later. In 1932, already an SS Obersturmführer, he became a Reichstag delegate.

Ilse von dem Bach: 'Daddy was an honorable man'

In November 1939, von dem Bach-Zelewski, who was regarded by his superiors as a "very good National Socialist, loyal and honest, very impulsive," was given a new task: He was to Germanize the Poles in what was then Silesia. In the summer of 1941, he organized the mass executions of Jews in Belarus as an SS and police commander. Later he led the

fight against the partisans, which also claimed countless civilian victims.

Playing cards with his uncle

In the summer of 1944, 7-year-old Stanislaw Maciej Kicman, affectionately known as Macius, was sitting at a table eating lunch with his mother, father and grandmother.

"The soldiers came to take my father to the army," he said recently. "They showed him a letter and my father said, 'I'm coming.' He left his soup and said goodbye. He hid a gun under his coat. My mother asked: 'Czesiu, when will I see you?' He said: 'It will be over soon. In a week.'"

Macius did not know where his father was going. "Papa is going to your uncle's. Maybe they play cards. Maybe Papa will lose," his mother explained. "Papa always wins," Kicman replied. His father "played cards" for almost a year. That's how long the war lasted. And he won.

Later, Kicman's mother wrote of the return of her husband: "I took off my coat in the hall. Suddenly, the sight of a hand with a hat took my breath away. Macius screamed with delight: 'Papa, papa, my papa.' I leaned my head against the wall. Thank God."

Kicman as a child with his family

'Close your eyes, it doesn't hurt'

Willy Fiedler served in the Wehrmacht. In the early days of the Warsaw Uprising, when the Polish underground army rose up in the capital against the German occupiers, he witnessed an execution in Pfeifer's tannery. He saw people forced to lie down before being shot. About 2,000 people died in the tannery. The executions went on for weeks.

Fiedler saw only a part of the killings. He didn't know about Hitler's order: Warsaw was to be razed to the ground. The soldiers of the Dirlewanger Regiment, notorious for their cruelty, received the order on August 5, 1944. At 7 a.m. they began an attack on the Wola district. The SS exterminated the civilian population. Historians have estimated that between 20,000 and 45,000 people died that day. On August 6 there were more mass executions. It was one of the worst massacres of World War II.

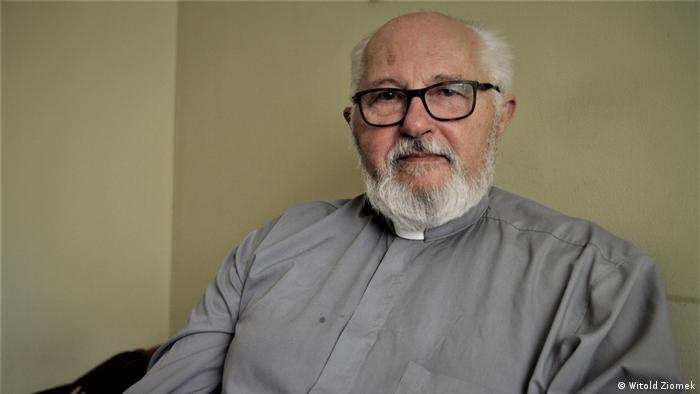

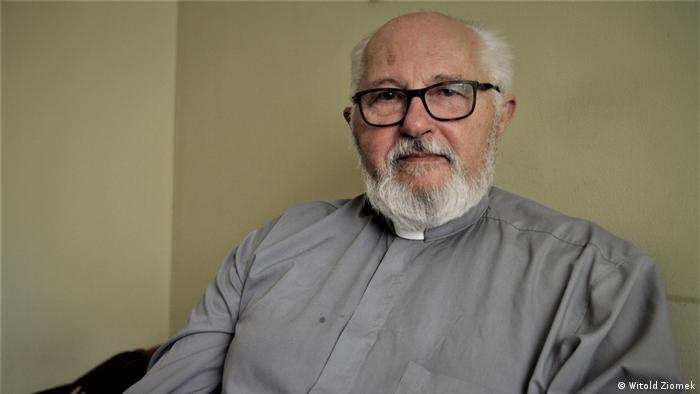

Stanislaw Maciej Kicman, who is now a pastor, said he remembers Nazis rushing into his house and pushing him and his mother to a church. They ordered them to kneel down and pointed guns at them.

"I was aware of my imminent death. I snuggled up against my mother," said Kicman. "My mother hugged me and said, 'Close your eyes, it doesn't hurt.'"

The gun jammed. Kicman and his mother were lucky and escaped with their lives.

Stanisław Maciej Kicman did not know where his father went during the war

'That son of a bitch!'

When asked by the Nuremberg prosecutor Jerzy Sawicki when he had arrived in the Polish capital, Erich von dem Bach — he had dropped the Polish-sounding surname Zelewski in 1940 — said, "It was two weeks after the outbreak of the uprising." He answered as a key witness for the prosecution, not as a defendant.

The Nuremberg Trials begin on November 20, 1945. Historical sources show that in exchange for his testimony, the Americans, to whom he had given himself up in August 1945, did not hand von dem Bach over to the Poles or the Soviet Union.

Once a month, Ilse traveled with her mother to Nuremberg to see her father. She did not read newspaper reports. "I wanted to shield myself from them," she said.

Von dem Bach's testimony heavily incriminated his comrades. Göring, who was later sentenced to death for crimes against humanity, among other charges, reacted indignantly, calling von dem Bach a "traitor, "bastard" and "the bloodiest murderer in this whole system."

Unlike Göring and Hess, right, von dem Bach-Zelewski was at the Nuremberg trials as a witness, not as a criminal

'Yes, women and children too'

Von dem Bach wanted to save himself: "I told the commanders that civilians should be treated according to the Geneva Convention."

"In the cemetery, I saw how a group of civilians ... was shot by members of the Heinz Reinefarth's combat group. I pointed out to him that his troops were shooting innocent civilians. ... He said that he had received an explicit order not to take prisoners and to kill every inhabitant of Warsaw. I asked: 'Women and children too?' To which he replied: 'Yes, women and children too.'"

With this testimony, he betrayed himself. Von dem Bach had claimed that he had only come to Warsaw on August 13, after the most terrible massacres. The group commanded by SS-General Heinz Reinefarth did indeed kill about 1,500 people near the cemetery, but that was on August 6.

Everything indicates von dem Bach was in Warsaw that day and

knew about the extent of the mass murders. Von dem Bach never had to answer for this crime. Neither did Reinefarth, who made a career for himself after the war in the state of Schleswig-Holstein as a mayor and member of the state parliament.

'Hitler's man to the end'

After the war, von dem Bach-Zelewski tacked the Polish component back onto his name. He was not charged in the Nuremberg Trials, though he was put under house arrest. Later, he worked as a night watchman. In 1961, he was sentenced to four and a half years in prison for ordering the murder of the SS officer Anton von Hohberg und Buchwald. A year later, he received a second sentence because of more murders in the 1930s. This time, he was sentenced to life imprisonment.

The German news magazine Der Spiegel reported in 1961 that "when he was asked by the judges how he reconciled the ethos of a former Prussian lieutenant … with helping Hitler's SS, the defendant went on record as saying: 'I was Hitler's man to the end. I am still convinced of his innocence."

Von dem Bach-Zelewski said he was 'Hitler's man to the end'

His children were in the courtroom that time, too.

"I wanted to support my father, give him some security. I was terribly angry that everyone was saying we should be ashamed of him. I was never ashamed," Isle said.

She said she still remembers their time together, but she does not like talking about her feelings.

"He always called me Ila. I loved him very much," she said. "Whatever I asked him, he always knew the answer. He was well-read in history, had a sense of humor and was a good story-teller."

Writing to his wife and daughter from prison, von dem Bach-Zelewski admitted to making many mistakes and that he had difficulty being a "witness of the truth" against those who he called his own people and knowing that "Germany would be scorned for generations."

On March 8, 1972, von dem Bach-Zelewski died in prison, and his daughter said she still misses him. "Daddy was an honorable man," the 85-year-old said.