How the Modern Workplace Fails Women

The world of work needs a wholesale redesign — led by data on female bodies and female lives

Caroline Criado Perez

Follow

Dec 24, 2019 · 11 min read

Illustration: solarseven/Getty Images

Invisible Women by Caroline Criado Perez (Abrams Press) was the winner of the 2019 Financial Times and McKinsey Business Book of the Year Award. In this excerpt from the book, the author describes some of the many ways in which women are harmed by workplaces designed without their needs in mind.

Itwas in 2008 that the big bisphenol A (BPA) scare got serious. Since the 1950s, this synthetic chemical had been used in the production of clear, durable plastics, and it was to be found in millions of consumer items from baby bottles to food cans to main water pipes. By 2008, 2.7 million tons of BPA was being produced globally every year, and it was so ubiquitous that it had been detected in the urine of 93% of Americans over the age of six. And then a U.S. federal health agency came out and said that this compound that we were all interacting with on a daily basis may cause cancer, chromosomal abnormalities, brain and behavioral abnormalities, and metabolic disorders. Crucially, it could cause all these medical problems at levels below the regulatory standard for exposure. Naturally, all hell broke loose.

Itwas in 2008 that the big bisphenol A (BPA) scare got serious. Since the 1950s, this synthetic chemical had been used in the production of clear, durable plastics, and it was to be found in millions of consumer items from baby bottles to food cans to main water pipes. By 2008, 2.7 million tons of BPA was being produced globally every year, and it was so ubiquitous that it had been detected in the urine of 93% of Americans over the age of six. And then a U.S. federal health agency came out and said that this compound that we were all interacting with on a daily basis may cause cancer, chromosomal abnormalities, brain and behavioral abnormalities, and metabolic disorders. Crucially, it could cause all these medical problems at levels below the regulatory standard for exposure. Naturally, all hell broke loose.

Fearing a major consumer boycott, most baby-bottle manufacturers voluntarily removed BPA from their products, and while the official U.S. line on BPA is that it is not toxic, the EU and Canada are on their way to banning its use altogether. But the legislation that we have exclusively concerns consumers: no regulatory standard has ever been set for workplace exposure.

The story of BPA is about gender and class, and a cautionary tale about what happens when we ignore female medical health data. We have known that BPA can mimic the female hormone estrogen since the mid-1930s. And since at least the 1970s we have known that synthetic estrogen can be carcinogenic in women. But BPA carried on being used in hundreds of thousands of tons of consumer plastics, in CDs, DVDs, water and baby bottles, and laboratory and hospital equipment.

“It was ironic to me,” says occupational health researcher Jim Brophy, “that all this talk about the danger for pregnant women and women who had just given birth never extended to the women who were producing these bottles. Those women whose exposures far exceeded anything that you would have in the general environment. There was no talk about the pregnant worker who is on the machine that’s producing this thing.”

This is a mistake, says Brophy. Worker health should be a public health priority if only because “workers are acting as a canary for society as a whole. If we cared enough to look at what’s going on in the health of workers that use these substances every day,” it would have a “tremendous effect on these substances being allowed to enter into the mainstream commerce.”

But we don’t care enough. In Canada, where women’s health researcher Anne Rochon Ford is based, five women’s health research centers that had been operating since the 1990s, including Ford’s own, had their funding cut in 2013. It’s a similar story in the U.K., where “public research budgets have been decimated,” says Rory O’Neill. And so the “far better resourced” chemicals industry and its offshoots have successfully resisted regulation for years, dismissing studies and other evidence of the negative health impacts of their products.

The result is that workplaces remain unsafe. Brophy tells me that the ventilation he found in most auto-plastics factories was limited to “fans in the ceiling. So the fumes literally pass the breathing zone and head to the roof and in the summertime when it’s really hot in there and the fumes become visible, they will open the doors.” It’s the same story in Canadian nail salons, says Rochon Ford. There are no ventilation requirements, there are no training requirements. There is no legislation around wearing gloves and masks. And there is nobody following up on the requirements that do exist — unless someone makes a complaint.

The introduction of Big Data into a world full of gender data gaps can magnify and accelerate already-existing discriminations.

But who will make a complaint? Certainly not the women themselves. Women working in nail salons, in auto-plastics factories, in a vast range of hazardous workplaces, are poor, working class, often immigrants who can’t afford to put their immigration status at risk. And this makes them ripe for exploitation.

Auto-plastics factories tend not to be part of the big car companies like Ford. They are usually arms-length suppliers, “who tend to be nonunionized and tend to be able to get away with more employment-standard violations,” Rochon Ford tells me. Workers know that if they demand better protections the response will be “Fine, you’re out of here. There’s 10 women outside the door who want your job.” “We’ve heard factory workers tell us this in the exact same words,” says Rochon Ford.

If this sounds illegal, well, it may be. Employee rights vary from country to country, but they tend to include a right to paid sick and maternity leave, a right to a set number of hours, and protection from unfair and/or sudden dismissal. But these rights only apply if you are an employee. And, increasingly, many workers are not.

In many nail salons, technicians are technically independent contractors. This makes life much easier for the employers: the inherent risk of running a company based on consumer demand is passed on to workers, who have no guaranteed hours and no job security. Not enough customers today? Don’t come in and don’t get paid. Minor accident? You’re out of here, and forget about redundancy pay.

Nail salons are the tip of an extremely poorly regulated iceberg when it comes to employers exploiting loopholes in employment law. Zero-hour contracts, short-term contracts, employment through an agency, are all part of the Silicon Valley-built “gig economy.” But the gig economy is in fact often no more than a way for employers to get around basic employee rights. Casual contracts create a vicious cycle: the rights are weaker to begin with, which makes workers reticent to fight for the ones they do still have. And so those get bent too.

Naturally, the impact of what the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) has termed the “startling growth” of precarious work has barely been gender-analyzed. The ITUC reports that its feminized impact is “poorly reflected in official statistic and government policies,” because the “standard indicators and data used to measure developments on labor markets” are not gender-sensitive, and, as ever, data is often not sex-disaggregated, “making it sometimes difficult to measure the overall numbers of women.” There are, as a result, “no global figures related to the number of women in precarious work.”

But the regional and sector-specific studies that do exist suggest “an overrepresentation of women” in precarious jobs. A Harvard study on the rise of “alternative work” in America between 2005 and 2015 found that the percentage of women in such work “more than doubled,” meaning that “women are now more likely than men to be employed in an alternative work arrangement.”

This is a problem because while precarious work isn’t ideal for any worker, it can have a particularly severe impact on women. For a start, it is possible that it is exacerbating the gender pay gap: in the U.K. there is a 34% hourly pay penalty for workers on zero-hours contracts, a 39% hourly pay penalty for workers on casual contracts, and a 20% pay penalty for agency workers — which are on the increase as public services continue to be outsourced. But no one seems interested in finding out how this might be affecting women.

There is, to begin with, “limited scope for collective bargaining” in agency jobs. This is a problem for all workers, but can be especially problematic for women because evidence suggests that collective bargaining (as opposed to individual salary negotiation) could be particularly important for women. As a result, an increase in jobs like agency work that don’t allow for collective bargaining might be detrimental to attempts to close the gender pay gap.

But the negative impact of precarious work on women isn’t just about unintended side effects. It’s also about the weaker rights that are intrinsic to the gig economy. In the U.K., a female employee is only entitled to maternity leave if she is actually an employee. If she’s a “worker,” that is, someone on a short-term or zero-hours contract, she isn’t entitled to any leave at all, meaning she would have to quit her job and reapply after she’s given birth.

Another major problem with precarious work that disproportionately impacts female workers is unpredictable, last-minute scheduling. Women still do the vast majority of the world’s unpaid care work and, particularly when it comes to childcare, this makes irregular hours extremely difficult. The scheduling issue is being made worse by gender-insensitive algorithms. A growing number of companies use “just-in-time” scheduling software, which use sales patterns and other data to predict how many workers will be needed at any one time. They also respond to real-time sales analyses, telling managers to send workers home when consumer demand is slow.

It’s a system that works great for the companies that use the software to boost profits by shifting the risks of doing business onto their workers, and the increasing number of managers who are compensated on the efficiency of their staffing. It feels less great, however, for the workers themselves, particularly those with caring responsibilities. The introduction of Big Data into a world full of gender data gaps can magnify and accelerate already-existing discriminations: whether its designers didn’t know or didn’t care about the data on women’s unpaid caring responsibilities, the software has clearly been designed without reference to them.

The work that (mainly) women do (mainly) unpaid, alongside their paid employment is not an optional extra. This is work that society needs to get done. And getting it done is entirely incompatible with just-in-time scheduling designed entirely without reference to it. Which leaves us with two options: either states provide free, publicly funded alternatives to women’s unpaid work, or they put an end to just-in-time scheduling.

Awoman doesn’t need to be in precarious employment to have her rights violated. Women on irregular or precarious employment contracts have been found to be more at risk of sexual harassment (perhaps because they are less likely to take action against a colleague or employer who is harassing them) but as the #MeToo movement washes over social media, it is becoming increasingly hard to escape the reality that it is a rare industry in which sexual harassment isn’t a problem.

Awoman doesn’t need to be in precarious employment to have her rights violated. Women on irregular or precarious employment contracts have been found to be more at risk of sexual harassment (perhaps because they are less likely to take action against a colleague or employer who is harassing them) but as the #MeToo movement washes over social media, it is becoming increasingly hard to escape the reality that it is a rare industry in which sexual harassment isn’t a problem.

As ever, there is a data gap, with official statistics extremely hard to come by. The UN estimates (estimates are all we have) that up to 50% of women in EU countries have been sexually harassed at work. The figure in China is thought to be as high as 80%. In Australia a study found that 60% of female nurses had been sexually harassed.

The extent of the problem varies from industry to industry. Workplaces that are either male-dominated or have a male-dominated leadership are often the worst for sexual harassment. A 2016 study by the TUC found that 69% of women in manufacturing and 67% of women in hospitality and leisure “reported experiencing some form of sexual harassment” compared to an average of 52%. A 2011 U.S. study similarly found that the construction industry had the highest rates of sexual harassment, followed by transportation and utilities. One survey of senior level women working in Silicon Valley found that 90% of women had witnessed sexist behavior; 87% had been on the receiving end of demeaning comments by male colleagues; and 60% had received unwanted sexual advances. Of that 60%, more than half had been propositioned more than once, and 65% had been propositioned by a superior. One in three women surveyed had felt afraid for her personal safety.

Women have worked unpaid, underpaid, underappreciated, and invisibly, but they have always worked. But the modern workplace does not work for women.

Some of the worst experiences of harassment come from women whose work brings them into close contact with the general public. In these instances, harassment all too often seems to spill over into violence.

If incidents of physical violence aren’t a regular concern at your place of work, be grateful that you’re not a health worker. Research has found that nurses are subjected to “more acts of violence than police officers or prison guards.” A recent U.S. study similarly found that “health care workers required time off work due to violence four times more often than other types of injury.”

Following the research he conducted with fellow occupational health researcher Margaret Brophy, Jim Brophy concluded that the Canadian health sector was “one of the most toxic work environments that we had ever seen.” One worker recalled the time a patient “got a chair above his head,” noting that “the nursing station has been smashed two or three times.” Other patients used bed pans, dishes, even loose building materials as weapons against nurses.

But despite its prevalence, workplace violence in health care is “an underreported, ubiquitous, and persistent problem that has been tolerated and largely ignored.” This is partly because the studies simply haven’t been done. According to the Brophys’ research, prior to 2000, violence against health care workers was barely on the agenda: when in February 2017 they searched Medline for “workplace violence against nurses” they found “155 international articles, 149 of which were published from 2000 to the time of the search.”

But the global data gap when it comes to the sexual harassment and violence women face in the workplace is not just down to a failure to research the issue. It’s also down to the vast majority of women not reporting. And this in turn is partly down to organizations not putting in place adequate procedures for dealing with the issue. Women don’t report because they fear reprisals and because they fear nothing will be done — both of which are reasonable expectations in many industries. “We scream,” one nurse told the Brophys. “The best we can do is scream.”

The inadequacy of procedures to deal with the kind of harassment that female workers face is itself likely also a result of a data gap. Leadership in all sectors is male-dominated and the reality is that men do not face this kind of aggression in the way women do. And so, many organizations don’t think to put in procedures to deal adequately with sexual harassment and violence. It’s another example of how much a diversity of experience at the top matters for everyone — and how much it matters if we are serious about closing the data gap.

Women have always worked. They have worked unpaid, underpaid, underappreciated, and invisibly, but they have always worked. But the modern workplace does not work for women. From its location, to its hours, to its regulatory standards, it has been designed around the lives of men and it is no longer fit for purpose. The world of work needs a wholesale redesign — of its regulations, of its equipment, of its culture — and this redesign must be led by data on female bodies and female lives. We have to start recognizing that the work women do is not an added extra, a bonus that we could do without: women’s work, paid and unpaid, is the backbone of our society and our economy. As we enter a new decade, it’s about time we started valuing it.

Text adapted from Caroline Criado Perez’s Invisible Women, published by Abrams Press.

Text adapted from Caroline Criado Perez’s Invisible Women, published by Abrams Press.

Marker

Making you smarter about business. A new publication from Medium.

Follow

560

WRITTEN BY

Caroline Criado Perez

Follow

Writer, broadcaster, feminist activist, and author of Invisible Women: Data Bias in a World Designed for Men.

Invisible Women by Caroline Criado Perez (Abrams Press) was the winner of the 2019 Financial Times and McKinsey Business Book of the Year Award. In this excerpt from the book, the author describes some of the many ways in which women are harmed by workplaces designed without their needs in mind.

Itwas in 2008 that the big bisphenol A (BPA) scare got serious. Since the 1950s, this synthetic chemical had been used in the production of clear, durable plastics, and it was to be found in millions of consumer items from baby bottles to food cans to main water pipes. By 2008, 2.7 million tons of BPA was being produced globally every year, and it was so ubiquitous that it had been detected in the urine of 93% of Americans over the age of six. And then a U.S. federal health agency came out and said that this compound that we were all interacting with on a daily basis may cause cancer, chromosomal abnormalities, brain and behavioral abnormalities, and metabolic disorders. Crucially, it could cause all these medical problems at levels below the regulatory standard for exposure. Naturally, all hell broke loose.

Itwas in 2008 that the big bisphenol A (BPA) scare got serious. Since the 1950s, this synthetic chemical had been used in the production of clear, durable plastics, and it was to be found in millions of consumer items from baby bottles to food cans to main water pipes. By 2008, 2.7 million tons of BPA was being produced globally every year, and it was so ubiquitous that it had been detected in the urine of 93% of Americans over the age of six. And then a U.S. federal health agency came out and said that this compound that we were all interacting with on a daily basis may cause cancer, chromosomal abnormalities, brain and behavioral abnormalities, and metabolic disorders. Crucially, it could cause all these medical problems at levels below the regulatory standard for exposure. Naturally, all hell broke loose.Fearing a major consumer boycott, most baby-bottle manufacturers voluntarily removed BPA from their products, and while the official U.S. line on BPA is that it is not toxic, the EU and Canada are on their way to banning its use altogether. But the legislation that we have exclusively concerns consumers: no regulatory standard has ever been set for workplace exposure.

The story of BPA is about gender and class, and a cautionary tale about what happens when we ignore female medical health data. We have known that BPA can mimic the female hormone estrogen since the mid-1930s. And since at least the 1970s we have known that synthetic estrogen can be carcinogenic in women. But BPA carried on being used in hundreds of thousands of tons of consumer plastics, in CDs, DVDs, water and baby bottles, and laboratory and hospital equipment.

“It was ironic to me,” says occupational health researcher Jim Brophy, “that all this talk about the danger for pregnant women and women who had just given birth never extended to the women who were producing these bottles. Those women whose exposures far exceeded anything that you would have in the general environment. There was no talk about the pregnant worker who is on the machine that’s producing this thing.”

This is a mistake, says Brophy. Worker health should be a public health priority if only because “workers are acting as a canary for society as a whole. If we cared enough to look at what’s going on in the health of workers that use these substances every day,” it would have a “tremendous effect on these substances being allowed to enter into the mainstream commerce.”

But we don’t care enough. In Canada, where women’s health researcher Anne Rochon Ford is based, five women’s health research centers that had been operating since the 1990s, including Ford’s own, had their funding cut in 2013. It’s a similar story in the U.K., where “public research budgets have been decimated,” says Rory O’Neill. And so the “far better resourced” chemicals industry and its offshoots have successfully resisted regulation for years, dismissing studies and other evidence of the negative health impacts of their products.

The result is that workplaces remain unsafe. Brophy tells me that the ventilation he found in most auto-plastics factories was limited to “fans in the ceiling. So the fumes literally pass the breathing zone and head to the roof and in the summertime when it’s really hot in there and the fumes become visible, they will open the doors.” It’s the same story in Canadian nail salons, says Rochon Ford. There are no ventilation requirements, there are no training requirements. There is no legislation around wearing gloves and masks. And there is nobody following up on the requirements that do exist — unless someone makes a complaint.

The introduction of Big Data into a world full of gender data gaps can magnify and accelerate already-existing discriminations.

But who will make a complaint? Certainly not the women themselves. Women working in nail salons, in auto-plastics factories, in a vast range of hazardous workplaces, are poor, working class, often immigrants who can’t afford to put their immigration status at risk. And this makes them ripe for exploitation.

Auto-plastics factories tend not to be part of the big car companies like Ford. They are usually arms-length suppliers, “who tend to be nonunionized and tend to be able to get away with more employment-standard violations,” Rochon Ford tells me. Workers know that if they demand better protections the response will be “Fine, you’re out of here. There’s 10 women outside the door who want your job.” “We’ve heard factory workers tell us this in the exact same words,” says Rochon Ford.

If this sounds illegal, well, it may be. Employee rights vary from country to country, but they tend to include a right to paid sick and maternity leave, a right to a set number of hours, and protection from unfair and/or sudden dismissal. But these rights only apply if you are an employee. And, increasingly, many workers are not.

In many nail salons, technicians are technically independent contractors. This makes life much easier for the employers: the inherent risk of running a company based on consumer demand is passed on to workers, who have no guaranteed hours and no job security. Not enough customers today? Don’t come in and don’t get paid. Minor accident? You’re out of here, and forget about redundancy pay.

Nail salons are the tip of an extremely poorly regulated iceberg when it comes to employers exploiting loopholes in employment law. Zero-hour contracts, short-term contracts, employment through an agency, are all part of the Silicon Valley-built “gig economy.” But the gig economy is in fact often no more than a way for employers to get around basic employee rights. Casual contracts create a vicious cycle: the rights are weaker to begin with, which makes workers reticent to fight for the ones they do still have. And so those get bent too.

Naturally, the impact of what the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) has termed the “startling growth” of precarious work has barely been gender-analyzed. The ITUC reports that its feminized impact is “poorly reflected in official statistic and government policies,” because the “standard indicators and data used to measure developments on labor markets” are not gender-sensitive, and, as ever, data is often not sex-disaggregated, “making it sometimes difficult to measure the overall numbers of women.” There are, as a result, “no global figures related to the number of women in precarious work.”

But the regional and sector-specific studies that do exist suggest “an overrepresentation of women” in precarious jobs. A Harvard study on the rise of “alternative work” in America between 2005 and 2015 found that the percentage of women in such work “more than doubled,” meaning that “women are now more likely than men to be employed in an alternative work arrangement.”

This is a problem because while precarious work isn’t ideal for any worker, it can have a particularly severe impact on women. For a start, it is possible that it is exacerbating the gender pay gap: in the U.K. there is a 34% hourly pay penalty for workers on zero-hours contracts, a 39% hourly pay penalty for workers on casual contracts, and a 20% pay penalty for agency workers — which are on the increase as public services continue to be outsourced. But no one seems interested in finding out how this might be affecting women.

There is, to begin with, “limited scope for collective bargaining” in agency jobs. This is a problem for all workers, but can be especially problematic for women because evidence suggests that collective bargaining (as opposed to individual salary negotiation) could be particularly important for women. As a result, an increase in jobs like agency work that don’t allow for collective bargaining might be detrimental to attempts to close the gender pay gap.

But the negative impact of precarious work on women isn’t just about unintended side effects. It’s also about the weaker rights that are intrinsic to the gig economy. In the U.K., a female employee is only entitled to maternity leave if she is actually an employee. If she’s a “worker,” that is, someone on a short-term or zero-hours contract, she isn’t entitled to any leave at all, meaning she would have to quit her job and reapply after she’s given birth.

Another major problem with precarious work that disproportionately impacts female workers is unpredictable, last-minute scheduling. Women still do the vast majority of the world’s unpaid care work and, particularly when it comes to childcare, this makes irregular hours extremely difficult. The scheduling issue is being made worse by gender-insensitive algorithms. A growing number of companies use “just-in-time” scheduling software, which use sales patterns and other data to predict how many workers will be needed at any one time. They also respond to real-time sales analyses, telling managers to send workers home when consumer demand is slow.

It’s a system that works great for the companies that use the software to boost profits by shifting the risks of doing business onto their workers, and the increasing number of managers who are compensated on the efficiency of their staffing. It feels less great, however, for the workers themselves, particularly those with caring responsibilities. The introduction of Big Data into a world full of gender data gaps can magnify and accelerate already-existing discriminations: whether its designers didn’t know or didn’t care about the data on women’s unpaid caring responsibilities, the software has clearly been designed without reference to them.

The work that (mainly) women do (mainly) unpaid, alongside their paid employment is not an optional extra. This is work that society needs to get done. And getting it done is entirely incompatible with just-in-time scheduling designed entirely without reference to it. Which leaves us with two options: either states provide free, publicly funded alternatives to women’s unpaid work, or they put an end to just-in-time scheduling.

Awoman doesn’t need to be in precarious employment to have her rights violated. Women on irregular or precarious employment contracts have been found to be more at risk of sexual harassment (perhaps because they are less likely to take action against a colleague or employer who is harassing them) but as the #MeToo movement washes over social media, it is becoming increasingly hard to escape the reality that it is a rare industry in which sexual harassment isn’t a problem.

Awoman doesn’t need to be in precarious employment to have her rights violated. Women on irregular or precarious employment contracts have been found to be more at risk of sexual harassment (perhaps because they are less likely to take action against a colleague or employer who is harassing them) but as the #MeToo movement washes over social media, it is becoming increasingly hard to escape the reality that it is a rare industry in which sexual harassment isn’t a problem.As ever, there is a data gap, with official statistics extremely hard to come by. The UN estimates (estimates are all we have) that up to 50% of women in EU countries have been sexually harassed at work. The figure in China is thought to be as high as 80%. In Australia a study found that 60% of female nurses had been sexually harassed.

The extent of the problem varies from industry to industry. Workplaces that are either male-dominated or have a male-dominated leadership are often the worst for sexual harassment. A 2016 study by the TUC found that 69% of women in manufacturing and 67% of women in hospitality and leisure “reported experiencing some form of sexual harassment” compared to an average of 52%. A 2011 U.S. study similarly found that the construction industry had the highest rates of sexual harassment, followed by transportation and utilities. One survey of senior level women working in Silicon Valley found that 90% of women had witnessed sexist behavior; 87% had been on the receiving end of demeaning comments by male colleagues; and 60% had received unwanted sexual advances. Of that 60%, more than half had been propositioned more than once, and 65% had been propositioned by a superior. One in three women surveyed had felt afraid for her personal safety.

Women have worked unpaid, underpaid, underappreciated, and invisibly, but they have always worked. But the modern workplace does not work for women.

Some of the worst experiences of harassment come from women whose work brings them into close contact with the general public. In these instances, harassment all too often seems to spill over into violence.

If incidents of physical violence aren’t a regular concern at your place of work, be grateful that you’re not a health worker. Research has found that nurses are subjected to “more acts of violence than police officers or prison guards.” A recent U.S. study similarly found that “health care workers required time off work due to violence four times more often than other types of injury.”

Following the research he conducted with fellow occupational health researcher Margaret Brophy, Jim Brophy concluded that the Canadian health sector was “one of the most toxic work environments that we had ever seen.” One worker recalled the time a patient “got a chair above his head,” noting that “the nursing station has been smashed two or three times.” Other patients used bed pans, dishes, even loose building materials as weapons against nurses.

But despite its prevalence, workplace violence in health care is “an underreported, ubiquitous, and persistent problem that has been tolerated and largely ignored.” This is partly because the studies simply haven’t been done. According to the Brophys’ research, prior to 2000, violence against health care workers was barely on the agenda: when in February 2017 they searched Medline for “workplace violence against nurses” they found “155 international articles, 149 of which were published from 2000 to the time of the search.”

But the global data gap when it comes to the sexual harassment and violence women face in the workplace is not just down to a failure to research the issue. It’s also down to the vast majority of women not reporting. And this in turn is partly down to organizations not putting in place adequate procedures for dealing with the issue. Women don’t report because they fear reprisals and because they fear nothing will be done — both of which are reasonable expectations in many industries. “We scream,” one nurse told the Brophys. “The best we can do is scream.”

The inadequacy of procedures to deal with the kind of harassment that female workers face is itself likely also a result of a data gap. Leadership in all sectors is male-dominated and the reality is that men do not face this kind of aggression in the way women do. And so, many organizations don’t think to put in procedures to deal adequately with sexual harassment and violence. It’s another example of how much a diversity of experience at the top matters for everyone — and how much it matters if we are serious about closing the data gap.

Women have always worked. They have worked unpaid, underpaid, underappreciated, and invisibly, but they have always worked. But the modern workplace does not work for women. From its location, to its hours, to its regulatory standards, it has been designed around the lives of men and it is no longer fit for purpose. The world of work needs a wholesale redesign — of its regulations, of its equipment, of its culture — and this redesign must be led by data on female bodies and female lives. We have to start recognizing that the work women do is not an added extra, a bonus that we could do without: women’s work, paid and unpaid, is the backbone of our society and our economy. As we enter a new decade, it’s about time we started valuing it.

Text adapted from Caroline Criado Perez’s Invisible Women, published by Abrams Press.

Text adapted from Caroline Criado Perez’s Invisible Women, published by Abrams Press.Marker

Making you smarter about business. A new publication from Medium.

Follow

560

WRITTEN BY

Caroline Criado Perez

Follow

Writer, broadcaster, feminist activist, and author of Invisible Women: Data Bias in a World Designed for Men.

These days, finance is so fundamental to our everyday lives that it is difficult to imagine a world without it. But until the 1970s, the financial sector accounted for a mere 15 percent of all corporate profits in the US economy. Back then, most of what the financial sector did was simple credit intermediation and risk management: banks took deposits from households and corporations and loaned those funds to homebuyers and business. They issued and collected checks to facilitate payment. For important or paying customers, they provided space in their vaults to safeguard valuable items. Insurance companies received premiums from their customers and paid out when a costly incident occurred.

These days, finance is so fundamental to our everyday lives that it is difficult to imagine a world without it. But until the 1970s, the financial sector accounted for a mere 15 percent of all corporate profits in the US economy. Back then, most of what the financial sector did was simple credit intermediation and risk management: banks took deposits from households and corporations and loaned those funds to homebuyers and business. They issued and collected checks to facilitate payment. For important or paying customers, they provided space in their vaults to safeguard valuable items. Insurance companies received premiums from their customers and paid out when a costly incident occurred.

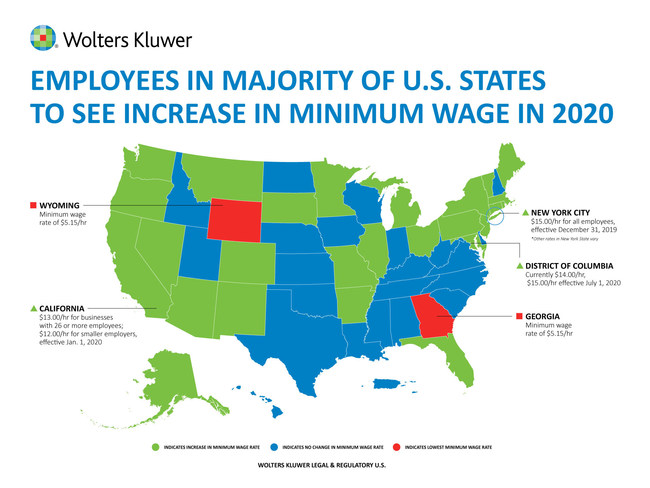

Employees in majority of U.S. states to see increase in minimum wage in 2020. (Credit: Wolters Kluwer Legal & Regulatory U.S.)

Employees in majority of U.S. states to see increase in minimum wage in 2020. (Credit: Wolters Kluwer Legal & Regulatory U.S.)