IN TIBET

First evidence of mysterious, ancient humans called Denisovans found outside of their cave

By Ashley Strickland, CNN

Wed May 1, 2019

CNN —

A 160,000-year-old Denisovan jawbone fossil has been found in a cave on the Tibetan plateau, according to a new study. This marks the first evidence of Denisovans found outside Denisova Cave in Siberia since the mysterious ancient human group was discovered in 2010.

Denisovans, who lived during a time that overlapped with Neanderthals, are known only from a few fossils discovered in a Siberian cave. But they also left a genetic legacy that lives on today in the DNA of some Asian, Australian and Melanesian humans. A Denisovan genome was sequenced in 2012 and compared with that of modern humans, revealing the trait.

Tibetans and Sherpas have a genetic variant that helps them live in low oxygen at high altitudes, which can be traced back to Denisovans.

But before the discovery of this jawbone, researchers wondered why this genetic variant existed. Tiny, fragmented remains of Denisovans had only ever been found in Denisova Cave, which sits at an altitude of 2,296 feet.

Baishiya Karst Cave on the Tibetan Plateau, where the jawbone was found, has an altitude of 10,761 feet.

No DNA was preserved in the fossil, but the researchers were able to extract ancient proteins and analyze them, as well as conduct radioisotopic dating of the fossil. The study on their findings was published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

A 160,000-year-old Denisovan jawbone fossil has been found in a cave on the Tibetan plateau, according to a new study. This marks the first evidence of Denisovans found outside Denisova Cave in Siberia since the mysterious ancient human group was discovered in 2010.

Denisovans, who lived during a time that overlapped with Neanderthals, are known only from a few fossils discovered in a Siberian cave. But they also left a genetic legacy that lives on today in the DNA of some Asian, Australian and Melanesian humans. A Denisovan genome was sequenced in 2012 and compared with that of modern humans, revealing the trait.

Tibetans and Sherpas have a genetic variant that helps them live in low oxygen at high altitudes, which can be traced back to Denisovans.

But before the discovery of this jawbone, researchers wondered why this genetic variant existed. Tiny, fragmented remains of Denisovans had only ever been found in Denisova Cave, which sits at an altitude of 2,296 feet.

Baishiya Karst Cave on the Tibetan Plateau, where the jawbone was found, has an altitude of 10,761 feet.

No DNA was preserved in the fossil, but the researchers were able to extract ancient proteins and analyze them, as well as conduct radioisotopic dating of the fossil. The study on their findings was published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

This cave sheltered some of the first known humans 300,000 years ago

The jawbone was well-preserved and featured a primitive shape, as well as a few large molars that were still attached.

At 160,000 years old, the fossil predates other evidence of ancient humans at such a high altitude in the area, which was previously set at between 30,000 and 40,000 years ago.

The age and features of the fossil are also similar to those of the oldest known Denisovan fossils from Denisova Cave, which suggests that the populations were closely related.

Dongju Zhang/Lanzhou University

The entrance to the Baishiya Karst Cave.

The jawbone was found by a monk in 1980 and eventually made its way to Lanzhou University, where researchers have been studying the cave site since 2010. They began analyzing the jawbone in 2016.

“Archaic hominins occupied the Tibetan Plateau in the Middle Pleistocene and successfully adapted to high-altitude low-oxygen environments long before the regional arrival of modern Homo sapiens,” said Dongju Zhang, study author and lecturer at Lanzhou University’s Research School of Arid Environment and Climate Change, in a statement.

Mysterious Denisovans interbred with modern humans more than once

The discovery shows that Denisovans lived in East Asia and adapted to the conditions there.

“Our analyses pave the way towards a better understanding of the evolutionary history of hominins in East Asia,” Jean-Jacques Hublin, study author and director of the Department of Human Evolution at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, said in a statement.

Evolutionary study suggests prehistoric human fossils ‘hiding in plain sight’ in Southeast Asia

A Homo erectus skull from Java, Indonesia. This pioneering species stands at the root of a fascinating evolutionary tree. Scimex

A Homo erectus skull from Java, Indonesia. This pioneering species stands at the root of a fascinating evolutionary tree. Scimex

March 23, 2021

Island Southeast Asia has one of the largest and most intriguing hominin fossil records in the world. But our new research suggests there is another prehistoric human species waiting to be discovered in this region: a group called Denisovans, which have so far only been found thousands of kilometres away in caves in Siberia and the Tibetan Plateau.

Our study, published in Nature Ecology and Evolution, reveals genetic evidence that modern humans (Homo sapiens) interbred with Denisovans in this region, despite the fact Denisovan fossils have never been found here.

Conversely, we found no evidence that the ancestors of present-day Island Southeast Asia populations interbred with either of the two hominin species for which we do have fossil evidence in this region: H. floresiensis from Flores, Indonesia, and H. luzonensis from Luzon in the Philippines.

Together, this paints an intriguing — and still far from clear — picture of human evolutionary ancestry in Island Southeast Asia. We still don’t know the precise relationship between H. floresiensis and H. luzonensis, both of which were distinctively small-statured, and the rest of the hominin family tree.

Get news that’s free, independent and based on evidence.Sign up for newsletter

And, perhaps more intriguingly still, our findings raise the possibility there are Denisovan fossils still waiting to be unearthed in Island Southeast Asia — or that we may already have found them but labelled them as something else.

An ancient hominin melting pot

Stone tool records suggest that both H. floresiensis and H. luzonensis are descended from Homo erectus populations that colonised their respective island homes about 700,000 years ago. H. erectus is the first ancient human known to have ventured out of Africa, and has first arrived in Island Southeast Asia at least 1.6 million years ago.

This means the ancestors of H. floresiensis and H. luzonensis diverged from the ancestors of modern humans in Africa around two million years ago, before H. erectus set off on its travels. Modern humans spread out from Africa much more recently, probably arriving in Island Southeast Asia 70,000-50,000 years ago.

We already know that on their journey out of Africa about 70,000 years ago, H. sapiens met and interbred with other related hominin groups that had already colonised Eurasia.

The first of these encounters was with Neanderthals, and resulted in about 2% Neanderthal genetic ancestry in today’s non-Africans.

The other encounters involved Denisovans, a species that has been described solely from DNA analysis of a finger bone found in Denisova Cave in Siberia.

Island Southeast Asia has one of the largest and most intriguing hominin fossil records in the world. But our new research suggests there is another prehistoric human species waiting to be discovered in this region: a group called Denisovans, which have so far only been found thousands of kilometres away in caves in Siberia and the Tibetan Plateau.

Our study, published in Nature Ecology and Evolution, reveals genetic evidence that modern humans (Homo sapiens) interbred with Denisovans in this region, despite the fact Denisovan fossils have never been found here.

Conversely, we found no evidence that the ancestors of present-day Island Southeast Asia populations interbred with either of the two hominin species for which we do have fossil evidence in this region: H. floresiensis from Flores, Indonesia, and H. luzonensis from Luzon in the Philippines.

Together, this paints an intriguing — and still far from clear — picture of human evolutionary ancestry in Island Southeast Asia. We still don’t know the precise relationship between H. floresiensis and H. luzonensis, both of which were distinctively small-statured, and the rest of the hominin family tree.

Get news that’s free, independent and based on evidence.Sign up for newsletter

And, perhaps more intriguingly still, our findings raise the possibility there are Denisovan fossils still waiting to be unearthed in Island Southeast Asia — or that we may already have found them but labelled them as something else.

An ancient hominin melting pot

Stone tool records suggest that both H. floresiensis and H. luzonensis are descended from Homo erectus populations that colonised their respective island homes about 700,000 years ago. H. erectus is the first ancient human known to have ventured out of Africa, and has first arrived in Island Southeast Asia at least 1.6 million years ago.

This means the ancestors of H. floresiensis and H. luzonensis diverged from the ancestors of modern humans in Africa around two million years ago, before H. erectus set off on its travels. Modern humans spread out from Africa much more recently, probably arriving in Island Southeast Asia 70,000-50,000 years ago.

We already know that on their journey out of Africa about 70,000 years ago, H. sapiens met and interbred with other related hominin groups that had already colonised Eurasia.

The first of these encounters was with Neanderthals, and resulted in about 2% Neanderthal genetic ancestry in today’s non-Africans.

The other encounters involved Denisovans, a species that has been described solely from DNA analysis of a finger bone found in Denisova Cave in Siberia.

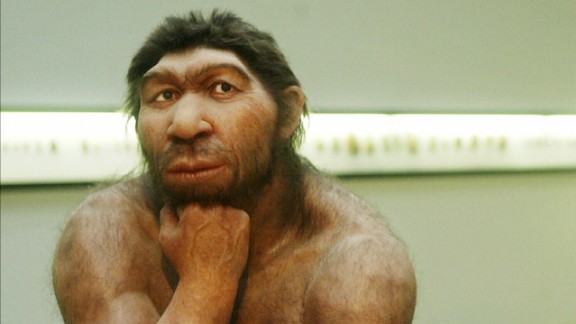

Only a handful of Denisovan fossils have been found, such as this jawbone unearthed in a Tibetan cave. Dongju Zhang/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Intriguingly, however, the largest amounts of Denisovan ancestry in today’s human populations are found in Island Southeast Asia and the former continent of Sahul (New Guinea and Australia). This is most likely the result of local interbreeding between Denisovans and modern humans — despite the lack of Denisovan fossils to back up this theory.

Read more: Southeast Asia was crowded with archaic human groups long before we turned up

To learn more, we searched the genome sequences of more than 400 people alive today, including more than 200 from Island Southeast Asia, looking for distinct DNA sequences characteristic of these earlier hominin species.

We found genetic evidence the ancestors of present-day people living in Island Southeast Asia have interbred with Denisovans — just as many groups outside Africa have similarly interbred with Neanderthals during their evolutionary history. But we found no evidence of interbreeding with the more evolutionarily distant species H. floresiensis and H. luzonensis (or even H. erectus).

This is a remarkable result, as Island Southeast Asia is thousands of kilometres from Siberia, and contains one of the richest and most diverse hominin fossil records in the world. It suggests there are more fossil riches to be uncovered.

So where are the region’s Denisovans?

There are two exciting possibilities that might reconcile our genetic results with with the fossil evidence. First, it’s possible Denisovans mixed with H. sapiens in areas of Island Southeast Asia where hominin fossils are yet to be found.

One possible location is Sulawesi, where stone tools have been found dating back at least 200,000 years. Another is Australia, where 65,000-year-old artefacts currently attributed to modern humans were recently found at Madjebebe.

Read more: Buried tools and pigments tell a new history of humans in Australia for 65,000 years

Alternatively, we may need to rethink our interpretation of the hominin fossils already discovered in Island Southeast Asia.

Confirmed Denisovan fossils are extremely rare and have so far only been found in central Asia. But perhaps Denisovans were much more diverse in size and shape than we realised, meaning we might conceivably have found them in Island Southeast Asia already but labelled them with a different name.

Given that the earliest evidence for hominin occupation of this region predates the divergence between modern humans and Denisovans, we can’t say for certain whether the region has been continuously occupied by hominins throughout this time.

It might therefore be possible that H. floresiensis and H. luzonensis (but also later forms of H. erectus) are much more closely related to modern humans than currently assumed, and might even be responsible for the Denisovan ancestry seen in today’s Island Southeast Asia human populations.

If that’s true, it would mean the mysterious Denisovans have been hiding in plain sight, disguised as H. floresiensis, H. luzonensis or H. erectus.

Solving these intriguing puzzles will mean waiting for future archaeological, DNA and proteomic (protein-related) studies to reveal more answers. But for now, the possibilities are fascinating.

Intriguingly, however, the largest amounts of Denisovan ancestry in today’s human populations are found in Island Southeast Asia and the former continent of Sahul (New Guinea and Australia). This is most likely the result of local interbreeding between Denisovans and modern humans — despite the lack of Denisovan fossils to back up this theory.

Read more: Southeast Asia was crowded with archaic human groups long before we turned up

To learn more, we searched the genome sequences of more than 400 people alive today, including more than 200 from Island Southeast Asia, looking for distinct DNA sequences characteristic of these earlier hominin species.

We found genetic evidence the ancestors of present-day people living in Island Southeast Asia have interbred with Denisovans — just as many groups outside Africa have similarly interbred with Neanderthals during their evolutionary history. But we found no evidence of interbreeding with the more evolutionarily distant species H. floresiensis and H. luzonensis (or even H. erectus).

This is a remarkable result, as Island Southeast Asia is thousands of kilometres from Siberia, and contains one of the richest and most diverse hominin fossil records in the world. It suggests there are more fossil riches to be uncovered.

So where are the region’s Denisovans?

There are two exciting possibilities that might reconcile our genetic results with with the fossil evidence. First, it’s possible Denisovans mixed with H. sapiens in areas of Island Southeast Asia where hominin fossils are yet to be found.

One possible location is Sulawesi, where stone tools have been found dating back at least 200,000 years. Another is Australia, where 65,000-year-old artefacts currently attributed to modern humans were recently found at Madjebebe.

Read more: Buried tools and pigments tell a new history of humans in Australia for 65,000 years

Alternatively, we may need to rethink our interpretation of the hominin fossils already discovered in Island Southeast Asia.

Confirmed Denisovan fossils are extremely rare and have so far only been found in central Asia. But perhaps Denisovans were much more diverse in size and shape than we realised, meaning we might conceivably have found them in Island Southeast Asia already but labelled them with a different name.

Given that the earliest evidence for hominin occupation of this region predates the divergence between modern humans and Denisovans, we can’t say for certain whether the region has been continuously occupied by hominins throughout this time.

It might therefore be possible that H. floresiensis and H. luzonensis (but also later forms of H. erectus) are much more closely related to modern humans than currently assumed, and might even be responsible for the Denisovan ancestry seen in today’s Island Southeast Asia human populations.

If that’s true, it would mean the mysterious Denisovans have been hiding in plain sight, disguised as H. floresiensis, H. luzonensis or H. erectus.

Solving these intriguing puzzles will mean waiting for future archaeological, DNA and proteomic (protein-related) studies to reveal more answers. But for now, the possibilities are fascinating.

João Teixeira

Research associate, University of Adelaide

Research associate, University of Adelaide

Kristofer M. Helgen

Chief Scientist and Director, Australian Museum Research Institute, Australian Museum

Disclosure statement

João Teixeira receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Kristofer M. Helgen received funding from the Australian Research Council’s Centre for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage (CABAH).

Chief Scientist and Director, Australian Museum Research Institute, Australian Museum

Disclosure statement

João Teixeira receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Kristofer M. Helgen received funding from the Australian Research Council’s Centre for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage (CABAH).

No comments:

Post a Comment