By Victoria Gill

Science correspondent, BBC News

Published8 hours ago

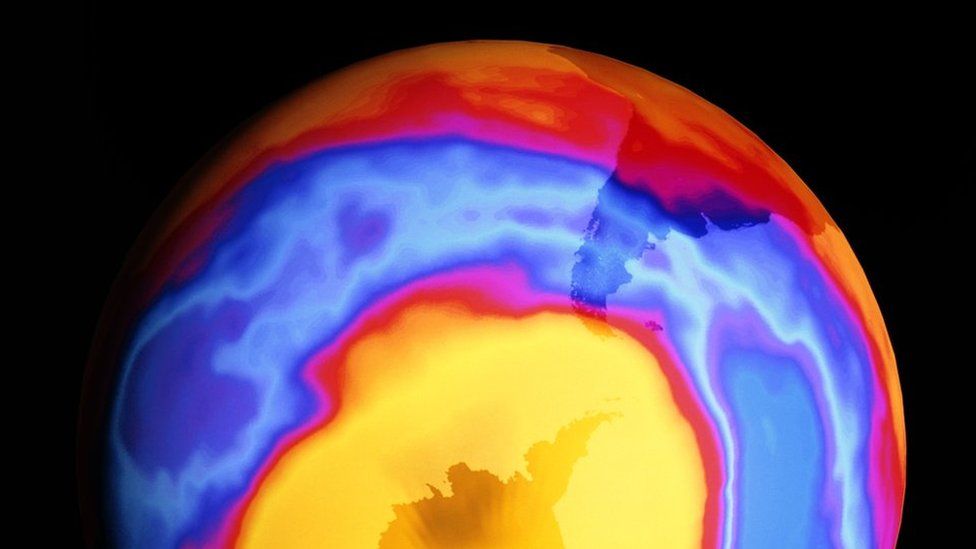

The ozone hole over Antarctica, in 2000

A worldwide ban on ozone-depleting chemicals in 1987 has averted a climate catastrophe today, scientists say.

The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, banning chemicals such as chlorofluorocarbons, has now simulated our "world avoided".

Without the treaty, Earth and its flora would have been exposed to far more of the Sun's ultraviolet (UV) radiation.

Former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan has called it "perhaps the single most successful international agreement".

Tortured plants

Continued and increased use of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) would have contributed to global air temperatures rising by an additional 2.5°C by the end of this century, the international team of scientists found.

Part of that would have been caused directly by CFCs, which are also potent greenhouse gases.

But the damage they cause the ozone layer would also have released additional planet-heating carbon dioxide - currently locked up in vegetation - into the atmosphere.

"In past experiments, people have exposed plants - basically tortured plants - with high levels of UV," lead researcher Dr Paul Young, of the Lancaster Environment Centre, said.

"They get very stunted - so they don't grow as much and can't absorb as much carbon."

A worldwide ban on ozone-depleting chemicals in 1987 has averted a climate catastrophe today, scientists say.

The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, banning chemicals such as chlorofluorocarbons, has now simulated our "world avoided".

Without the treaty, Earth and its flora would have been exposed to far more of the Sun's ultraviolet (UV) radiation.

Former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan has called it "perhaps the single most successful international agreement".

Tortured plants

Continued and increased use of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) would have contributed to global air temperatures rising by an additional 2.5°C by the end of this century, the international team of scientists found.

Part of that would have been caused directly by CFCs, which are also potent greenhouse gases.

But the damage they cause the ozone layer would also have released additional planet-heating carbon dioxide - currently locked up in vegetation - into the atmosphere.

"In past experiments, people have exposed plants - basically tortured plants - with high levels of UV," lead researcher Dr Paul Young, of the Lancaster Environment Centre, said.

"They get very stunted - so they don't grow as much and can't absorb as much carbon."

The world's vegetation would have been "stunted" by UV radiation damage

The scientists estimated there would be:

580 billion tonnes less carbon stored in forests, other vegetation and soils

an extra 165-215 parts per million (40-50%) of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere

"What we see in our 'world-avoided experiment' is an additional 2.5C warming above any warming that we would get from greenhouse-gas increases," Dr Young said.

But similar collective action to limit greenhouse-gas emissions was likely to be much more challenging.

"The science was listened to and acted upon - we have not seen that to the same degree with climate change," he told BBC Radio 4's Inside Science programme.

The experiment could appear to suggest hope for an "alternative future" that had avoided the worst consequences of climate change.

"But I would be cautious of using it as a positive example for the climate negotiations," Dr Young said.

"It's not [directly] comparable - but it's nice to have something positive to hold on to and to see that the world can come together."

No comments:

Post a Comment