FASTCOMPANY

12-06-21

Drivers for DoorDash, Instacart, and Gopuff have all staged work stoppages recently. But most workers won’t strike—and some actively love their gigs.

[Source Image: Boris Zhitkov/Getty]

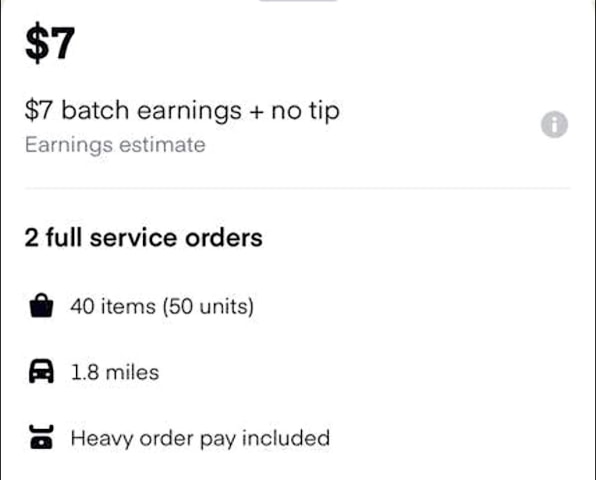

On October 16, an unknown number of drivers for grocery-delivery service Instacart went on strike. These shoppers, as Instacart calls its independent contractors, vowed to forgo logging on to the app that provides their dispatches. Other drivers who couldn’t afford to go without work still promised to reject the lowest-paying grocery orders, which pay $7 to the driver. The protestors demanded that Instacart meet a number of demands around higher fees, commissions, and tips, plus a reformed rating system.

You might have known about the strike if you read the technology business press or followed it on Twitter. But if you are an Instacart customer, you probably didn’t notice it. Organizers couldn’t provide a figure of how many people took part, but they concede it’s a small number compared to Instacart’s more than half a million shoppers.

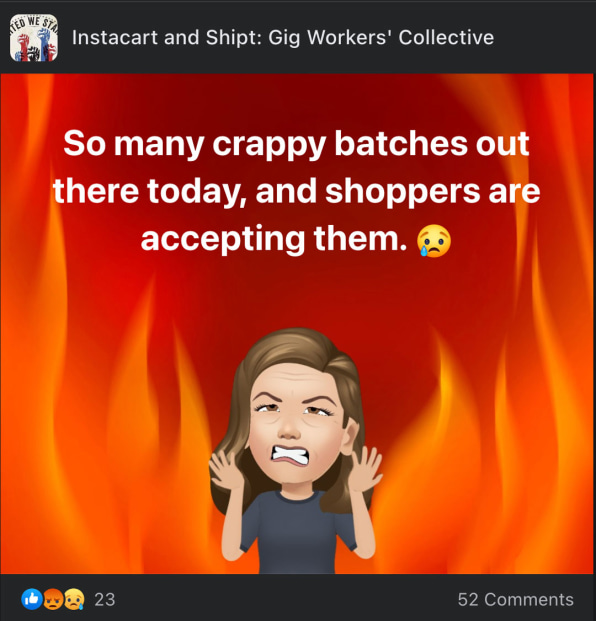

In a Facebook group, Instacart workers vent frustration at colleagues who settle

for low-paying assignments.

The striking Instacart drivers aren’t the only gig workers who have found it difficult to improve their working conditions by banding together. Many sectors of the service economy are facing dire labor shortages, as part of the “Great Resignation.” In theory, that should give the remaining workers plenty of leverage to demand better pay. But many gig-economy companies, especially delivery services, have an overabundance of workers with little or no power to negotiate.

“The operational level of Instacart is one that’s reached a level that’s beyond what we can reach as workers,” says Willy Solis, a lead organizer with the Gig Workers Collective (GWC), which coordinated the strike. In fact, Instacart workers have been organizing protests against the company for years, including in late September, with little to no effect.

Labor organizing has made inroads lately in traditional industries, as varied as food factories, hospitals, and newsrooms. But the diffuse nature of gig work, in which everyone is on their own, makes it hard for workers to join together. What’s more, labor organizing seems to go against the ethos of being an independent contractor for many workers.

Striking drivers for food-delivery service DoorDash ran into the same issues last summer. On July 31, some of them logged off the app to demand a higher base pay, which can be as little as $2 per order. They also sought clarity on how much tip to expect, which can make the difference between earning and losing money. They recommended that drivers instead log on to DoorDash’s rival Uber Eats, which has not faced such worker strikes in the United States (although it has abroad, including in South Africa and the U.K).

But like Instacart, DoorDash has no shortage of labor in the U.S., boasting more than 1 million active “dashers,” as its contractors are called. Even fellow dashers haven’t noticed the effects. “I’ve been doing this for five years now,” says Anna Witte, a dasher in Fremont, California. “And I have not seen anybody take any strike on DoorDash or anything else. So it hasn’t affected anybody getting orders.”

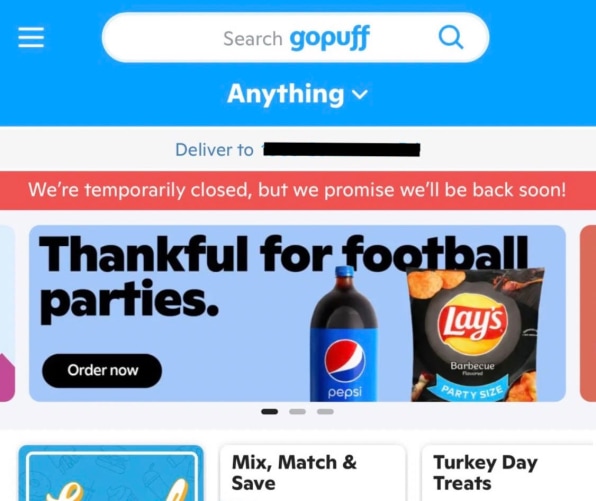

Drivers for rapid-delivery service Gopuff are the latest to go on strike, staging a one-day walkout on November 23 to demand better base pay and other changes. A far smaller company than Instacart or DoorDash, Gopuff has only about 10,000 contractors. And strike organizers estimate that about 200 to 300 people took part.

The striking Instacart drivers aren’t the only gig workers who have found it difficult to improve their working conditions by banding together. Many sectors of the service economy are facing dire labor shortages, as part of the “Great Resignation.” In theory, that should give the remaining workers plenty of leverage to demand better pay. But many gig-economy companies, especially delivery services, have an overabundance of workers with little or no power to negotiate.

“The operational level of Instacart is one that’s reached a level that’s beyond what we can reach as workers,” says Willy Solis, a lead organizer with the Gig Workers Collective (GWC), which coordinated the strike. In fact, Instacart workers have been organizing protests against the company for years, including in late September, with little to no effect.

Labor organizing has made inroads lately in traditional industries, as varied as food factories, hospitals, and newsrooms. But the diffuse nature of gig work, in which everyone is on their own, makes it hard for workers to join together. What’s more, labor organizing seems to go against the ethos of being an independent contractor for many workers.

Striking drivers for food-delivery service DoorDash ran into the same issues last summer. On July 31, some of them logged off the app to demand a higher base pay, which can be as little as $2 per order. They also sought clarity on how much tip to expect, which can make the difference between earning and losing money. They recommended that drivers instead log on to DoorDash’s rival Uber Eats, which has not faced such worker strikes in the United States (although it has abroad, including in South Africa and the U.K).

But like Instacart, DoorDash has no shortage of labor in the U.S., boasting more than 1 million active “dashers,” as its contractors are called. Even fellow dashers haven’t noticed the effects. “I’ve been doing this for five years now,” says Anna Witte, a dasher in Fremont, California. “And I have not seen anybody take any strike on DoorDash or anything else. So it hasn’t affected anybody getting orders.”

Drivers for rapid-delivery service Gopuff are the latest to go on strike, staging a one-day walkout on November 23 to demand better base pay and other changes. A far smaller company than Instacart or DoorDash, Gopuff has only about 10,000 contractors. And strike organizers estimate that about 200 to 300 people took part.

A Gopuff warehouse in Athens, GA temporarily shut down, possibly due to the strike.

Gopuff strike organizers reported to Fast Company that drivers didn’t show up for, or left early from, scheduled shifts in at least five warehouse locations—including at least one that temporarily shut down. They noted pay boosts, meant to attract more workers, offered at six locations on strike day. For perspective, the company has more than 550 facilities across the U.S.

“Gopuff tells Fast Company that delivery times were normal across markets for a Tuesday. Further, Gopuff says that it often issues pay boosts when demand spikes. In a statement, the company said, “In the case that we are not able to respond quickly to uptick in orders in some of our smaller volume markets, we may choose to briefly pause customer orders until we are able to effectively address the current demand.”

Even if they’ve scored a few small victories, strikers’ actions have fallen well short of affecting any gig company’s business on a scale that causes real pain. For various reasons, very few workers feel motivated to skip work in protest, even for just a day.

Gopuff strike organizers reported to Fast Company that drivers didn’t show up for, or left early from, scheduled shifts in at least five warehouse locations—including at least one that temporarily shut down. They noted pay boosts, meant to attract more workers, offered at six locations on strike day. For perspective, the company has more than 550 facilities across the U.S.

“Gopuff tells Fast Company that delivery times were normal across markets for a Tuesday. Further, Gopuff says that it often issues pay boosts when demand spikes. In a statement, the company said, “In the case that we are not able to respond quickly to uptick in orders in some of our smaller volume markets, we may choose to briefly pause customer orders until we are able to effectively address the current demand.”

Even if they’ve scored a few small victories, strikers’ actions have fallen well short of affecting any gig company’s business on a scale that causes real pain. For various reasons, very few workers feel motivated to skip work in protest, even for just a day.

DISAGREEMENT OVER PAY

Pay is the main factor driving the workers who do strike. In September, for instance, Gopuff workers on scheduled shifts in the company’s hometown of Philadelphia saw their minimum guaranteed hourly pay cut from about $12 to about $7.75 (pay rates vary by location). Workers are now demanding $20 per hour, plus expenses. Once tips are factored in, Gopuff says that workers average $18 to $25 per hour; but Candace Hinson, a driver and strike organizer in Philadelphia, estimates that she’s now making as little as $10 per hour.

As shown in Instacart’s driver app, its lowest-paying assignments start at $7.

Instacart workers point to changes in the pay formula made in 2018. Once, workers were paid on a per-order, per-item basis. Now pay is determined by an algorithm that they believe ends up paying less. Shopper assignments, called batches, can contain up to three grocery orders and offer $7 to $10 minimum payments (before tips). Postings of $7 batches, some of which can take an hour to fulfill, are common in the Facebook group Instacart and Shipt: Gig Workers’ Collective.

Why don’t drivers simply pass over the low-paying offers? That’s what Anna Witte does. “I make really good money doing DoorDash,” says Witte, who says she averages about $40 per hour. “So I wouldn’t see a reason to do a strike.” Her earnings beat DoorDash’s estimated national average of $25 per hour, including tips. Witte attributes some of her good fortune to being in a busy, affluent market.

Perhaps the most successful gig worker organization is the group #DeclineNow, which encourages members to reject any DoorDash gig that advertises a fee under $7. Founded in late 2019, it’s based on gaming the algorithm. If no one takes a low-paying assignment, the system has to offer progressively higher fees until someone bites.

Boasting over 35,000 members, the #DeclineNow Facebook group is massive compared to its Instacart and Shipt counterpart (with 1,800) and Gopuff workers’ current organizing efforts. But only a tiny fraction of DoorDash’s million-plus dashers participate.

The founders claim that their movement is big enough to affect wages, and there’s some anecdotal evidence of that in the Seattle area, based on data from gig-pay tracking service Solo. Hourly earnings on DoorDash increased from about $24 per hour in March to about $30 per hour in May, as #DeclineNow started gaining traction. “You can’t prove causation, but we did see quite a dramatic increase in average hourly earnings during that time,” says Bryce Bennett, the CEO of Solo and a former regional manager for Uber. “And we also saw a slight uptick in tips from about $5 to $6 per order.”

If #DeclineNow is succeeding, it’s not through workers resorting to traditional strike tactics. Rather, the group is driving a hard bargain with its business partner, DoorDash. (We tried to learn more about #DeclineNow by interviewing its cofounders, but they declined to speak with us unless we paid a consultation fee.)

Instacart workers point to changes in the pay formula made in 2018. Once, workers were paid on a per-order, per-item basis. Now pay is determined by an algorithm that they believe ends up paying less. Shopper assignments, called batches, can contain up to three grocery orders and offer $7 to $10 minimum payments (before tips). Postings of $7 batches, some of which can take an hour to fulfill, are common in the Facebook group Instacart and Shipt: Gig Workers’ Collective.

Why don’t drivers simply pass over the low-paying offers? That’s what Anna Witte does. “I make really good money doing DoorDash,” says Witte, who says she averages about $40 per hour. “So I wouldn’t see a reason to do a strike.” Her earnings beat DoorDash’s estimated national average of $25 per hour, including tips. Witte attributes some of her good fortune to being in a busy, affluent market.

Perhaps the most successful gig worker organization is the group #DeclineNow, which encourages members to reject any DoorDash gig that advertises a fee under $7. Founded in late 2019, it’s based on gaming the algorithm. If no one takes a low-paying assignment, the system has to offer progressively higher fees until someone bites.

Boasting over 35,000 members, the #DeclineNow Facebook group is massive compared to its Instacart and Shipt counterpart (with 1,800) and Gopuff workers’ current organizing efforts. But only a tiny fraction of DoorDash’s million-plus dashers participate.

The founders claim that their movement is big enough to affect wages, and there’s some anecdotal evidence of that in the Seattle area, based on data from gig-pay tracking service Solo. Hourly earnings on DoorDash increased from about $24 per hour in March to about $30 per hour in May, as #DeclineNow started gaining traction. “You can’t prove causation, but we did see quite a dramatic increase in average hourly earnings during that time,” says Bryce Bennett, the CEO of Solo and a former regional manager for Uber. “And we also saw a slight uptick in tips from about $5 to $6 per order.”

If #DeclineNow is succeeding, it’s not through workers resorting to traditional strike tactics. Rather, the group is driving a hard bargain with its business partner, DoorDash. (We tried to learn more about #DeclineNow by interviewing its cofounders, but they declined to speak with us unless we paid a consultation fee.)

THE VALUE OF FREEDOM

Regardless of pay, some workers are attracted to gig work for the freedom and flexibility it provides. “The pandemic and everything that’s happened has made clear how difficult it is for low-wage workers to balance work and anything else in their lives,” says Shelly Steward, director of the Aspen Institute’s Future of Work Initiative. Most retail workers have no influence over—and little notice about—their schedules, she says.

But in the gig economy, workers make their own hours. “Lots of [shoppers] have kids,” says Steve Labinski, an Instacart shopper in Dallas and author of the book Shop Like a Pro. “So they’ll send the kids to school, and during the day, they can deliver groceries.” Anna Witte delivers for DoorDash after she drops her son at school.

FLEXIBILITY AND FAST CASH ARE BRINGING A LOT OF NEW RECRUITS INTO GIG WORK.

Part-time Gopuff driver and strike organizer Ronald Moody concedes that he doesn’t work the most lucrative times. During early morning shifts, he can sit idle for hours. “I have no problem getting up that early,” he says. “And it gives me the flexibility to do other stuff the rest of my day.” For Moody, that other stuff includes his main work as a financial services compliance consultant.

He’s far from the only person doing gig work as a side hustle.

“Maybe they’re in between jobs, or they’re truly just doing it as supplemental income,” says Lindsey Cameron, an assistant professor of management at the Wharton School of Business. “[Those] people are going to be less vested into the platform and less vested into getting rights for workers.” DoorDash estimates that 90% of dashers spend less than 10 hours per week delivering. Gopuff says that 70% of drivers work less than 20 hours.

Flexibility and fast cash are bringing a lot of new recruits into gig work, especially delivery services such as Cornershop and Postmates (both of which are owned by Uber), DoorDash, Gopuff, Grubhub, Instacart, Shipt, and Uber Eats. In the spring of 2020, as the pandemic prompted more people to order delivery, Instacart expanded its pool of shoppers from about 200,000 to about 500,000 in a matter of weeks. As the economy opened up in 2021, demand for grocery delivery tapered off, but the pool of drivers remains the same.

Workers aren’t just coming in from traditional job sectors but also from ride-hailing services such as Lyft and Uber, says Harry Campbell, who covers the gig economy through his media company the Rideshare Guy. (Uber won’t say how many drivers work for it in rideshare or food delivery, but reports that it’s taken on 640,000 new drivers since January.)

DIVIDED POLITICS

Views on economics—and associated politics—divide gig workers. While pro-strike activists demand reforms, other workers have a free-market philosophy, rooted in the nature of freelance work.

“You strike when you want to protest your boss,” says Labinski. “When you’re a self-employed gig worker, you are your own boss. So you’re only punishing yourself.”

Striking gig workers “want to have their cake and eat it too,” says Chad Polenz, a Florida-based delivery driver who covers the industry on his YouTube channel GigTube. “They want all the benefits and protections of being a W-2 [on-staff] employee, but they want all the freedom of being a 1099 independent contractor. And you can’t have it both ways.”

Working mainly DoorDash and Instacart, Polenz reckons that he makes from about $20 to over $30 per hour, depending on the day. And he agrees with gig-worker activists that Instacart pay has declined over the years. (An Instacart representative told Fast Company that the earnings formula has stayed the same since February 2019.) Yet Polenz is not joining the strikes and protests.

For Polenz, it’s partly about politics. “The spokespeople for the Gig Workers Collective, they’re all like Bernie Sanders-type people, antifa-type people, BLM-type people,” he says. Gig Workers Collective founder Vanessa Bain has the terms “BLM,” “Antifa,” and “Capitalism Ruins Everything Around Me,” in her Twitter bio. Willy Solis’s Twitter page features a photo of Bernie Sanders. As a libertarian, Polenz doesn’t feel welcome. He doesn’t agree with the typical slant of press coverage either.

“The media have a more critical perspective on gig work,” says Wharton professor Cameron. “And when I started actually interviewing drivers, a lot of them have very different experiences,” she says, describing the research for her 2021 study “‘Making Out’ While Driving.”

For some, gig work has been a step up from low-skilled and dangerous jobs that often paid less. One immigrant Cameron spoke to described himself as “living the American dream,” as a gig worker. Far from anti-capitalist, some workers see themselves in partnership with the gig companies. Cameron spoke to a rideshare driver who told her, “It’s a pleasure to work with them. To work with them, because we’re partners, so I don’t say work for them.”

THE PR BENEFITS OF STRIKING

While strikes and protests may not substantially slow the gig companies’ business, they do generate publicity that affects politicians. “Some of the strikes have really functioned to bring attention to the issues facing gig workers,” says Ken Jacobs, chair of the UC Berkeley Center for Labor Research and Education. “And the work and organization of gig workers had an effect on California passing AB5.”

He’s referring to a 2019 California law that classified gig workers as employees. It entitled them to protections and benefits, such as workers comp, unemployment insurance, paid sick and family leave, and health insurance. The law was spearheaded by Lorena Gonzalez, the former head of the San Diego-Imperial Counties Labor Council, who was elected to the California State Assembly in 2013.

Jacobs also cites the influence of strikes in Seattle and New York City. In 2020, Seattle passed ordinances that guaranteed premium pay for food-delivery workers and paid sick leave for all gig workers. In September, New York City passed six laws to protect food-delivery workers, including providing better information about assignments and tips. It also launched a study to determine the minimum pay for couriers.

But politics and public opinion are fickle. In 2020, voters in famously progressive California overwhelmingly approved Proposition 22, which undid the AB5 protections. (They may have been swayed by a $206 million campaign funded by Uber, DoorDash, Lyft, Instacart, and Postmates.) A recent court ruling held that Prop 22 is unconstitutional, but nonemployee status of gig workers persists.

[Photo: courtesy of Working Washington]

A strike is “definitely bad publicity for Instacart or whatever company,” says Polenz. “But the public has a very short memory. So after like a week or two, people just forget about it.”

The tech industry is full of companies that can weather negative publicity. (Think Amazon, Facebook, Google, Uber, and so many more.) Consumers may sympathize with downtrodden workers. But the utility and convenience of these services make it hard for them to break up with the companies, and hard for governments to exert much control.

Organized labor has been the most effective means to truly turn the direction of a company. But it requires overwhelming numbers. With a huge surplus of labor and scant appetite for activism among their ranks, gig workers are mightily challenged to change their predicament.

This article has been updated to reflect additional input from Gopuff.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Sean Captain is a business, technology, and science journalist based in North Carolina. Follow him on Twitter @seancaptain.

No comments:

Post a Comment