Fusion Experiment Reaches Vital Power Generation Milestone

The world struggles to produce enough power as it is, but there’s a real possibility we will have to phase out fossil fuels in the coming decades. And what’s left then? Wind? Solar? We might be able to skip the middleman and make our own solar energy via fusion, but the technology to make that a reality is still evolving. However, researchers from the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) say they’ve reached an important milestone in fusion power generation. For the first time, a fusion reaction has generated more power than the fuel absorbed. This puts humanity on the verge of creating usable energy by harnessing the power of the sun.

The team conducted this experiment at the National Ignition Facility (NIF) back in August, and the results have not yet been peer reviewed. LLNL will submit a paper soon. The news initially broke in August, but interest has been trending upward as the team gets ready to try again. LLNL has also been talking more about how it improved fusion efficiency in the NIF, which it has by a huge margin. For example, the fuel in the experiment was contained inside a new high-density carbon (i.e. diamond) target capsule.

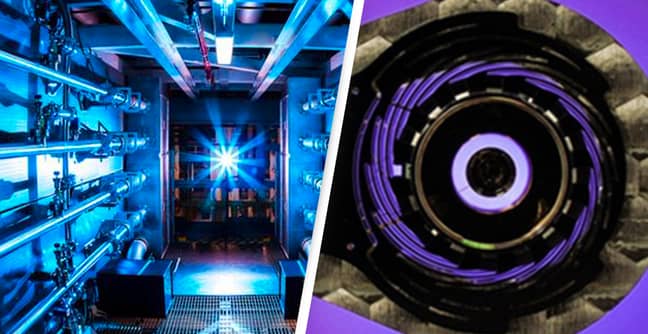

The NIF is the size of three football fields, and it’s equipped with 192 high-powered lasers. The lasers focus on a small capsule of deuterium and tritium (hydrogen isotopes). The lasers hit an object called a hohlraum, which converts the laser into X-rays that bombard the fuel and approximate the heat and pressure of a star, but only for a moment. Initial analysis of the August experiment shows that the reaction generated more than 10 quadrillion watts of fusion power for 100 trillionths of a second. That’s a big achievement, but some of the initial reports of success conflated fuel absorption with ignition, and that’s not where we are.

While this is an important step forward, it’s still short of ignition — the point at which a sustained fusion reaction can generate net energy. This experiment achieved a record 1.3-megajoule energy output, the NIF used a total of 1.9 megajoules. That’s not to take away from the importance of this achievement. “Gaining experimental access to thermonuclear burn in the laboratory is the culmination of decades of scientific and technological work stretching across nearly 50 years,” said Los Alamos National Laboratory Director Thomas Mason. Even though we can’t yet generate energy from fusion, the efficiency of these techniques is improving rapidly. In 2013, the NIF was managing a mere 14 kilojoules, and now it’s two orders of magnitude higher.

It will take time for the scientific community to dissect this latest work, but the LLNL team reports improvements in laser focusing, hohlraum efficiency, and target fabrication boosted energy production by more than eight times compared to experiments just a few months earlier, and 25 times higher than NIF’s 2018 record. LLNL also plans to repeat the experiment to confirm its results. It began setting up the experiment after the initial success, so it shouldn’t be much longer before the team is ready to fire up the NIF again.

Now read:

- China’s Fusion Reactor Sets World Record by Running for 101 Seconds

- MIT Plans New Fusion Reactor That Could Actually Generate Power

- The Navy Just Patented a Compact Fusion Reactor, but Will It Work?

Fusion Reaction Creates More Energy

Than Absorbed By Fuel For First Time

Physicists have made history with an experiment that saw a fusion reaction create more energy than the amount absorbed by the fuel used to trigger it.

Described by scientists at the National Ignition Facility at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory as a ‘historic step forward for inertial confinement fusion research’, the fusion reaction achieved a record energy output of 1.3 megajoules.

The output, achieved in August, proved to be eight times greater than experiments conducted just a few months prior, and 25 times greater than experiments performed in 2018.

The ultimate goal of the inertial confinement fusion experiment was to achieve ignition; a point at which the energy created by the fusion process proves greater than the total energy input.

Though the experiment did not quite succeed in achieving ignition, its results proved noteworthy as the fuel capsule used generated more than five times as much energy as it absorbed in the fusion process, Science Alert reports.

Kim Budil, director of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, said in a press release the experiment opened ‘a fundamentally new regime for exploration and the advancement of our critical national security missions’.

Budil continued:

It is also a testament to the innovation, ingenuity, commitment and grit of this team and the many researchers in this field over the decades who have steadfastly pursued this goal.

For me, it demonstrates one of the most important roles of the national labs – our relentless commitment to tackling the biggest and most important scientific grand challenges and finding solutions where others might be dissuaded by the obstacles.

Following the experiment earlier this year, the team planned to perform more studies to see if they could replicate their results and study the process in greater detail, as well as to work out how to further increase energy efficiency.

The physicists will be submitting a paper on their results for peer review.

No comments:

Post a Comment