Henry George has much to teach us about power and privilege today.

Joseph Addington

Writes Progress and Poverty ·

Jul 25,2022

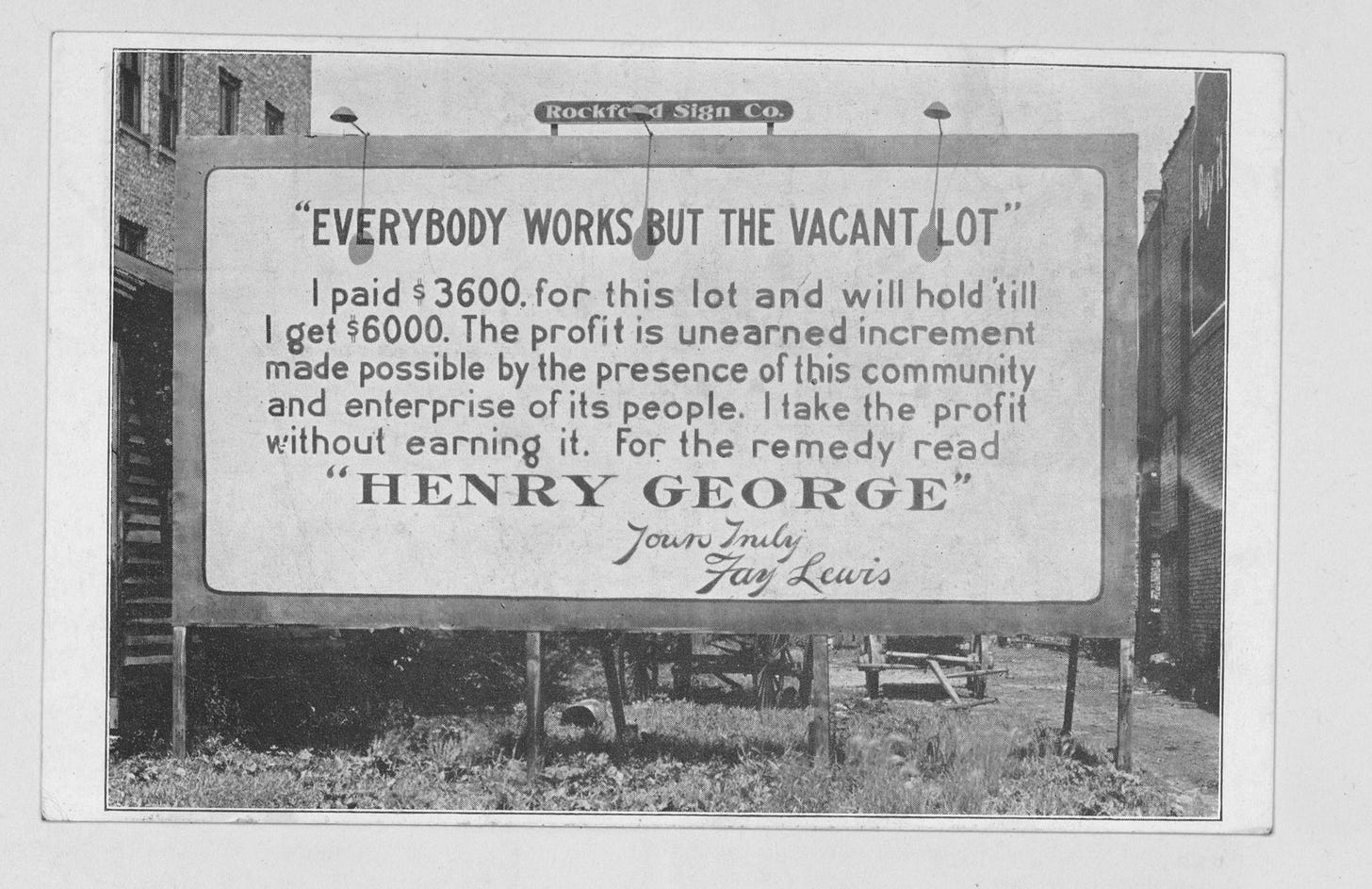

Postcard featuring a quote from Henry George, 1900. From the New York Public Library. (Photo by Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images).

We live in tumultuous times. Rampant social unrest, political instability, and rising populist anger have combined to create a particularly difficult cultural moment. Much of this is motivated by an increase in economic inequality, which in recent years has reached levels not seen since before the Great Depression. Social mobility has decreased. Housing—or, more specifically, land for housing—has become so expensive that many young people wonder if they will ever be able to afford a home at all. Many people have begun to feel that the American dream is dying, that the system is rigged, and that a better life is out of reach.

In many ways, our situation resembles the Gilded Age, a period during the late 19th century in the aftermath of the Industrial Revolution. One Gilded Age figure who has important lessons for today is Henry George. A journalist and political economist, George is now mostly forgotten, but during his own time he was a ubiquitous public figure. Through a careful examination of privilege, rights, and the sources of economic inequality, he has inspired millions worldwide to fight for a freer and more just society.

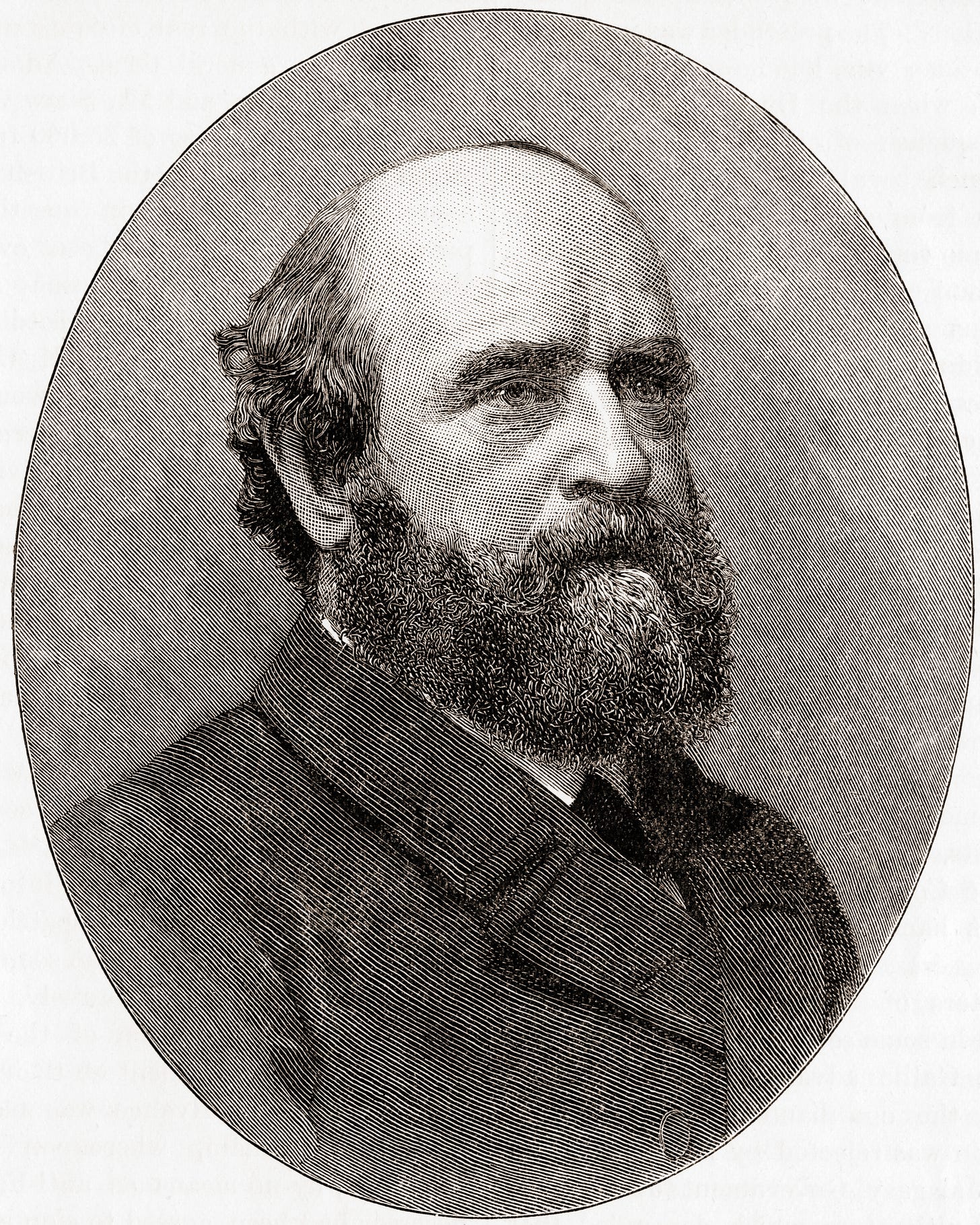

Henry George. (Photo by: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

By the time of his death in 1897, Henry George was one of the most influential men in the Western world. He was the best selling American economist ever published, and an estimated 200,000 people attended his funeral. Yet despite his immense popularity, he had humble beginnings. Growing up the son of working-class parents, he settled in San Francisco and began working in the newspaper business, although financial hardship left his family near starvation. Eventually he worked his way up through the printing industry and became a well-regarded editor and journalist.

His time in poverty left George contemplating the great questions that bedeviled the Gilded Age. If technology was improving and productivity increasing—if more wealth was being generated faster than ever before—why was there so much abject poverty? Why were the cities, where new manufacturing technology and economies of scale were concentrated, deep in the refuse of tenements?

George realized that the problem lay in the monopolization of the Earth. The value of urbanization and technological progress was being captured by private land ownership. As technology improved and urbanization increased, the value of the land also increased. The result was soaring land rents, which soaked up the gains in productivity, leaving workers impoverished. (“Rent” here refers to the wealth and advantages derived from control over a scarce resource, as opposed to the colloquial use of “rent” meaning money paid to lease housing.) The primary beneficiaries of this process were landowners, who could extract more value from both workers and businesses who needed access to the land to live or set up shop, without the landowners providing any positive contribution to the economy themselves.

In 1879, George published a book titled Progress and Poverty, in which he built on the work of earlier liberals to argue that the Earth and its natural resources belong to mankind in common. Simply put, George believed that people own what they create with their labor. Because no-one created the land, the land belongs to everyone in common. But the absolute necessity of land for human life, both to live and to work, allows landowners to extract immense amounts of wealth from workers and business owners by charging for access. This activity incentivizes speculation, prices people out of their homes, makes it more difficult to operate a business, and creates decaying cities and urban sprawl. When land is monopolized in this way, the rents it produces enrich the landowners at the expense of society and cause seemingly intractable poverty.

The remedy George suggested was simple: replacing other taxes with a Land Value Tax (LVT). LTV is a tax on the unimproved value of land. It is premised on the idea that taxing the value of land prevents rent-seeking and speculation while unleashing the productive capacities of the economy. Unlike property taxes, which punish development, LVT incentivizes landowners to put land to productive use because the tax remains the same no matter how the land is used. Productive use can include using the land for commercial purposes, building housing on it, or selling it to others who will use it.

Furthermore, land value taxes fall solely on the owners of the land, who find it much harder to pass the burden of the tax onto their tenants. This is because landlords charge the highest price the rental market can bear, which is determined by supply and demand. Because an LVT doesn’t impact the supply of land, and doesn’t cause any rise in rental demand, the market for rents does not shift in response to the introduction of an LVT. Landlords who try to raise their rents will find that their tenants eventually move out and switch to landlords charging lower prices (the existence of low-value land that is taxed at small or zero rates guarantees cheaper options). Landlords cannot afford to lose tenants in this way, given the cost LVT imposes on people who hold land without using it.

Henry George and the “Single Taxers,” as his followers called themselves, were not advocating for anything novel. In fact, they drew on a rich tradition of American and English liberalism to make their case.

Liberalism was born in the shadows of feudalism, where the aristocracy was characterized by privilege and exclusive rights. The most fundamental of these was the right to land, from which aristocrats extracted rent that funded their lavish lifestyle and freed them from the necessity of labor. Accordingly, liberals and proto-liberals from Adam Smith to John Stuart Mill fought against concentrated land ownership. In the U.S., Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Paine advocated for a taxation of land values.

In fact, George wrote in Progress and Poverty that his ideas were “the carrying out in letter and spirit of the truth enunciated in the Declaration of Independence.” George argued that the rights promised by the Founders are “denied when the equal right to land—on which and by which men alone can live—is denied. Equality of political rights will not compensate for the denial of the equal right to the bounty of nature.”

His argument, then, was that classical liberalism was incomplete. It had managed to break the political power of the aristocracy by stripping them of their unique political privileges—but it had left intact the economic privileges of landlordism and monopolies which had allowed them to accumulate that power in the first place.

As a philosophy which provides a fresh perspective on building a free and fair society, Georgism provides solutions to the increasing economic unfairness that is beginning to chip away at the stability of Western liberal democracies. It can revitalize a liberalism that seems impotent to address the angry calumnies of populists and demagogues.

The most obvious area is taxation. Land remains one of the biggest sources of rent extraction in the modern economy. A modern LVT would replace inefficient sales, property, income, and capital gains taxes, eliminating the penalties that the state levies on people who create a successful business or build a home.

And Georgism does not stop at LVT. In order to guarantee equality of opportunity, all the various forms of monopolistic rent-seeking need to be addressed. America’s mineral and oil industries are worth hundreds of billions of dollars a year, much of which takes the form of revenue made by companies who have the right to access natural energy resources. 21st century Georgism would mean moving to a model more like Norway’s, which heavily taxes profits from the extraction of oil, while offering deductions when companies engage in technological improvements and exploration. In other areas, it would mean reducing the unfairness inherent in many intellectual property laws—for example by allowing public buyout of patents for lifesaving drugs, while appropriately compensating researchers, inventors, and companies.

The completion of the American liberal project that began at Lexington and Concord requires the abolition of privilege and the extension of opportunity to all. By proving that free markets can be reconciled with passionate egalitarianism, and efficiency with justice and solidarity, Georgism can help heal our fractured republic and appeal to both sides of the political spectrum. It provides an alternative to the scarcity mindset by unleashing the productive forces of the economy, unburdened by punitive taxation. Most importantly, it can help treat the poison of populism at its root: the feeling that America doesn’t work for the average American anymore.

As George wrote in 1879:

Liberty calls to us again…Either we must wholly accept her or she will not stay. It is not enough that men should vote; it is not enough that they should be theoretically equal before the law. They must have liberty to avail themselves of the opportunities and means of life; they must stand on equal terms with reference to the bounty of nature. Either this, or Liberty withdraws her light…Unless its foundations be laid in justice, the social structure cannot stand.

—Henry George, Progress and Poverty.

Joseph Addington is the managing editor of the Substack Progress & Poverty and president of Young Georgists of America.

Follow Persuasion on Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

No comments:

Post a Comment