Climate change could return us to the pre-antibiotic era

We are in a race with ever-evolving bacteria — and we are losing. Climate change is making the battle much harder

By HOWARD DEAN

PUBLISHED JULY 12, 2024

SALON

The extreme heat that recently blanketed the United States is a clear sign of climate change. But rising temperatures are fueling more than just hotter summers. Climate change is contributing to the spread of drug-resistant infections. And alarmingly, the medicines we use to fight those pathogens are losing their effectiveness.

Antimicrobial resistance, or AMR, occurs when bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens evolve to resist the effects of medications, making common infections harder to treat and increasing the risk of disease spread, severe illness, and death. Recent figures link AMR to nearly 5 million deaths annually — far more than the combined death toll of AIDS and malaria. By 2050, more people will die of drug-resistant infections than currently die of cancer.

Related

John Kerry warns that Project 2025 would be "absolutely unimaginable and destructive" for climate reform

AMR disproportionately affects developing countries, but even in the United States, drug-resistant germs sicken nearly 3 million people and kill more than 35,000 annually. Warmer weather has led to the reemergence of diseases long absent from the United States — like dengue and West Nile virus. In my home state of Vermont, tick-borne illnesses like Lyme disease are rising as earlier springs and longer falls increase tick survival rates.

Higher temperatures also correlate strongly with greater antibiotic resistance. One study of more than 1.6 million bacterial strains collected from 41 states found that common pathogens, like E. coli, became more resistant to treatment as temperatures increased.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter Lab Notes.

The pressure cooker of climate change is moving us closer to the pre-antibiotic era. Patients I once treated as a family physician could have very different outcomes without the backstop of antibiotics. Ordinary infections could become life-threatening, and routine, minor surgeries could become high-risk procedures.

Investment in research and innovation is crucial to stay ahead of evolving pathogens. But our current efforts to develop new antibiotics are not keeping pace. There are fewer than 100 antibacterial therapies now in the pipeline, according to the World Health Organization. Just 32 of the new antibiotic candidates target priority pathogens, with only six active against high- and medium-priority pathogens.

By contrast, there are over 6,500 active clinical trials for cancer treatments.

We are in a race with ever-evolving bacteria — and we are losing. The main hurdle is financial. It costs nearly $1 billion to shepherd a new antibiotic through clinical trials.

But successfully developing an antibiotic is often financially ruinous. Most new antibiotics target small patient populations with specific drug-resistant infections, and the new medicines to treat those infections are rightly used sparingly, only as a last resort — since the more you use antibiotics, the more likely bacteria will eventually become resistant. A new antibiotic can be desperately needed, yet suffer low sales that fail to recoup extensive R&D costs. It is no wonder that just five pharmaceutical companies are currently working on new antibiotics, and many biotech firms that have developed such medicines in the past decade have gone belly up.

Combating climate change requires new technologies and new economic models. The same is true of AMR. We must rethink how we incentivize antibiotic research. Subsidies, tax credits, or direct funding for early-stage R&D can provide relief to companies developing new antibiotics. Other countries, like the United Kingdom, have experimented with subscription models, where drugmakers receive a flat fee for bringing a successful new antibiotic to market. Faster FDA approval pathways can help reduce the time and cost of clinical trials.

Ultimately, the fight against antimicrobial resistance requires a multifaceted approach, integrating scientific innovation, policy reform, and global collaboration. By addressing both climate change and AMR with the urgency and resources they demand, we can protect public health and secure a safer, healthier future for all.

Advertisement:

Read more

about this topic

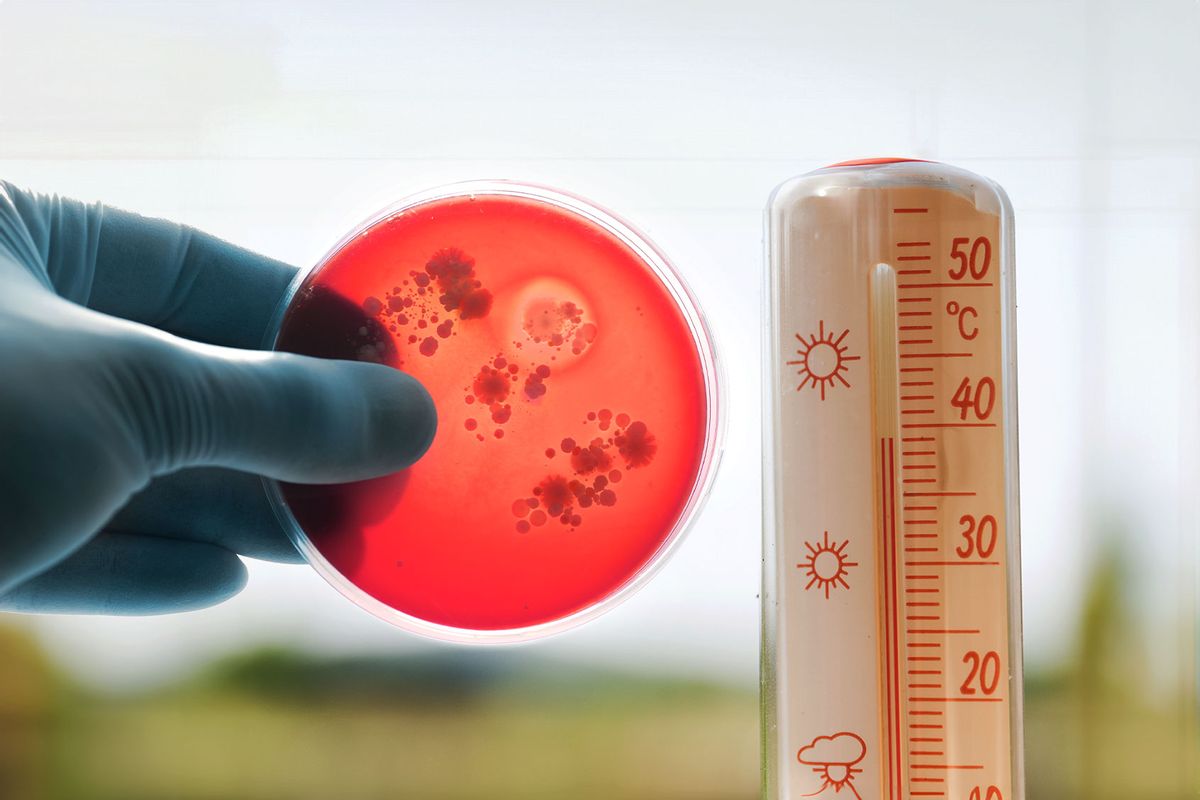

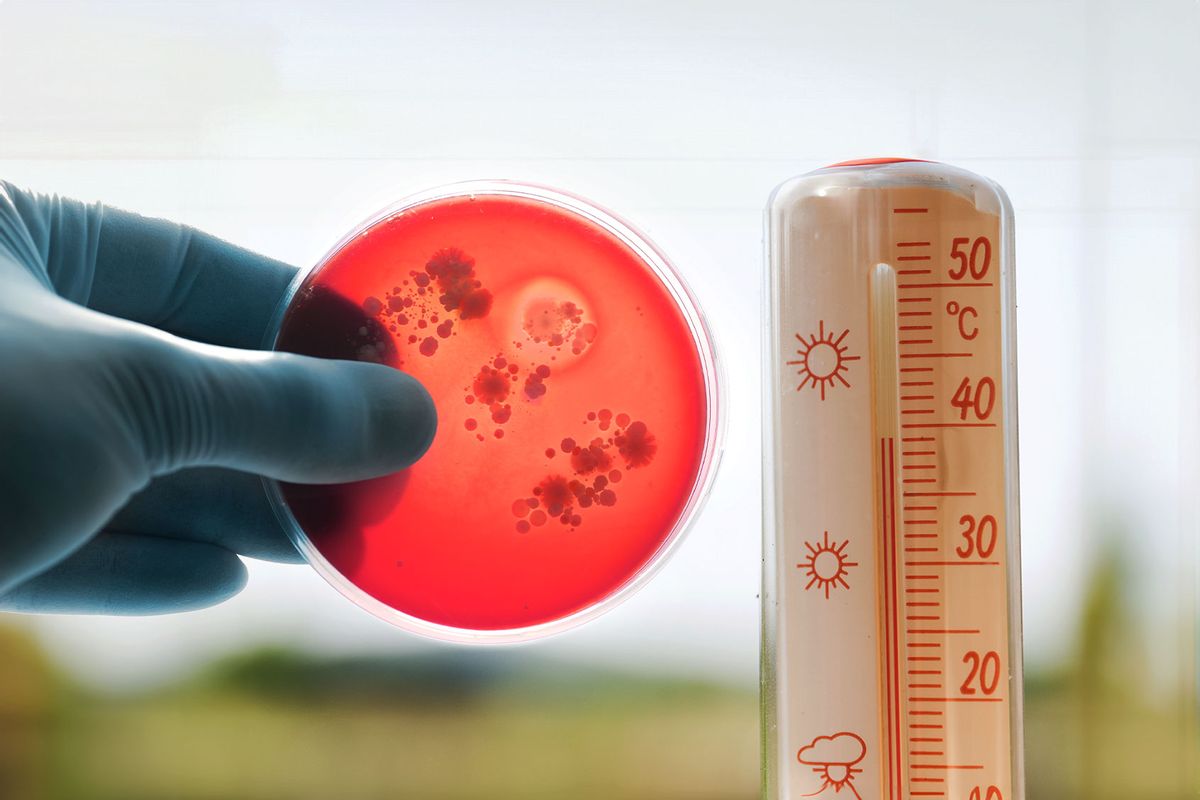

A gloved hand holding a blood agar plate with bacteria colonies grown, and a thermometer reading 39 degree Celsius. (Photo illustration by Salon/Getty Images)

The extreme heat that recently blanketed the United States is a clear sign of climate change. But rising temperatures are fueling more than just hotter summers. Climate change is contributing to the spread of drug-resistant infections. And alarmingly, the medicines we use to fight those pathogens are losing their effectiveness.

Antimicrobial resistance, or AMR, occurs when bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens evolve to resist the effects of medications, making common infections harder to treat and increasing the risk of disease spread, severe illness, and death. Recent figures link AMR to nearly 5 million deaths annually — far more than the combined death toll of AIDS and malaria. By 2050, more people will die of drug-resistant infections than currently die of cancer.

Related

John Kerry warns that Project 2025 would be "absolutely unimaginable and destructive" for climate reform

Climate change is accelerating the spread of these superbugs, providing favorable conditions for pathogens to grow and spread. Warmer temperatures can increase the reproduction rates of bacteria and viruses, extend the range of habitats suitable for pathogens, and even heighten the chances of gene transfer among bacteria, leading to more robust strains of drug-resistant microbes. Floods, hurricanes, and other climate-induced natural disasters can disrupt sanitation systems and clean water supplies. And as populations move to escape extreme weather, they often end up in over-crowded, unsanitary conditions, which become hotbeds for disease.

Warmer temperatures can increase the reproduction rates of bacteria and viruses, extend the range of habitats suitable for pathogens, and even heighten the chances of gene transfer among bacteria.

Warmer temperatures can increase the reproduction rates of bacteria and viruses, extend the range of habitats suitable for pathogens, and even heighten the chances of gene transfer among bacteria.

AMR disproportionately affects developing countries, but even in the United States, drug-resistant germs sicken nearly 3 million people and kill more than 35,000 annually. Warmer weather has led to the reemergence of diseases long absent from the United States — like dengue and West Nile virus. In my home state of Vermont, tick-borne illnesses like Lyme disease are rising as earlier springs and longer falls increase tick survival rates.

Higher temperatures also correlate strongly with greater antibiotic resistance. One study of more than 1.6 million bacterial strains collected from 41 states found that common pathogens, like E. coli, became more resistant to treatment as temperatures increased.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter Lab Notes.

The pressure cooker of climate change is moving us closer to the pre-antibiotic era. Patients I once treated as a family physician could have very different outcomes without the backstop of antibiotics. Ordinary infections could become life-threatening, and routine, minor surgeries could become high-risk procedures.

Investment in research and innovation is crucial to stay ahead of evolving pathogens. But our current efforts to develop new antibiotics are not keeping pace. There are fewer than 100 antibacterial therapies now in the pipeline, according to the World Health Organization. Just 32 of the new antibiotic candidates target priority pathogens, with only six active against high- and medium-priority pathogens.

By contrast, there are over 6,500 active clinical trials for cancer treatments.

We are in a race with ever-evolving bacteria — and we are losing. The main hurdle is financial. It costs nearly $1 billion to shepherd a new antibiotic through clinical trials.

But successfully developing an antibiotic is often financially ruinous. Most new antibiotics target small patient populations with specific drug-resistant infections, and the new medicines to treat those infections are rightly used sparingly, only as a last resort — since the more you use antibiotics, the more likely bacteria will eventually become resistant. A new antibiotic can be desperately needed, yet suffer low sales that fail to recoup extensive R&D costs. It is no wonder that just five pharmaceutical companies are currently working on new antibiotics, and many biotech firms that have developed such medicines in the past decade have gone belly up.

Combating climate change requires new technologies and new economic models. The same is true of AMR. We must rethink how we incentivize antibiotic research. Subsidies, tax credits, or direct funding for early-stage R&D can provide relief to companies developing new antibiotics. Other countries, like the United Kingdom, have experimented with subscription models, where drugmakers receive a flat fee for bringing a successful new antibiotic to market. Faster FDA approval pathways can help reduce the time and cost of clinical trials.

Ultimately, the fight against antimicrobial resistance requires a multifaceted approach, integrating scientific innovation, policy reform, and global collaboration. By addressing both climate change and AMR with the urgency and resources they demand, we can protect public health and secure a safer, healthier future for all.

Advertisement:

Read more

about this topic

Out-of-control heat is making Earth more "weird" — and more deadly

Why warzones are the perfect place for antibiotic resistance and what that means for Palestine

Turn up the heat: Climate change activists are gearing up for a sizzling summer of dissent

By Dr. HOWARD DEAN

Howard Dean is the former chair of the Democratic National Committee and former governor of Vermont.

Why warzones are the perfect place for antibiotic resistance and what that means for Palestine

Turn up the heat: Climate change activists are gearing up for a sizzling summer of dissent

By Dr. HOWARD DEAN

Howard Dean is the former chair of the Democratic National Committee and former governor of Vermont.

No comments:

Post a Comment