ABC RN /

By Nick Baker and Ian Coombe for Late Night Live

JULY12,2024

A painting that academic and writer Jonathan Schroeder believes depicts John Swanson Jacobs.(Supplied: The African American Museum in Philadelphia)

Although there were millions of men, women and children who lived and died as slaves in the US, firsthand accounts from these people are extremely rare.

"Slave narratives are such a rare document [because] there were actually laws on the books in most slave states that prohibited enslaved people from becoming literate," literary historian Jonathan Schroeder tells ABC RN's Late Night Live.

But Schroeder, a lecturer at the Rhode Island School of Design in the US city of Providence, managed to unearth one such account almost by accident.

It was written by a fugitive slave named John Swanson Jacobs, who left his homeland and started a new life on the other side of the world.

And his nearly 20,000-word life story — capped off with a searing denouncement of American slavery — was printed in a Sydney newspaper in 1855.

"The oppressor's rod shall be broken … The day must come, it will come," Jacobs wrote to his colonial Australian audience.

Now, for the first time in almost 170 years, his full 20,000-word autobiography, complete with scathing criticism of the US is being republished, thanks to Schroeder.

'No longer yours'

In the early to mid-1800s, the US was bitterly divided between the northern states that opposed slavery and the southern states that supported it.

John Swanson Jacobs was born in the southern state of North Carolina in around 1815, part of the sixth generation of his family to be enslaved.

Jacobs was sold several times, including to attorney and politician Samuel Tredwell Sawyer, who would later become a member of the US House of Representatives.

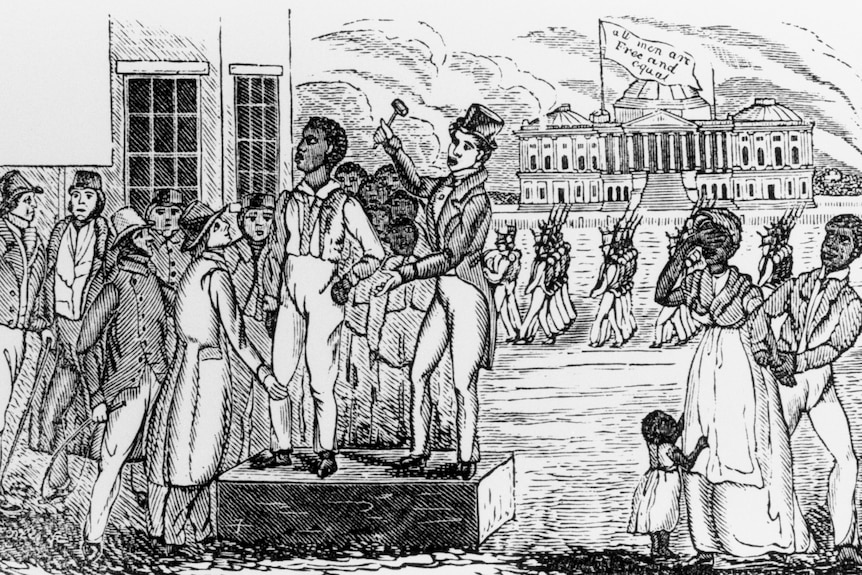

Jacobs was once sold at a slave auction, like this illustration from South Carolina.(Getty Images: Corbis)

"When you think of slaves escaping, you may think about enslaved people escaping under the cover of night, hiding in the woods, following the Moon and the North Star in order to cross … into the northern states, where slavery was abolished," Schroeder says.

"John Jacobs' escape from slavery could not be more different."

In 1838, Sawyer went on a honeymoon trip north and brought Jacobs along as his personal servant.

While in New York City, Jacobs took his chance.

He packed his bags, stole some pistols for self-defence and asked a friend to write a note, which he left in Sawyer's hotel. The note read:

"Sir — I have left you not to return; when I have got settled I will give you further satisfaction. No longer yours, John S Jacob [sic]."

Experiencing freedom for the first time, he took a boat and ended up in New Bedford, a whaling town in Massachusetts known to be a safe haven for fugitive slaves.

Leaving the US

Jacobs signed up for a job on a whaling ship and while spending years on the high seas, taught himself to read and write.

But the injustices Jacobs experienced over his lifetime could not be easily forgotten. After returning to the US, he became involved with the abolitionist movement, going on speaking tours to tell Americans directly about the horrors of slavery.

Then in 1850, US Congress passed a law called the Fugitive Slave Act. Part of a compromise between the free states in the north and the slave states in the south, it compelled all Americans on both sides of the divide to help recapture escaped slaves.

Although there were millions of men, women and children who lived and died as slaves in the US, firsthand accounts from these people are extremely rare.

"Slave narratives are such a rare document [because] there were actually laws on the books in most slave states that prohibited enslaved people from becoming literate," literary historian Jonathan Schroeder tells ABC RN's Late Night Live.

But Schroeder, a lecturer at the Rhode Island School of Design in the US city of Providence, managed to unearth one such account almost by accident.

It was written by a fugitive slave named John Swanson Jacobs, who left his homeland and started a new life on the other side of the world.

And his nearly 20,000-word life story — capped off with a searing denouncement of American slavery — was printed in a Sydney newspaper in 1855.

"The oppressor's rod shall be broken … The day must come, it will come," Jacobs wrote to his colonial Australian audience.

Now, for the first time in almost 170 years, his full 20,000-word autobiography, complete with scathing criticism of the US is being republished, thanks to Schroeder.

'No longer yours'

In the early to mid-1800s, the US was bitterly divided between the northern states that opposed slavery and the southern states that supported it.

John Swanson Jacobs was born in the southern state of North Carolina in around 1815, part of the sixth generation of his family to be enslaved.

Jacobs was sold several times, including to attorney and politician Samuel Tredwell Sawyer, who would later become a member of the US House of Representatives.

Jacobs was once sold at a slave auction, like this illustration from South Carolina.(Getty Images: Corbis)

"When you think of slaves escaping, you may think about enslaved people escaping under the cover of night, hiding in the woods, following the Moon and the North Star in order to cross … into the northern states, where slavery was abolished," Schroeder says.

"John Jacobs' escape from slavery could not be more different."

In 1838, Sawyer went on a honeymoon trip north and brought Jacobs along as his personal servant.

While in New York City, Jacobs took his chance.

He packed his bags, stole some pistols for self-defence and asked a friend to write a note, which he left in Sawyer's hotel. The note read:

"Sir — I have left you not to return; when I have got settled I will give you further satisfaction. No longer yours, John S Jacob [sic]."

Experiencing freedom for the first time, he took a boat and ended up in New Bedford, a whaling town in Massachusetts known to be a safe haven for fugitive slaves.

Leaving the US

Jacobs signed up for a job on a whaling ship and while spending years on the high seas, taught himself to read and write.

But the injustices Jacobs experienced over his lifetime could not be easily forgotten. After returning to the US, he became involved with the abolitionist movement, going on speaking tours to tell Americans directly about the horrors of slavery.

Then in 1850, US Congress passed a law called the Fugitive Slave Act. Part of a compromise between the free states in the north and the slave states in the south, it compelled all Americans on both sides of the divide to help recapture escaped slaves.

An 1850s print criticising the Fugitive Slave Act.(Getty Images: Universal History Archive)

In this changing political environment, Jacobs upended his life again. He first went to California, and then sailed for Australia with his nephew in 1852, as far away as possible from the US.

For around three years, he worked in the Australian goldfields, becoming a successful gold miner.

It's unclear exactly where he was based. But the name 'John Jacobs' — which could be this John Swanson Jacobs — appeared on an 1853 petition for miners' rights in Bendigo.

"It would make sense that he would become involved in the agitation for rights amongst the miners in Australia in the 1850s, [which] is now taken to be part of the birthplace of Australian democracy," Schroeder says.

'An unusual request'

One spring day in 1855, Jacobs walked into the office of the progressive Empire newspaper in Sydney, with what Schroeder calls "an unusual request".

He asked if he could borrow a copy of the US Constitution and a recently published history of the US

.

Sydney's George Street in 1855, where the Empire newspaper was located.(Supplied: State Library of NSW)

Jacobs returned to the newspaper office two weeks later, not only to give back the texts, but also to submit his 20,000-word autobiography, titled The United States Governed by Six Hundred Thousand Despots.

"He made an incredibly strong impression [on the newspaper staff] in part because he was a skilled orator," Schroeder says.

The Empire decided to publish the story in two 10,000-word instalments, barely altering anything other than correcting spelling and punctuation.

But for almost 170 years, Jacobs' life and his account of it were largely forgotten.

A discovery in Trove

Schroeder stumbled on Jacobs' groundbreaking story while working on another project.

"I wasn't actually looking for this text … I had no idea that it existed."

While researching another project, Schroeder had read the 1861 autobiography of well-known escaped slave Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. He'd also read the biography of Harriet Jacobs by historian Jean Fagan Yellin.

"I became fascinated by one footnote in the biography which said that Harriet Jacobs' son, Joseph Jacobs, had gone to Australia with his uncle, John S Jacobs, in 1852," he says.

A formal photograph of Harriet Jacobs — the author of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl and sister of John S Jacobs — in 1894.(Wikimedia Commons)

So Schroeder turned to Trove — the online library database owned by the National Library of Australia with billions of items, including countless Australian newspapers.

"I started searching for John S Jacobs in different spellings. And then all of a sudden, the top search result was The United States Governed by Six Hundred Thousand Despots," Schroeder says.

"What really makes [the text] so singular is the last quarter. This is not devoted to standard autobiography, but to a critique of the founding documents of the US: The Declaration of Independence, the US Constitution, and also the Fugitive Slave Act," Schroeder says.

Sydney's George Street in 1855, where the Empire newspaper was located.(Supplied: State Library of NSW)

Jacobs returned to the newspaper office two weeks later, not only to give back the texts, but also to submit his 20,000-word autobiography, titled The United States Governed by Six Hundred Thousand Despots.

"He made an incredibly strong impression [on the newspaper staff] in part because he was a skilled orator," Schroeder says.

The Empire decided to publish the story in two 10,000-word instalments, barely altering anything other than correcting spelling and punctuation.

But for almost 170 years, Jacobs' life and his account of it were largely forgotten.

A discovery in Trove

Schroeder stumbled on Jacobs' groundbreaking story while working on another project.

"I wasn't actually looking for this text … I had no idea that it existed."

While researching another project, Schroeder had read the 1861 autobiography of well-known escaped slave Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. He'd also read the biography of Harriet Jacobs by historian Jean Fagan Yellin.

"I became fascinated by one footnote in the biography which said that Harriet Jacobs' son, Joseph Jacobs, had gone to Australia with his uncle, John S Jacobs, in 1852," he says.

A formal photograph of Harriet Jacobs — the author of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl and sister of John S Jacobs — in 1894.(Wikimedia Commons)

So Schroeder turned to Trove — the online library database owned by the National Library of Australia with billions of items, including countless Australian newspapers.

"I started searching for John S Jacobs in different spellings. And then all of a sudden, the top search result was The United States Governed by Six Hundred Thousand Despots," Schroeder says.

"What really makes [the text] so singular is the last quarter. This is not devoted to standard autobiography, but to a critique of the founding documents of the US: The Declaration of Independence, the US Constitution, and also the Fugitive Slave Act," Schroeder says.

In fierce attacks, Jacobs wrote that the US Constitution was a "devil in sheepskin" and "the great chain that binds the north and south together, a union to rob and plunder the sons of Africa, a union cemented with human blood, and blackened with the guilt of 68 years".

"If a man steals my horse, he is a horse thief; but if he steals me from my mother, why is he a respectable slave holder, a member of Congress, or President of the United States?" he asked.

Jacobs named prominent politicians who had been instrumental in making compromises with slavery in the 19th century, along with savaging the slave owners, who make up the "despots" in the title.

"The direct attention to the slave owners is part of a strategy that marks this slave narrative apart from virtually all other ones," Schroeder says.

The article was published April 25, 1855.(Supplied: Trove via Jonathan Schroeder)

As for the slaves themselves? "The slave's life is a lingering death," Jacobs wrote.

"Since I cannot forget that I was a slave, I will not forget those that are slaves."

He was "eviscerating — through analysis and critique — the hypocrisy of slave-owning Americans as well as the northerners who, through inaction, were complicit with slave owners", Schroeder says.

The writing was "rhetorically gifted, unapologetically defiant prose".

'Black message, white envelope'

In 1856, Jacobs left Australia and sailed to London.

He worked various roles on ships, crisscrossing the globe from St Petersburg to Constantinople to Odessa to Bangkok.

Jacobs also published his autobiography again, at a London magazine called the Leisure Hour in 1860. But the editors of that publication cut 10,000 words, including much of his critique.

"It was burglarised. It was cut in half; tamed; sanitised," Schroeder says.

This, Schroeder says, makes the Sydney newspaper version all the more important, avoiding the "black message, white envelope" structure of some slave narratives — where white publishers would edit and repackage slave stories.

The "unfiltered" nature makes it something truly precious.

John S Jacobs' grave in Mount Auburn Cemetery, Massachusetts, marked only with the word 'brother'.(Supplied: Jonathan Schroeder)

The divide over slavery saw the US fall into civil war from 1861 to 1865, with the northern Union forces winning.

In 1872, Jacobs returned to the US, but he died shortly after that.

No comments:

Post a Comment