How Science Fiction Can Inspire Climate Activism

BY KATHERINE DOLAN

JULY 5, 2024

Photograph by Nathaniel St. Clair

Climate change is, by far, the biggest story of our era, an existential threat that has already profoundly affected life on Earth and promises to change it even more radically over the next few centuries. As our most pressing problem, it has inspired numerous non-fiction texts—news articles, science journalism, documentaries, academic monographs, and pop-science books (think Greta Thunberg’s The Climate Book or Anri Snaer Magnason’s On Time and Water).

In mainstream fiction, though, climate change took a long time to appear. In 2016, the novelist Amitav Ghosh observed in his book The Great Derangement: Climate Change and The Unthinkable that “it is a striking fact that when novelists do choose to write about climate change, it is almost always outside of fiction.”

Ghosh’s distinction between literary fiction and genre fiction implicitly discounts remarkable early treatments of climate disaster in science fiction—Laurence Manning’s The Man Who Awoke (1933), J.G. Ballard’s The Wind from Nowhere(1962) and The Drowned World (1962), George Turner’s The Sea and Summer(1987), and Octavia E. Butler’s Parable series (1993-1998), to name a few.

What’s more, at least two ‘serious’ novelists have recently tackled the subject: Margaret Atwood in her dystopian MaddAddam series (2003-2013) and Barbara Kingsolver in Flight Behavior (2012). Even so, in 2016, Ghosh’s point largely held true: Climate change was not a hugely popular subject for mainstream literary novelists.

Since then, however, more stories and novels about climate change have been published and are attracting recognition. Ghosh himself marks the turning point as 2018, a year that saw a wave of extreme climate events, and the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction going to Richard Powers for The Overstory (2018), a book that foregrounds the usually invisible world of trees.

What Is Cli-Fi?

Cli-fi encompasses narratives about climate change. The tag was first coined by journalist and climate activist Dan Bloom, who used it in print in a review of Jim Laughter’s 2012 novella Polar City Red.

As the rhyme suggests, cli-fi is a sub-genre of sci-fi. It tends to be speculative, to focus on anthropogenic global warming, and to examine the effects of climate change on human communities. Frequently, as with Atwood’s trilogy, there is a dystopian slant.

In keeping with the complexity of climate change itself, cli-fi is multiform, encompassing science fiction, fantasy, mystery, thriller, magical realism, fable, satire, and everything in between.

Speculative works set in the future in a world where climate change has already transformed the Earth offer models of possibility and cautionary tales. Bangkok Wakes to Rain (2020) by Pitchaya Sudbanthad takes place in the Thai capital in the late twenty-first century when the city is submerged by the rising sea. American Warby Omar el Akkad is set in 2074 when a ban on the sale of fossil fuels ignites a new American Civil War. Similarly, Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Water Knife (2016) imagines a near future in which the Colorado River drying up leads to bloodshed.

Many books foreground the human cost of climate change rather than explaining its scientific basis. Salvage the Bones (2011) by Jesmyn Ward, for example, describes a family drama in the lead-up to Hurricane Katrina, a storm whose intensity presaged the increasingly destructive storms caused by climate change. How Beautiful We Were (2021) by Imbolo Imbue takes a different approach, showing African villagers standing up to a big American oil company, and The Book of Fire (2023) by Christy Leftieri traces the tragic aftermath of a wildfire in present-day Greece.

Some novels offer elegiac depictions of climate change’s costs to other species. These include Migrations (2020) and Once There Were Wolves (2021) by Charlotte McConaghy, The Effort (2021) by Claire Holroyde, and Hummingbird Salamander(2021) by Jeff VanderMeer. Science historian Daisy Hildyard privileges nature’s perspective in Emergency (2024), her novel about the interconnectedness of life.

A growing theme is familiar to many of us: climate anxiety, the psychological toll of waiting for the end of the world as we know it. Weather by Jenny Offill (2020) is centered firmly on the day-to-day life of a Brooklyn woman who must carry out her usual tasks with the threat of climate change always looming in the background.

Why We Need Fiction About Climate Change

In an interview with author David Thorpe, Dan Bloom pointed out that fiction can express what cold facts can not:

“We need to go beyond abstract, scientific predictions and government statistics and try to show the cinematic or literary reality of a painful, possible future of the world of climate change. I do believe that cli-fi is a veritable cultural prism, a powerful critical prism that we need to cherish and nurture among our artists and visionary storytellers.”

In 2019, climate writer Dominic Hofstetter asked former European commissioner for Climate Action Connie Hedegaard what it would take for humanity to get serious about our common plight. Hedegaard’s reply was simple: “We need compelling narratives.”

Bluntly, storytelling is the best way—maybe the only way—to inform, persuade, and inspire people to act. It helps us assimilate facts, contextualize them, and understand and share their meaning. A good story moves us emotionally, allowing us to register its import “in our gut.” As author and story coach Lisa Cron, author of Story or Die, says, “We don’t turn to story to escape reality; we turn to story to navigate reality.”

An engaging story is not just persuasive; it also has the potential to build community. A Princeton University study revealed that when a group of people listened to an emotionally engaging story, their brain activity synchronized during the telling—as a group, they imagined the same world and felt the same emotions.

Barbara Kingsolver, speaking of her book Flight Behavior (2012), explained why fiction, in particular, is valuable as a medium for communicating urgent environmental issues:

“Fiction has enormous power. It’s funny—people talk about political fiction or apolitical fiction. That’s nonsense. I think all fiction has a point of view, and all fiction has the power to create empathy for the theoretical stranger. It has the power to bring the reader inside the mind of another person. Only fiction can do that.”

For author, psychologist, and futurist Dana Klisanin, author of the young-adult novel Future Hack, stories are a way to travel to a different universe:

“I was an avid reader as a child. Even when I was told to turn off the light and go to sleep, I would grab a flashlight and hide under the bed covers to finish a story. In other words, I was completely absorbed in the world of the book.”

This experience, familiar to many of us, is known to scientists as “narrative transportation,” which happens when readers assume the thoughts and feelings of a character and when they mentally simulate a narrative world.

In Klisanin’s words:

“This deep engagement leads to greater absorption and enjoyment and can profoundly impact the reader’s attitudes and behaviors, making the lessons from the story more likely to be internalized. High narrative transportation has also been shown to enhance empathy, supporting understanding and connection with the emotions and experiences of others.”

Considering its influence on attitudes and actions, storytelling has the potential to make an outsized impact on things like community engagement, and many governments and organizations are starting to pay attention to this.

In 2017, the American Public Health Association (APHA) launched an initiative encouraging people to share personal stories about how climate-related events affected their health and what actions they or their community took to address the situation. The idea was to build a sense of community, resilience, and hope. According to an APHA guide to storytelling:

“Stories make climate change relatable by drawing on common experience and core human values, like health. Compelling stories generate empathy and understanding. They take listeners on an emotional journey and offer a sense of hope that inspires positive change.”

Visions of Hope

The most important emotion fiction can inspire is a sense of hope, a necessary factor for climate activists working toward the best possible outcomes in the face of impending catastrophe.

In an interview with NPR, Imbue says she derived the hopeful aspect of her protagonist Tula from the writing of revolutionary figures like Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr.:

“I mean, you have to have a whole different level of hope to believe that you can bring an American oil company to justice, an American oil company that has resources and lawyers and all kinds of powers at its disposal. But Tula does believe that. And that is something that I learned from reading, from looking at their lives.”

Another hopeful cli-fi writer is Kim Stanley Robinson, who weaves scientific findings into a compelling narrative. A prime example is his bestselling The Ministry for the Future (2020), which posits a body whose political mission is to advocate for the people of the future. Responding to a description of the work as a utopian novel, he welcomes the judgment:

“You could probably name the most important utopian novels on the fingers of your hand. …But they get remembered, and they shape people’s conception of what’s possible that could be good in the future.”

Klisanin has a similarly positive yet realistic view. Her novel Future Hack features young characters who face climate-related problems with boundless energy and a problem-solving spirit. Her intention is to reassure and inspire confidence. Klisanin wrote:

“I hope that Future Hack will inspire readers with a sense of hope and possibility for the future and embolden them to take action to protect the environment and endangered species. As the series unfolds, I also aim to help readers struggling with eco-anxiety by showing them that they are not alone and by introducing them to some coping methods.”

The climate crisis has not yet generated a single written work as powerful as Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962) was in mobilizing mid-twentieth-century audiences against DDT and other toxic chemicals. But we can at least be cheered by the number of talented writers who, in varied ways and multiple genres, are working to produce such a story.

This article was produced by Earth | Food | Life, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Katherine Dolan is a writer, editor, and researcher at the Independent Media Institute from Dunedin, New Zealand. Dolan is a former senior writer at Fairfax Media Custom Publishing in New Zealand, Lifestyle Magazine in Moscow, and a copy editor for the U.S. news site NSFWCORP. She is a contributor to the Observatory.

JULY 5, 2024

Photograph by Nathaniel St. Clair

Climate change is, by far, the biggest story of our era, an existential threat that has already profoundly affected life on Earth and promises to change it even more radically over the next few centuries. As our most pressing problem, it has inspired numerous non-fiction texts—news articles, science journalism, documentaries, academic monographs, and pop-science books (think Greta Thunberg’s The Climate Book or Anri Snaer Magnason’s On Time and Water).

In mainstream fiction, though, climate change took a long time to appear. In 2016, the novelist Amitav Ghosh observed in his book The Great Derangement: Climate Change and The Unthinkable that “it is a striking fact that when novelists do choose to write about climate change, it is almost always outside of fiction.”

Ghosh’s distinction between literary fiction and genre fiction implicitly discounts remarkable early treatments of climate disaster in science fiction—Laurence Manning’s The Man Who Awoke (1933), J.G. Ballard’s The Wind from Nowhere(1962) and The Drowned World (1962), George Turner’s The Sea and Summer(1987), and Octavia E. Butler’s Parable series (1993-1998), to name a few.

What’s more, at least two ‘serious’ novelists have recently tackled the subject: Margaret Atwood in her dystopian MaddAddam series (2003-2013) and Barbara Kingsolver in Flight Behavior (2012). Even so, in 2016, Ghosh’s point largely held true: Climate change was not a hugely popular subject for mainstream literary novelists.

Since then, however, more stories and novels about climate change have been published and are attracting recognition. Ghosh himself marks the turning point as 2018, a year that saw a wave of extreme climate events, and the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction going to Richard Powers for The Overstory (2018), a book that foregrounds the usually invisible world of trees.

What Is Cli-Fi?

Cli-fi encompasses narratives about climate change. The tag was first coined by journalist and climate activist Dan Bloom, who used it in print in a review of Jim Laughter’s 2012 novella Polar City Red.

As the rhyme suggests, cli-fi is a sub-genre of sci-fi. It tends to be speculative, to focus on anthropogenic global warming, and to examine the effects of climate change on human communities. Frequently, as with Atwood’s trilogy, there is a dystopian slant.

In keeping with the complexity of climate change itself, cli-fi is multiform, encompassing science fiction, fantasy, mystery, thriller, magical realism, fable, satire, and everything in between.

Speculative works set in the future in a world where climate change has already transformed the Earth offer models of possibility and cautionary tales. Bangkok Wakes to Rain (2020) by Pitchaya Sudbanthad takes place in the Thai capital in the late twenty-first century when the city is submerged by the rising sea. American Warby Omar el Akkad is set in 2074 when a ban on the sale of fossil fuels ignites a new American Civil War. Similarly, Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Water Knife (2016) imagines a near future in which the Colorado River drying up leads to bloodshed.

Many books foreground the human cost of climate change rather than explaining its scientific basis. Salvage the Bones (2011) by Jesmyn Ward, for example, describes a family drama in the lead-up to Hurricane Katrina, a storm whose intensity presaged the increasingly destructive storms caused by climate change. How Beautiful We Were (2021) by Imbolo Imbue takes a different approach, showing African villagers standing up to a big American oil company, and The Book of Fire (2023) by Christy Leftieri traces the tragic aftermath of a wildfire in present-day Greece.

Some novels offer elegiac depictions of climate change’s costs to other species. These include Migrations (2020) and Once There Were Wolves (2021) by Charlotte McConaghy, The Effort (2021) by Claire Holroyde, and Hummingbird Salamander(2021) by Jeff VanderMeer. Science historian Daisy Hildyard privileges nature’s perspective in Emergency (2024), her novel about the interconnectedness of life.

A growing theme is familiar to many of us: climate anxiety, the psychological toll of waiting for the end of the world as we know it. Weather by Jenny Offill (2020) is centered firmly on the day-to-day life of a Brooklyn woman who must carry out her usual tasks with the threat of climate change always looming in the background.

Why We Need Fiction About Climate Change

In an interview with author David Thorpe, Dan Bloom pointed out that fiction can express what cold facts can not:

“We need to go beyond abstract, scientific predictions and government statistics and try to show the cinematic or literary reality of a painful, possible future of the world of climate change. I do believe that cli-fi is a veritable cultural prism, a powerful critical prism that we need to cherish and nurture among our artists and visionary storytellers.”

In 2019, climate writer Dominic Hofstetter asked former European commissioner for Climate Action Connie Hedegaard what it would take for humanity to get serious about our common plight. Hedegaard’s reply was simple: “We need compelling narratives.”

Bluntly, storytelling is the best way—maybe the only way—to inform, persuade, and inspire people to act. It helps us assimilate facts, contextualize them, and understand and share their meaning. A good story moves us emotionally, allowing us to register its import “in our gut.” As author and story coach Lisa Cron, author of Story or Die, says, “We don’t turn to story to escape reality; we turn to story to navigate reality.”

An engaging story is not just persuasive; it also has the potential to build community. A Princeton University study revealed that when a group of people listened to an emotionally engaging story, their brain activity synchronized during the telling—as a group, they imagined the same world and felt the same emotions.

Barbara Kingsolver, speaking of her book Flight Behavior (2012), explained why fiction, in particular, is valuable as a medium for communicating urgent environmental issues:

“Fiction has enormous power. It’s funny—people talk about political fiction or apolitical fiction. That’s nonsense. I think all fiction has a point of view, and all fiction has the power to create empathy for the theoretical stranger. It has the power to bring the reader inside the mind of another person. Only fiction can do that.”

For author, psychologist, and futurist Dana Klisanin, author of the young-adult novel Future Hack, stories are a way to travel to a different universe:

“I was an avid reader as a child. Even when I was told to turn off the light and go to sleep, I would grab a flashlight and hide under the bed covers to finish a story. In other words, I was completely absorbed in the world of the book.”

This experience, familiar to many of us, is known to scientists as “narrative transportation,” which happens when readers assume the thoughts and feelings of a character and when they mentally simulate a narrative world.

In Klisanin’s words:

“This deep engagement leads to greater absorption and enjoyment and can profoundly impact the reader’s attitudes and behaviors, making the lessons from the story more likely to be internalized. High narrative transportation has also been shown to enhance empathy, supporting understanding and connection with the emotions and experiences of others.”

Considering its influence on attitudes and actions, storytelling has the potential to make an outsized impact on things like community engagement, and many governments and organizations are starting to pay attention to this.

In 2017, the American Public Health Association (APHA) launched an initiative encouraging people to share personal stories about how climate-related events affected their health and what actions they or their community took to address the situation. The idea was to build a sense of community, resilience, and hope. According to an APHA guide to storytelling:

“Stories make climate change relatable by drawing on common experience and core human values, like health. Compelling stories generate empathy and understanding. They take listeners on an emotional journey and offer a sense of hope that inspires positive change.”

Visions of Hope

The most important emotion fiction can inspire is a sense of hope, a necessary factor for climate activists working toward the best possible outcomes in the face of impending catastrophe.

In an interview with NPR, Imbue says she derived the hopeful aspect of her protagonist Tula from the writing of revolutionary figures like Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr.:

“I mean, you have to have a whole different level of hope to believe that you can bring an American oil company to justice, an American oil company that has resources and lawyers and all kinds of powers at its disposal. But Tula does believe that. And that is something that I learned from reading, from looking at their lives.”

Another hopeful cli-fi writer is Kim Stanley Robinson, who weaves scientific findings into a compelling narrative. A prime example is his bestselling The Ministry for the Future (2020), which posits a body whose political mission is to advocate for the people of the future. Responding to a description of the work as a utopian novel, he welcomes the judgment:

“You could probably name the most important utopian novels on the fingers of your hand. …But they get remembered, and they shape people’s conception of what’s possible that could be good in the future.”

Klisanin has a similarly positive yet realistic view. Her novel Future Hack features young characters who face climate-related problems with boundless energy and a problem-solving spirit. Her intention is to reassure and inspire confidence. Klisanin wrote:

“I hope that Future Hack will inspire readers with a sense of hope and possibility for the future and embolden them to take action to protect the environment and endangered species. As the series unfolds, I also aim to help readers struggling with eco-anxiety by showing them that they are not alone and by introducing them to some coping methods.”

The climate crisis has not yet generated a single written work as powerful as Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962) was in mobilizing mid-twentieth-century audiences against DDT and other toxic chemicals. But we can at least be cheered by the number of talented writers who, in varied ways and multiple genres, are working to produce such a story.

This article was produced by Earth | Food | Life, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Katherine Dolan is a writer, editor, and researcher at the Independent Media Institute from Dunedin, New Zealand. Dolan is a former senior writer at Fairfax Media Custom Publishing in New Zealand, Lifestyle Magazine in Moscow, and a copy editor for the U.S. news site NSFWCORP. She is a contributor to the Observatory.

Extreme flooding in Germany caused roads and railways to be cut off. Bear productions/Shutterstock

THE CONVERSATION

Published: February 9, 2022

Smog-ridden cities. Endless war. Water so polluted it cannot be drunk. Crop failure. Acid rain. A pandemic of antibiotic-resistant diseases. Declining life expectancy and human fertility. Endangered bees, collapsing agriculture. Mass extinctions have finished off most birds and fish. Only the wealthiest can afford quality organic food, while the poor subsist on lab-produced junk (with added tranquilisers). A celebrity president peddles misinformation in tweet-like slogans. A disillusioned academic tries in vain to bring about change, while his followers block roads and resort to terrorism.

This is not a bad dream version of recent climate change headlines. This is the dark vision in the 50-year-old dystopian novel, The Sheep Look Up, by John Brunner. A British author, Brunner was one of a handful of writers who were early advocates of environmental activism.

No more heroes

Experimental in style, bleak in outlook, the novel is short on heroes and villains. The chapters follow 12 months in which the United States gradually collapses as unrestricted pollution wipes out the water and food supply. Some of its best lines go to Austin Train, an environmentalist who attempts to persuade others that that they must act now to protect human life. But throughout the novel he is mostly ignored.

The book is a reminder that the courage of activists such as Greta Thunberg and Vanessa Nakate should not be ridiculed or ignored, but celebrated for speaking truth to power. All of us must heed their warnings and act now to reduce our impact on global heating. Western countries have become too dependent on outsourcing our pollution to far away lands. It’s time to stop outsourcing our dissent.

Read more: Plants are flowering a month earlier – here's what it could mean for pollinating insects

Failure to act

Brunner wrote his novel the same year that the Club of Rome, an international group of policymakers, economists and business leaders, published their influential report The Limits to Growth. Using computer projections, it warned that the planet lacked the resources to sustain current projections of human consumption and growth.

Fiction’s influencers

Some early readers drew a bleak analysis that environmental activism was futile, but many read it as a call to action. Brunner used sci-fi as a form of social and political criticism, something that was fairly new at the time.

Abstract projections about emissions, droughts and pollutions can be hard to grasp. But research shows that fictional narratives and metaphors have a significant role in helping us understand complex social issues.

Storytelling helps us recognise the consequences of our decisions to act or not act, as we follow the impact of choices made by characters.

Around the world, psychologists and clinicians are now observing a condition called “climate anxiety” or “eco-anxiety”. As the name suggests, it’s marked by anxiety, panic attacks, depression and feelings of anger and betrayal. A recent global survey of 10,000 young people found that 75% felt that the future was frightening and that 59% were very or extremely worried about climate change.

But what some researchers and campaigners have also found is that anxiety reduces when people get together and focus on collective action.

Great storytelling is all about revealing the choices that lie before us. And this is all part of Brunner’s technique. It connects the great 20th-century dystopias of George Orwell and Aldous Huxley to the modern-day climate fiction of Margaret Atwood and Amitav Ghosh.

What next?

Brunner’s dire predictions have not completely come to pass. Clearly there have been dramatic and dangerous environmental changes, but also steps forward in knowledge. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the United Nations Environment Programme, and the 30th anniversary of the Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit.

There have been some important achievements in curbing pollution, from the Montreal Protocol to the 2015 Paris Agreement. And around the world, voices young and old are now demanding urgent, systemic change, something that might have surprised Brunner.

Published: February 9, 2022

Smog-ridden cities. Endless war. Water so polluted it cannot be drunk. Crop failure. Acid rain. A pandemic of antibiotic-resistant diseases. Declining life expectancy and human fertility. Endangered bees, collapsing agriculture. Mass extinctions have finished off most birds and fish. Only the wealthiest can afford quality organic food, while the poor subsist on lab-produced junk (with added tranquilisers). A celebrity president peddles misinformation in tweet-like slogans. A disillusioned academic tries in vain to bring about change, while his followers block roads and resort to terrorism.

This is not a bad dream version of recent climate change headlines. This is the dark vision in the 50-year-old dystopian novel, The Sheep Look Up, by John Brunner. A British author, Brunner was one of a handful of writers who were early advocates of environmental activism.

No more heroes

Experimental in style, bleak in outlook, the novel is short on heroes and villains. The chapters follow 12 months in which the United States gradually collapses as unrestricted pollution wipes out the water and food supply. Some of its best lines go to Austin Train, an environmentalist who attempts to persuade others that that they must act now to protect human life. But throughout the novel he is mostly ignored.

The book is a reminder that the courage of activists such as Greta Thunberg and Vanessa Nakate should not be ridiculed or ignored, but celebrated for speaking truth to power. All of us must heed their warnings and act now to reduce our impact on global heating. Western countries have become too dependent on outsourcing our pollution to far away lands. It’s time to stop outsourcing our dissent.

Read more: Plants are flowering a month earlier – here's what it could mean for pollinating insects

Failure to act

Brunner wrote his novel the same year that the Club of Rome, an international group of policymakers, economists and business leaders, published their influential report The Limits to Growth. Using computer projections, it warned that the planet lacked the resources to sustain current projections of human consumption and growth.

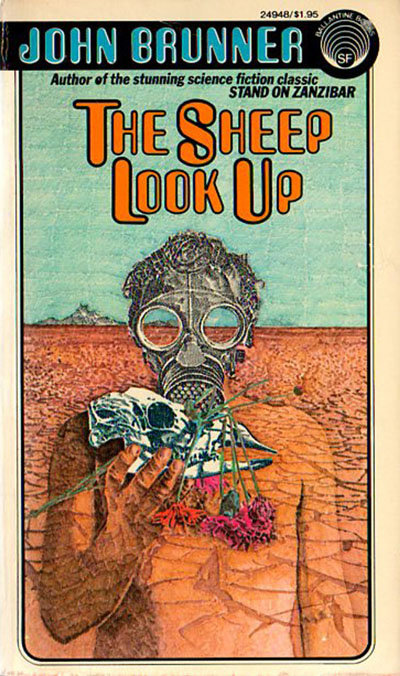

The cover of sci-fi climate classic The Sheep Look Up.

Cover by Mark Rubin and Irving Freeman., CC BY

From the early 1960s there were signs that human activity was starting to be linked to environmental damage. Author Rachel Carson wrote her acclaimed Silent Spring in 1962 – and in 1965 the US science advisory committee report wrote to US president, Lyndon Johnson, about the dangers of air pollution.

Brunner was surprised that more people weren’t alarmed. The Sheep Look Up warns about what happens when people fail to act against an unfolding catastrophe. While the present might be endurable, the future will not be, as demonstrated in the recent scenarios forecast in the most recent IPCC report.

As one of Brunner’s characters observed: “This is the future, unless we prevent it.”

From the early 1960s there were signs that human activity was starting to be linked to environmental damage. Author Rachel Carson wrote her acclaimed Silent Spring in 1962 – and in 1965 the US science advisory committee report wrote to US president, Lyndon Johnson, about the dangers of air pollution.

Brunner was surprised that more people weren’t alarmed. The Sheep Look Up warns about what happens when people fail to act against an unfolding catastrophe. While the present might be endurable, the future will not be, as demonstrated in the recent scenarios forecast in the most recent IPCC report.

As one of Brunner’s characters observed: “This is the future, unless we prevent it.”

Fiction’s influencers

Some early readers drew a bleak analysis that environmental activism was futile, but many read it as a call to action. Brunner used sci-fi as a form of social and political criticism, something that was fairly new at the time.

Abstract projections about emissions, droughts and pollutions can be hard to grasp. But research shows that fictional narratives and metaphors have a significant role in helping us understand complex social issues.

Storytelling helps us recognise the consequences of our decisions to act or not act, as we follow the impact of choices made by characters.

Around the world, psychologists and clinicians are now observing a condition called “climate anxiety” or “eco-anxiety”. As the name suggests, it’s marked by anxiety, panic attacks, depression and feelings of anger and betrayal. A recent global survey of 10,000 young people found that 75% felt that the future was frightening and that 59% were very or extremely worried about climate change.

But what some researchers and campaigners have also found is that anxiety reduces when people get together and focus on collective action.

Great storytelling is all about revealing the choices that lie before us. And this is all part of Brunner’s technique. It connects the great 20th-century dystopias of George Orwell and Aldous Huxley to the modern-day climate fiction of Margaret Atwood and Amitav Ghosh.

What next?

Brunner’s dire predictions have not completely come to pass. Clearly there have been dramatic and dangerous environmental changes, but also steps forward in knowledge. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the United Nations Environment Programme, and the 30th anniversary of the Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit.

There have been some important achievements in curbing pollution, from the Montreal Protocol to the 2015 Paris Agreement. And around the world, voices young and old are now demanding urgent, systemic change, something that might have surprised Brunner.

No comments:

Post a Comment