A collection of more than a dozen people’s history stories from July 4th beyond 1776. The stories include July 4th anniversaries such as when slavery was abolished in New York (1827), Frederick Douglass’s speech “The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro” (1852), the Reconstruction era attack on a Black militia that led to the Hamburg Massacre (1876), protest of segregation at an amusement park in Baltimore (1963), and more.

1827: Slavery Abolished in New York.

On July 4, 1827, slavery was abolished in New York, following a gradual emancipation law

that went into effect in 1799. However, as historian James Horton explains in a PBS interview, New York continued to benefit economically from the system of human bondage. “New York really provided much of the capital that made the plantation economy in the South possible.”

Learn more in these two resources by Alan Singer, the book New York and Slavery: Time to Teach the Truth and an article, “Reclaiming Hidden History: Students Create a Slavery Walking Tour in Manhattan” about how he and his students organized a tour of the hidden history of slavery in New York.

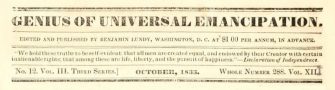

1831: William Watkins Speaks for Black Americans on Independence Day

William Watkins wrote an “Independence Day” lamentation and reflection for Black Americans under the penname of “A Colored Baltimorean” on July 4, 1831 (published in the Genius of Universal Emancipation):

On this great festival of civil and religious liberty, while ten millions of freemen are celebrating in “festive songs of joy” the magnanimous achievements of the “departed great” . . . while they are proclaiming in tones of thunder, from centre to circumference of this widespread Union, the “self-evident truths,” that all men are created equal, and endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights . . . I, feeling the injustice done me by the laws of my country, retired from the exulting multitude . . . to contemplate the past and the present as connected with our history in the land our nativity.

Johns Hopkins University professor Martha Jones, PhD, writes that “It was a moment filled with despair and hope in equal measure. His despair was a response to the rise of a colonization movement and Black laws — schemes aimed at so degrading the lives of former slaves that they would seek refuge in Liberia, Canada, or the Caribbean. Watkins’ hope was rooted in a budding social movement, that of abolitionism. There, he found seeds of a radical vision that might remake the place of Black people within the United States.”

Watkins was born a free Black man in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1826. A cousin of the famous writer Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, he was deeply involved in the northern abolitionist movement and a contemporary of Frederick Douglass. William Watkins advocated for school integration and a Black militia during the slavery era, and in 1865 he became one of the first Black lawyers in the United States. (Paraphrased. Source: The Colored Conventions.)

1833: Mohegan William Apess Jailed for Defense of Native Land

William Apess, Mohegan revolutionary and author, worked with the Wampanoag to defend their rights. They would lead what would be called the Mashpee Revolt in 1833 to address the wood poaching issue in their forest.

They posted signs declaring it their land. They also petitioned Harvard for the reclamation of their meetinghouse. They exposed Harvard’s missionary, the Reverand Phineas Fish, as exploiting the land he was allotted as part of his religious work and demanded he be removed from his post.

They enforced their petition regarding wood poaching peacefully. On July 1, 1833, they unloaded settlers’ wagons that were taking wood. The local government arrested Apess and his companions on July 4. They were charged with ‘riot, assault,’ and ‘trespassing’ (on their own community land). They received sympathy and support from some including the Barnstable Journal. The Journal published the Wampanoag men’s own words that compared the ‘Mashpee Revolt’ to the American Revolution saying, “We unloaded two wagons of wood” in place of “English ships of tea.” Excerpted from Native News Online (page currently unavailable).

Jeff Biggers explains in Resistance: Reclaiming an American Tradition that Apess disregarded the charges. “The laws ought to be altered without delay, that it was perfectly manifest they were unconstitutional. In my mind, it was no punishment at all and I am yet to learn what punishment can dismay a man conscious of his own innocence. Lightning, tempest, and battle, wreck, pain, buffeting, and torture have small terror to a pure conscience.” In a dramatic act of nonviolent civil disobedience, Apess remained in jail for several days, gambling that the attention to the Mashpee revolt would gain broader support. Harvard students, including Henry David Thoreau, would take note of Apess’s forewarning words of resistance; the controversial Harvard-appointed minister to Mashpee would eventually be replaced. Read more about William Apess in Resistance: Reclaiming an American Tradition.

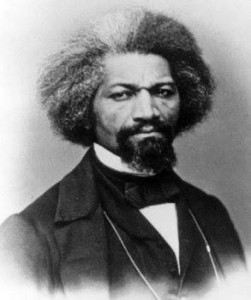

July 5, 1852: Frederick Douglass Delivered “The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro” Speech

In 1852, abolitionist Frederick Douglass delivered his speech “The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro,” on July 5 at an event commemorating the signing of the Declaration of Independence in Rochester, New York. Douglass’ words resonate today.

The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity, and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony.

See Danny Glover read from this speech (part of The People Speak series) and explore teaching resources on Frederick Douglass at the Zinn Education Project.

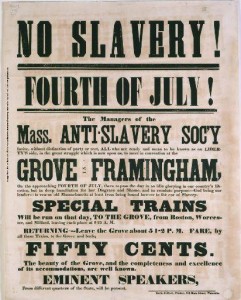

1854: Abolitionists Addressed Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society Rally

Broadside advertising a Fourth of July rally sponsored by the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society in 1854.

On July 4, 1854, abolitionists — including William Lloyd Garrison, Sojourner Truth, Lucy Stone, and Henry David Thoreau — addressed a rally sponsored by the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society.

At the rally, Garrison burned copies of the Fugitive Slave Act and the U.S. Constitution, crying out “So perish all compromises with tyranny!” This referred to two recent incidents: the passing of the Kansas-Nebraska Act into law on May 30, which expanded slavery into these territories; and the arrest and the re-enslavement of Anthony Burns who had been taken into custody on May 24 in Boston, in compliance with the Fugitive Slave Act, a component of the Compromise of 1850. Read a detailed description about the rally at the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Use the teaching activity, ‘If There Is No Struggle. . .’: Teaching a People’s History of the Abolition Movement, where students become members of the American Anti-Slavery Society, facing many of the real challenges to ending slavery.

1876: Suffragists Crashed Centennial Celebration at Independence Hall to Present the “Declaration of the Rights of Women”

Four of five women who delivered the declaration: (L-R) Matilda Joslyn Gage, Lillie Devereux Blake, Susan B. Anthony, and Phoebe Couzins.

On July 4, 1876, 100 years after the signing of the Declaration of Independence, members of the National Woman Suffrage Association crashed the Centennial Celebration at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to present the “Declaration of the Rights of Women.” The declaration was signed by noted suffragists Susan B. Anthony, Matilda Joslyn Gage, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Read more about this at event at Ms. Magazine and read the full document at the Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony Papers Project.

Explore an earlier period of the women’s suffrage movement in “Seneca Falls, 1848: Women Organize for Equality,” a role play that allows students to examine issues of race and class when exploring both the accomplishments and limitations of the Seneca Falls Convention.

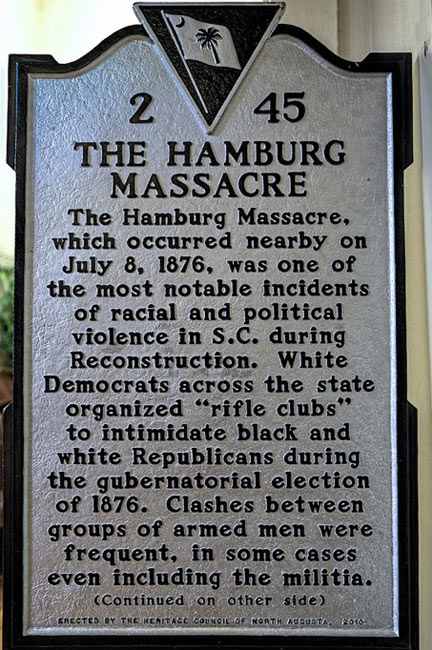

1876: Black Militia Accused of Blocking Road — Punished with Hamburg Massacre

On July 4, 1876, (in the midst of a heated Reconstruction era local election season) a Black militia was engaged in military exercises when two white farmers attempted to drive through.

Although the farmers got through the military formation after an initial argument, this event provided the excuse sought by whites to suppress Black voting through violence.

On July 6, in a courtroom, the farmers charged the militia with obstructing the road.

The case was postponed to July 8, by which time more than 100 whites from local counties had gathered in town, armed with weapons. The African Americans attempted to flee, but 25 men were captured and six were murdered.

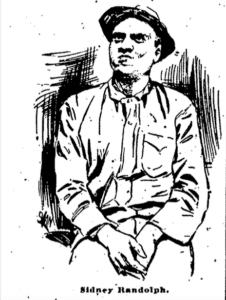

1896: Sidney Randolph Was Lynched in Maryland

Sidney Randolph, a native of Georgia in his mid-twenties, was lynched in Rockville, Maryland on July 4, 1896 by an officially-unidentified group of white men from Montgomery County.

According to journalist and activist Ida B. Wells, who had spent the previous five years researching lynchings throughout the South, Randolph’s murder fell in line with many typical lynch law actions she had observed against Black men. In a speech given to the Anti-Lynching Society in Washington, D.C. a few weeks after his murder, she said, “Many a negro is lynched as a scapegoat for another man’s crime. An editorial in one of the papers clearly states that the lynching of Sidney Randolph, the negro lynched in Montgomery County, Md, was instigated by the real murderer of Sadie Buxton. Randolph was a scapegoat.” [This text is by Sarah Hedlund, archivist/librarian and reprinted from Montgomery History, 2021. Read in full.]

1910: Jack Johnson Defeats James J. Jeffries

On July 4, 1910, African American heavyweight champion Jack Johnson successfully defended his title by knocking out James J. Jeffries, who had come out of retirement “to win back the title for the White race” in Reno, Nevada.

Terrorist attacks were made on Africans Americans (referred to in media and textbooks as “race riots”) throughout the country that evening and on July 5.

See articles and primary documents about the fight from the Library of Congress’ Chronicling America series.

Learn more in A People’s History of Sports in the United States by Dave Zirin.

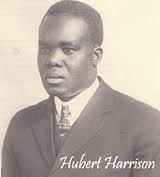

1917: The Voice: A Newspaper for the New Negro Made its Debut

On July 4, 1917, The Voice: A Newspaper for the New Negro — the first newspaper of the “New Negro Movement,” edited by Hubert H. Harrison — made its debut at a rally held at the Metropolitan Baptist Church in Harlem. Referring to the massacre the day before of African Americans in St. Louis, Harrison reportedly said, “They are saying a great deal about democracy in Washington now,” but, “while they are talking about fighting for freedom and the Stars and Stripes, here at home the whites apply the torch to the Black men’s homes, and bullets, clubs and stones to their bodies.” [Editors note: These words may have been by another speaker at the rally.] Read more in “Hubert Harrison Urges Armed Self-Defense at Harlem Rally” by Jeffrey Perry.

Learn more about the history of media in the United States, through the lens of race, in the book News for All the People: The Epic Story of Race and the American Media by Juan González and Joseph Torres.

1919: Black Soldiers Attacked While Preparing for Independence Day Parade

On July 3, 1919, active members of the Army’s segregated 10th Cavalry Regiment (“Buffalo Soldiers”) were in Bisbee, Arizona, to participate in the town’s Independence Day parade. With tensions high and discrimination rampant, it is not surprising that a fight broke out between a white policeman and a handful of Black soldiers in Brewery Gulch.

According to a New York Times report about the violence in Bisbee, local white law enforcement “planned deliberately to aggravate the Negro troops so that they would furnish an excuse for police and deputy sheriffs to shoot them down.” This aggravation led to large-scale violence between Black soldiers and the local law enforcement who targeted them. The Chief of Police and his men began moving through town, systematically disarming Black soldiers by force. Hundreds of shots were fired at the cavalrymen by the police officers and civilian white vigilantes.

Not all of the Black servicemen had been disarmed and those men returned fire. Some of them were wounded, but no one was killed, and the 10th Cavalry Regiment joined the Fourth of July parade the following day. Read more.

1940: Black World’s Fair Held in Chicago

To celebrate the 75th anniversary of the ending of slavery in the United States, the Black World’s Fair, also known as the American Negro Exposition, was held at the Chicago Coliseum from July 4 through September 2, 1940.

As the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture notes, “Featuring the contributions of African Americans to American life since 1865, the Exposition was considered the first Negro World’s Fair and the first time that African Americans had the opportunity to present themselves and their stories to the world.”

There were 120 exhibits on display, comprised of over 300 paintings and drawings, 33 dioramas, and much more. Admission was a quarter. Numerous local and national organizations and businesses participated. While the event itself only lasted for a few months, it took years to organize and plan.

Learn more in the related This Day in History post.

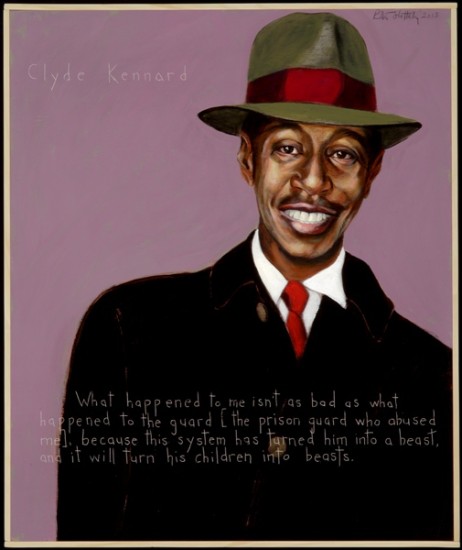

1963: Unsung Hero Clyde Kennard Died

On July 4, 1963, Clyde Kennard, an unsung hero of civil rights, died at the age of 36 from cancer. When Kennard returned from fighting in the Korean War, he put his life on the line in the 1950s by attempting to enroll at Mississippi Southern College (now USM-Hattiesburg) and seeking to become the first African American to attend. Kennard wrote poignant letters about the need for desegregation and his right to attend Mississippi Southern College.

Instead of being admitted, the state of Mississippi framed him on criminal charges for a petty crime and sentenced him to seven years of hard labor at Parchman Penitentiary where he was beaten and serious health problems went untreated.

Read more about Kennard’s brave story and his moving letters on the Zinn Education Project website.

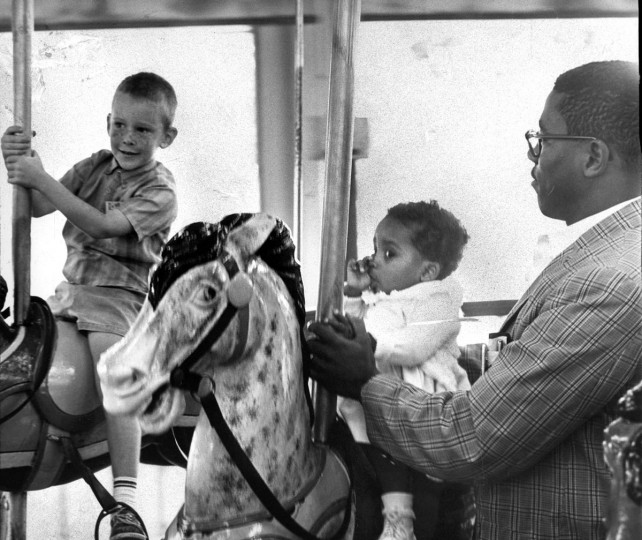

1963: Hundreds Non-Violently Protest Gwynn Oak Amusement Park’s Segregation Policy

Charles Langley holds his daughter, Sharon, the first African American to ride at the Gwynn Oak Park, August 28, 1963. Image: Baltimore Sun.

On July 4, 1963, civil rights demonstrators amassed on Gwynn Oak Amusement Park in Baltimore, Maryland, to protest the park’s segregation policy. Hundreds of activists from Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and Baltimore met at Gwynn Oak to protest their refusal to admit African Americans. Nearly 300 people were arrested at the demonstration, including more than 20 clergy — Catholic, Jewish, and Protestant — “the first time that so large a group of important clergymen of all three major faiths had participated together in a direct concerted protest against discrimination,” the New York Times wrote.

When asked by a reporter why he had joined other clergy to be arrested, Baltimore’s Rabbi Morris Lieberman replied, “I think every American should celebrate the Fourth of July.”

Baltimore’s Reverend Marion C. Bascom, who was arrested that day, said, “So if I do not preach at my pulpit Sunday morning, it might be the most eloquent sermon I ever preached.”

Read more at Round and Round Together: Taking a Merry-Go-Round Ride Into the Civil Rights Movement.

1965: First Annual Reminder Demonstration for Gay and Lesbian Rights

Barbara Gittings (center) picketing. Source: New York Public Library

Only July 4, 1965, 40 gay and lesbian activists held the first Annual Reminder demonstration in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, symbolically held in front of Independence Hall, meant to draw attention to the civil rights still due to the LGBTQ+ community. Frank Kameny and Barbara Gittings were the principal organizers of this event, one of the many pre-cursors to the Stonewall Rebellion of 1969 that ignited the LGBTQ+ movement on a national level. Read more at LGBT50.org. Visit the Barbara Gittings and Kay Tobin Lahusen Gay History Papers and Photographs collection at the New York Public Library.

Explore resources on LGBTQ+ issues at the Zinn Education Project. Find additional photographs from the Barbara Gittings and Kay Tobin Lahusen Gay History Papers and Photographs collection at the New York Public Library.

1966: Minimum Wage March Began

On July 4, 1966, the Minimum Wage March began in Rio Grande City, Texas, by the Independent Workers’ Association, a predominantly Mexican American union of farmworkers, to gain $1.25 minimum wage and be recognized as the bargaining agent. After previous strikes in the fields, the farm workers decided to take their issues to the state capital and raise public awareness of their demands for a living wage. When negotiations with state politicians failed, farmworkers continued to protest through the 1967 farming season. In September 1967, Hurricane Beulah hit the farm region, devastating crops. The union then shifted its focus to providing services to farm families. Read more and see photos at the University of Texas-San Antonio Archives.

Use the teaching activity “What Rights Do We Have?” to teach some of the nuts and bolts of labor unions and to invite students to consider what rights they have at work.

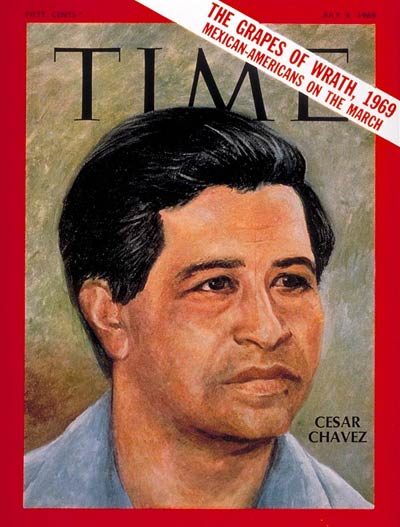

1969: Cesar Chavez on Cover of Time Magazine

On July 4, 1969, leader of the United Farmworkers Cesar Chavez appeared on the cover of Time magazine. At the height of the California Grape Boycott campaign, a union of Filipino and Mexican American farm workers, Chavez was cast as the symbol for Mexican American civil rights. Dr. Carlos Munoz Jr., Professor Emeritus of UC Berkeley’s Department of Ethnic Studies, recalls:

I remember feeling proud when his portrait appeared on the front page of Time magazine. I was elated that our struggles for social justice, civil rights, and peace, were finally being discovered by the nation — and, remarkably, on the Fourth of July.

The United Farmworkers went on to win its campaign, when the first union contracts were signed, granting workers better pay, benefits, and protections. Read more at the Farmworker Movement Documentation Project.

Explore resources on the United Farm Workers at the Zinn Education Project.

1976: Marion Prisoners Stage Bicentennial Hunger Strike

On July 4, 1976 inmates at United States Penitentiary (USP) Marion (in Illinois) staged a hunger strike in protest of inhumane treatment by the prison administration. They planned the strike for two years in order that it may coincide with the bicentennial celebration of the publication of the Declaration of Independence.

The prisoners involved in the planning — Eddie Griffin, Horace Graydon, Thomas Flood, Ed Jones and others — became known as the “Marion Brothers.” Following the results of the Attica Prison Rebellion three years earlier, the Marion Brothers had recognized the need to establish a network of outside support groups and media alliances prior to the day of the strike in order to publicize their struggle.

2013: “Restore the Fourth” Protests Draw Attention to the National Security Agency’s Spying Program

Restore the Fourth rally in San Francisco, 2013. Source: Justin Benttinen, The Guardian.

On July 4, 2013, rallies around the country protested the National Security Agency’s spying program, as brought to light by whistleblower Edward Snowden earlier that year. Organizers cited the 4th Amendment — “the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated” — in the mass collection of data undertaken by the U.S. government.

Read more about the protests and ways to take action at the Free Press website.

No comments:

Post a Comment