The U$ Federal Minimum Wage is Too Damn Low and Has Been for Too Damn Long

IT'S $15 AN HR IN CANADA

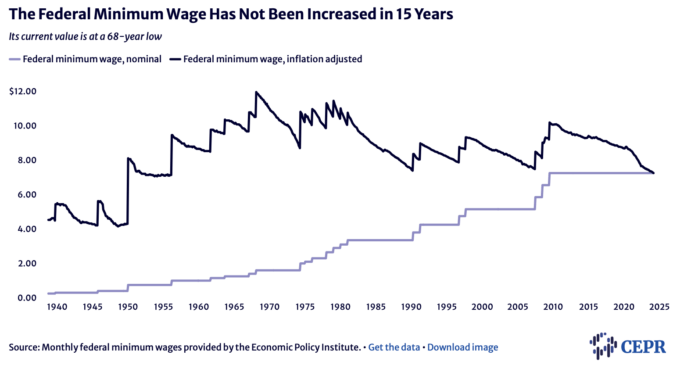

This July marks 15 years since the federal minimum wage was last increased. Given the federal wage floor is not indexed to inflation, nor any other measure such as productivity growth, it’s been stuck at $7.25 since July 24, 2009. Figure 1 shows that we are currently in the longest stretch of inaction on the federal minimum wage since its inception in 1938 — visible in the long $7.25 stretch in the nominal minimum wage running from 2009 to the present.

Figure 1

The federal wage floor has been increased just five times over the last three decades. Each jagged peak in the inflation-adjusted trend (dark line in Figure 1) represents a Congressionally legislated increase in the minimum wage followed immediately by a period of erosion due to inflation, signaling a decline in its buying power over time. Today the minimum wage is worth 29 percent less than when it was last increased in July 2009. What is worse, minimum wage workers in 2024 make nearly 40 percent less than their 1968 counterparts did when the minimum was at its most generous, worth about $12.00 in today’s dollars. But even $12.00 is a low bar given how much richer we are as a country now and how much more educated and productive today’s workers are than their 1960s counterparts. For instance, if the minimum had tracked the inflation-adjusted growth in average worker productivity since 1968, it would be over $26.00 today.1

By any reasonable standard, the federal wage floor is far too low and contributes to income, gender, and racial inequality. Higher minimum wages increase pay for our lowest-wage workers, especially for women and workers of color.2 Nowhere in the US can a full-time worker meet their basic needs on the federal minimum wage. Yet, 20 states follow the $7.25 federal policy. They are colored orange in Figure 2. The federal policy also applies to the states with no minimum wage laws (Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Tennessee), and the states that have minimums below the federal level (Georgia and Wyoming).

Figure 2

In the face of prolonged inaction at the federal level a kind of natural experiment has emerged across the country as more states have implemented higher wage floor standards. Today 30 states and the District of Columbia have minimums above the federal level — the average is $13.14, and they range from $8.75 in West Virginia (lightest blue) to $17.00 in DC (darkest blue) in Figure 2.3

Seven states plus the District of Columbia have minimums of at least $15 (California, Connecticut, District of Columbia, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Washington). Six other states have approved future increases to at least $15 in the next two years (Delaware, Illinois, and Rhode in 2025; and Florida, Hawaii, and Nebraska in 2026).

The geographic distribution of the $7.25 minimum wage states matters–especially as they are concentrated in the Southern Region. For example, while Black workers represent 11.5 percent of the workforce, 45.7 percent live in states that follow the $7.25 federal policy; comparatively 36.0 percent of the non-Black workforce live in those states.

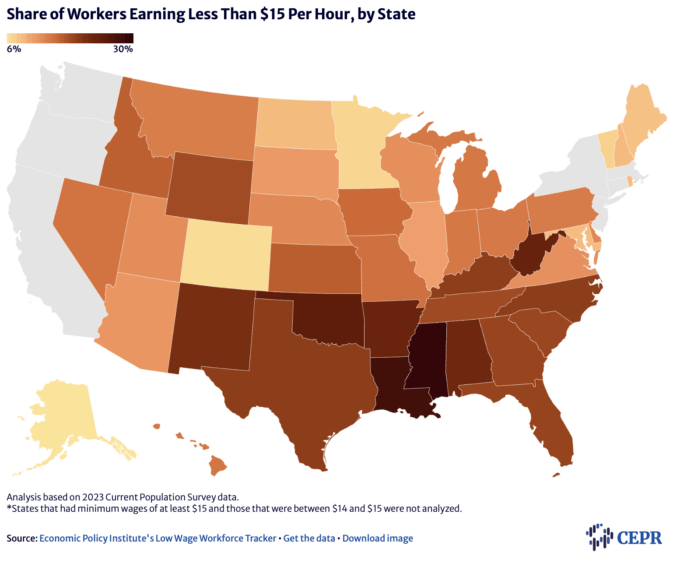

Figure 3 reports the share and number of all workers in each state who earn less than $15.00 per hour. These data are accessible via the Economic Policy Institute’s Low Wage Workforce Tracker. The LWW Tracker has a sliding wage scale where the amount paid to workers can be set from $10.00 to $25.00.4 The output in Figure 3 is from the State Data tab where the wage was set at $15.00 to analyze those earning less than that threshold.

Figure 3

States with the highest shares of low-wage workers are Mississippi (29.0 percent), Louisiana (27.3 percent), and Oklahoma (24.1 percent) — all of which follow the federal wage policy. In another four states, at least one in five of all workers earn wages below $15.00: West Virginia (23.1 percent) with an $8.75 wage floor, Arkansas (22.8 percent) with an $11.00 minimum, Alabama (22.0 percent) with a $7.25 floor, and New Mexico (20.9 percent) with a $12.00 minimum. The higher wage floors in Arkansas and New Mexico were implemented after fairly aggressive and recent increases, meaning that their reported shares represent workers earning $11.00 to $14.99, and $12.00 to $14.99, respectively.

The rest of the states are shaded from yellow to dark orange based on increasing shares of workers earning less than $15.00. While not perfectly correlated with state minimum wages, states with the highest shares of low-wage workers are concentrated in the South. Note, however, that the figure doesn’t show the share of workers below $15.00 in seven states and the District of Columbia (all denoted in grey) because the minimum wages in those areas were less than $1.00 below the $15.00 threshold.5

The federal standard is outdated and should be updated to lock in the wage gains that low-wage workers experienced from 2019–2023. There is nowhere in the US where a full-time worker can make ends meet on $7.25 an hour. While workers in many states are receiving higher pay, far too many have been left behind, which is why the federal wage floor matters.

The Fight for $15 and a Union that took hold in 2012 would be (adjusted for inflation) a fight for just over $20 today. The federal Raise the Wage Act (RTW Act), last introduced in 2023, did not pass. It would have increased the federal minimum in steps to $17 by 2028. The RTW Act would also have gradually raised and eventually eliminated the subminimum wage for tipped workers, which has been at $2.13 per hour since 1991.

Had the 2023 RTW Act been put into law the country would be on a path to higher wages. Once fully phased in, approximately 27.8 million workers, or about 19 percent of the workforce, would have received a pay increase amounting to $86 billion annually for our lowest wage earners.6

The argument that increasing the minimum wage from $7.25 to $17.00 is too much of a jump completely ignores the purposeful policy precedent of long periods of inaction on the federal wage floor that allows its value to erode significantly over time. This same argument also ignores the fact that $17.00 in 2023 is not worth $17.00 (adjusted for inflation) in 2028.

States are taking matters into their own hands, including states that historically never deviated from the federal wage floor (e.g., Arkansas ($11.00), Nebraska ($12.00), South Dakota ($11.20), Virginia ($12.00), and West Virginia ($8.75)). But there are too many states that will likely never act on their own to raise the minimum wage above the federal level.

You may have missed it in Figure 1, but in 1950 President Truman nearly doubled the federal minimum wage from an inflation-adjusted $4.30 to $8.06. There are many ways to get the country on a sustained path of living wages, but a lack of imagination seems to prevail. For instance, especially concerning small businesses, the tax code could be used to help with the transition. It is shameful that the US, the wealthiest country in the world, ranks #19 on minimum wages across the world.

Notes

1) CEPR economist Dean Baker provided the $26 update for 2024 to his previous work on minimum wages and productivity growth.

2) The Impact of the Raise the Wage Act of 2023, Economic Policy Institute, July 25, 2023.

3) There are nearly 60 local/city wide minimum wages across the country.

4) Additionally, the tracker has an interactive feature to report the output across all workers or by demographic groups (e.g., age, sex, race and ethnicity), or by education, firm size, occupation, industry, or union representation.

5) Not included were states that had minimums set to at least $15.00 (i.e., California, Connecticut, District of Columbia, Massachusetts, and Washington), and those where minimums were all above $14.00 and thus too close to the $15.00 threshold (i.e., New Jersey, New York, and Oregon).

6) The Impact of the Raise the Wage Act of 2023, Economic Policy Institute, July 25, 2023.

This analysis first appeared on CEPR.

No comments:

Post a Comment