Niall McCracken

BBC News NI

BBC

The large, windowless, concrete structure sits among houses in south Belfast

“This represents Northern Ireland’s place in the Cold War.”

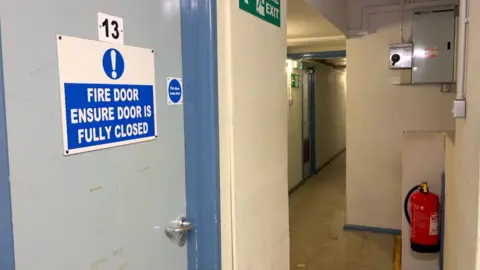

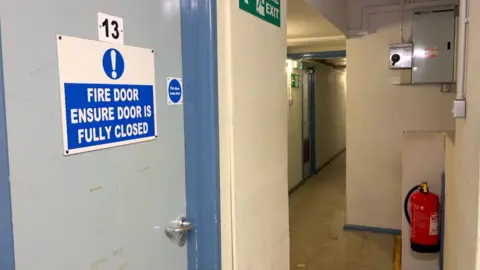

Archaeologist Rhonda Robinson can’t hide her enthusiasm as we walk down a dark, sterile stairway.

We’re going to the underground level of Northern Ireland’s forgotten nuclear bunker.

What makes the situation all the more surreal is that only moments ago we were above ground among the suburbs of south Belfast.

Rhonda Robinson is principal archaeologist for the Department for Communities

The large, windowless, concrete structure that sits among houses in Mount Eden Park, near Malone Road, was once known as The War Room.

I’ve been given rare access to the bunker ahead of it being repurposed as an archive for government documents.

Nuclear fallout

The building was first opened in 1952 as one of 13 Regional Government War Rooms throughout the UK.

It came in the aftermath of the detonation of the first nuclear weapon by America in 1945 and the development of atomic weapons by Russia in 1949.

It was constructed with the intention of being capable to withstand a nuclear attack, complete with blast doors and concrete walls that are 1.5m deep.

The building is covered in re-enforced concrete

The Cold War (1947 to 1991) refers to the period after World War Two when growing tensions between the Soviet Union and the US led to an arms race and the threat of renewed conflict.

With both sides owning huge nuclear arsenals, the world faced the real possibility of nuclear conflict.

In Northern Ireland, these events may have appeared distant, with the Troubles dominating local news during the latter part of this period.

But the Cold War did have an impact.

Dr James O'Neill is a heritage consultant with a specialism in Cold War-era buildings

Dr James O’Neill is a heritage consultant with a specialism in Cold War-era buildings.

He said: “The UK government realised they had to set up facilities for civil defence should the Cold War turn hot, so they built the war room here in Mount Eden.

“The setting might seem surprising, but it was meant to be out of the primary and secondary blast range of any atomic weapons aimed at Belfast city centre. Thankfully that didn’t happen.”

Should such an attack have occurred, the War Room would have coordinated things like search and recovery operations.

The former map room is located underground in the bunker

Located on the ground floor of the bunker is a huge empty space that used to be known as the map room.

A space where large windows used to be currently looks out at a blank wall.

This was the former location of a giant map of Northern Ireland where information on the nuclear fallout would have been displayed.

Having walls 1.5m thick with re-enforced concrete meant the nuclear radiation would have been reduced by a factor of 400.

The building was also complete with a ventilation system circulating fresh air and a pressure system that kept any nuclear dangers outside.

'Building became obsolete'

But Dr O’Neill said the usefulness of the bunker was short-lived.

“They finished the war room here by about 1953 but during that decade hydrogen bombs were developed and that changed everything - the building became obsolete," he said.

“The bunker was designed for nuclear fallout, but hydrogen weapons could crush this place like a beer tin.”

In 1958, the War Room moved to a location in Armagh.

A still from the BBC archive of what one of the rooms in the bunker looked like in the 1980s

In 1980, the Mount Eden Park bunker temporarily became a training facility for co-ordinating large-scale public emergencies.

Ten years later, another bunker designed to deal specifically with nuclear disasters was opened in Ballymena.

The Mount Eden Park bunker has gathered dust for decades, until now.

The listed building is going to be a new archive store for the Department for Communities’ (DfC) historical environment records.

Rhonda Robinson, principal archaeologist for DfC, said the building was "one of a kind".

“We want to make sure we look after these archives and find a sustainable reuse for rare buildings, so this is a great combination.

“The fact that this building is very cold, has thick walls and no windows, makes it perfect for archive storage."

The Department for Communities said it hopes to start construction on the renovation later this year.

The large, windowless, concrete structure sits among houses in south Belfast

“This represents Northern Ireland’s place in the Cold War.”

Archaeologist Rhonda Robinson can’t hide her enthusiasm as we walk down a dark, sterile stairway.

We’re going to the underground level of Northern Ireland’s forgotten nuclear bunker.

What makes the situation all the more surreal is that only moments ago we were above ground among the suburbs of south Belfast.

Rhonda Robinson is principal archaeologist for the Department for Communities

The large, windowless, concrete structure that sits among houses in Mount Eden Park, near Malone Road, was once known as The War Room.

I’ve been given rare access to the bunker ahead of it being repurposed as an archive for government documents.

Nuclear fallout

The building was first opened in 1952 as one of 13 Regional Government War Rooms throughout the UK.

It came in the aftermath of the detonation of the first nuclear weapon by America in 1945 and the development of atomic weapons by Russia in 1949.

It was constructed with the intention of being capable to withstand a nuclear attack, complete with blast doors and concrete walls that are 1.5m deep.

The building is covered in re-enforced concrete

The Cold War (1947 to 1991) refers to the period after World War Two when growing tensions between the Soviet Union and the US led to an arms race and the threat of renewed conflict.

With both sides owning huge nuclear arsenals, the world faced the real possibility of nuclear conflict.

In Northern Ireland, these events may have appeared distant, with the Troubles dominating local news during the latter part of this period.

But the Cold War did have an impact.

Dr James O'Neill is a heritage consultant with a specialism in Cold War-era buildings

Dr James O’Neill is a heritage consultant with a specialism in Cold War-era buildings.

He said: “The UK government realised they had to set up facilities for civil defence should the Cold War turn hot, so they built the war room here in Mount Eden.

“The setting might seem surprising, but it was meant to be out of the primary and secondary blast range of any atomic weapons aimed at Belfast city centre. Thankfully that didn’t happen.”

Should such an attack have occurred, the War Room would have coordinated things like search and recovery operations.

The former map room is located underground in the bunker

Located on the ground floor of the bunker is a huge empty space that used to be known as the map room.

A space where large windows used to be currently looks out at a blank wall.

This was the former location of a giant map of Northern Ireland where information on the nuclear fallout would have been displayed.

Having walls 1.5m thick with re-enforced concrete meant the nuclear radiation would have been reduced by a factor of 400.

The building was also complete with a ventilation system circulating fresh air and a pressure system that kept any nuclear dangers outside.

'Building became obsolete'

But Dr O’Neill said the usefulness of the bunker was short-lived.

“They finished the war room here by about 1953 but during that decade hydrogen bombs were developed and that changed everything - the building became obsolete," he said.

“The bunker was designed for nuclear fallout, but hydrogen weapons could crush this place like a beer tin.”

In 1958, the War Room moved to a location in Armagh.

A still from the BBC archive of what one of the rooms in the bunker looked like in the 1980s

In 1980, the Mount Eden Park bunker temporarily became a training facility for co-ordinating large-scale public emergencies.

Ten years later, another bunker designed to deal specifically with nuclear disasters was opened in Ballymena.

The Mount Eden Park bunker has gathered dust for decades, until now.

The listed building is going to be a new archive store for the Department for Communities’ (DfC) historical environment records.

Rhonda Robinson, principal archaeologist for DfC, said the building was "one of a kind".

“We want to make sure we look after these archives and find a sustainable reuse for rare buildings, so this is a great combination.

“The fact that this building is very cold, has thick walls and no windows, makes it perfect for archive storage."

The Department for Communities said it hopes to start construction on the renovation later this year.

No comments:

Post a Comment