‘Varda by Agnes’ allows pioneering film director to speak for herself

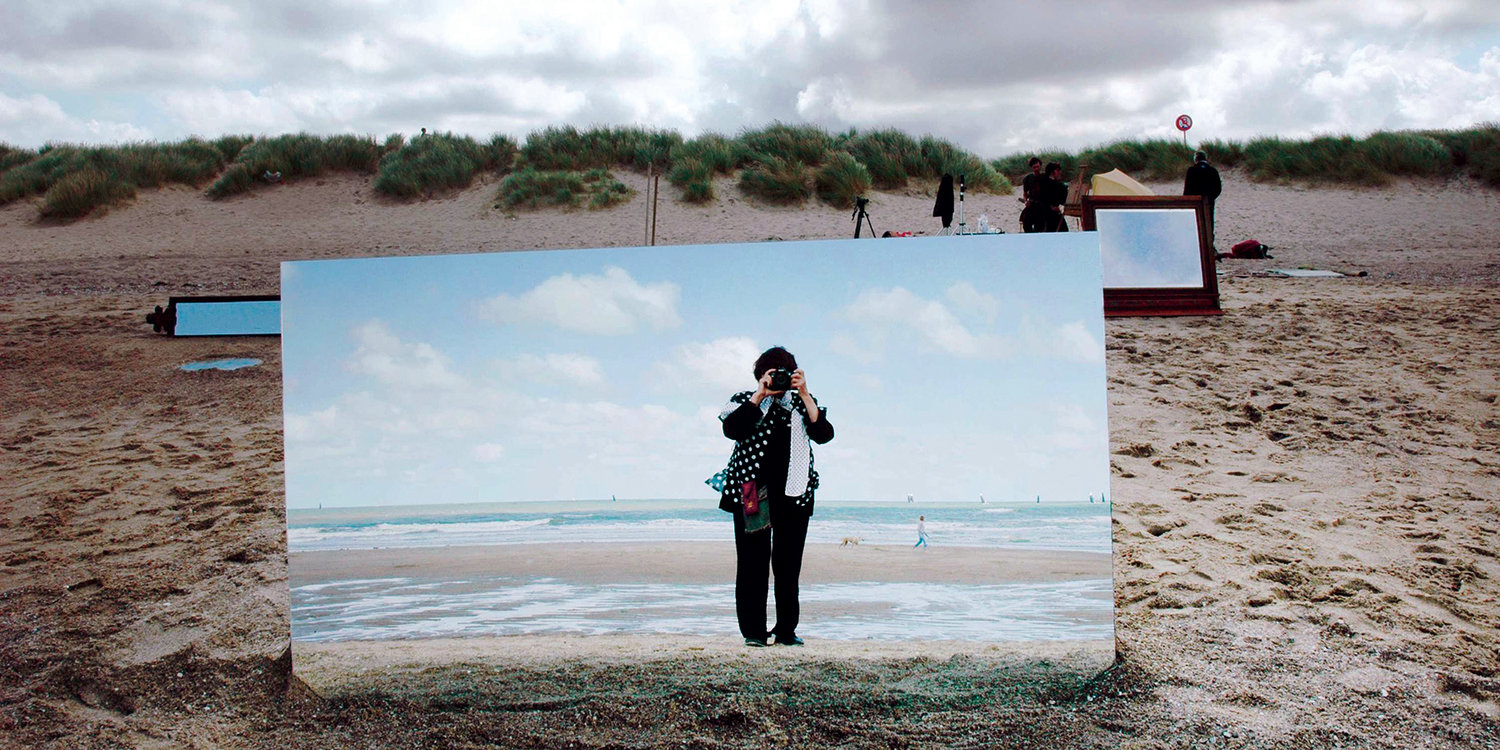

The artist captures a glimpse of herself in ‘Varda by Agnes,’ now playing at the Rose Theatre.

COURTESY PHOTO

Posted Wednesday, February 5, 2020

Kirk Boxleitner kboxleitner@ptleader.com

I last sampled Belgian-born French New Wave film director Agnes Varda’s work in my Dec. 6, 2017, review of the Academy Award-nominated “Faces Places” for The Leader, so it feels bittersweet to finally have the opportunity to do so again with “Varda by Agnes,” her final film, since she died last year at the age of 90.

Perhaps one of the most impressive aspects of a film career that spanned no fewer than six decades, and saw her shaping the development of the profoundly influential New Wave movement in film, is that Varda never stopped working, right up to the last, and even more, her most recent years were arguably among her most avant-garde, as she sought to redefine the entire nature of what a “film” could be.

This film basically consists of Varda regaling an audience of raptly attentive film aficionados with a series of endlessly fascinating anecdotes about her career, delivered with a dry and self-deprecating wit, and accompanied by corresponding clips, that I could have watched go on forever, even as they made my inner film reviewer cringe, because there’s no way I’ll be able to even briefly summarize those stories without feeling like I’ve left out something essential.

Varda started out as a still photographer of dramatic artists and theatrical types, including her future peers in filmmaking, and the dichotomy in her perspective was evident early on, because even as she admitted an affinity for staged shots, she also made it her mission to capture people on camera in their most unrehearsed moments.

We see this in 1967’s “Uncle Yanco,” a spur-of-the-moment short film that came about when Varda discovered a relative she didn’t even know she had in San Francisco, when we see her film multiple takes of her “first” meeting with her uncle Yanco Varda.

One of Varda’s early cinematographers recalls how the director sought to sneak in footage of village bakers and other ordinary people into her films, without making them aware they were on camera, and Sandrine Bonnaire, the lead actress of Varda’s 1985 “Vagabond,” recalls how she had to learn how to live as a nomadic backpacker for her role, at one point incurring blisters from repairing her own well-worn hiking shoes by hand.

Although Varda has directed celebrity actors such as Catherine Deneuve and Robert De Niro, her empathy for the dispossessed remains a constant throughout her films and later multimedia art exhibits, whether by highlighting feminist issues and shooting a documentary about the Black Panthers during the 1960s and ‘70s, or by giving voice to the homeless and the hungry in the 21st Century.

Varda’s 2000 documentary, “The Gleaners and I,” not only took advantage of more discreetly compact filmmaking technology to film urban and rural gleaners, without making them feel like they were under a spotlight, but it was also a forerunner of Varda’s multiscreen exhibits, such as rooms in which she combined her video with still photographs and even tangible examples of what she was shooting, whether it was a floor full of gleaners’ potatoes, or a coating of sand to simulate the beach whose waves could be seen washing ashore on the screens.

With Varda’s 2004 “The Widows of Noirmoutier,” she strove to ensure every viewer would have an entirely unique experience, by allowing a set number of seats in the screening rooms, and having each widow speak on a separate screen — each screen with its own set of headphones — so that no two viewers heard the same widow share her recollections.

With this background, it’s little surprise that Varda’s experimentalism led her to collaborate with the pseudonymously named photographer “JR” on 2017’s “Faces Places,” which not only made the inhabitants of country towns and industrial workplaces into the subjects of the duo’s literally larger-than-life work, but also turned those people’s hometowns and workplaces into the canvases for that same oversized artwork.

In spite of the failing eyesight that afflicted her in her final years, Varda never turned a blind eye to the injustices of the world, but she retained her humanistic belief in people, and she stubbornly held onto her optimism for a better world to the point that, when she wanted to bask in the beach settings she so enjoyed, she had the beach brought to her, by flooding city streets with sand as part of one of her art exhibits, as seen in 2008’s “The Beaches of Agnes.”

No comments:

Post a Comment