UPDATED

How a massacre of Algerians in Paris was covered upBy Ahmed Rouaba

BBC News

The words "Here we drown Algerians" were scrolled on the embankment of the River Seine

"It was a miracle I was not thrown into the Seine," Algerian Hocine Hakem recalled about an infamous but little-known massacre in the French capital 60 years ago.

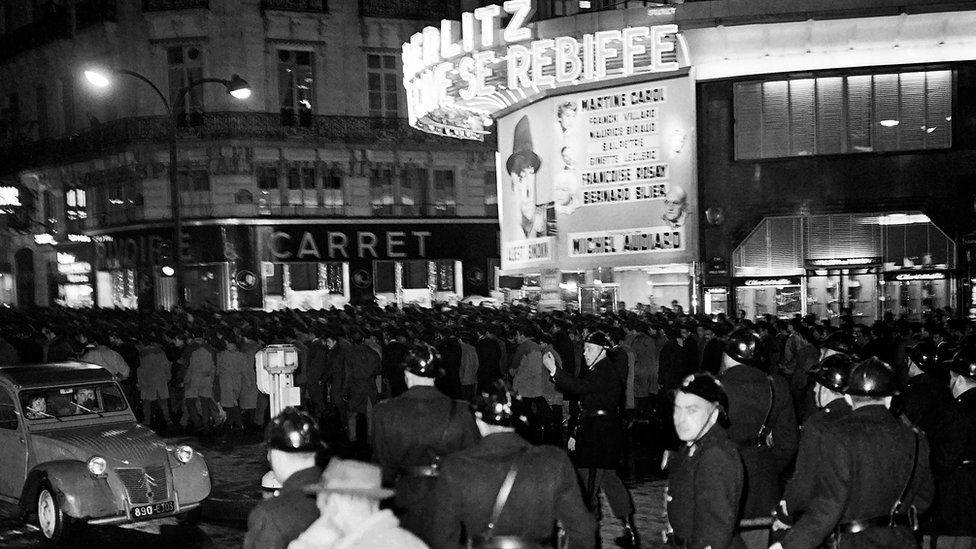

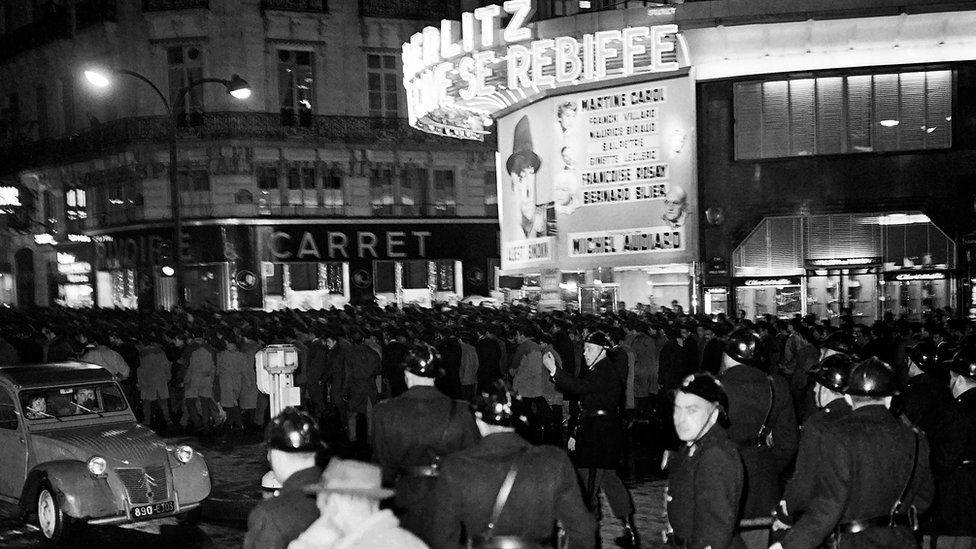

Around 30,000 Algerians had taken to the streets of Paris in a peaceful protest against a curfew, and calling for independence nearly seven years into the war against French rule in North Africa.

The police killed hundreds of protesters and dozens of others were thrown into the River Seine, making it one of the darkest pages of France's chequered colonial history.

Mr Hakem was 18 at the time and was telling his story to the L'Humanité newspaper decades after the event, which was little reported at the time. He was among about 14,000 Algerians arrested during the operation.

The government of the day censored the news, destroyed many of the archives and prevented journalists from investigating the story. Contemporary news bulletins reported three deaths, which included a French national. It was not covered in the international press.

Brigitte Laîné, who was a curator at the Parisian archives, said in 1999 that some official documents survived revealing the extent of the killings. "There were a lot of bodies. Some with the skulls crushed, others with shotguns wounds," she said.

One photo captured the chilling sentiments of the time, showing graffiti scrawled along a section of the Seine's embankment saying: "Here we drown Algerians."

This is the title of French historian Fabrice Riceputi's new book which details how one man - researcher Jean-Luc Einaudi - tirelessly sought to gather eyewitness testimony, publishing his account 30 years after the police massacre.

It is now believed that between 200 and 300 Algerians were killed that day.

A total of 110 bodies washed up on the banks of the River Seine over the following days and weeks . Some were killed then dumped, while others were injured, thrown into the cold waters and left to drown.

The youngest victim was Fatima Beda. She was 15 and her body was found on 31 October in a canal near the Seine.

Anti-Arab racism

One of the earliest descriptions of the event was published in 1963 by African-American writer William Gardner Smith in his novel Stone Face - though it is a fictionalised account, which has never been translated into French.

It shows the stark anti-Arab racism of the day.

In a statement to mark the 60th anniversary of the massacre, President Macron said that crimes committed under the authority of the police chief were "inexcusable".

Yet both have fallen short of the expectations of those who have been calling for an apology and reparations - and neither acknowledged how many people died or the state's role.

French left-wing parties, who were in opposition at the time, have also come in for criticism for not condemning the massacre. They have been seen as complicit in the cover-up given that they filed a law suit against the police for opening fire on mainly French anti-war protesters, killing seven, a few months later, and yet remained silent about the massacre of Algerians.

Mr Riceputi says the racist nature of the operation cannot be ignored - every person who looked Algerian was targeted.

The campaign waged against Algerians in Paris was unofficially called the "ratonnade", meaning "rat-hunting".

The search for Algerians continued for days after 17 October, with the police making arrests on public transport and during house searches.

It was reported that Moroccans had to put up the sign "Moroccan" on their doors to avoid being harassed by repeated police raids.

Portuguese, Spanish and Italian immigrant workers with curly hair and dark complexions complained about systematic stop and searches as they were mistaken for Algerians by the police.

Researchers also say that it was not only the police and security forces who took part in the operation - firefighters and vigilantes were also involved.

Thousands were illegally deported to Algeria where they were detained in internment camps despite being French citizens.

Fearsome reputation

At the time President Charles de Gaulle was in advanced negotiations with Algeria's National Liberation Front (FLN) to end the war and agree to independence. The war ended five months later and independence followed in July 1962.

But in 1961, tensions were running high and on 5 October the Parisian authorities banned all Algerians from leaving their homes between 20:00 and 05:30.

The march was called in protest at the curfew. The organisers wanted to ensure it was peaceful and people were frisked before boarding trains and buses from the run-down suburbs to go into central Paris.

It has not yet been established what exact instructions were given to the security forces, but the Paris police chief at the time, Maurice Papon, had a notorious reputation.

He had served in Constantine in eastern Algeria where he supervised the repression and torture of Algerian political prisoners in 1956.

He was later convicted in French courts of overseeing the deportation of 1,600 Jews to Nazi concentration camps in Germany during World War Two when he was a senior security official under the Vichy government.

It was this prosecution - that took place between 1997 and 1998 - that lifted the lid on some of the classified archives relating to the 17 October massacre, and paved the way for extensive research into the extraordinary cover-up.

Preliminary official inquiries into the events were made - and a total of 60 claims were dismissed.

No-one was tried as the massacre was subject to the general amnesty granted for crimes committed during the Algerian War.

For Mr Riceputi the hope is that this 60th anniversary will help with efforts to establish the truth and determine the responsibility for one of the bloodiest police massacres in France's history.

More on Franco-Algerian relations:

VIEWPOINT: What Macron doesn't get about colonialism

"It was a miracle I was not thrown into the Seine," Algerian Hocine Hakem recalled about an infamous but little-known massacre in the French capital 60 years ago.

Around 30,000 Algerians had taken to the streets of Paris in a peaceful protest against a curfew, and calling for independence nearly seven years into the war against French rule in North Africa.

The police killed hundreds of protesters and dozens of others were thrown into the River Seine, making it one of the darkest pages of France's chequered colonial history.

Mr Hakem was 18 at the time and was telling his story to the L'Humanité newspaper decades after the event, which was little reported at the time. He was among about 14,000 Algerians arrested during the operation.

The government of the day censored the news, destroyed many of the archives and prevented journalists from investigating the story. Contemporary news bulletins reported three deaths, which included a French national. It was not covered in the international press.

Brigitte Laîné, who was a curator at the Parisian archives, said in 1999 that some official documents survived revealing the extent of the killings. "There were a lot of bodies. Some with the skulls crushed, others with shotguns wounds," she said.

One photo captured the chilling sentiments of the time, showing graffiti scrawled along a section of the Seine's embankment saying: "Here we drown Algerians."

This is the title of French historian Fabrice Riceputi's new book which details how one man - researcher Jean-Luc Einaudi - tirelessly sought to gather eyewitness testimony, publishing his account 30 years after the police massacre.

It is now believed that between 200 and 300 Algerians were killed that day.

A total of 110 bodies washed up on the banks of the River Seine over the following days and weeks . Some were killed then dumped, while others were injured, thrown into the cold waters and left to drown.

The youngest victim was Fatima Beda. She was 15 and her body was found on 31 October in a canal near the Seine.

Anti-Arab racism

One of the earliest descriptions of the event was published in 1963 by African-American writer William Gardner Smith in his novel Stone Face - though it is a fictionalised account, which has never been translated into French.

It shows the stark anti-Arab racism of the day.

About 30,000 Algerians came into Paris to protest about the curfew which they said was racist

Mr Riceputi believes the French state is still refusing to face up to this racist heritage.

As the 60th anniversary of the killing approached, the often testy relations between France and Algeria - which had been undergoing a slow rapprochement - have once more hit the buffers.

The spat began last month when France slashed the number of visas granted to Algerians, accusing its former colony of failing to take back those denied visas.

But it was an audience President Emmanuel Macron held with young descendants of those who had fought in the Algerian War that has prompted the most anger.

He questioned whether the Algerian nation would exist if it hadn't been for French colonisers.

It may have been meant in the spirit of debate but it has provoked a backlash from Algerians who see it as symptomatic of France's insensitivity and the cover-up of colonial crimes.

No apology

When it comes to the Paris massacre, the state has done very little.

In 2012 François Hollande recognised that it had happened - the first time a French president had done so.

Mr Riceputi believes the French state is still refusing to face up to this racist heritage.

As the 60th anniversary of the killing approached, the often testy relations between France and Algeria - which had been undergoing a slow rapprochement - have once more hit the buffers.

The spat began last month when France slashed the number of visas granted to Algerians, accusing its former colony of failing to take back those denied visas.

But it was an audience President Emmanuel Macron held with young descendants of those who had fought in the Algerian War that has prompted the most anger.

He questioned whether the Algerian nation would exist if it hadn't been for French colonisers.

It may have been meant in the spirit of debate but it has provoked a backlash from Algerians who see it as symptomatic of France's insensitivity and the cover-up of colonial crimes.

No apology

When it comes to the Paris massacre, the state has done very little.

In 2012 François Hollande recognised that it had happened - the first time a French president had done so.

A commemorative plate dedicated to the victims of the massacre was unveiled in 2019 on the banks of the Seine

In a statement to mark the 60th anniversary of the massacre, President Macron said that crimes committed under the authority of the police chief were "inexcusable".

Yet both have fallen short of the expectations of those who have been calling for an apology and reparations - and neither acknowledged how many people died or the state's role.

French left-wing parties, who were in opposition at the time, have also come in for criticism for not condemning the massacre. They have been seen as complicit in the cover-up given that they filed a law suit against the police for opening fire on mainly French anti-war protesters, killing seven, a few months later, and yet remained silent about the massacre of Algerians.

Mr Riceputi says the racist nature of the operation cannot be ignored - every person who looked Algerian was targeted.

Thousands of Algerians were rounded up and illegally deported

The campaign waged against Algerians in Paris was unofficially called the "ratonnade", meaning "rat-hunting".

The search for Algerians continued for days after 17 October, with the police making arrests on public transport and during house searches.

It was reported that Moroccans had to put up the sign "Moroccan" on their doors to avoid being harassed by repeated police raids.

Portuguese, Spanish and Italian immigrant workers with curly hair and dark complexions complained about systematic stop and searches as they were mistaken for Algerians by the police.

Researchers also say that it was not only the police and security forces who took part in the operation - firefighters and vigilantes were also involved.

Thousands were illegally deported to Algeria where they were detained in internment camps despite being French citizens.

Fearsome reputation

At the time President Charles de Gaulle was in advanced negotiations with Algeria's National Liberation Front (FLN) to end the war and agree to independence. The war ended five months later and independence followed in July 1962.

But in 1961, tensions were running high and on 5 October the Parisian authorities banned all Algerians from leaving their homes between 20:00 and 05:30.

It is only in the last 30 years that details about the massacre have come to light

The march was called in protest at the curfew. The organisers wanted to ensure it was peaceful and people were frisked before boarding trains and buses from the run-down suburbs to go into central Paris.

It has not yet been established what exact instructions were given to the security forces, but the Paris police chief at the time, Maurice Papon, had a notorious reputation.

He had served in Constantine in eastern Algeria where he supervised the repression and torture of Algerian political prisoners in 1956.

He was later convicted in French courts of overseeing the deportation of 1,600 Jews to Nazi concentration camps in Germany during World War Two when he was a senior security official under the Vichy government.

It was this prosecution - that took place between 1997 and 1998 - that lifted the lid on some of the classified archives relating to the 17 October massacre, and paved the way for extensive research into the extraordinary cover-up.

Preliminary official inquiries into the events were made - and a total of 60 claims were dismissed.

No-one was tried as the massacre was subject to the general amnesty granted for crimes committed during the Algerian War.

For Mr Riceputi the hope is that this 60th anniversary will help with efforts to establish the truth and determine the responsibility for one of the bloodiest police massacres in France's history.

More on Franco-Algerian relations:

VIEWPOINT: What Macron doesn't get about colonialism

Macron’s condemnation of 1961 massacre in Paris ‘not enough’, historians say

Issued on: 17/10/2021 -

Video by: Luke SHRAGO

Historians and activists in France have expressed disappointment that President Emmanuel Macron did not go further in his condemnation of the deadly crackdown in 1961 by Paris police on protest by Algerians, the scale of which was covered up for decades.

The president “recognised the facts: that the crimes committed that night under [Paris police prefect] Maurice Papon are inexcusable for the Republic," said a statement from the Elysée Palace.

“It’s not enough", lamented Rahim Rezigat, 81, former member of the France federation of the National Liberation Front (FLN).

Macron “is playing with words, for the sake of his electorate, which includes those who are nostalgic for French Algeria", said Rezigat, who attended an event organised in Paris on Saturday by the anti-racism NGO SOS Racisme, bringing together activists and youths from the Ile-de-France region to commemorate that deadly night.

On October 17, 1961, some 30,000 Algerians demonstrated peacefully at the call of the FLN resistance movement in response to a strict 8:30pm curfew imposed on Algerians in Paris and its suburbs.

Ten thousand police and gendarmes were deployed ahead of the demonstration. The repression was bloody, with several demonstrators shot dead, some of whose bodies were thrown into the River Seine. Historians estimate that at least several dozen and up to 200 people were killed, but the official toll is three dead and 11,000 wounded.

>> Webdoc - October 17, 1961: A massacre of Algerians in the heart of Paris

‘A state crime’

Critics of Macron’s declaration Saturday say it did not go far enough and that pinning the blame solely on Papon is downplaying the state's in the massacre.

“Believing or expecting others to believe for one second that Maurice Papon could have acted of his own initiative throughout the month of October 1961, and especially on October 17, 1961, and that then interior minister Roger Frey and the entire government headed by Michel Debré were not responsible, is a fairy tale, and a bad one at that,” political scientist Oliver Le Cour Grandmaison, told FRANCE 24 on Sunday.

Knowing that power is exercised vertically in France's Fifth Republic, Le Cour Grandmaison said, “we consider that this was a state crime and therefore, we could have expected Emmanuel Macron’s declaration to reflect that. But there was no recognition, no law, no reparations. There wasn’t even a declaration. Macron didn’t speak,” he said, referring to the fact that the declaration was issued as a statement from the Elysée.

Gilles Manceron, a historian specialising in France’s colonial history agrees.

“This is a state crime, it is not a prefectural crime. It was a state crime that implicated a number of state officials and General De Gaulle, even though he did not direct the events himself and would also express his dissatisfaction with them, reportedly saying they were inadmissible – though secondary,” Manceron told FRANCE 24. “He didn’t direct the violence, and regretted it, but he covered it up with silence. Which contributed to the decades of silence that followed.”

Access to archives restricted

Human rights and anti-racism groups and Algerian associations in France staged a tribute march in Paris on Sunday afternoon. They called on authorities to further recognise the French state's responsibilities in the “tragedies and horrors” related to Algeria's independence war and to further open up archives from that period.

Earlier this year, Macron announced a decision to speed up the declassification of secret documents related to Algeria’s 1954-62 war of independence from France. The new procedure was introduced in August, Macron's office said.

The move was part of a series of steps taken by Macron to address France's brutal history with Algeria, which had been under French rule for 132 years until its independence in 1962.

But Le Cour Grandmaison, who heads an association for the commemoration of the October 17, 1961 events, said the archives were still very difficult to access.

“If you want to access the police archives, you have to ask the police prefecture, who is both judge and party to the events,” he told FRANCE 24. “Access to archives in France, compared to other democratic countries, is extremely restricted.”

Mancheron explained that “theoretically, French law dictates that archives should be communicable after a period of 50 years. But when the 50-year period was about to end concerning the archives of 1961, an interministerial directive was issued, saying a specific green light would be needed in order to open up certain archives. Which resulted in access being limited, even though it was permitted by law.

“Hence the mobilisation of historians and archivists and of a certain number of associations which last July led to the highest French court ruling that the interministerial directive of December 2011 was illegal, illegitimate, that it should not have been allowed, and it was canceled.”

>> Interview - 'We did our job, nothing more': The archivists who proved 1961 Paris massacre of Algerians

During the commemoration event Saturday night, SOS Racisme put on a pyrotechnics display at Pont Neuf, a bridge crossing the River Seine in the centre of Paris. The fireworks mimicked the bullets fired by the police 60 years ago as the Seine lit up and Algerian irises were thrown symbolically into the water.

On Sunday morning, Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo attended a tribute ceremony at the Saint-Michel bridge, in the capital's centre, and the Paris police prefect, Didier Lallement, laid a wreath of flowers at the site.

It was the first time a Paris police prefect paid tribute to the victims of October 17, 1961. Though he did not speak at the event, bells tolled and a minute of silence was observed.

Macron's political opponents from the right also criticised his declaration – this time for going too far.

“While #Algeria insults us every day, Emmanuel #Macron continues to belittle our country,” far-right presidential candidate Marine Le Pen tweeted on Saturday.

The sentiment was echoed by another far-right presidential hopeful, Nicolas Dupont Aignan, who tweeted, “Algeria spits on France and Emmanuel Macron does penance. The head of state must inspire pride, not shame in being French. Otherwise, how can we be surprised that immigrant populations do not wish to assimilate?”

And centre-right Les Républicains MP Eric Ciotti tweeted, “President Macron’s vicitimised anti-French propaganda is indecent. We’re still waiting for the president to commemorate the July 5, 1962 Oran massacre, when the FLN massacred several hundred pieds noirs and harkis [pro-French Muslims] loyal to France.”

In a message marking the 60th anniversary of the deadly crackdown, Algerian President Abdelmadjid Tebboune called Saturday for an approach free of "colonialist thought" on historical issues between his country and France.

"I reaffirm our strong concern for treating issues of history and memory without complacency or compromising principles, and with a sharp sense of responsibility", free from "the dominance of arrogant colonialist thought", he said.

The message came shortly after Tebboune declared that Algeria would observe a minute's silence each October 17 in memory of the victims.

Relations between Paris and Algiers have been strained amid a diplomatic spat fuelled by a visa row and comments attributed to the Macron describing Algeria as ruled by a "political-military system" that had "totally rewritten" its history.

Algeria has recalled its ambassador from Paris and banned French military planes from its airspace.

Tebboune has demanded France's "total respect".

"We forget that it (Algeria) was once a French colony ... History should not be falsified," he said last week.

(FRANCE 24 with AFP and AP)

Issued on: 17/10/2021 -

French President Emmanuel Macron lays a wreath of flowers near the Pont de Bezons (Bezons Bridge), on October 16, 2021 in Colombes, near Paris.

© Rafael Yaghobzadeh, Pool/AFP

Video by: Luke SHRAGO

Historians and activists in France have expressed disappointment that President Emmanuel Macron did not go further in his condemnation of the deadly crackdown in 1961 by Paris police on protest by Algerians, the scale of which was covered up for decades.

The president “recognised the facts: that the crimes committed that night under [Paris police prefect] Maurice Papon are inexcusable for the Republic," said a statement from the Elysée Palace.

“It’s not enough", lamented Rahim Rezigat, 81, former member of the France federation of the National Liberation Front (FLN).

Macron “is playing with words, for the sake of his electorate, which includes those who are nostalgic for French Algeria", said Rezigat, who attended an event organised in Paris on Saturday by the anti-racism NGO SOS Racisme, bringing together activists and youths from the Ile-de-France region to commemorate that deadly night.

On October 17, 1961, some 30,000 Algerians demonstrated peacefully at the call of the FLN resistance movement in response to a strict 8:30pm curfew imposed on Algerians in Paris and its suburbs.

Ten thousand police and gendarmes were deployed ahead of the demonstration. The repression was bloody, with several demonstrators shot dead, some of whose bodies were thrown into the River Seine. Historians estimate that at least several dozen and up to 200 people were killed, but the official toll is three dead and 11,000 wounded.

>> Webdoc - October 17, 1961: A massacre of Algerians in the heart of Paris

‘A state crime’

Critics of Macron’s declaration Saturday say it did not go far enough and that pinning the blame solely on Papon is downplaying the state's in the massacre.

“Believing or expecting others to believe for one second that Maurice Papon could have acted of his own initiative throughout the month of October 1961, and especially on October 17, 1961, and that then interior minister Roger Frey and the entire government headed by Michel Debré were not responsible, is a fairy tale, and a bad one at that,” political scientist Oliver Le Cour Grandmaison, told FRANCE 24 on Sunday.

Knowing that power is exercised vertically in France's Fifth Republic, Le Cour Grandmaison said, “we consider that this was a state crime and therefore, we could have expected Emmanuel Macron’s declaration to reflect that. But there was no recognition, no law, no reparations. There wasn’t even a declaration. Macron didn’t speak,” he said, referring to the fact that the declaration was issued as a statement from the Elysée.

Gilles Manceron, a historian specialising in France’s colonial history agrees.

“This is a state crime, it is not a prefectural crime. It was a state crime that implicated a number of state officials and General De Gaulle, even though he did not direct the events himself and would also express his dissatisfaction with them, reportedly saying they were inadmissible – though secondary,” Manceron told FRANCE 24. “He didn’t direct the violence, and regretted it, but he covered it up with silence. Which contributed to the decades of silence that followed.”

Access to archives restricted

Human rights and anti-racism groups and Algerian associations in France staged a tribute march in Paris on Sunday afternoon. They called on authorities to further recognise the French state's responsibilities in the “tragedies and horrors” related to Algeria's independence war and to further open up archives from that period.

Earlier this year, Macron announced a decision to speed up the declassification of secret documents related to Algeria’s 1954-62 war of independence from France. The new procedure was introduced in August, Macron's office said.

The move was part of a series of steps taken by Macron to address France's brutal history with Algeria, which had been under French rule for 132 years until its independence in 1962.

But Le Cour Grandmaison, who heads an association for the commemoration of the October 17, 1961 events, said the archives were still very difficult to access.

“If you want to access the police archives, you have to ask the police prefecture, who is both judge and party to the events,” he told FRANCE 24. “Access to archives in France, compared to other democratic countries, is extremely restricted.”

Mancheron explained that “theoretically, French law dictates that archives should be communicable after a period of 50 years. But when the 50-year period was about to end concerning the archives of 1961, an interministerial directive was issued, saying a specific green light would be needed in order to open up certain archives. Which resulted in access being limited, even though it was permitted by law.

“Hence the mobilisation of historians and archivists and of a certain number of associations which last July led to the highest French court ruling that the interministerial directive of December 2011 was illegal, illegitimate, that it should not have been allowed, and it was canceled.”

>> Interview - 'We did our job, nothing more': The archivists who proved 1961 Paris massacre of Algerians

During the commemoration event Saturday night, SOS Racisme put on a pyrotechnics display at Pont Neuf, a bridge crossing the River Seine in the centre of Paris. The fireworks mimicked the bullets fired by the police 60 years ago as the Seine lit up and Algerian irises were thrown symbolically into the water.

On Sunday morning, Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo attended a tribute ceremony at the Saint-Michel bridge, in the capital's centre, and the Paris police prefect, Didier Lallement, laid a wreath of flowers at the site.

It was the first time a Paris police prefect paid tribute to the victims of October 17, 1961. Though he did not speak at the event, bells tolled and a minute of silence was observed.

Criticised on the right

Macron's political opponents from the right also criticised his declaration – this time for going too far.

“While #Algeria insults us every day, Emmanuel #Macron continues to belittle our country,” far-right presidential candidate Marine Le Pen tweeted on Saturday.

The sentiment was echoed by another far-right presidential hopeful, Nicolas Dupont Aignan, who tweeted, “Algeria spits on France and Emmanuel Macron does penance. The head of state must inspire pride, not shame in being French. Otherwise, how can we be surprised that immigrant populations do not wish to assimilate?”

And centre-right Les Républicains MP Eric Ciotti tweeted, “President Macron’s vicitimised anti-French propaganda is indecent. We’re still waiting for the president to commemorate the July 5, 1962 Oran massacre, when the FLN massacred several hundred pieds noirs and harkis [pro-French Muslims] loyal to France.”

In a message marking the 60th anniversary of the deadly crackdown, Algerian President Abdelmadjid Tebboune called Saturday for an approach free of "colonialist thought" on historical issues between his country and France.

"I reaffirm our strong concern for treating issues of history and memory without complacency or compromising principles, and with a sharp sense of responsibility", free from "the dominance of arrogant colonialist thought", he said.

The message came shortly after Tebboune declared that Algeria would observe a minute's silence each October 17 in memory of the victims.

Relations between Paris and Algiers have been strained amid a diplomatic spat fuelled by a visa row and comments attributed to the Macron describing Algeria as ruled by a "political-military system" that had "totally rewritten" its history.

Algeria has recalled its ambassador from Paris and banned French military planes from its airspace.

Tebboune has demanded France's "total respect".

"We forget that it (Algeria) was once a French colony ... History should not be falsified," he said last week.

(FRANCE 24 with AFP and AP)

Blood and beatings: 1961 Paris Algerian massacre recalled

Issued on: 17/10/2021 -

"Algerians were also thrown, some alive, into the Seine by the police, but we will never know the exact number of bodies taken by this river," Sahili recalled.

According to him, even before the events of October 17 a good number of Algerian activists "ended up in the waters of the Seine" during police raids.

He recalled participating in the rescue of a young activist thrown into the Seine, saying he was found "at the last minute" and would have died were it not for his youth and health.

Following the independence of Algeria in 1962, Sahili remained in France for another two years before returning to his home country, where he built a career with national airline Air Algérie.

For decades, French authorities covered up the events of 1961 but Macron was the first president to attend a memorial for those who died on the day that Sahili cannot forget.

© 2021 AFP

Issued on: 17/10/2021 -

Rabah Sahili, who lived through the events of October 17, 1961 when dozens of Algerians were massacred in the middle of Paris, is pictured during an interview in Algiers on October 16, 2021

Ryad KRAMDI AFP

Algiers (AFP)

Rabah Sahili had just turned 19 when he arrived in central Paris for a peaceful demonstration by Algerians 60 years ago.

What he witnessed, he told AFP in an interview, was police savagery in a crackdown which killed dozens and perhaps as many as 200, according to historians' estimates. The official death toll at the time was three.

President Emmanuel Macron on Saturday condemned as "inexcusable" the crimes committed on October 17, 1961.

"The police and gendarmes showed atrocious brutality. They were raging to inflict harm," Sahili said, his voice breaking.

More than 30,000 Algerians had gathered to protest in Paris a decision to impose a curfew solely on the country's French Algerian minority.

The rally was called in the final year of France's increasingly violent campaign to retain Algeria as a north African colony. This coincided with a bombing campaign targeting mainland France by pro-independence militants.

On Saturday, Algerian President Abdelmadjid Tebboune announced that a minute of silence would be held the following day -- and each October 17 to commemorate the "martyrs" of the 1961 events.

Some were shot dead. Others had their bodies thrown into the River Seine.

The pro-independence National Liberation Front (FLN) had called on Algerian migrants from the capital's working class western suburbs to rally at a landmark square in Paris.

Other demonstrations were planned elsewhere in the city, and 10,000 policemen and gendarmes were deployed.

Sahili was arrested as he stepped off a train that arrived in Paris from Hautmont in the north, where he and his parents had lived for years.

"We had to meet at the Place de l'Etoile to start our peaceful demonstration. We had a single task: to make sure none of the demonstrators had any blunt instruments," he said.

Algiers (AFP)

Rabah Sahili had just turned 19 when he arrived in central Paris for a peaceful demonstration by Algerians 60 years ago.

What he witnessed, he told AFP in an interview, was police savagery in a crackdown which killed dozens and perhaps as many as 200, according to historians' estimates. The official death toll at the time was three.

President Emmanuel Macron on Saturday condemned as "inexcusable" the crimes committed on October 17, 1961.

"The police and gendarmes showed atrocious brutality. They were raging to inflict harm," Sahili said, his voice breaking.

More than 30,000 Algerians had gathered to protest in Paris a decision to impose a curfew solely on the country's French Algerian minority.

The rally was called in the final year of France's increasingly violent campaign to retain Algeria as a north African colony. This coincided with a bombing campaign targeting mainland France by pro-independence militants.

On Saturday, Algerian President Abdelmadjid Tebboune announced that a minute of silence would be held the following day -- and each October 17 to commemorate the "martyrs" of the 1961 events.

Some were shot dead. Others had their bodies thrown into the River Seine.

The pro-independence National Liberation Front (FLN) had called on Algerian migrants from the capital's working class western suburbs to rally at a landmark square in Paris.

Other demonstrations were planned elsewhere in the city, and 10,000 policemen and gendarmes were deployed.

Sahili was arrested as he stepped off a train that arrived in Paris from Hautmont in the north, where he and his parents had lived for years.

"We had to meet at the Place de l'Etoile to start our peaceful demonstration. We had a single task: to make sure none of the demonstrators had any blunt instruments," he said.

Rabah Sahili said his cousin suffered a broken leg from police blows, while trying to protect him

Ryad KRAMDI AFP

- 'It was savage' -

"I was with a cousin when the police descended upon us. Because he was stronger, he tried to protect me, but he received an avalanche of blows using the butts of guns and batons that caused his leg to break," Sahili recalled.

He said that people were being detained based solely on whether they appeared to be Algerian.

"All the Algerians coming out of the metro were arrested... even some Italians, Spanish people and South Americans" were held, he continued.

He noted that police and gendarmes were acting on firm instructions to target French Algerians.

Sahili said they were all driven "using batons" to a nearby car park, while trying to avoid being struck on the head.

"They had such a ferocity... It was savage, no more, no less," said the former FLN member.

"At midnight, we were moved to the Palais des Sports, where we remained for three days, under the watch of the police and harkis (auxillary forces)," he recounted.

The 9,000 people who, according to Sahili, were held in the sports dome were offered no more than a bottle of water and a snack.

Then they were taken to a "sorting facility" in the suburbs.

- 'Freezing cold' -

"The camp was devoid of absolutely all services: no beds, no toilets. We slept on the floor in the freezing cold," Sahili said.

"I stayed there for a fortnight before I was allowed to return home."

"During the arrests, I saw about 20 people lying on the ground bleeding near the Place de l'Etoile. There were many police and they behaved like ferocious beasts," he said.

- 'It was savage' -

"I was with a cousin when the police descended upon us. Because he was stronger, he tried to protect me, but he received an avalanche of blows using the butts of guns and batons that caused his leg to break," Sahili recalled.

He said that people were being detained based solely on whether they appeared to be Algerian.

"All the Algerians coming out of the metro were arrested... even some Italians, Spanish people and South Americans" were held, he continued.

He noted that police and gendarmes were acting on firm instructions to target French Algerians.

Sahili said they were all driven "using batons" to a nearby car park, while trying to avoid being struck on the head.

"They had such a ferocity... It was savage, no more, no less," said the former FLN member.

"At midnight, we were moved to the Palais des Sports, where we remained for three days, under the watch of the police and harkis (auxillary forces)," he recounted.

The 9,000 people who, according to Sahili, were held in the sports dome were offered no more than a bottle of water and a snack.

Then they were taken to a "sorting facility" in the suburbs.

- 'Freezing cold' -

"The camp was devoid of absolutely all services: no beds, no toilets. We slept on the floor in the freezing cold," Sahili said.

"I stayed there for a fortnight before I was allowed to return home."

"During the arrests, I saw about 20 people lying on the ground bleeding near the Place de l'Etoile. There were many police and they behaved like ferocious beasts," he said.

Bodies were thrown into the River Seine, here illuminated in red after a ceremony to commemorate the brutal repression of October 17, 1961

JULIEN DE ROSA AFP

"Algerians were also thrown, some alive, into the Seine by the police, but we will never know the exact number of bodies taken by this river," Sahili recalled.

According to him, even before the events of October 17 a good number of Algerian activists "ended up in the waters of the Seine" during police raids.

He recalled participating in the rescue of a young activist thrown into the Seine, saying he was found "at the last minute" and would have died were it not for his youth and health.

Following the independence of Algeria in 1962, Sahili remained in France for another two years before returning to his home country, where he built a career with national airline Air Algérie.

For decades, French authorities covered up the events of 1961 but Macron was the first president to attend a memorial for those who died on the day that Sahili cannot forget.

© 2021 AFP

No comments:

Post a Comment