Extreme heat, or "heatflation," is raising food prices everywhere. Researchers say that in the Middle East and other hotter regions, it will be even worse and negative impacts will be greater.

Over the past year, tomato prices in Iraq and Morocco have tripled due to heat and extreme weather

In Iraq, most people eat tomatoes with a meal at least once a day, sometimes more. Which is why, when tomato prices go up, people really start complaining, says Kholoud Salman, an Iraqi journalist based in Baghdad.

"Tomato prices went from 750 Iraqi dinars [$0.56, €0.52] for a kilo to 2,000 or even 2,500 last summer," Salman told DW. "People start posting complaints about it on Facebook. Last year I read a post by a young guy, who said that tomatoes were so expensive, his mother was guarding their refrigerator!"

Prices for food like tomatoes regularly change at local markets depending on how the crop has been impacted by weather or drought, Salman notes.

Tomatoes are particularly impacted by heat waves because in Iraq, these are often grown and sold by smallholder farms, who don't have any way of processing or refrigerating the crop. So they need to sell the perishables straight away.

"Thanks to the years of war, Iraq hasn't modernized agricultural production and the marketing of its products," Iraqi economist Mohammad al-Fakhri told DW. "Much is still done in traditional ways and it wastes the time and efforts of the Iraqi farmer."

Iraq is not the only Middle Eastern country where climate change is impacting food prices in such an immediate way.

Last September, onion prices in Egypt tripled in price to 35 Egyptian pounds ($0.74, €0.68), compared to earlier in the year. Egyptian officials said onion traders had caused the problem and they temporarily stopped onion exports. But onion growers themselves said a heat wave had reduced the harvest and the price rise was primarily due to this, alongside increased costs of production.

In Morocco last year, tomato growers suffered similar problems when an unexpected frost arrived after an unseasonably early spring. Tomato crops had blossomed too soon and the cold killed off new fruits. So where a kilogram of tomatoes previously cost 5 Moroccan dirhams ($0.50, €0.46) at local markets, it more than doubled to 12 dirhams. The Moroccan government then placed a partial ban on tomato exports.

This year, after the export ban was relaxed, tomato prices went up again and one local grower told Morocco's Journal24 media outlet that local farmers were giving up tomatoes because of the increased costs involved and the water needed.

Today a kilo of tomatoes costs 18 dirhams, Al Tayeb Ais, an economic expert from Rabat, told DW. For locals, "this is huge," he explained. "Because of the rise in prices, low-income families were no longer able to get the fruits, vegetables and meat they needed."

What is 'heatflation'?

All of these price rises come under the category of "heatflation," a phenomenon the World Economic Forum defines as steeply "rising food prices caused by extreme heat."

"There is no question that heatflation exists," Ulrich Volz, an economics professor and director of the Center for Sustainable Finance at SOAS, University of London, told DW. "The empirical evidence is clear that climate change is having increasing impacts on agricultural output and food prices around the world."

"Heatflation is very much a reality in the region," a spokesperson for the United Nation's World Food Program in the Middle East added. "As the climate continues to change, vulnerabilities are likely to intensify, further compromising the ability of the poorest communities to meet their basic food and nutrition needs."

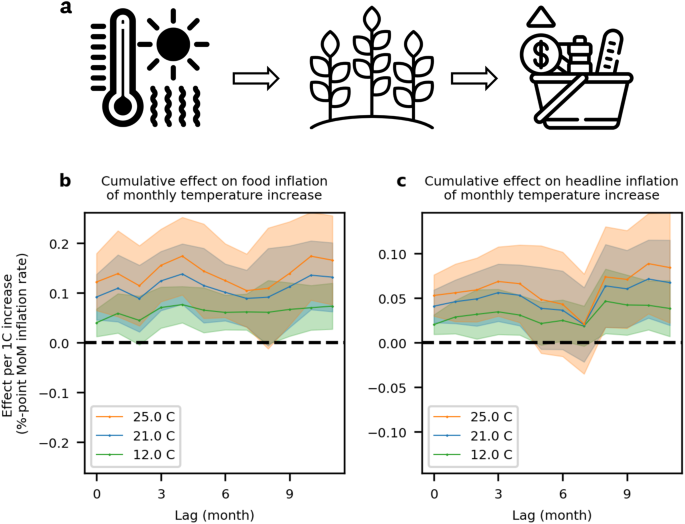

In a study published in March, researchers from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research and the European Central Bank looked at how heatflation might impact the cost of food in the future.

a A schematic outline of the mechanisms via which temperature shocks may impact inflation via agricultural productivity and food prices. The results of fixed-effects panel regressions from over 27,000 observations of monthly price indices and weather fluctuations worldwide over the period 1996-2021 demonstrate persistent impacts on food (b) and headline (c) prices from a one-off increase in monthly average temperature. Lines indicate the cumulative marginal effects of a one-off 1 C increase in monthly temperature on month-on-month inflation rates, evaluated at different baseline temperatures (colour) reflecting the non-linearity of the response by baseline temperatures which differ across both seasons and regions (see methods for a specific explanation of the estimation of these marginal effects from the regression models). Error bars show the 95% confidence intervals having clustered standard errors by country. Full regression results are shown in Tables S2 & S3. Icons are obtained from Flaticon (https://www.flaticon.com/) using work from Febrian Hidayat, Vectors Tank and Freepik.

The study investigated prices of food and other goods in 121 countries since 1996. Researchers concluded that by 2035, climate change could be pushing food prices up by between around 1% and 3% every year. By 2060, it could be increasing them by as much as 4.3% annually. And most of that increase would come from heat-related issues rather than excess rain or flooding, they wrote.

The researchers' estimates also showed heatflation was likely to have an even more dramatic affect in regions that were already hot, such as the Middle East, Africa and South America.

A few inflation percentage points may be a lot when it comes to European or North American food prices. For example, euro zone inflation was at 2.4% on average, during March and April. But in some Middle Eastern countries, overall — or headline — inflation is already in double and even triple digits. For example, in Egypt headline inflation is currently running at over 30%. Food price inflation is at over 40%.

No easy answers to tackle 'heatflation'

Other factors beyond heatflation cause the kinds of inflation rates seen in Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, Iran and Turkey, an April paper published by the International Monetary Fund explained. They include "budget deficits, high levels of public debt, currency devaluation, and dangerous levels of inflation" as well as conflict and war, and the dependency of some countries on food imports like wheat.

"Of course, there will always be other factors impacting on inflation, including macroeconomic developments and the exchange rate," London University's Volz told DW. "But food price inflation may indeed become more important."

For the time being, experts say it's important to acknowledge heatflation because rising food prices usually most affect the most vulnerable people in low-income households. Lack of nutrition can cause long-lasting developmental problems for children. Climbing food prices have caused all kinds of social unrest in the Middle East.

Unfortunately, just as with the topic of global climate change in general, there are no easy solutions to remedy heatflation.

"To prevent the worst from happening, Middle Eastern and North African countries, especially the oil producers, need to play their part in climate mitigation rather than obstructing it, as has been the case in the past," Volz argues. "Countries need to invest much more in adaptation and resilience in the agricultural sector, conduct climate risk analyses and develop suitable adaptation strategies."

How much heatflation affects the Middle East in the future, and therefore how high prices will rise, will depend on various factors but one of the most important will be how much countries invest in those kinds of solutions, he concluded.

Edited by: Rob Mudge

Cathrin Schaer Author for the Middle East desk.

No comments:

Post a Comment