Faulty system causes NASA to permanently change how Hubble Space Telescope points at its targets

The world's most famous space telescope will operate with only one gyroscope from now on.

BBC

Published: June 5, 2024

NASA is making a fundamental change to how the Hubble Space Telescope orientates itself to focus in on its targets.

The change affects Hubble's gyroscopes, which are the instruments that enable Hubble to swing up and down, left and right to focus in on a particular planet, nebula, galaxy or star cluster.

Gyros contain an internal wheel that spins at 19,200 revolutions per minute, enabling Hubble to change the direction in which it is pointing (known as 'slewing' in astronomy).

The space telescope would normally operate with 6 gyros, which were newly installed during the final Hubble servicing mission in 2009.

Out of the original six, just three gyros remain active, and the Hubble Space Telescope will now operate with only one

Why Hubble is moving down to one gyro

Over the past six months, one of Hubble's gyros has consistently given the NASA ground team on Earth faulty readings.

This has caused Hubble to enter 'safe mode' and led to a suspension of science observations.

The faulty gyro is experiencing something called 'saturation', NASA says, which means it's giving the Hubble science team readings that indicate the 'maximum slew rate' possible, regardless of how quickly the telescope is actually slewing.

And while Hubble engineers have been able to reset the gyro's electronics and return it to normal operations, this measure has proved only temporarily, with the gyro quickly returning to giving out false readings.

So, NASA has made the decision to operate Hubble with just one gyro for the rest of its operational life

How will one-gyro mode affect Hubble?

This one-gyro mode is not completely out of the blue: NASA had developed such a backup plan over 20 years ago as a means to extend the Hubble Space Telescope's lifespan.

NASA says "Hubble uses three gyros to maximise efficiency but can continue to make science observations with only one gyro," stating it's the "best operational mode to prolong Hubble’s life and allow it to successfully provide consistent science with fewer than three working gyros."

Naturally, however, there will be limitations.

In one-gyro mode, Hubble will need more time to slew and locate a target.

It won't have as much observing flexibility, meaning there will be be limitations as to where it can point at any given time.

And it will not be able to track moving objects closer than Mars.

What next?

Hubble engineers now need to work on reconfiguring the spacecraft and ground system, but also to consider whether this new operational mode will affect planned future observing projects.

Astronomers around the world apply for time using the Hubble Space Telescope to complete their observing projects, so the question is whether any of these projects might be affected by the telescope's new one-gyro mode.

Science operations are expected to resume by mid-June, says NASA.

"Once in one-gyro mode, NASA anticipates Hubble will continue making new cosmic discoveries alongside other observatories, such as the agency’s James Webb Space Telescope and future Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, for years to come."

Iain Tod

Science journalist

Iain Todd is BBC Sky at Night Magazine's Content Editor. He fell in love with the night sky when he caught his first glimpse of Orion, aged 10.

Boeing launches Nasa astronauts for the first time after years of delays

5 June 2024, 17:04

Wednesday’s launch was the third attempt with astronauts since early May.

Boeing launched astronauts for the first time on Wednesday, belatedly joining SpaceX as a second taxi service for Nasa.

Two Nasa test pilots blasted off aboard Boeing’s Starliner capsule for the International Space Station, the first to fly the new spacecraft.

The trip by Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams was expected to take 25 hours.

They will spend just over a week at the orbiting lab before climbing back into Starliner for a remote desert touchdown in the western US on June 14.

“Let’s get going,” Mr Wilmore called out minutes before liftoff.

Half an hour later, he and Ms Williams were safely in orbit and giving chase to the space station.

Back at Cape Canaveral, the relieved launch controllers stood and applauded. After all the trouble leading up to Wednesday’s launch, including two scrapped countdowns, everything seemed to go smoothly before and during liftoff.

Years late because of spacecraft flaws, Starliner’s crew debut comes as the company struggles with unrelated safety issues on its aeroplane side.

The astronauts stressed repeatedly before the launch that they had full confidence in Boeing’s ability to get it right with this test flight.

Crippled by bad software, Starliner’s initial test flight in 2019 without a crew had to be repeated before Nasa would let its astronauts strap in.

The 2022 attempt went much better, but parachute problems later cropped up and flammable tape had to be removed from the capsule.

Wednesday’s launch was the third attempt with astronauts since early May, coming after a pair of rocket-related problems, most recently last weekend.

A small helium leak in the spacecraft’s propulsion system also caused delays, but managers decided the leak was manageable and not a safety issue.

“I know it’s been a long road to get here,” Nasa’s commercial crew programme manager Steve Stich said before the weekend delay.

Boeing was hired alongside Elon Musk’s SpaceX a decade ago to ferry Nasa’s astronauts to and from the space station.

The space agency wanted two competing US companies for the job in the wake of the space shuttles’ retirement, paying 4.2 billion dollars (£3.3 billion) to Boeing and just over half that to SpaceX, which refashioned the capsule it was using to deliver station supplies.

SpaceX launched astronauts into orbit in 2020, becoming the first private business to achieve what only three countries – Russia, the US and China – had mastered.

It has taken nine crews to the space station for Nasa and three private groups for a Texas company that charters flights.

The lift-off from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station was the 100th of an Atlas V for rocket maker United Launch Alliance.

It was the first ride for astronauts on an Atlas rocket since John Glenn’s Mercury era more than 60 years ago; the rocket usually launches satellites and other spacecraft.

Despite the Atlas V’s perfect record, the human presence cranked up the tension for the scores of Nasa and Boeing employees gathered at Cape Canaveral and Mission Control in Houston.

Boeing’s Starliner and SpaceX’s Dragon are designed to be fully autonomous and reusable.

Mr Wilmore and Ms Williams occasionally will take manual control of Starliner on their way to the space station, to check out its systems.

If the mission goes well, Nasa will alternate between SpaceX and Boeing for taxi flights, beginning next year. The backup pilot for this test flight, Mike Fincke, will strap in for Starliner’s next trip.

“When you have a new spacecraft, you need to learn all about it and this has been a great exercise,” Mr Fincke told reporters late last week.

Cape Canaveral (AFP) – Boeing will be hoping the third time's a charm on Wednesday as they try once more to launch astronauts aboard a Starliner capsule bound for the International Space Station.

Issued on: 05/06/2024 -

Liftoff is targeted for 10:52 am (1452 GMT) from the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida, for a roughly one-week stay at the orbital laboratory.

The last attempt, on Saturday, was dramatically aborted with less than four minutes left of the countdown as the ground launch computer went into an automatic hold.

The problem was later traced to a faulty power supply source connected to the computer, with the malfunctioning unit since replaced.

And a buzzy valve on the United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket scuppered a previous attempt on May 6, a few hours before launch.

In both cases, astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams were strapped in and ready to go, only to be forced to return to strict quarantine in their quarters.

The Starliner program has already been beset by years of safety scares and delays, and a successful mission would offer Boeing a much-needed reprieve from the intense safety concerns surrounding its passenger jets.

NASA meanwhile is looking to certify Boeing as a second commercial operator to ferry crews to the ISS -- something Elon Musk's SpaceX has already been doing for the US space agency for four years.

Embarrassing setbacks

Both companies received multibillion-dollar contracts in 2014 to develop their crew capsules, following the end of the Space Shuttle program that left the US temporarily reliant on Russian rockets for rides.

Boeing, with its 100-year history, was heavily favored, but its program fell badly behind.

Setbacks ranged from a software bug that put the spaceship on a bad trajectory on its first uncrewed test, to the discovery that the cabin was filled with flammable electrical tape after the second.

While teams worked to replace the faulty rocket valve that postponed the previous launch attempt, a small helium leak located in one of Starliner's thrusters came to light.

Rather than replace the seal, which would require taking the spaceship apart in its factory, NASA and Boeing officials declared it safe enough to fly as is.

When they do fly, Wilmore and Williams will be charged with putting Starliner through the wringer, including taking manual control of the spacecraft on its way to the ISS.

During their stay on the research platform, the crew will carry out more tests, including simulating whether the ship can be used as a safe haven in the event of problems on the orbital outpost.

After undocking, Starliner will re-enter the atmosphere and carry out a parachute and airbag-assisted landing in the western United States.

© 2024 AFP

EXCITEMENT STILL GUARANTEED —

SpaceX is about to launch Starship again—the FAA will be more forgiving this time

The FAA has approved a license for SpaceX's fourth Starship launch, set for Thursday.

STEPHEN CLARK - 6/4/2024, ARS TECHNICA

Enlarge / The rocket for SpaceX's fourth full-scale Starship test flight awaits liftoff from Starbase, the company's private launch base in South Texas.

SpaceX60

The Federal Aviation Administration approved the commercial launch license for the fourth test flight of SpaceX's Starship rocket Tuesday, with liftoff from South Texas targeted for just after sunrise Thursday.

"The FAA has approved a license authorization for SpaceX Starship Flight 4," the agency said in a statement. "SpaceX met all safety and other licensing requirements for this test flight."

Shortly after the FAA announced the launch license, SpaceX confirmed plans to launch the fourth test flight of the world's largest rocket at 7:00 am CDT (12:00 UTC) Thursday. The launch window runs for two hours.

This flight follows three prior demonstration missions, each progressively more successful, of SpaceX's privately-developed mega-rocket. The last time Starship flew—on March 14—it completed an eight-and-a-half minute climb into space, but the ship was unable to maneuver itself as it coasted nearly 150 miles (250 km) above Earth. This controllability problem caused the rocket to break apart during reentry.

On Thursday's flight, SpaceX officials will expect the ascent portion of the test flight to be similarly successful as the launch in March. The objectives this time will be to demonstrate Starship's ability to survive the most extreme heating of reentry, when temperatures peak at 2,600° Fahrenheit (1,430° Celsius) as the vehicle plunges into the atmosphere at more than 20 times the speed of sound.

SpaceX officials also hope to see the Super Heavy booster guide itself toward a soft splashdown in the Gulf of Mexico just offshore from the company's launch site, known as Starbase, in Cameron County, Texas.

"The fourth flight test turns our focus from achieving orbit to demonstrating the ability to return and reuse Starship and Super Heavy," SpaceX wrote in an overview of the mission.

Last month, SpaceX completed a "wet dress rehearsal" at Starbase, where the launch team fully loaded the rocket with cryogenic methane and liquid oxygen propellants. Before the practice countdown, SpaceX test-fired the booster and ship at the launch site. More recently, technicians installed components of the rocket's self-destruct system, which would activate to blow up the rocket if it flies off course.

Then, on Tuesday, SpaceX lowered the Starship upper stage from the top of the Super Heavy booster, presumably to perform final touch-ups to ship's heat shield, comprised of 18,000 hexagonal ceramic tiles to protect its stainless-steel structure during reentry. Ground teams were expected to raise the ship, or upper stage, back on top of the booster some time Wednesday, returning the rocket to its full height of 397 feet (121 meters) ahead of Thursday morning's launch window.

The tick-tock of Starship's fourth flight

If all goes according to plan, SpaceX's launch team will start loading 10 million pounds of super-cold propellants into the rocket around 49 minutes before liftoff Thursday. The methane and liquid oxygen will first flow into the smaller tanks on the ship, then into the larger tanks on the booster.

The rocket should be fully loaded about three minutes prior to launch, and following a sequence of automated checks, the computer controlling the countdown will give the command to light the booster's 33 Raptor engines. Three seconds later, the rocket will begin its vertical climb off the launch mount, with its engines capable of producing more than 16 million pounds of thrust at full power.

Heading east from the Texas Gulf Coast, the rocket will exceed the speed of sound in about a minute, then begin shutting down its 33 main engines around 2 minutes and 41 seconds after liftoff. Then, just as the Super Heavy booster jettisons to begin a descent back to Earth, Starship's six Raptor engines will ignite to continue pushing the upper portion of the rocket into space. Starship's engines are expected to burn until T+plus 8 minutes, 23 seconds, accelerating the rocket to near orbital velocity with enough energy to fly an arcing trajectory halfway around the world to the Indian Ocean.Advertisement

All of this will be similar to the events of the last Starship launch in March. What differs in the flight plan this time involves the attempts to steer the booster and ship back to Earth. This is important to lay the groundwork for future flights, when SpaceX wants to bring the Super Heavy booster—the size of the fuselage of a Boeing 747 jumbo jet—to a landing back at its launch pad. Eventually, SpaceX also intends to recover reusable Starships back at Starbase or other spaceports.

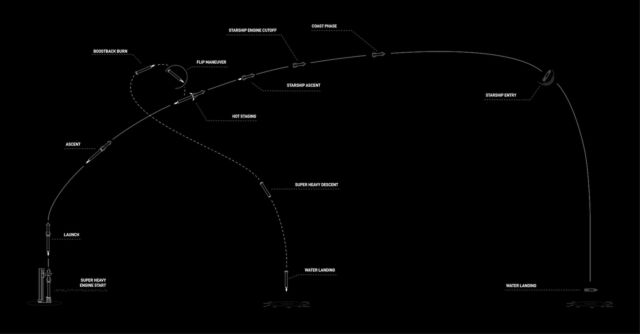

Enlarge / This infographic released by SpaceX shows the flight profile for SpaceX's fourth Starship launch.

SpaceX

Based on the results of the March test flight, SpaceX still has a lot to prove in these areas. On that flight, the engines on the Super Heavy booster could not complete all the burns required to guide the rocket toward the splashdown zone in the Gulf of Mexico. The booster lost control as it plummeted toward the ocean.

Engineers traced the failure to blockage in a filter where liquid oxygen flows into the Raptor engines. Notably, a similar problem occurred on the second Starship test flight last November. The Super Heavy booster awaiting launch Thursday has additional hardware to improve propellant filtration capabilities, according to SpaceX. The company also implemented "operational changes" on the booster for the upcoming test flight, including jettison of the Super Heavy's staging ring, which sits between the booster and ship during launch, to reduce the rocket's mass during descent.

SpaceX has a lot of experience bringing back its fleet of Falcon 9 boosters. The company now boasts a streak of more than 240 successful rocket landings in a row, so it's reasonable to expect SpaceX will overcome the challenge of recovering the larger Super Heavy booster.

The thorny issue of tiles

Starship, however, is a different animal. Despite having fewer engines, SpaceX's ambitions for the ship require it to be immensely more complex than the booster. Ultimately, these goals for Starship include satellite deployments, interplanetary transport, landings on the Moon and Mars, and refueling in orbit. But first, SpaceX must show that Starship can reliably travel between Earth's surface and low-Earth orbit.

On Flight 3 in March, the Starship upper stage lost the ability to control its orientation after turning off its main engines upon reaching space. SpaceX said engineers determined this was due to clogged valves used by reaction control thrusters on the upper stage, and the company said it is adding additional roll control thrusters on upcoming Starships.

The roll control problem prevented SpaceX from achieving two test objectives on the last Starship test flight. One was an attempt to reignite one of the ship's Raptor engines in space, a capability that SpaceX must routinely use on future Starship flights. The other was the controlled reentry of the 165-foot-long (50-meter) upper stage. Without fully functioning thrusters, the ship fell back into the atmosphere in the wrong attitude, and SpaceX lost contact with the vehicle due to excess heating.

This time, SpaceX will try to keep it simple. Of course, simple is a relative term when it comes to spaceflight and Starship. On Flight 4, there's no planned restart of a Raptor engine while the ship is in space. The lack of such a test on this flight means the next launch—Flight 5—will likely target a similar suborbital trajectory, rather than going all the way into orbit. Presumably, SpaceX, and perhaps federal regulators, would first like to see Starship prove it can execute a braking burn to return to Earth, rather than putting the vehicle into orbit and having it reenter the atmosphere unguided if the engine start failed.Advertisement

This vehicle also doesn't have a payload bay door like the last Starship opened and closed in space. Instead, the ship will drift through space until its flight path brings it back into the upper atmosphere around 47 minutes into the flight.

Enlarge / This rear-facing camera on Starship shows plasma building up around the vehicle during reentry over the Indian Ocean on the vehicle's most recent test flight in March.

SpaceX

That's when the ceramic tiles that make up Starship's heat shield will get to work. The tiles, each about the size of a dinner plate, are similar in function to those used on NASA's space shuttle, in that they insulate the ship's primary structure from the blistering heat of reentry.

Elon Musk, SpaceX's founder and CEO, wrote on X last week that gathering data on the tiles' performance in flight is vital.

"This is a matter of execution, rather than ideas," he wrote. "Unless we make the heat shield relatively heavy, as is the case with our Dragon capsule, where reliability is paramount, we will only discover the weak points by flying."

In order to make real Musk's lofty ambitions for a fully and rapidly reusable rocket, Starship's heat shield must be resilient and require little in the way of refurbishment between flights. SpaceX has a long way to go there.

"Right now, we are not resilient to loss of a single tile in most places, as the secondary containment material will probably not survive," Musk wrote. "This is a thorny issue indeed, given that vast resources have been applied to solve it, thus far to no avail."

If it survives the heat of reentry, Starship will descend into the lower atmosphere belly first and decelerate to subsonic speed under the control of aerodynamic flaps, similar to miniature wings. Finally, the ship will reignite a subset of its Raptor engines—probably two—and quickly flip from horizontal to vertical to settle into the waters of the Indian Ocean between Madagascar and Australia. If this happens, cue the champagne.

Regulatory waivers

The FAA also made some changes with the launch license for SpaceX's fourth Starship test flight that could speed up the process of issuing licenses for future launches.

With the first three Starship launches, the FAA license required SpaceX conduct a mishap investigation with federal oversight if the rocket failed to reach its destination intact. The outcome of the last test flight—Starship's breakup over the Indian Ocean—triggered such an investigation by SpaceX.

The FAA is charged with ensuring public safety during commercial space launches and reentries. In a Starship mishap investigation, the agency's role is to oversee the inquiry and accept the results of SpaceX's investigation before issuing a license for the next launch.

But this approach isn't congruent with SpaceX's roadmap for Starship development. SpaceX's iterative approach is rooted in test flights, where engineers learn what and what doesn't work, then try to quickly fix it and fly again. A crash, or two or three, is always possible, if not likely. The FAA is making an adjustment for this week's mission.

"As part of its request for license modification, SpaceX proposed three scenarios involving the Starship entry that would not require an investigation in the event of the loss of the vehicle," the FAA said in a statement.

Based on language in the code of federal regulations, the FAA has the option to approve these exceptions. The FAA accepted three possible outcomes for the upcoming Starship test flight that would not trigger what would likely be a months-long mishap investigation.

These exceptions include the failure of Starship's heat shield during reentry, if the ship's flap system is unable to provide sufficient control under high dynamic pressure, and the failure of the Raptor engine system during the landing burn. If one of these scenarios occurs, the FAA will not require a mishap investigation, provided there was no serious injury or fatality to anyone on the ground, no damage to unrelated property, and no debris outside designated hazard areas.

This change is quite significant for the FAA and SpaceX. It shows that federal regulators, suffering from staffing and funding shortages, are making moves to try and keep up with SpaceX's rapid, and often ever-changing, development of Starship.

"If a different anomaly occurs with the Starship vehicle, an investigation may be warranted, as well as if an anomaly occurs with the Super Heavy booster rocket," the FAA said.

STEPHEN CLARK is a space reporter at Ars Technica, covering private space companies and the world’s space agencies. Stephen writes about the nexus of technology, science, policy, and business on and off the planet.

No comments:

Post a Comment