It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way (K.Marx, Letter to F.Engels on the Indian Mutiny)

Saturday, October 18, 2014

The Subversion of Politics

European Autonomous Social Movements

and the Decolonization of Everyday Life

Copyright Georgy Katiaficas 1997,2006

European Autonomous Social Movements

and the Decolonization of Everyday Life

150 years later

Edited by Marcello Musto

With a special foreword

by Eric Hobsbawm

Philosophical, Economic and Political Dimensions

by Jacques Bidet

Translated by

David Fernbach

Foreword to the English Edition by Alex Callinicos

Michael Heinrich teaches economics in Berlin and is managing editor of PROKLA: Journal for Critical Social Science. He is the author of The Science of

Value: Marx’s Critique of Political Economy between Scientific Revolution and

Classical Tradition, and editor, with Werner Bonefeld, of Capital and Critique:

After the “New Reading" of Marx.

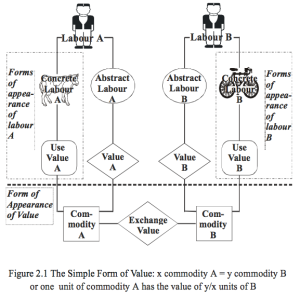

Marx’s Dialectics of Value and Knowledge

By Guglielmo Carchedi

Capital in general and many Capitals

Written in 1857/58 – during the first great world crisis (affecting not only the few industrial / industrializing countries but also the “rest of the world”)

Marx’ ambition: refutation of Say’s law, overcoming the fallacies of the “general glut debate”

Discovering the law / inner necessity of crisis in modern capitalism

Discovering / explaining the long term tendencies of capitalism (its historical laws of development)

Credit and Crisis

What is the final goal of Marx’ analysis?

To explain why and how capitalism is a self-destructive social system – undermining itself, destroying necessary preconditions which it can not reproduce / replace

To explain the limits of credit (which is a device to overcome many of the restrictions imposed upon capital)

To explain how and why the credit system in the end accelerates and aggravates the crises of capitalism

Why Credit?

Credit as a social device – rising from the exchange process

Credit presupposes capital – Capital presupposes credit

Credit links together money as money and money as capital

Credit provides the base for new forms of associated capital (the highest form, according to Marx)

Credit facilitates / accelerates the process of accumulation

Credit provides the most sophisticated form of social regulation of relations of production and exchange which are compatibel with capitalism (and already point beyond the capitalist mode of production, according to Marx)

Why Crisis?

The double meaning of crisis – both a symptom of the obsolescence of capitalism / and an element that slows down the decay of capitalism (enables fresh starts again and again – just because of the destruction of large portions of value and capital)

The dynamics of crisis – as a crucial phase in a longer process / as a decisive period of the trade cycle, industrial cycle

The different “forms of crisis” (among others: monetary crisis, credit crisis, financial crisis, industrial crisis …)

The long term tendency of crisis – to become world-wide, to become more and more severe

The range and scope of Marx’ theory of crisis

Crisis means the “explosion” of all contradictions of the capitalist mode of production

Crises are inevitable / necessary in capitalism as a temporary means to create new opportunities for capitalist development

A multifaceted phenomenon – the general crisis comprises several particular crises

Explanation has to be complex as well

Accordingly, there seem to be several Marxian “theories” of crisis (in fact, there are several causal chains that Marx follows and combines)

General conclusion – the meaning of the Grundrisse

The Grundrisse are not the “better or richer version” of Capital

They are just one stage in the long learning process of its author (learning how to build the critical theory) – althoug a very important one

The Grundrisse are a first big step towards Capital, no more, no less

Conclusion – Lessons that Marx drew

Writing “A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy” (1858, published in 1859)

Two versions (fragmentary “Urtext” and text as published in 1859

Lesson A: “The dialectical mode of exposition / presentation is only right, if one is aware of its limits” (Urtext)

Lesson B: Analysis of the commodity (form) and the exchange relation (process) is indispensable to develop the concept of money

Michael R. Krätke

Changing Worlds of Labour - Karl Marx and Beyond

Marx' theory or theories of crisis

Capitalism and its crises

Finance Capital - 100 years after Hilferding

AND MY WORK TIME, IS I GET PAID A LITTLE FOR MY WORK TIME

AND THE ABOLITION OF THE WAGE SYSTEM

The creation of a large quantity of disposable time apart from necessary labour time for society generally and each of its members (i.e. room for the development of the individuals’ full productive forces, hence those of society also), this creation of not-labour time appears in the stage of capital, as of all earlier ones, as not-labour time, free time, for a few. What capital adds is that it increases the surplus labour time of the mass by all the means of art and science, because its wealth consists directly in the appropriation of surplus labour time; since value directly its purpose, not use value. It is thus, despite itself, instrumental in creating the means of social disposable time, in order to reduce labour time for the whole society to a diminishing minimum, and thus to free everyone’s time for their own development. But its tendency always, on the one side, to create disposable time, on the other, to convert it into surplus labour. If it succeeds too well at the first, then it suffers from surplus production, and then necessary labour is interrupted, because no surplus labour can be realized by capital.The more this contradiction develops, the more does it become evident that the growth of the forces of production can no longer be bound up with the appropriation of alien labour, but that the mass of workers must themselves appropriate their own surplus labour. Once they have done so – and disposable time thereby ceases to have an antithetical existence – then, on one side, necessary labour time will be measured by the needs of the social individual, and, on the other, the development of the power of social production will grow so rapidly that, even though production is now calculated for the wealth of all, disposable time will grow for all.

For real wealth is the developed productive power of all individuals. The measure of wealth is then not any longer, in any way, labour time, but rather disposable time.Labour time as the measure of value posits wealth itself as founded on poverty, and disposable time as existing in and because of the antithesis to surplus labour time; or, the positing of an individual’s entire time as labour time, and his degradation therefore to mere worker, subsumption under labour. The most developed machinery thus forces the worker to work longer than the savage does, or than he himself did with the simplest, crudest tools.

FORDISM AND POST FORDISM IN THE GRUNDRISSE

Contradiction between the foundation of bourgeois production

(value as measure) and its development. Machines etc.

But to the degree that large industry develops, the creation of real wealth comes to depend less on labour time and on the amount of labour employed than on the power of the agencies set in motion during labour time, whose 'powerful effectiveness' is itself in turn out of all proportion to the direct labour time spent on their production, but depends rather on the general state of science and on the progress of technology, or the application of this science to production. (The development of this science, especially natural science, and all others with the latter, is itself in turn related to the development of material production.) Agriculture, e.g., becomes merely the application of the science of material metabolism, its regulation for the greatest advantage of the entire body of society. Real wealth manifests itself, rather -- and large industry reveals this -- in the monstrous disproportion between the labour time applied, and its product, as well as in the qualitative imbalance between labour, reduced to a pure abstraction, and the power of the production process it superintends. Labour no longer appears so much to be included within the production process; rather, the human being comes to relate more as watchman and regulator to the production process itself.

(What holds for machinery holds likewise for the combination of human activities and the development of human intercourse.) No longer does the worker insert a modified natural thing [Naturgegenstand] as middle link between the object [Objekt] and himself; rather, he inserts the process of nature, transformed into an industrial process, as a means between himself and inorganic nature, mastering it. He steps to the side of the production process instead of being its chief actor. In this transformation, it is neither the direct human labour he himself performs, nor the time during which he works, but rather the appropriation of his own general productive power, his understanding of nature and his mastery over it by virtue of his presence as a social body -- it is, in a word, the development of the social individual which appears as the great foundation-stone of production and of wealth.

The theft of alien labour time, on which the present wealth is based, appears a miserable foundation in face of this new one, created by large-scale industry itself. As soon as labour in the direct form has ceased to be the great well-spring of wealth, labour time ceases and must cease to be its measure, and hence exchange value [must cease to be the measure] of use value. The surplus labour of the mass has ceased to be the condition for the development of general wealth, just as the non-labour of the few, for the development of the general powers of the human head. With that, production based on exchange value breaks down, and the direct, material production process is stripped of the form of penury and antithesis. The free development of individualities, and hence not the reduction of necessary labour time so as to posit surplus labour, but rather the general reduction of the necessary labour of society to a minimum, which then corresponds to the artistic, scientific etc. development of the individuals in the time set free, and with the means created, for all of them.

Capital itself is the moving contradiction, [in] that it presses to reduce labour time to a minimum, while it posits labour time, on the other side, as sole measure and source of wealth. Hence it diminishes labour time in the necessary form so as to increase it in the superfluous form; hence posits the superfluous in growing measure as a condition -- question of life or death -- for the necessary. On the one side, then, it calls to life all the powers of science and of nature, as of social combination and of social intercourse, in order to make the creation of wealth independent (relatively) of the labour time employed on it. On the other side, it wants to use labour time as the measuring rod for the giant social forces thereby created, and to confine them within the limits required to maintain the already created value as value.

Forces of production and social relations -- two different sides of the development of the social individual -- appear to capital as mere means, and are merely means for it to produce on its limited foundation. In fact, however, they are the material conditions to blow this foundation sky-high. 'Truly wealthy a nation, when the working day is 6 rather than 12 hours. Wealth is not command over surplus labour time' (real wealth), 'but rather, disposable time outside that needed in direct production, for every individual and the whole society.' (The Source and Remedy etc. 1821, p. 6.)

Nature builds no machines, no locomotives, railways, electric telegraphs, self-acting mules etc. These are products of human industry; natural material transformed into organs of the human will over nature, or of human participation in nature. They are organs of the human brain, created by the human hand; the power of knowledge, objectified. The development of fixed capital indicates to what degree general social knowledge has become a direct force of production, and to what degree, hence, the conditions of the process of social life itself have come under the control of the general intellect and been transformed in accordance with it. To what degree the powers of social production have been produced, not only in the form of knowledge, but also as immediate organs of social practice, of the real life process.

POST MODERN ALCHEMY

GRUNDRISSE NOTEBOOK VI

February 1858, continued

Surplus value. Production time. Circulation time. Turnover time

Change of form and of matter in the circulation of capital.-- C-M-C. M-C-M.

A change of form [Formwechsel] and a change of matter [Stoffwechsel] take place simultaneously in the circulation of capital. We must begin here not with the presupposition of M, but with the production process. In production, as regards the material side, the instrument is used up and the raw material is worked up. The result is the product -- a newly created use value, different from its elemental presuppositions. As regards the material side, a product is created only in the production process. This is the first and essential material change. On the market, in the exchange for money, the product is expelled from the circulation of capital and falls prey to consumption, becomes object of consumption, whether for the final satisfaction of an individual need or as raw material for another capital. In the exchange of the commodity for money, the material and the formal changes coincide; for, in money, precisely the content itself is part of the economic form. The retransformation of money into commodity is here, however, at the same time present in the retransformation of capital into the material conditions of production. The reproduction of a specific use value takes place, just as well as of value as such. But, just as the material element here was posited, from the outset, at its entry into circulation, as a product, so the commodity in turn was posited as a condition of production at the end of it. To the extent that money figures here as medium of circulation, it does so indeed only as mediation of production, on one side with consumption, in the exchange where capital discharges value in the form of the product, and as mediation, on the other side, between production and production, where capital discharges itself in the form of money and draws the commodity in the form of the condition of production into its circulation. Regarded from the material side of capital, money appears merely as a medium of circulation; from the formal side, as the nominal measure of its realization, and, for a specific phase, as value-for-itself; capital is therefore C-M-M-C just as much as it is M-C- C-M, and this in such a way, specifically, that both forms of simple circulation here continue to be determinants, since M-M is money, which creates money, and C-C a commodity whose use value is both reproduced and increased. In regard to money circulation, which appears here as being absorbed into and determined by the circulation of capital, we want only to remark in passing -- for the matter can be thoroughly treated only after the many capitals have been examined in their action and reaction upon one another -- that money is obviously posited in different aspects here.

In machinery, the appropriation of living labour by capital achieves a direct reality in this respect as well: It is, firstly, the analysis and application of mechanical and chemical laws, arising directly out of science, which enables the machine to perform the same labour as that previously performed by the worker. However, the development of machinery along this path occurs only when large industry has already reached a higher stage, and all the sciences have been pressed into the service of capital; and when, secondly, the available machinery itself already provides great capabilities. Invention then becomes a business, and the application of science to direct production itself becomes a prospect which determines and solicits it. But this is not the road along which machinery, by and large, arose, and even less the road on which it progresses in detail. This road is, rather, dissection [Analyse] -- through the division of labour, which gradually transforms the workers' operations into more and more mechanical ones, so that at a certain point a mechanism can step into their places. (See under economy of power.) Thus, the specific mode of working here appears directly as becoming transferred from the worker to capital in the form of the machine, and his own labour capacity devalued thereby. Hence the workers' struggle against machinery. What was the living worker's activity becomes the activity of the machine. Thus the appropriation of labour by capital confronts the worker in a coarsely sensuous form; capital absorbs labour into itself -- 'as though its body were by love possessed'. [3]

3. 'als hätt es Lieb im Leibe', 'as it's lover in the body',Goethe, Faust, Pt I, Act 5, Auerbach's Cellar in Leipzig.

|

| METROPOLIS 1927 |

Thursday, October 16, 2014

Rashi Fein

Posted September 17th, 2014 in Uncategorized by Administrator No comments

Mass-Care is saddened by the news that our longtime friend and mentor Rashi Fein passed away on September 8, 2014 at the age of 88 from melanoma. Dr. Fein was a solid supporter of Mass-Care since its founding in 1995. He was a speaker at many events and his writing and his teaching kept generations of Single Payer advocates armed with facts and inspired by his steadfast belief that we can achieve a just health care system if we can generate the political will. As he wrote in his book “The Health Care Mess” in 2005, “Universal health insurance, access, and promotion of health are more than matters of health policy. In a fundamental sense they are matters of social policy and require a social revolution”. Mass-Care is a leader in the current social revolution over income disparity and inequality of opportunity. The goal of this movement is to galvanize a huge coalition of people from all segments of society to bring about progressive policy changes including a universal health care system.

Dr. Fein was a giant in his field of healthcare economics. Throughout his professional life he pursued his conviction that achieving a national healthcare system was the best way to provide affordable quality care for everyone. His core belief in equality and fairness was at the center of his goal for universal health care. He was instrumental in laying the groundwork for the passage of Medicare and Medicaid through his writings, personal contacts, and his work on various commissions under the administrations of President Truman, President Kennedy, and President Lyndon Johnson. It was a major disappointment for him that the passage of Medicare did not lead to further legislation calling for Medicare for all.

Dr. Fein received his doctorate in political economy in 1956 at John’s Hopkins and had a career teaching medical economics at several institutions including Chapel Hill, NC, and Harvard University. A former student of his who is now a Mass-Care activist had this to say about her student days under Dr. Fein’s tutelage. “Rashi, and we were encouraged to address him as Rashi, was always a most informative and compassionate teacher. No question was too simple for him. His passion for universal health care impressed many of us and helped to direct our careers. He was one in a million at the Harvard School of Public Health”. In addition to his teaching he worked on several presidential commissions on health economic policy, and he wrote many articles and published several books dealing with policies on healthcare including “Medical Care, Medical costs: The search for a Health Insurance Policy” 1986, “The Health Care Mess” co authored with Julius Richmond, MD in 2005, and “Learning Lessons: Medicine, Economics, and Public Policy” in 2010.

Dr. Fein and his wife Ruth were married for 65 years and were a team for social justice. We send Ruth and their family our deepest condolences.

For more details about Rashi Fein’s life please see the Boston Globe obituary from Sept. 11, 2014.

Medical costs are rising rapidly, and millions of people have no health care coverage. The nation urgently needs a universal insurance program

THE DOCTOR SHORTAGE. An Economic Diagnosis. RASHI FEIN. Washington, D. C., The Brookings Institution. 1967, 199 + xi pp. $2.50 (paperback).

Rashi Fein, Economist Who Urged Medicare, Dies at 88

By DOUGLAS MARTIN

Rashi Fein, an influential economist who strove to bring ethical and humanitarian perspectives to the nation’s health care system and helped lay the intellectual groundwork forMedicare in the 1960s, died on Monday in Boston. He was 88.

The cause was melanoma, his son Alan said.

When Dr. Fein began working on health issues as a young aide in the administration of Harry S. Truman, health care accounted for about 3 percent of the American economy. By the time he weighed in as a respected elder in the field during the debate over President Obama’s health care proposals, the expenditures had risen to 18 percent, an amount roughly equal to the economy of France.

As the money Americans spent on medical care increased, so did the role of economists specializing in health issues. Dr. Fein moved between government and academia, offering research and views on issues like meeting the demand for physicians. During the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson, he led a public-private panel to develop ideas for the Medicare legislation, which, along with Medicaid, was signed into law in 1965.Photo

Rashi Fein in 2000. He called for universal health coverage.CreditMichael Fein

Dr. Fein, a proud liberal, regretted that Medicare did not apply to everyone, just as he was disappointed that Mr. Obama’s Affordable Care Act did not consolidate insurance payments under the federal government. A federal single-payer system, he maintained, would be more cost effective and inclusive. The Obama plan, passed by Congress, relies on private insurance.

But Dr. Fein was nonetheless satisfied with incremental progress, Dr. Ezekiel J. Emanuel, chairman of the department of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania, said in an interview on Thursday. He quoted Dr. Fein, a former professor of his, as saying, “Getting everybody under the tent is better than standing on principle and not getting anything.”

Dr. Fein regarded both Medicare and the Affordable Care Act as important steps toward the overriding goal of helping “the people who have the least,” Dr. Emanuel said. In his 1986 book, “Medical Care, Medical Costs: The Search for a Health Insurance Policy,” Dr. Fein wrote, “Decent people — and we are decent people — are offended by unnecessary pain and suffering; that is, by pain and suffering for which there is a treatment and for which some (who are affluent) are treated.”

Mr. Fein was born in the Bronx on Feb. 6, 1926. His father, Isaac, was a history professor whose work took him to a chain of cities in the United States and Canada, including Winnipeg, Manitoba; and Bridgeport, Conn. His mother, the former Chaya Wertheim, was a schoolteacher.

Mr. Fein’s son Alan said his father and his father’s younger brother, Leonard — who went on to found organizations to combat hunger — had gotten their zeal for social justice from their parents.

“My preference for a universal insurance program derives from my image of a just society,” Dr. Fein wrote in his 1986 book. “It is an image based on a broadly defined concept of justice and liberty, nurtured by stories my parents told me, the books they encouraged me to read, and the values they expressed. To them, liberty meant more than political freedom; it also meant freedom from destitution — in Roosevelt’s phrase, ‘freedom from want.’ ”

After graduating from Central High School in Bridgeport, Dr. Fein was a Navy radar technician during World War II. He went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in economics and a doctorate in political economy from Johns Hopkins University.

In 1952, he took a teaching post at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, while working on a Truman administration commission charged with exploring the possibilities for national health insurance.

Six years later, he led a study by the federal Joint Commission on Mental Illness and Health, which estimated that mental illness cost the United States $3 billion a year ($24.7 billion in today’s dollars) in treatment costs and lost work years, a small fraction of the estimated costs today.

In 1961, Dr. Fein became a senior staff member on the Council of Economic Advisers under President John F. Kennedy. He studied education issues in addition to helping to write legislation for Medicare. He moved on to the Brookings Institution as a senior fellow in 1963 and remained with it while directing the Medicare panel for Johnson, Kennedy’s successor.

After leaving Brookings, Dr. Fein was a professor of economics at the Kennedy School of Government and the Medical School of Harvard University. He retired in 1999.

In addition to his son Alan, Dr. Fein is survived by his wife of 65 years, the former Ruth Judith Breslau; another son, Michael; a daughter, Karen Fein; and four grandchildren. Another daughter, Bena Fein, died in 1995. Dr. Fein’s brother, Leonard, died in August.

Dr. Fein spoke of the importance of language in describing health care, deriding the term “death panels” that some opponents used in the debate over the Affordable Care Act.

“A new language is infecting the culture of American medicine,” he wrote in The New England Journal of Medicine in 1982. “It is the language of the marketplace, of the tradesman, and of the cost accountant. It is a language that depersonalizes both patients and physicians and describes medical care as just another commodity. It is a language that is dangerous.”

By Bryan Marquard | GLOBE STAFF SEPTEMBER 11, 2014

MICHAEL FEIN

Dr. Rashi Fein was a tireless advocate of health care for all.

Rashi Fein was one of the policy architects of Medicare and he remained a lifelong proponent of health care for all. His advocacy never wavered, from his time working for the Truman, Kennedy, and Johnson administrations on through his long tenure as a Harvard economist.

“My first federal job was for a Harry Truman commission on national health insurance,” he wrote in the Globe in 2007. “For more than half a century I have believed and still believe that every American should have full access to needed medical care.”

His beliefs ran deeper than what could be accomplished in a political system that, in his view, seemed only willing to address the complexities of health care when access reached crisis levels, only to become gridlocked by the crisis itself.

“My preference for a universal insurance program derives from my image of a just society,” Dr. Fein wrote in “Medical Care, Medical Costs,” his 1986 book. “It is an image based on a broadly defined concept of justice and liberty, nurtured by stories my parents told me, the books they encouraged me to read, and the values they expressed. To them, liberty meant more than political freedom; it also meant freedom from destitution — in Roosevelt’s phrase, ‘freedom from want.’ ”

Dr. Fein, a professor emeritus of medical economics at Harvard Medical School who formerly served on the senior staff of President John F. Kennedy’s Council of Economic Advisers, died of melanoma Monday at Massachusetts General Hospital. He was 88 and lived in Boston.

In August 1964, Dr. Fein wrote in “Medical Care, Medical Costs,” he and the other members of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s task force on health convened to consider the nation’s health care needs.

“During that meeting the president emphasized the importance of a long-term vision,” Dr. Fein wrote. “He did not want us to recommend only what we felt was politically feasible within a year or even within a presidential term. Instead, we were to decide what health measures were desirable for the nation over the next two decades and to recommend legislation that would enable America to fulfill its promise.”

While the proposals Dr. Fein and his task force colleagues crafted helped lead to the creation of Medicare, Johnson made clear that as president, he would do the political heavy lifting. “He reminded us that we were amateurs and he was the professional,” Dr. Fein recalled.

Political strength may have turned Medicare into a reality, but through the years, Dr. Fein watched political paralysis thwart his hopes of turning Medicare into a steppingstone toward universal health care.

“The political process seems unwilling to address the problems that beset us until they become critical and complex,” he wrote in the 1980s. “It is as if simple questions need no answer and complex questions have no acceptable answer. Short of crisis, we need not act, yet in a crisis, we are often paralyzed.”

At Harvard, he was sought out by politicians, pundits, and reporters at every turn in the health care debate, from the failed Clinton plan in the 1990s through President Obama’s Affordable Care Act, which fell short of Dr. Fein’s vision of building on his achievement of helping to create Medicare.

“That was a passion that endured for his whole professional life,” said Dr. Fein’s son Alan of Cambridge, who added that “his greatest success was in that field and his greatest disappointment was in that field. We never had national health care.”

In a 1982 New England Journal of Medicine article, Dr. Fein lamented that the language of the marketplace had invaded health care and was poised to shift perceptions, as physicians became “providers” and their patients “consumers.”

“Medical care is not measured solely by the number of fractures set, hernias repaired, and appendixes removed, but also by the amount of comfort, concern, and compassion provided,” he wrote. “I want physicians — as well as more Americans — to speak the language that addresses the unfinished agenda of equity and decency in the distribution of health care.”

Allan Brandt, a history of medicine professor at Harvard Medical School who formerly was dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, said that “unlike some academics, there was absolutely no separation between his values and the programs and policies and social issues that he advocated for.”

Dr. Fein, he added, “had an incredible moral compass. In that sense he set a standard that colleagues like myself try to emulate.”

Born in New York City, Rashi Fein was the older of two intellectually accomplished brothers. Leonard Fein of Watertown, who died in August, was an activist and influential writer about Jews and Judaism.

Their father was a Jewish history professor whose work brought the family to several cities in the United States and Canada. Their mother taught in elementary schools.

Dr. Fein graduated from high school in Bridgeport, Conn., where he also studied briefly at a community college before serving in the Navy at the end of World War II.

After the war, he went to Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, from which he graduated with a bachelor’s in economics in 1948 and a doctorate in political economy in 1956. By then he was teaching at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

In 1949, he married Ruth Breslau, a graduate student at Johns Hopkins whom he met through Zionist youth organizations.

The family moved to the Washington, D.C., area when Dr. Fein joined the Kennedy administration, and remained when he became a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. In 1968, he took a faculty position at Harvard. For several years, beginning in the mid-1990s, he also chaired the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s National Advisory Committee for its Scholars in Health Policy Research program.

He wrote several books, beginning with “Economics of Mental Illness” in 1958 and concluding with “Learning Lessons: Medicine, Economics, and Public Policy,” in 2010.

“As a teacher he was a source of rock-solid advice in addition to sharing his scholarship,” said Joel Kavet, who had been a student of Dr. Fein’s and spent much of his career as a health administrator and health care planner. “A lot of us who had the benefit of his guidance look back now and among us the comment overall is, ‘He made a difference in my professional life.’ ”

A service was held Wednesday for Dr. Fein, who in addition to his wife, Ruth, and his son, Alan, leaves another son, Michael of Newton; a daughter, Karen of Sandwich; and four grandchildren.

“Someone said to me, ‘The thing about your dad is he was fair,’ ” Michael said. “I thought about that and, aside from his accomplishments and the things he worked on and had done in his life, he was concerned about fairness in the world. Fairness specifically in health care, but he was also very fair in his personal dealings with people.”

Dr. Fein, he said, skillfully mixed intellect with a common touch.

“He made information that was very important, but sometimes very complex, accessible to a variety of audiences in a variety of ways, and across generations as well,” Karen said. “He was good at telling a story in a way that lots of different people could hear it.”

Her father, she added, “was a humble man. We all have egos, but his was minimal at best. For anyone to spend most of his life so passionately trying to make a difference, I think that’s to be lauded.”

Posted September 17th, 2014 in Uncategorized by Administrator No comments

Mass-Care is saddened by the news that our longtime friend and mentor Rashi Fein passed away on September 8, 2014 at the age of 88 from melanoma. Dr. Fein was a solid supporter of Mass-Care since its founding in 1995. He was a speaker at many events and his writing and his teaching kept generations of Single Payer advocates armed with facts and inspired by his steadfast belief that we can achieve a just health care system if we can generate the political will. As he wrote in his book “The Health Care Mess” in 2005, “Universal health insurance, access, and promotion of health are more than matters of health policy. In a fundamental sense they are matters of social policy and require a social revolution”. Mass-Care is a leader in the current social revolution over income disparity and inequality of opportunity. The goal of this movement is to galvanize a huge coalition of people from all segments of society to bring about progressive policy changes including a universal health care system.

Dr. Fein was a giant in his field of healthcare economics. Throughout his professional life he pursued his conviction that achieving a national healthcare system was the best way to provide affordable quality care for everyone. His core belief in equality and fairness was at the center of his goal for universal health care. He was instrumental in laying the groundwork for the passage of Medicare and Medicaid through his writings, personal contacts, and his work on various commissions under the administrations of President Truman, President Kennedy, and President Lyndon Johnson. It was a major disappointment for him that the passage of Medicare did not lead to further legislation calling for Medicare for all.

Dr. Fein received his doctorate in political economy in 1956 at John’s Hopkins and had a career teaching medical economics at several institutions including Chapel Hill, NC, and Harvard University. A former student of his who is now a Mass-Care activist had this to say about her student days under Dr. Fein’s tutelage. “Rashi, and we were encouraged to address him as Rashi, was always a most informative and compassionate teacher. No question was too simple for him. His passion for universal health care impressed many of us and helped to direct our careers. He was one in a million at the Harvard School of Public Health”. In addition to his teaching he worked on several presidential commissions on health economic policy, and he wrote many articles and published several books dealing with policies on healthcare including “Medical Care, Medical costs: The search for a Health Insurance Policy” 1986, “The Health Care Mess” co authored with Julius Richmond, MD in 2005, and “Learning Lessons: Medicine, Economics, and Public Policy” in 2010.

Dr. Fein and his wife Ruth were married for 65 years and were a team for social justice. We send Ruth and their family our deepest condolences.

For more details about Rashi Fein’s life please see the Boston Globe obituary from Sept. 11, 2014.

Rashi Fein - Project MUSE - Johns Hopkins University

by R Fein - 1999 - Cited by 4 - Related articles

[Access article in PDF]. Changing Perceptions, Changing Reality. Rashi Fein. It should come as no surprise that Americans are deeply troubled about the ways ...Stories by Rashi Fein - Scientific American

The Doctor Shortage: An Economic Diagnosis by Rashi Fein

www.jstor.org/stable/3349299

The Doctor Shortage. An Economic Diagnosis. Rashi Fein ...

www.sciencemag.org › 29 December 1967by GJ Stigler - 1967 - Cited by 1 - Related articlesBook Reviews The Doctor Shortage. An Economic Diagnosis. Rashi Fein. Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C., 1967. 211 pp., illus. $6. Studies in Social...

By DOUGLAS MARTIN

Rashi Fein, an influential economist who strove to bring ethical and humanitarian perspectives to the nation’s health care system and helped lay the intellectual groundwork forMedicare in the 1960s, died on Monday in Boston. He was 88.

The cause was melanoma, his son Alan said.

When Dr. Fein began working on health issues as a young aide in the administration of Harry S. Truman, health care accounted for about 3 percent of the American economy. By the time he weighed in as a respected elder in the field during the debate over President Obama’s health care proposals, the expenditures had risen to 18 percent, an amount roughly equal to the economy of France.

As the money Americans spent on medical care increased, so did the role of economists specializing in health issues. Dr. Fein moved between government and academia, offering research and views on issues like meeting the demand for physicians. During the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson, he led a public-private panel to develop ideas for the Medicare legislation, which, along with Medicaid, was signed into law in 1965.Photo

Rashi Fein in 2000. He called for universal health coverage.CreditMichael Fein

Dr. Fein, a proud liberal, regretted that Medicare did not apply to everyone, just as he was disappointed that Mr. Obama’s Affordable Care Act did not consolidate insurance payments under the federal government. A federal single-payer system, he maintained, would be more cost effective and inclusive. The Obama plan, passed by Congress, relies on private insurance.

But Dr. Fein was nonetheless satisfied with incremental progress, Dr. Ezekiel J. Emanuel, chairman of the department of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania, said in an interview on Thursday. He quoted Dr. Fein, a former professor of his, as saying, “Getting everybody under the tent is better than standing on principle and not getting anything.”

Dr. Fein regarded both Medicare and the Affordable Care Act as important steps toward the overriding goal of helping “the people who have the least,” Dr. Emanuel said. In his 1986 book, “Medical Care, Medical Costs: The Search for a Health Insurance Policy,” Dr. Fein wrote, “Decent people — and we are decent people — are offended by unnecessary pain and suffering; that is, by pain and suffering for which there is a treatment and for which some (who are affluent) are treated.”

Mr. Fein was born in the Bronx on Feb. 6, 1926. His father, Isaac, was a history professor whose work took him to a chain of cities in the United States and Canada, including Winnipeg, Manitoba; and Bridgeport, Conn. His mother, the former Chaya Wertheim, was a schoolteacher.

Mr. Fein’s son Alan said his father and his father’s younger brother, Leonard — who went on to found organizations to combat hunger — had gotten their zeal for social justice from their parents.

“My preference for a universal insurance program derives from my image of a just society,” Dr. Fein wrote in his 1986 book. “It is an image based on a broadly defined concept of justice and liberty, nurtured by stories my parents told me, the books they encouraged me to read, and the values they expressed. To them, liberty meant more than political freedom; it also meant freedom from destitution — in Roosevelt’s phrase, ‘freedom from want.’ ”

After graduating from Central High School in Bridgeport, Dr. Fein was a Navy radar technician during World War II. He went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in economics and a doctorate in political economy from Johns Hopkins University.

In 1952, he took a teaching post at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, while working on a Truman administration commission charged with exploring the possibilities for national health insurance.

Six years later, he led a study by the federal Joint Commission on Mental Illness and Health, which estimated that mental illness cost the United States $3 billion a year ($24.7 billion in today’s dollars) in treatment costs and lost work years, a small fraction of the estimated costs today.

In 1961, Dr. Fein became a senior staff member on the Council of Economic Advisers under President John F. Kennedy. He studied education issues in addition to helping to write legislation for Medicare. He moved on to the Brookings Institution as a senior fellow in 1963 and remained with it while directing the Medicare panel for Johnson, Kennedy’s successor.

After leaving Brookings, Dr. Fein was a professor of economics at the Kennedy School of Government and the Medical School of Harvard University. He retired in 1999.

In addition to his son Alan, Dr. Fein is survived by his wife of 65 years, the former Ruth Judith Breslau; another son, Michael; a daughter, Karen Fein; and four grandchildren. Another daughter, Bena Fein, died in 1995. Dr. Fein’s brother, Leonard, died in August.

Dr. Fein spoke of the importance of language in describing health care, deriding the term “death panels” that some opponents used in the debate over the Affordable Care Act.

“A new language is infecting the culture of American medicine,” he wrote in The New England Journal of Medicine in 1982. “It is the language of the marketplace, of the tradesman, and of the cost accountant. It is a language that depersonalizes both patients and physicians and describes medical care as just another commodity. It is a language that is dangerous.”

Rashi Fein, 88; economist was an architect of Medicare

By Bryan Marquard | GLOBE STAFF SEPTEMBER 11, 2014

MICHAEL FEIN

Dr. Rashi Fein was a tireless advocate of health care for all.

Rashi Fein was one of the policy architects of Medicare and he remained a lifelong proponent of health care for all. His advocacy never wavered, from his time working for the Truman, Kennedy, and Johnson administrations on through his long tenure as a Harvard economist.

“My first federal job was for a Harry Truman commission on national health insurance,” he wrote in the Globe in 2007. “For more than half a century I have believed and still believe that every American should have full access to needed medical care.”

His beliefs ran deeper than what could be accomplished in a political system that, in his view, seemed only willing to address the complexities of health care when access reached crisis levels, only to become gridlocked by the crisis itself.

“My preference for a universal insurance program derives from my image of a just society,” Dr. Fein wrote in “Medical Care, Medical Costs,” his 1986 book. “It is an image based on a broadly defined concept of justice and liberty, nurtured by stories my parents told me, the books they encouraged me to read, and the values they expressed. To them, liberty meant more than political freedom; it also meant freedom from destitution — in Roosevelt’s phrase, ‘freedom from want.’ ”

Dr. Fein, a professor emeritus of medical economics at Harvard Medical School who formerly served on the senior staff of President John F. Kennedy’s Council of Economic Advisers, died of melanoma Monday at Massachusetts General Hospital. He was 88 and lived in Boston.

In August 1964, Dr. Fein wrote in “Medical Care, Medical Costs,” he and the other members of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s task force on health convened to consider the nation’s health care needs.

“During that meeting the president emphasized the importance of a long-term vision,” Dr. Fein wrote. “He did not want us to recommend only what we felt was politically feasible within a year or even within a presidential term. Instead, we were to decide what health measures were desirable for the nation over the next two decades and to recommend legislation that would enable America to fulfill its promise.”

While the proposals Dr. Fein and his task force colleagues crafted helped lead to the creation of Medicare, Johnson made clear that as president, he would do the political heavy lifting. “He reminded us that we were amateurs and he was the professional,” Dr. Fein recalled.

Political strength may have turned Medicare into a reality, but through the years, Dr. Fein watched political paralysis thwart his hopes of turning Medicare into a steppingstone toward universal health care.

“The political process seems unwilling to address the problems that beset us until they become critical and complex,” he wrote in the 1980s. “It is as if simple questions need no answer and complex questions have no acceptable answer. Short of crisis, we need not act, yet in a crisis, we are often paralyzed.”

At Harvard, he was sought out by politicians, pundits, and reporters at every turn in the health care debate, from the failed Clinton plan in the 1990s through President Obama’s Affordable Care Act, which fell short of Dr. Fein’s vision of building on his achievement of helping to create Medicare.

“That was a passion that endured for his whole professional life,” said Dr. Fein’s son Alan of Cambridge, who added that “his greatest success was in that field and his greatest disappointment was in that field. We never had national health care.”

In a 1982 New England Journal of Medicine article, Dr. Fein lamented that the language of the marketplace had invaded health care and was poised to shift perceptions, as physicians became “providers” and their patients “consumers.”

“Medical care is not measured solely by the number of fractures set, hernias repaired, and appendixes removed, but also by the amount of comfort, concern, and compassion provided,” he wrote. “I want physicians — as well as more Americans — to speak the language that addresses the unfinished agenda of equity and decency in the distribution of health care.”

Allan Brandt, a history of medicine professor at Harvard Medical School who formerly was dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, said that “unlike some academics, there was absolutely no separation between his values and the programs and policies and social issues that he advocated for.”

Dr. Fein, he added, “had an incredible moral compass. In that sense he set a standard that colleagues like myself try to emulate.”

Born in New York City, Rashi Fein was the older of two intellectually accomplished brothers. Leonard Fein of Watertown, who died in August, was an activist and influential writer about Jews and Judaism.

Their father was a Jewish history professor whose work brought the family to several cities in the United States and Canada. Their mother taught in elementary schools.

Dr. Fein graduated from high school in Bridgeport, Conn., where he also studied briefly at a community college before serving in the Navy at the end of World War II.

After the war, he went to Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, from which he graduated with a bachelor’s in economics in 1948 and a doctorate in political economy in 1956. By then he was teaching at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

In 1949, he married Ruth Breslau, a graduate student at Johns Hopkins whom he met through Zionist youth organizations.

The family moved to the Washington, D.C., area when Dr. Fein joined the Kennedy administration, and remained when he became a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. In 1968, he took a faculty position at Harvard. For several years, beginning in the mid-1990s, he also chaired the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s National Advisory Committee for its Scholars in Health Policy Research program.

He wrote several books, beginning with “Economics of Mental Illness” in 1958 and concluding with “Learning Lessons: Medicine, Economics, and Public Policy,” in 2010.

“As a teacher he was a source of rock-solid advice in addition to sharing his scholarship,” said Joel Kavet, who had been a student of Dr. Fein’s and spent much of his career as a health administrator and health care planner. “A lot of us who had the benefit of his guidance look back now and among us the comment overall is, ‘He made a difference in my professional life.’ ”

A service was held Wednesday for Dr. Fein, who in addition to his wife, Ruth, and his son, Alan, leaves another son, Michael of Newton; a daughter, Karen of Sandwich; and four grandchildren.

“Someone said to me, ‘The thing about your dad is he was fair,’ ” Michael said. “I thought about that and, aside from his accomplishments and the things he worked on and had done in his life, he was concerned about fairness in the world. Fairness specifically in health care, but he was also very fair in his personal dealings with people.”

Dr. Fein, he said, skillfully mixed intellect with a common touch.

“He made information that was very important, but sometimes very complex, accessible to a variety of audiences in a variety of ways, and across generations as well,” Karen said. “He was good at telling a story in a way that lots of different people could hear it.”

Her father, she added, “was a humble man. We all have egos, but his was minimal at best. For anyone to spend most of his life so passionately trying to make a difference, I think that’s to be lauded.”

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)