China Jurassic fossil discovery sheds light on bird origin

Chinese Academy of Sciences Headquarters

video:

3D Reconstruction of Baminornis zhenghensis.

view moreCredit: Video by Ren Wenyu

A research team led by Professor WANG Min from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences has discovered two bird fossils in Jurassic-era rocks from Fujian Province in southeast China. These rocks date back approximately 149 million years. The fossils fill a spatiotemporal gap in the early evolutionary history of birds and provide the evidence yet that birds were diversified by the end of the Jurassic period.

This study was published in Nature.

Birds are the most diverse group of terrestrial vertebrates. Certain macroevolutionary studies suggest that their earliest diversification dates back to the Jurassic period (approximately 145 million years ago). However, the earliest evolutionary history of birds has long been obscured by a highly fragmentary fossil record, with Archaeopteryx being the only widely accepted Jurassic bird.

Although Archaeopteryx had feathered wings, it closely resembled non-avialan dinosaurs, notably due to its distinctive long, reptilian tail—a stark contrast to the short-tailed morphology of modern and Cretaceous birds. Recent studies have questioned the avialan status of Archaeopteryx, classifying it as a deinonychosaurian dinosaur, the sister group to birds. This raises the question of whether any unambiguous records of Jurassic birds exist.

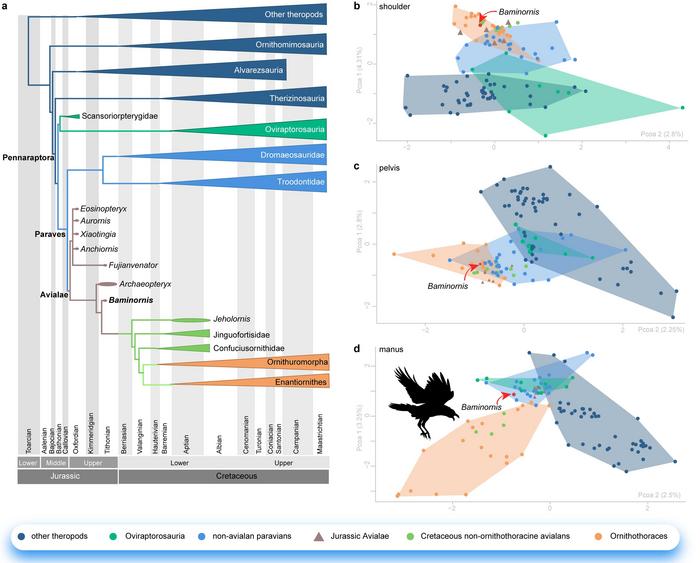

In this study, the researchers named one of the two fossils Baminornis zhenghensis. This fossil displays a unique combination of features, including derived ornithothoracine bird-like shoulder and pelvic girdles, as well as a plesiomorphic hand structure resembling that of non-avialan dinosaurs. These characteristics highlight the role of mosaic evolution in early bird development. Notably, Baminornis zhenghensis has a short tail ending in a compound bone called the pygostyle, a feature also observed in living birds.

"Previously, the oldest record of short-tailed birds is from the Early Cretaceous. Baminornis zhenghensis is the sole Jurassic and the oldest short-tailed bird yet discovered, pushing back the appearance of this derived bird feature by nearly 20 million years," said Prof. WANG, the lead and corresponding author of the study.

The researchers used several methods to explore the position of Baminornis zhenghensis in the evolutionary tree of birds. The results showed that Baminornis zhenghensis was only just derived than Archaeopteryx and it represents one of the oldest birds.

“If we take a step back, and reconsider the phylogenetic uncertainty of Archaeopteryx, we do not doubt that Baminornis zhenghensis is the true Jurassic bird,” said Dr. ZHOU Zhonghe from IVPP, co-author of the study.

The second fossil is incomplete, consisting solely of a furcula. The researchers performed geometric morphometric and phylogenetic analyses to explore its relationship with other non-avialan and avialan theropods. Interestingly, the results supported the referral of this furcula to Ornithuromorpha, a diverse group of Cretaceous birds. Given its poor preservation, however, the team refrained from naming a new taxon based on this single bone, and its placement within birds needs further fossil evidence.

Figure 1. Photograph and interpretive line drawing of the 150-million-yaer-old bird Baminornis zhenghensis

The evolutionary tree showing the position of Baminornis zhenghensis, and the morphometric space illustrating the modular evolution of different body parts

Figure 2. The evolutionary tree showing the position of Baminornis zhenghensis, and the morphometric space illustrating the modular evolution of different body parts

Figure 3. A possible Jurassic ornithuromorph furcula from the 150-million-yaer-old Zhenghe Fauna

Credit

Image by WANG Min

Figure 4. Life reconstruction of the Jurassic bird Baminornis zhenghensis from the Zhenghe Fauna

Credit

Image by ZHAO Chuang

Journal

Nature

Article Title

Earliest short-tailed bird from the Late Jurassic of China

Article Publication Date

12-Feb-2025