NEW YORK (RNS) — Swami Vivekananda founded New York's first ashram. He was feted on what would have been his 162nd birthday.

Congregants attend a birthday commemoration service for Swami Vivekananda at the Vedanta Society of New York, Sunday, Jan. 12, 2025, in Manhattan.

(RNS photo/Richa Karmarkar)

Richa Karmarkar

January 13, 2025

NEW YORK (RNS) — The Vedanta Society of New York is easy to miss. The center of worship, housed in a plain-old brownstone on the Upper West Side, has hosted dozens of monks, lamas and other “spiritual celebrities” over more than 100 years — all thanks to Swami Vivekananda, the young monk who brought the ancient Hindu spiritual wisdom to the city.

Vivekananda was born 162 years ago in Kolkata, India. Often referred to as “America’s first guru,” Vivekananda whose birth name was Narendra Nath Dutta, founded the Vedanta Society of New York in 1894, one year after landing in the U.S. It became the very first ashram of its kind outside of India.

“He said New York is ‘the purpose’ of America,” said Swami Sarvapriyananda, the presiding minister of the center. “That spirit, that vibrancy, the dynamism, the ability to execute and achieve, he noticed it, and he sought to channel it in a spiritual direction.”

About 80 New Yorkers, including Hindus, Christians, Buddhists and others of any or no label, piled into the center on Sunday (Jan. 12) to celebrate the life of the pioneer who opened the door to a wave of Indian wisdom and teachers in the West.

Vivekananda, whose given name combines the Sanskrit words for “conscience” and “bliss,” was 30 years old when he traveled to Chicago to speak at the Parliament of the World’s Religions as its first Hindu Indian delegate, where he gave a historic speech that emphasized the Vedantic Hindu teaching of coexistence and non-sectarianism.

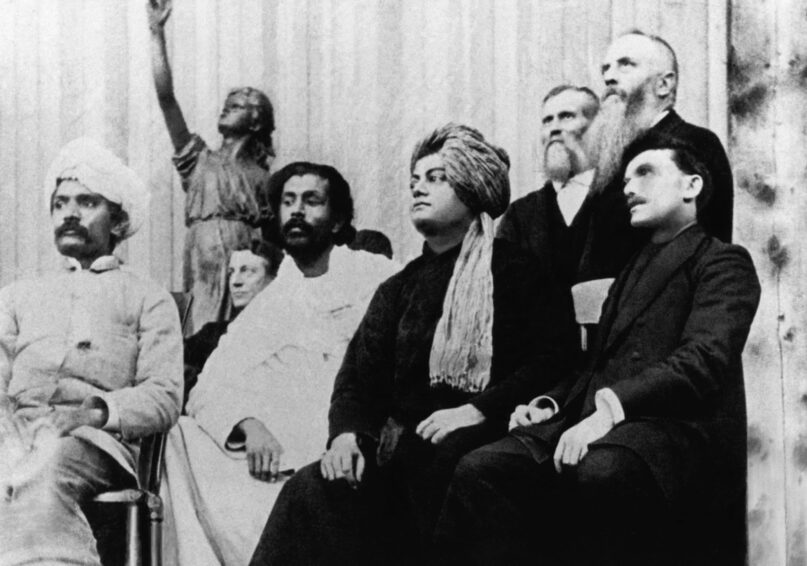

Swami Vivekananda, seated second from right, at the Parliament of the World’s Religions, Sept. 11, 1893, in Chicago. (Photo courtesy Creative Commons)

“So large a mission to perform, yet like a child was he,” sang the congregants from a Vedanta hymn book at the beginning of Sunday’s service. “Into a strange new country tossed, often hungry, often lost, improvident of time or cost, but it was meant to be.”

RELATED: New film depicting ‘hero’s journey’ of Swami Vivekananda comes to PBS

Swami Sarvapriyananda, whose name is a combination of “all-loving” and “bliss,” spoke for an hour about his predecessor, who, he said, was a sporty “life of the party” and who at age 18 asked bluntly to the gurus around him: “Have you seen God?”

As the story goes, Sri Ramakrishna, the guru who took Vivekananda in, replied: “Yes, I have. And you can, too.”

Vivekananda soon became one of the 16 direct disciples of the Ramakrishna Order: a mission of the Vedanta spiritual tradition that often discusses existence, the universe and the interconnectedness of all beings as told in the Vedas. But Vivekananda was different from the rest, said Sarvapriyananda. It was simply predestined, or “in his bones,” to spread Ramakrishna’s teachings to the rest of the world, rather than remaining spiritually introspective as he may have desired.

For the 10 years Vivekananda was a guru, or spiritual teacher, he penned many of Ramakrishna’s teachings in English and started dozens of initiatives in India and the U.S. geared toward advancing education for women and children.

“He built this bridge between East and West,” said Sarvapriyananda, who added that thousands have been “pulled from depression and meaninglessness” after reading his texts. “He represented the best of the past, present and future. In every generation, people will always find him.”

Portraits of Swami Vivekananda, from left, his guru Ramakrishna, and Sarada Devi are displayed at the Vedanta Society of New York, Sunday, Jan. 12, 2025, in Manhattan. (RNS photo/Richa Karmarkar)

Diane Crafford, the center’s president since 2012, said Vivekananda’s teaching that “each soul is potentially divine” resonated more with her than the Anglican church of her hometown of London. After her late husband, also a past president, introduced her to the Ramakrishna mission in the ’70s, the rest was history.

“I think anybody who’s exposed to him and his teachings in the West has to see what I saw, which was somebody who could answer questions that the Western religions don’t,” said Crafford. “They can draw you into a way of thinking about yourself and about others that you haven’t thought about before.”

Vedanta’s teachings can give you solace, she added. And especially in New York, where dozens of different personalities are interacting daily, “it really does help us to find our better angels, to examine our behavior with each other. I can look at you and say, ‘What’s in you is in me.'”

A longtime follower of Vedanta, Arindam Mukhopadhyay has been attending services as regularly as he can with his schedule as a banker. Though he was introduced to the Ramakrishna Mission through his family back in Kolkata more than 40 years ago, he was then a kid “rolling his eyes” through prayers and lectures.

Swami Sarvapriyananda. (Photo courtesy Vedanta Society of New York)

But “as you grow, you actually understand the philosophy behind everything,” said Mukhopadhyay, who grew up not far from the mission’s headquarters. “It’s no more worship. You move from worship to what it actually means for you to be a better human being, whether eventually you get to meet God, whether you completely understand the non-duality, or not. But I think it’s just a journey towards the deeper thinking.

“Nobody knows whether there’s an afterlife, but at least the exercise to get there makes you a better person,” he added.

Sarvapriyananda, who became spiritual head of the society in 2017, also came from Kolkata. The charismatic and humorous leader, who has since given TedX talks and is often swarmed by followers at airports, is known to many. As Crafford remarked, “No other center has a swami like Sarvapriyananda.”

“Vivekanda always insisted on originality,” he told RNS. “You can practice Vedanta or your own path, whichever path of it, and you can make it your own. You should make it your own. You should leave your particular stamp upon it.”

Sarvapriyananda became a monk in the order in 1994. But similar to Vivekananda, he felt called to share this wisdom with the world and become the public-facing teacher he is today.

“For me, the beginning was a kind of a private spirituality,” he said. “I wanted to realize God. I wanted to meditate. I wanted to be this monk. I wanted to achieve enlightenment and the world.

“But Vivekananda showed that if Vedanta is at all true, then there is one divine reality. You are not cut off from the rest of the world. So the teachings about service, spiritualizing our actions in the world, of being of use to others, the other is not really an other — one powerful insight of Vivekananda is that a private spirituality is not very spiritual after all.”

People wait outside the Vedanta Society of New York, Sunday, Jan. 12, 2025, in Manhattan. (RNS photo/Richa Karmarkar)

.png)

.png)