SCI-FI-TEK-70YRS IN THE MAKING

The Conversation

January 10, 2025

Inside the target chamber at the National Ignition Facility, where researchers work on getting higher energy outputs from fusion power. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC, and the Department of Energy − National Ignition Facility

The way scientists think about fusion changed forever in 2022, when what some called the experiment of the century demonstrated for the first time that fusion can be a viable source of clean energy.

The experiment, at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, showed ignition: a fusion reaction generating more energy out than was put in.

In addition, the past few years have been marked by a multibillion-dollar windfall of private investment in the field, principally in the United States.

But a whole host of engineering challenges must be addressed before fusion can be scaled up to become a safe, affordable source of virtually unlimited clean power. In other words, it’s engineering time.

As engineers who have been working on fundamental science and applied engineering in nuclear fusion for decades, we’ve seen much of the science and physics of fusion reach maturity in the past 10 years.

But to make fusion a feasible source of commercial power, engineers now have to tackle a host of practical challenges. Whether the United States steps up to this opportunity and emerges as the global leader in fusion energy will depend, in part, on how much the nation is willing to invest in solving these practical problems – particularly through public-private partnerships.

Building a fusion reactor

Fusion occurs when two types of hydrogen atoms, deuterium and tritium, collide in extreme conditions. The two atoms literally fuse into one atom by heating up to 180 million degrees Fahrenheit (100 million degrees Celsius), 10 times hotter than the core of the Sun. To make these reactions happen, fusion energy infrastructure will need to endure these extreme conditions.

Fusion reactions fuse together two atoms, releasing enormous amounts of energy.

There are two approaches to achieving fusion in the lab: inertial confinement fusion, which uses powerful lasers, and magnetic confinement fusion, which uses powerful magnets.

While the “experiment of the century” used inertial confinement fusion, magnetic confinement fusion has yet to demonstrate that it can break even in energy generation.

Several privately funded experiments aim to achieve this feat later this decade, and a large, internationally supported experiment in France, ITER, also hopes to break even by the late 2030s. Both are using magnetic confinement fusion.

Challenges lying ahead

Both approaches to fusion share a range of challenges that won’t be cheap to overcome. For example, researchers need to develop new materials that can withstand extreme temperatures and irradiation conditions.

Fusion reactor materials also become radioactive as they are bombarded with highly energetic particles. Researchers need to design new materials that can decay within a few years to levels of radioactivity that can be disposed of safely and more easily.

Producing enough fuel, and doing it sustainably, is also an important challenge. Deuterium is abundant and can be extracted from ordinary water. But ramping up the production of tritium, which is usually produced from lithium, will prove far more difficult. A single fusion reactor will need hundreds of grams to one kilogram (2.2 lbs.) of tritium a day to operate.

Right now, conventional nuclear reactors produce tritium as a byproduct of fission, but these cannot provide enough to sustain a fleet of fusion reactors.

So, engineers will need to develop the ability to produce tritium within the fusion device itself. This might entail surrounding the fusion reactor with lithium-containing material, which the reaction will convert into tritium.

To scale up inertial fusion, engineers will need to develop lasers capable of repeatedly hitting a fusion fuel target, made of frozen deuterium and tritium, several times per second or so. But no laser is powerful enough to do this at that rate – yet. Engineers will also need to develop control systems and algorithms that direct these lasers with extreme precision on the target.

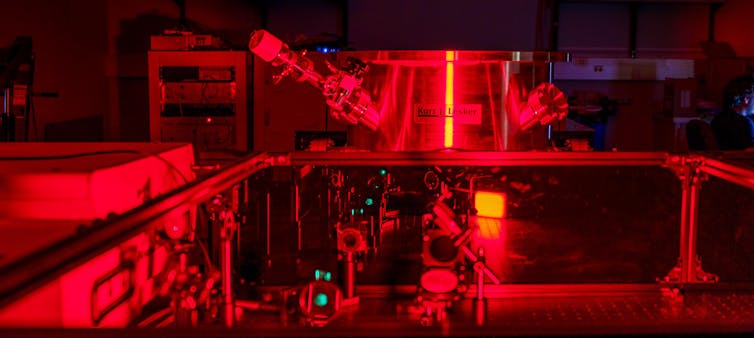

A laser setup that Farhat Beg’s research group plans to use to repeatedly hit a fusion fuel target. The goal of the experiments is to better control the target’s placement and tracking. The lighting is red from colored gels used to take the picture. David Baillot/University of California San Diego

Additionally, engineers will need to scale up production of targets by orders of magnitude: from a few hundreds handmade every year with a price tag of hundreds of thousands of dollars each to millions costing only a few dollars each.

For magnetic containment, engineers and materials scientists will need to develop more effective methods to heat and control the plasma and more heat- and radiation-resistant materials for reactor walls. The technology used to heat and confine the plasma until the atoms fuse needs to operate reliably for years.

These are some of the big challenges. They are tough but not insurmountable.

Current funding landscape

Investments from private companies globally have increased – these will likely continue to be an important factor driving fusion research forward. Private companies have attracted over US$7 billion in private investment in the past five years.

Several startups are developing different technologies and reactor designs with the aim of adding fusion to the power grid in coming decades. Most are based in the United States, with some in Europe and Asia.

While private sector investments have grown, the U.S. government continues to play a key role in the development of fusion technology up to this point. We expect it to continue to do so in the future.

It was the U.S. Department of Energy that invested about US$3 billion to build the National Ignition Facility at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in the mid 2000s, where the “experiment of the century” took place 12 years later.

In 2023, the Department of Energy announced a four-year, $42 million program to develop fusion hubs for the technology. While this funding is important, it likely will not be enough to solve the most important challenges that remain for the United States to emerge as a global leader in practical fusion energy.

One way to build partnerships between the government and private companies in this space could be to create relationships similar to that between NASA and SpaceX. As one of NASA’s commercial partners, SpaceX receives both government and private funding to develop technology that NASA can use. It was the first private company to send astronauts to space and the International Space Station.

Along with many other researchers, we are cautiously optimistic. New experimental and theoretical results, new tools and private sector investment are all adding to our growing sense that developing practical fusion energy is no longer an if but a when.

George R. Tynan, Professor of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, University of California, San Diego and Farhat Beg, Professor of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, University of California, San Diego

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Energetic particles could help to control plasma flares at the edge of a tokamak

A team of international researchers led by the Plasma Science and Fusion Technology Laboratory of the University of Seville, have demonstrated the key role that energetic particles play in the stability of a tokamak plasma edge.

University of Seville

image:

3D visualization of an ELM in the ASDEX Upgrade tokamk as simulated with the MEGA code. The tokamak volue is colored according to the ELM structure. TheELM interacts with the energetic particle whose orbit is shown in green.

view moreCredit: Figure adapted from J. Dominguez-Palacios et al., Nat. Phys. (2024), under a Creative Commons license CC BY 4.0, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The development of sustainable energy sources that can satisfy the world energy demand is one of the most challenging scientific problems. Nuclear Fusion, the energy source of stars, is a clean and virtually unlimited energy source that appears as a promising candidate.

The most promising fusion reactor design is based on the tokamak concept which uses magnetic fields to confine the plasma. Achieving high confinement is key to the development of nuclear fusion power plants and is the final aim of ITER, the largest tokamak in the world currently under construction in Cadarache (France). The plasma edge stability in a tokamak plays a fundamental role in plasma confinement. In present-day tokamaks, edge instabilities, magnetohydrodynamic waves known as ELMs (Edge Localized Modes), lead to significant particle and energy losses, like solar flares on the edge of the Sun. The particle and energy losses due to ELMs can cause erosion and excessive heat fluxes onto the plasma facing components, at levels unacceptable in future burning plasma devices.

Energetic (suprathermal) particles constitute an essential source of momentum and energy, especially in future burning plasmas. They must be well confined to guarantee a self-sustaining fusion reaction. An international collaboration has studied the impact of energetic ions on these ELMs. They have combined experiments, modelling and simulations to understand the behaviour of ELMs in the presence of energetic particles. The measurements were obtained by the team at the ASDEX Upgrade tokamak, a fusion device located at the Max Planck Institute for Plasma Physics (Garching, Germany). The simulations were done using a hybrid code named MEGA, which calculates the self-consistent interaction between the ELMs and energetic particles. Comparison of the modelling results to the experimental data provides a new physics understanding of ELMs in the presence of energetic particles. The results indicate that the spatio-temporal structure of ELMs is largely affected by the energetic particle population and indicate that the interaction mechanism between ELMs and energetic particles is a resonant energy exchange between them.

This interaction mechanism helps to qualitatively understand the striking similarities between the experimental signatures of ELMs visible in magnetic diagnostics and in fast-ion loss detectors. This experimental and computational work, which has been done within the framework of the European fusion consortium EUROfusion, has recently been published in Nature Physics.

“In our publication, we demonstrate that energetic ion kinetic effects can alter the spatio-temporal structure of the edge localized modes. The effect is analogous to a surfer riding the wave. The surfer leaves footprints on the wave when riding it. In a plasma, the energetic particle interacts with the MHD wave (the ELM) and can change its spatio-temporal pattern. Our results can have important implications for the optimization of ELM control techniques. For instance, we could use energetic particles as active actuator in the control of these MHD waves “, says main author Jesús José Domínguez-Palacios Durán.

This is a groundbreaking work, that provides, for the first time, a detailed understanding of the interaction between energetic ions and ELMs. The results indicate that, for ITER, a strong energy and momentum exchange between ELMs and energetic ions is expected.

This work has received funding from the European Research Council, EUROfusion Consortium, Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities and Junta de Andalucía.

Journal

Nature Physics

Method of Research

News article

Subject of Research

Not applicable

Article Title

Effect of energetic ions on edge-localized modes in tokamak plasmas

Article Publication Date

6-Jan-2025

Students and faculty to join research teams this spring at Department of Energy National Laboratories and a fusion facility

Selected undergraduate students and faculty will participate in unique workforce development programs at the national laboratories and a fusion facility

DOE/US Department of Energy

WASHINGTON, D.C. - A diverse group of 164 undergraduate students and six faculty will participate in unique workforce development programs at 11 of the nation’s national laboratories and a fusion facility during Spring 2025.

This opportunity is part of a continuing effort by the Department of Energy (DOE) to ensure the nation has a strong, sustained workforce trained in the skills needed to address the energy, environment, and national security challenges of today and tomorrow.

“The Department of Energy is proud to offer opportunities to students and teachers to learn about DOE, the national labs, and science as a discipline,” said Harriet Kung, DOE Office of Science’s Deputy Director for Science Programs. “When students are able to experience working in a laboratory, they have a better understanding of what their careers could be. We are excited to encourage new researchers on their paths to helping us solve the world’s challenges.”

The spring cohort includes 135 two- and four-year undergraduate students and 29 community college students. They are part of the Science Undergraduate Laboratory Internships (SULI) and Community College Internships (CCI) programs, respectively. These students, 29% of which are from Minority Serving Institutions (MSIs), will work directly with national lab scientists and engineers on research and technology projects.

In addition, the six college and university faculty members selected will collaborate with national lab research staff on projects of mutual interest through the Visiting Faculty Program (VFP). These faculty represent six institutions, 50% of which are MSIs, including one HBCU (Historically Black Colleges and Universities).

SULI, CCI, and VFP participants are selected by the DOE national laboratories and facilities from a diverse pool of applicants from academic institutions around the country. The programs are managed by the Office of Workforce Development for Teachers and Scientists (WDTS) in the DOE Office of Science. For more information, visit the Office of Workforce Development for Teachers and Scientists (WDTS) homepage.

A list of recipients can be found at https://science.osti.gov/wdts/About/Laboratory-Participants.

No comments:

Post a Comment