New York governor sets out vision for nuclear backbone

The Nuclear Reliability Backbone initiative unveiled by Kathy Hochul in her annual State of the State address includes plans for 4 GWe of new nuclear capacity in addition to plans for 1 GWe announced last year.

_43820.jpg)

The initiative is one of more than 200 included in the newly released 2026 State of the State Book, which says: "As New York transitions to a zero-emission electric grid, the State must ensure reliable and cost-effective baseload power to keep homes, businesses, and critical infrastructure running at all hours. Governor Hochul will ensure that New York State leads in the race to harness safe and reliable advanced nuclear energy to power homes and businesses with zero-emissions electricity for generations to come.

"To catalyse progress towards those goals, the Governor will advance a new initiative, the Nuclear Reliability Backbone, directing State agencies to establish a clear pathway for additional advanced nuclear generation to support grid reliability. The Nuclear Reliability Backbone will be developed by a new Department of Public Service process to consider, review, and facilitate a cost-effective pathway to 4 gigawatts of new nuclear energy that will combine with existing nuclear generation and the New York Power Authority's previously announced 1 gigawatt project, to create an 8.4 gigawatt 'backbone' of reliable energy for New Yorkers.

"This effort will provide firm, clean power that complements renewable energy resources and reduces reliance on fossil fuel generation. By creating a stable foundation of always-on energy, the Backbone will allow renewable resources to operate more efficiently and flexibly. Together, these actions will support a resilient, flexible, and zero-emission grid that meets New York’s growing energy needs."

An additional initiative will be launched to develop a "skilled, in-state nuclear workforce through coordinated education and training pathways". The NextGen Nuclear New York initiative will aim to align educational curriculums, credentials, and career pathways with industry needs, as well as supporting workforce transitions for existing energy workers and increasing public awareness of nuclear career opportunities.

In June, Hochul directed the New York Power Authority - the state's public electric utility - to develop at least 1 GWe of advanced nuclear capacity in Upstate New York. Earlier this month, it announced it had received a "robust" response to two October 2025 Requests for Information seeking potential host communities and development partners, with 23 responses from potential developers or partners, and eight responses from Upstate New York communities.

John Carlson, Senior Northeast Regional Policy Manager at global nonprofit organisation Clean Air Task Force, said the action comes at a "pivotal moment" for New York. In December, an updated plan released by the state's Energy Planning Board recognised a continuing role for nuclear to help the state meet its overall energy needs over the next 15 years.

"By tasking the Public Service Commission to develop the market frameworks to enable these new builds, Goveror Hochul is ensuring that ratepayer interests and affordability are at the forefront while building the clean, economical grid of the future, one that also supports workforce development, strengthens municipal tax bases, and delivers these economic benefits to local communities," he said.

Four nuclear reactors - all operated by Constellation Energy - currently provide some 21.4% of all New York's electricity, and 41.6% of its carbon-free electricity, according to information from the Nuclear Energy Institute.

Impact assessment process begins for Canadian new-build

Ontario Power Generation has submitted the Initial Project Description for a new nuclear plant at Wesleyville near Port Hope, a regulatory milestone marking the first step in the impact assessment process.

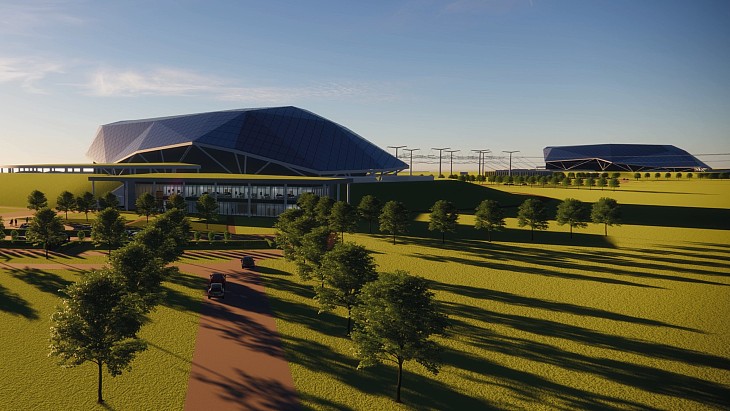

_45278.jpg)

The Impact Assessment Agency of Canada (IAAC) and the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) are inviting public comments on the initial description of the project which has now been published on the agency's website, along with a summary in English and French. The deadline for comments is 11 February.

The Ontario government formally asked Ontario Power Generation (OPG) to explore opportunities for new nuclear energy generation at Wesleyville in January last year, after the local municipality and Indigenous communities expressed their support. The OPG-owned site has been municipally zoned and maintained for electricity generation for more than 50 years. OPG has identified the potential to construct and operate nuclear generating stations on both the eastern and western portions of the site.

The New Nuclear at Wesleyville Project would provide up to 10,000 megawatts of new nuclear generating capacity - enough to power the equivalent of 10 million homes, according to OPG - and operate for 78 years. No reactor technology has yet been selected, but OPG has considered several technologies as part of so-called Plant Parameter Envelope approach which will be used for site licensing. These include pressurised water reactor technology (Westinghouse’s AP1000 and EDF’s EPR); pressurised heavy water reactor (CANDU) technology (Atkins Realis’ CANDU MONARK); and boiling water reactor technology (GE-Hitachi’s BWRX-300).

The Impact Assessment Agency of Canada-led Impact Assessment process will include an assessment of potential impacts and explore how adverse effects could be mitigated during site preparation, construction, operation, and decommissioning of the plant. The current timeline for the project outlined in the Initial Project Description envisages site preparation beginning in 2030 with construction starting in 2033 and the first unit coming online in 2040.

OPG acknowledges that Port Hope and the New Nuclear at Wesleyville site are within the shared traditional and treaty territory of the Chippewa and Michi Saagiig Anishinaabeg, collectively known as the Williams Treaties First Nations (WTFNs), and said it worked closely with them to ensure their collaborative input to the document. "The Initial Project Description (IPD) includes perspectives from MS-WTFN community members including Elders and those who have traditional knowledge of the area. The IPD also incorporates early input from the Municipality of Port Hope, where the proposed project is located, and perspectives gathered through OPG’s early engagement efforts in the community," the company said.

Project Phoenix report backs SMR use in Slovakia

The Project Phoenix study, carried out by Sargent & Lundy with Slovakia's Ministry of Economy and nuclear energy operator Slovenské elektrárne, aimed to assess the country's readiness and potential to host small modular reactors (SMRs), with a focus on four specific locations - Bohunice, Mochovce, Vojany, and US Steel Košice.

According to Slovenské elektrárne the evaluation used International Atomic Energy Agency recommendations including external risks, geological conditions, environmental and safety factors and site suitability. As well as the country's general suitability, the study said that all four sites met the baseline criteria for SMR deployment.

Joshua Best, senior manager at company Sargent & Lundy, said: "The report affirms that Slovakia is strategically situated to deploy SMRs, with several mature, safe, and secure SMR technologies available that align with the country's needs and goals. All candidate sites assessed are viable, and Slovakia is primed to take the next steps should they choose to proceed."

The next steps are expected to be the development of a regulatory framework, detailed site investigations and public information and consultation. Project Phoenix was launched in 2022 with the aim of supporting energy security and climate goals by creating pathways for coal-to-SMR power plant conversions while retaining local jobs through workforce retraining.

Szabolcs Hodosy, First State Secretary of the Ministry of Economy of the Slovak Republic, said: "It is crucial that such decisions are based on expert analyses, international safety standards, and transparent dialogue with the public. I am glad that a new area of nuclear energy is taking shape in Slovakia, where we can make use of our many years of experience and thus also outline a clear direction for future generations of 'nuclear experts'. Nuclear energy is experiencing its renaissance, and we must take timely steps - both in education and in preparing infrastructure, as well as in promoting support for nuclear energy across all platforms - so that we can then share the benefits of nuclear energy production at both the national and regional levels."

Branislav Strýček, Chairman and CEO of Slovenské elektrárne, said: "Small modular reactors represent a strategic opportunity for Slovakia. They can strengthen our energy security, support decarbonisation, and bring new investment to the regions. The study confirms that we not only have suitable sites, but also the technical know-how and experience to build on."

US Deputy Chief of Mission in the Slovak Republic, Heather Rogers, said: "Project Phoenix demonstrates Slovakia’s robust nuclear energy experience, infrastructure, regulatory framework, and industrial base provide a strong platform for early deployment of small modular reactor technologies under the highest international safety and security standards. We are delighted to support Slovakia's efforts to strengthen energy resilience and shared prosperity and look forward to continued collaboration."

Slovenské elektrárne says that SMRs could be operational in the country from as early as 2035. Slovakia currently has five nuclear reactors generating about half its electricity, with one more reactor under construction. The first two, at Bohunice, went into commercial operation in 1984 and 1985, respectively, while Mochovce 1 and 2 were connected to the grid in 1998 and 1999, respectively. Construction of Mochovce 3 and 4 began in 1986 but was halted in 1992. It was later restarted and Mochovce 3 entered service in 2023, with work continuing on Mochovce 4.

The Slovak government also has plans for a new large-scale unit. It officially approved plans in May 2024 for a 1.2 GWe unit near the existing Bohunice nuclear power plant. In September 2025 ministers approved wording for a proposed intergovernmental agreement with the USA "on the construction of a new nuclear unit ... which will be state-owned and will have an output of more than 1,000 MW" and Slovakia's Prime Minister Robert Fico is meeting US President Donald Trump this weekend and set to sign the agreement, according to multiple media reports, including Euronews.

Licensing of Newcleo's SMR progresses in France

_77716.jpg)

Prior to applying for authorisation to construct a nuclear facility in France, a project developer may submit all or part of the design of its nuclear installation to the Autorité de Sûreté Nucléaire et de Radioprotection (ASNR), together with the safety approach, safety functions, structures, systems, components, or any other elements relevant to the proposed facility’s nuclear safety programme.

"The ASNR's independent review will enable Newcleo to identify safety improvements and to strengthen its application for authorisation to construct the facility," the company said.

"This major milestone is the result of years of engineering and R&D work, reinforced by a technical dialogue with the ASNR," Stefano Buono, CEO and founder of Newcleo, said. "As we prepare to apply for authorisation to build a nuclear power installation in 2027, we are also establishing a framework that will serve as a foundation for our interactions with other foreign nuclear safety authorities and to expand into additional markets. We support our technical validation efforts through a world-class R&D programme located at the ENEA Brasimone Research Centre in Italy, where we operate and are building 16 R&D facilities that generate data to validate our parameters and support our forthcoming qualification files."

In December 2024, Newcleo submitted its Safety Option File to France's nuclear safety regulator for its fuel assembly testing facility. The ASNR's official opinion on the submitted safety options will contribute to securing the application for authorisation to construct such a facility.

"The ASNR's review of both nuclear safety programme files will allow Newcleo to consolidate the applications for authorisation to build these two nuclear installations, which are expected to be submitted to the relevant French Ministry before the end of 2027," Newcleo said. "The applications for authorisation will also contain information on progress related to nuclear safeguards with Euratom. They will further be subject to review by the French national security authorities regarding requirements to ensure adequate protection of the installations against potential malicious acts."

Newcleo officially initiated its safeguards-by-design engagement with Euratom, the regulatory body overseeing nuclear safeguards within the European Union, for its lead-cooled fast reactor (LFR) in December last year. A mandatory requirement under the new Commission Regulation (Euratom) 2025/974, which came into effect on 6 July 2025, safeguards-by-design refers to the process where operators of new or modified nuclear facilities integrate Euratom safeguards considerations into the design phase and formally provide this design information to the European Commission.

Paris-headquartered Newcleo's delivery roadmap sees the first non-nuclear precursor prototype of its LFR being ready by 2026 in Italy and the first reactor operational in France as early as 2032, while the final investment decision for the first commercial power plant is expected around 2029. At the same time, Newcleo will directly invest in a mixed uranium/plutonium oxide (MOX) plant to fuel its reactors. It has initiated site acquisition and public consultation processes in France for the MOX fuel pilot assembly line in Nogent-sure-Seine.

"These nuclear installation projects will be subject to a mandatory public debate in France, as decided by the National Commission for Public Debate in June 2025," Newcleo noted. "This debate, to be held in 2026, is intended to involve the public in the process, gather stakeholder inputs, and contribute to decision-making on these two major nuclear projects, in line with the regulatory processes leading to the authorisations."

Skanska to produce prototype aseismic bearing for Rolls-Royce SMR

Aseismic bearings are installed beneath the plant's nuclear island to decouple the reactor building from ground motion during an earthquake. By absorbing and dissipating seismic energy, they reduce the forces transmitted to the superstructure, preserving both integrity and functionality.

The project will be delivered from Skanska's fabrications facility in Doncaster, England, and includes building a prototype of the aseismic bearing pedestal. Skanska - one of Sweden’s largest companies - is one of the world's leading project development and construction companies.

_e98d12e9.jpg)

(Image: Rolls-Royce SMR)

"Working with Skanska is a significant step forward in proving the capability of our aseismic bearing technology and demonstrating our modular approach to construction," said Ruth Todd, Rolls-Royce SMR Operations and Supply Chain Director. "By working with a trusted delivery partner, we are de-risking our 'fleet-based' approach and creating opportunities for more British and Czech suppliers to play a key role the Rolls-Royce SMR mission."

Adam McDonald, Executive Vice President at Skanska UK, added: "We'll be bringing our civil engineering, design and fabrications expertise to build and test a first-of-its-kind pre-cast bearing pedestal – a critical component for Rolls-Royce SMR in building new nuclear power generation. Over the coming months, we'll develop the prototype and run various technical trials at our Bentley Works facility in Doncaster. We are looking forward to playing our part in developing the next generation of nuclear energy."

The Rolls-Royce SMR is a 470 MWe design based on a small pressurised water reactor. It will provide consistent baseload generation for at least 60 years. Ninety percent of the SMR - measuring about 16 metres by 4 metres - will be built in factory conditions, limiting activity on-site primarily to assembly of pre-fabricated, pre-tested, modules which significantly reduces project risk and has the potential to drastically shorten build schedules.

It has been selected by both the Czech Republic and the UK governments for their respective proposed SMR programmes.

"The standardised bearing design is pre-qualified against a wide spectrum of seismic profiles, meaning the Rolls-Royce SMR can be sited nearly anywhere in the world without bespoke redesign," Rolls-Royce SMR said. "Proven in nuclear and civil applications, the aseismic bearing system aligns with international seismic codes and best practice guidelines, streamlining regulatory review and boosting stakeholder trust.

"This approach enables a flexible yet standardised SMR solution: a globally deployable plant design that adapts to local environments without compromising safety, performance, or efficiency."

Long-term graphite agreement strengthens X-energy supply chain

The 10-year framework agreement between X-energy Reactor Company and SGL Carbon LLC covers the supply of graphite for the deployment of X-energy's Xe-100 small modular reactor, with a contract to support the first deployment of the reactor at the Seadrift site in Texas and an agreement to reserve capacity for a planned 12-unit plant in Washington State.

Wiesbaden, Germany, headquartered SGL has already begun production of graphite reactor components using its NBG-18 medium-grain isotropic graphite for the first deployment of the Xe-100 under the initial contract which is worth USD100 million over three years. The proposed four-unit plant at Dow Inc's Seadrift site on the Texas Gulf Coast is being supported by the US Department of Energy's Advanced Reactor Demonstration Program.

The companies have also signed an agreement to reserve capacity and develop production readiness for the Cascade Advanced Energy Facility with Energy Northwest in Washington state, a planned 12-unit Xe-100 plant and the first of a series of Amazon and X-energy projects targeting at least 5 GWe of new nuclear energy by 2039. Graphite production for this is expected to begin in the second half of 2026.

The Xe-100 is a based on based on HTGR (high temperature gas cooled reactor) technology, using TRISO (tri-structural isotropic) particle fuel to power an 80 MWe reactor that can be scaled into a 'four-pack' 320 MWe power plant. Fine-grain graphite is a critical component: the Xe-100 uses graphite as both a neutron moderator and structural component, enabling it to operate at high temperatures while maintaining exceptional safety characteristics.

SGL has a long history in supplying graphite into nuclear applications, and has collaborated with X-energy since 2015 on the qualification of NBG-18 graphite for use in the Xe-100, leveraging SGL's experience manufacturing graphite for HTGRs.

"Scaling new nuclear requires partners who know how to execute, and have done so time and again in the world's most demanding industries," X-energy CEO Clay Sell said. "SGL brings decades of innovation in aerospace, automotive, energy, and semiconductor applications, and we are thrilled to bring that depth of experience into the new nuclear sector."

SGL Carbon CEO Andreas Klein described work done in recent years by X-energy as "groundbreaking", adding that the company is proud to be part of the "success story" as the implementation phase begins. "This is a first milestone in the development of new applications for our products and SGL Carbon's entry into a strategically important market," he said.

The agreement with SGL is the most recent in a series of announcements as X-energy builds a portfolio of suppliers to support its commercial pipeline. These include agreements with Doosan Enerbility for steel manufacturing and capacity expansion, Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power for fleet-scale deployment collaboration, and additional agreements for IG-110 fine-grain graphite.

China starts construction of innovative nuclear project

Xuwei Phase I was among 11 reactors approved by China's State Council in August 2024. China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) plans to build two 1208 MWe (net) Hualong One units and one 660 MWe high-temperature gas-cooled reactor (HTGR) unit at the site in Lianyungang, Jiangsu province. The project will be equipped with a steam heat exchange station, which will adopt the heat-to-electricity operation mode for the first time. China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) describes the project as the "world's first dual-coupling demonstration project combining a third-generation nuclear PWR and a fourth-generation nuclear HTGR".

_4735e09c.jpg)

(Image: CNNP)

At the plant - very close to CNNC's existing Tianwan plant - demineralised water will be heated by the primary steam of the Hualong One units to produce saturated steam, and the primary steam of the HTGR will be used to heat the saturated steam for the second time.

_a202a4b5.jpg)

(Image: CNNP)

A contract for the construction of the conventional islands of the three units was awarded in September last year to a consortium formed by China Energy Engineering Jiangsu Electric Power Construction No 3 Company and China National Nuclear Huachen Construction Engineering Company. Under the CNY4.2 billion (USD594 million) contract, Jiangsu Electric Power Construction No 3 Company will build the three conventional island power plants, their ancillary facilities, and the construction and installation of some 'balance of plant' components.

_812240c0.jpg)

A rendering of the Xuwei plant (Image: CNNC)

CNNC Suneng Nuclear Power Company, is the CNNC subsidiary which is the owner of the Xuwei project and responsible for project investment, construction and operation management.

Once the project is completed and put into operation, it will supply 32.5 million tonnes of industrial steam annually, with a maximum power generation of more than 11.5 billion kilowatt-hours, which can reduce the use of standard coal by 7.26 million tonnes and reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 19.6 million tonnes each year.

Arabelle turbines selected for Polish plant

_65585.jpg)

Arabelle Solutions will supply all three units of the Choczewo nuclear power plant with the steam turbine, generator including auxiliary systems, as well as key equipment of the water steam cycle including the condenser, moisture separator reheaters, low and high-pressure feedwater heaters, and feedwater and deaerating tanks. In a nuclear power plant, heat from the reactor turns water into steam, which spins a turbine and generator to produce electricity.

In total, the half-speed Arabelle steam turbine generator shaftline for the AP1000 will be 68 metres long and includes a combined high/intermediate-pressure module and three double-flow low-pressure modules for improved cycle efficiency. It will be coupled with a hydrogen and water-cooled GIGATOP 4-pole generator synchronised to the 50 Hz Polish grid.

"The selection follows a rigorous procurement process evaluating both technical and financial criteria," Bechtel said. "Arabelle Solutions will adapt its standard steam turbine design for the turbine island at the Choczewo site, with fabrication expected to begin after the Engineering, Procurement and Construction (EPC) agreement for the project is finalised."

"We are proud to partner with Bechtel and Westinghouse Electric Company to deliver the turbine hall equipment for the first nuclear power plant in Poland, contributing to providing reliable, low-carbon electricity to the country," said Arabelle Solutions CEO Catherine Cornand. "This project reflects both the trust of our partners and the commitment of our teams to carry forward our long-standing expertise and legacy of innovation to meet the world's growing energy needs."

Ed Gore, Project Director, Poland AP1000 Project, Bechtel, said: "Arabelle Solutions brings deep regional capabilities and provides opportunities for Polish producers to participate in this project. We are proud to apply Bechtel's world-class construction expertise to support the energy transition of Poland."

Dan Lipman, President of Westinghouse Energy Systems, added: "The choice of Arabelle Solutions for the project's steam turbine generator is a strong complement to the AP1000 reactor. Having such a major European supplier involved in the project underscores Westinghouse-Bechtel consortium 'Buy Where We Build' philosophy and our commitment to having Polish companies participating throughout the entire project."

"We have chosen a partner who guarantees experience, and above all reliability and a wide chain of suppliers - largely Polish," said Marek Woszczyk, President of the Management Board of Polskie Elektrownie Jądrowe (PEJ).

In November 2022, the then Polish government selected Westinghouse AP1000 reactor technology for construction at the Lubiatowo-Kopalino site in the Choczewo municipality in Pomerania in northern Poland. An agreement setting a plan for the delivery of the plant was signed in May 2023 by Westinghouse, Bechtel and PEJ - a special-purpose vehicle 100% owned by Poland's State Treasury. The Ministry of Climate and Environment in July 2024 issued a decision-in-principle for PEJ to construct the plant. The aim is for Poland's first AP1000 reactor to enter commercial operation in 2033. The total investment costs of the project are estimated to be about EUR42 billion (USD47 billion).

EDF completed its acquisition of a portion of GE Vernova's nuclear conventional islands technology and services - including its Arabelle steam turbines - in May 2024. The transaction included the manufacturing of conventional island equipment for new nuclear power plants as well as related maintenance and upgrade activities for existing nuclear plants outside of the Americas. EDF's acquisition of the business - at that time, known as GE Steam Power - was first announced in early 2022 and the final agreement was signed in the November of that year.

German steam generators arrive in Sweden for recycling

_39670.jpg)

In 2021, PreussenElektra awarded the contract for the dismantling and disposal of a total of 16 steam generators from the Unterweser, Grafenrheinfeld, Grohnde, and Brokdorf plants to Cyclife, a subsidiary of EDF specialising in nuclear power plant decommissioning and waste management. Cyclife is responsible for the entire process, from collection at PreussenElektra plants to the upcoming treatment and the future return delivery of the processed waste.

Steam generators are the heat exchangers in pressurised water reactors (PWRs), producing the steam that turns the turbines to generate the electrical energy in the generator. PreussenElektra said the dismantling and disposal of the steam generators is one of the key projects in the dismantling of its PWRs and will take more than a decade.

The removal of all four steam generators from the reactor building at the Unterweser plant began in mid-May last year. In total, all four steam generators - each measuring 20 metres in height and weighing about 300 tonnes - were removed within four weeks, completing the project on schedule. The actual dismantling was preceded by nearly two years of planning, testing, and implementation of the necessary modifications and additions inside and outside the reactor building, as well as the individual dismantling steps of the large heat exchangers.

Unterweser - a pressurised water reactor with a gross installed capacity of 1410 MWe - operated between 1978 and 2011. It was one of seven nuclear power plants shut down in Germany in March 2011 when it lost its commercial operating licence under the 13th Amendment to the Atomic Energy Act.

_219966eb.jpg)

(Image: Mammoet)

Cyclife Sweden has now successfully completed the transport of the four steam generators from Unterweser to its new facility in Sweden.

"After several months of preparation and coordination, the four steam generators have now arrived at our facility, where they will be processed with the aim of recycling a substantial proportion of the material in our new facility which is doubling our treatment capacity here in Sweden," said Delphine Servot, managing director of Cyclife Sweden. "We worked closely with PreussenElektra throughout the project, from planning to execution, contributing expertise and resources to enable the safe and efficient transport and handling of the components."

Michael Bongartz, member of the board of PreussenElektra, added: "Following the successful shipment of the steam generators from our pilot plant in Unterweser to Sweden, we now look forward to working with Cyclife to transfer the lessons learned and experience to the upcoming steam generator projects. Upon reaching this key milestone, I would also like to express my gratitude to the on-site teams for their professionalism and collaborative spirit."

"Awarding this contract for our nuclear power plants was a strategic decision to accelerate decommissioning," said PreussenElektra CEO Guido Knott. "This will enable us to leverage synergies across all sites and consistently apply the knowledge we have gained. With Cyclife's proven expertise in managing complex decommissioning projects, this partnership sets a benchmark for safe and efficient implementation."

Cyclife says it has developed a process and facilities in Sweden for dismantling and disposing of steam generators that provides a turn-key solution for nuclear operators on retired metallic large components and scrap metal. This includes the management of their transport from/to customer or final depository, the storage on Cyclife's site before and after treatment, a volume reduction up to 95%, the characterisation of secondary waste, associated analysis and conditioning of final packages, and eventually the management of metallic reusable ingots (characterisation, free-release and selling to conventional industries).

To date, Cyclife Sweden has successfully processed more than 30 large components (steam generators, heat exchangers, etc) from Swedish, German, French and British nuclear power plants.

Tests confirm integrity of Deep Isolation disposal canister

_41144.jpg)

Disposal in deep boreholes - narrow, vertical holes drilled deep into the earth's crust - has been considered as an option for the geological isolation of radioactive wastes since the 1950s. Deep borehole concepts have been developed in countries including Denmark, Sweden, Switzerland, and the USA but have not yet been implemented.

Deep Isolation's patented technology leverages standard drilling technology using off-the-shelf tools and equipment that are common in the oil and gas drilling industry. It envisages emplacing nuclear waste in corrosion-resistant canisters - typically 9-13 inches (22-33 centimetres) in diameter and 14 feet long - into drillholes in rock that has been stable for tens to hundreds of millions of years. The drillhole - which is lined with a steel casing - begins with a vertical access section which then gradually curves until it is nearly horizontal, with a slight upward tilt. This horizontal 'disposal section' would be up to two miles (3.2 kilometres) in length and lie anything from a few thousand feet to two miles beneath the surface, depending on geology. Once the waste is in place, the vertical access section of the drillhole and the beginning of its horizontal disposal section would be sealed using rock, bentonite and other materials.

Deep Isolation's Universal Canister System (UCS) - developed in collaboration with NAC International Inc through a three-year project funded by the US Department of Energy (DOE) Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy (ARPA-E) - is designed to accommodate a range of advanced reactor waste streams, including vitrified waste from reprocessing, TRISO used fuel, and halide salts from molten salt reactors. It is compatible with modern dry storage and transport infrastructure, and meets performance and safety requirements across both borehole and mined repository options, which gives greater flexibility and reduced uncertainty in future waste disposition, the company says.

Project SAVANT (Sequential Advancement of Technology for Deep Borehole Disposal) - a two-year research initiative funded by the DOE's ARPA-E - found that Deep Isolation's UCS and borehole casing materials can sufficiently resist corrosion to safely store radioactive waste material, "further validating the design and advancing the company toward a full-scale deep borehole disposal demonstration".

Building on the project's central objective, the Project SAVANT team evaluated corrosion performance under realistic thermal, chemical, and mechanical stressors expected in a deep borehole environment. These data sets strengthen the scientific basis for Deep Isolation's UCS and reinforce confidence in the system's design life.

"This important study shows that Deep Isolation has achieved another critical milestone in the development of a safe method of disposing of radioactive nuclear waste – something the world critically needs," said Deep Isolation President and CEO Rod Baltzer. "Nuclear energy is facing a growing challenge. Global nuclear power capacity is forecast to increase by more than 300 GW by 2050, yet the world has not permanently disposed of any of the spent fuel it has created over the last 70 years. We believe our deep borehole technology will ultimately be the solution for safely and permanently disposing of nuclear waste deep underground, a solution the world needs."

"The Project SAVANT data significantly strengthens our understanding of how UCS and borehole system materials perform under the conditions expected in a deep geologic environment," said Jesse Sloane, Executive VP of Engineering at Deep Isolation. "These results demonstrate wide margins of safety for the public and reinforce the robustness of our design approach. With these results in hand, we are well positioned to advance into larger scale testing.”

Stan Gingrich, Principal Engineer at Amentum and a Project SAVANT collaborator, emphasised the importance of materials research in advancing disposal readiness. "The corrosion testing produced data representative of deep borehole disposal environments," he said. "Our collaboration with Deep Isolation, including our co-authored paper on the results of materials under high temperature and pressure conditions (presented at Waste Management Symposia 2025), underscores how phased testing can bring innovative disposal solutions closer to reality."

The project also incorporated supply chain research and cost estimation developed in partnership with the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI). These findings highlight opportunities to build domestic manufacturing pathways for canisters, casing materials, and deployment equipment that could accelerate commercial readiness and reduce lifecycle costs for future disposal facilities.

Deep Isolation said Project SAVANT supports a broader industry effort to modernise the back end of the nuclear fuel cycle. "As nations expand advanced reactor deployment, durable and predictable disposal pathways are increasingly essential to long-term planning and public confidence. The Project SAVANT findings provide new, data-driven insights that can guide future regulatory, commercial, and technical decision-making for deep borehole disposal."

Helen creating subsidiary for nuclear project

_95366.jpg)

Helen - which currently produces heat, electricity and cooling in power plants and heating plants in different parts of Helsinki - is aiming for carbon-neutral energy production during the 2030s. In September 2024, the company launched the first phase of its nuclear programme, aimed at constructing a small nuclear power plant for producing heat for Helsinki city. Its nuclear energy programme will evaluate small modular reactors (SMRs) based on proven solutions, which can be used to produce just heat or both electricity and heat. During the initial phase of its nuclear programme, Helen said it will negotiate with potential partner shareholders, evaluate plant suppliers and determine potential plant sites. The first phase of the programme is due to be completed in 2026.

The company said the new subsidiary will begin operations at the start of February. Jarmo Tanhua - who served for 17 years as CEO of Teollisuuden Voima Oyj, during which time the Olkiluoto 3 EPR was constructed in Olkiluoto - has been appointed as Chair of the Board of Helen Ydinvoima Oy, while Pekka Tolonen has been appointed CEO.

"In Finland, we have good experiences and excellent expertise in nuclear power," Tanhua said. "There is a clear need for Helen's project, and it starts from a new perspective. We want to find out whether it is possible to build and commission the first new small nuclear power plant in Finland. Of course, such a project is of great interest."

"Transferring the nuclear energy programme to its own project development company enables flexible development of the programme as an independent entity," said Helen CEO Olli Sirkka. "It also creates better conditions for the project's success by opening up opportunities for various financing and business solutions."

In November 2022, Helen announced a joint study with Finnish utility Fortum - operator of the Loviisa nuclear power plant - to explore possible collaboration in new nuclear power, especially SMRs. The companies formed a study group to explore possible synergy benefits for the two firms.

In October 2023, Helen became the first energy company to engage in cooperation with Steady Energy by signing a letter of intent aimed at enabling an investment in a small-scale nuclear power plant for the production of district heating. Valid until 2027, the agreement includes promoting the reform of the Finnish Nuclear Energy Act, applying for a siting licence and a technological permit, and fixing the contract price of the plant. It would also enable Helen to procure up to ten reactor units with an output of 50 MW from Steady Energy.

Helen announced in November last year that it had selected three potential power plant sites in Helsinki for further assessment. The sites in question are the Vuosaari and Salmisaari power plant areas and the Norrberget area in western Östersundom. With the exception of Norrberget, the sites are already being used for energy production operations and are managed by Helen.

"Currently, the project is running a competitive bidding process for plant suppliers, exploring business and partnership models, and investigating collaboration opportunities with both industry and other energy companies," Helen said. "In addition, the project is assessing the prerequisites for nuclear energy production at previously announced potential plant sites through studies and environmental impact assessments."

Operating permit for very low-level waste disposal facility in Finland

The radiation properties of this waste is not harmful to people or the environment. Very low-level waste can include, for example, protective plastics and protective clothing that have been used during maintenance outages at a nuclear power plant.

Very low-level waste has so far been disposed of in Olkiluoto's VLJ repository, which was commissioned in 1992 and consists of two rock silos, a hall connecting the two and auxiliary facilities constructed at a depth of 60-100 metres inside the bedrock.

Teollisuuden Voima Oyj (TVO) says the establishment of a new facility reduces the need to expand the operating waste repository.

Construction and operation of the facility "will not start until TVO makes the construction decision and STUK (Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority of Finland) verifies compliance with requirements through specific inspections". Operation of the facility will not start until 2028 at the earliest.

The plan is for the facility, which will be near the VLJ repository, to have a total volume of 45,200 cubic metres, with nuclear waste accounting for up to 10,000 cubic metres. TVO said: "In a soil disposal facility, very low-level waste is packaged by waste type and covered with a layer of soil." It added that although it was the first such facility in Finland, it has been a long-standing method in other parts of the world, including in Sweden.

Senior Project Manager Jari Eskola said: "The operating permit is a significant step for responsible waste management in Olkiluoto. The solution is based on high safety requirements to ensure that the final disposal of very low-level waste is implemented in a controlled manner and protecting the environment."

Finland has five operable nuclear reactors providing about one-third of its electricity. There are various schemes and plans for new small modular reactors in the country. The country is close to giving the go-ahead for operations at the Onkalo deep geological repository to permanently dispose of used nuclear fuel. This is a repository in crystalline rock with used fuel in copper canisters surrounded by a bentonite buffer at a depth of 400-430 metres.