Red coral colonies survive a decade after being transplanted in the Medes Islands

Preventing the impact of climate change on transplanted coral

News Release

University of Barcelona

image:

The study confirms the success of some actions to restore corals seized from poaching — actions promoted by the UB and the ICM (CSIC) — which have allowed both the survival of the transplanted corals and the rapid recovery of the associated coral community.

view moreCredit: MedRecover Research Group

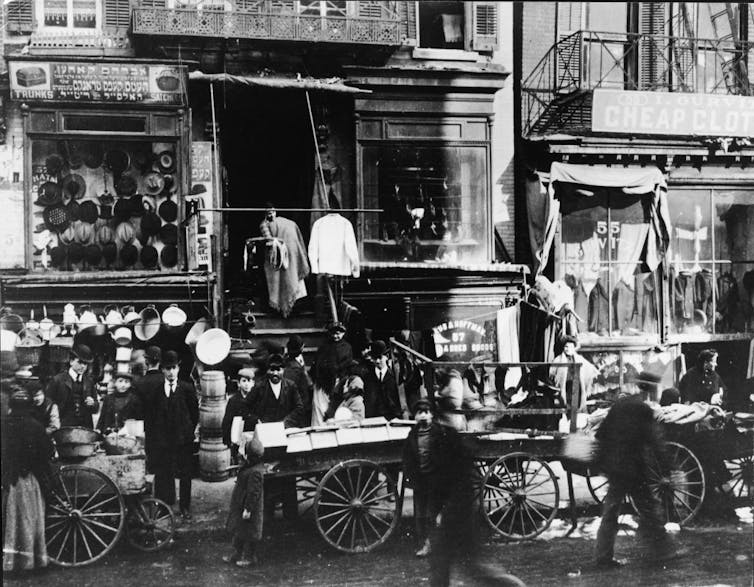

The red coral colonies that were transplanted a decade ago on the seabed of the Medes Islands have survived successfully. They are very similar to the original communities and have contributed to the recovery of the functioning of the coral reef, a habitat where species usually grow very slowly. Thus, these colonies, seized years ago from illegal fishing, have found a second chance to survive, thanks to the restoration actions of the University of Barcelona teams, in collaboration with the Institute of Marine Sciences (ICM - CSIC), to transplant seized corals and mitigate the impact of poaching.

These results are now presented in an article in the journal Science Advances. Its main authors are the experts Cristina Linares and Yanis Zentner, from the UB’s Faculty of Biology and the Biodiversity Research Institute (IRBio), and Joaquim Garrabou, from the ICM (of the Spanish National Research Centre, CSIC).

The findings indicate that actions to replant corals seized by the rural corps from poachers are effective not only in the short term — the first results were published after four years — but also in the long term, i.e. ten years after they have been initiated. Under the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2021-2030) and the European Union’s Nature Restoration Act, the paper stands out as one of the few research studies that has evaluated the success of long-term restoration in the marine ecosystem.

Transplanted colonies surviving and helping to structure the coralligenous habitat

Red coral (Corallim rubrum) poaching has been a threat even in marine protected areas and, in addition, due to the slow growth of this species, populations are still far from pristine conditions. The team’s restoration work was carried out in the Montgrí, Medes Islands and Baix Ter Natural Park, “at a depth of around 18 metres, in a little-visited area where no poaching has been observed in recent years and which, for the moment, does not seem to be affected by climate change”, explains Cristina Linares, professor at the UB’s Department of Evolutionary Biology, Ecology and Environmental Sciences.

The results of this research study, which has received funding from both the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities and the European Union’s Next Generation funds, reveal the high survival of the transplanted red coral colonies after so many years. “The restored community — i.e. the set of organisms in the environment where the transplanted coral is found — has been completely transformed in just ten years”, says Linares. “The community has also assimilated the structure expected in natural red coral communities. This reinforces the key value of habitat-generating species such as red coral, and the benefits that can grow from targeting them for conservation and restoration actions”, he continues.

Preventing the impact of climate change on transplanted coral

Rising temperatures and heatwaves caused by global change are causing mortality in populations of red coral and 50 other species in the Mediterranean. In addition, the long tradition of coral fishing for the jewellery world also threatens its colonies, which have reduced presence and a decisive ecological role in areas of difficult access and high depths. “If there is no additional impact — such as climate change —, we expect to reach a well-developed community on a much faster timescale than we originally expected”, says Yanis Zentner (UB - IRBio), predoctoral researcher and first author of the paper.

“It is a biological community with a very slow dynamic, so being able to transplant coral colonies of a certain size means ‘gaining’ a lot of time in ecological restoration. However, while the rapid transformation observed in this study is encouraging, whether this system is capable of fully restoring the functionality of a pristine coral reef remains to be seen”, warns Zentner.

Regarding red coral, it only makes sense to apply this methodology in coralligenous habitats or in caves, which is the natural habitat of the species. “In addition, it is advisable to avoid the potential impact of climate change and to carry out these actions from a depth of 30 metres, where the effect of global change is less”, says the expert.

Assessing restoration with long-term timescales

Traditionally, the success of this marine restoration actions profile of is evaluated based on the short-term survival of the transplanted organisms. “This approach is limited, especially for long-lived species such as coral, which could reach a longevity of 50 to 100 years. Many target species need more time to recover than the monitoring period, which mostly focuses on the first few years after restoration. Similarly, it also does not allow for the assessment of ecosystem-scale changes, such as the recovery of functions and services”, say Linares and Zentner.

The new study is a first step towards working at relevant temporal and ecological scales, carrying out long-term monitoring through community-scale analyses, which allow inferring changes in the functions and services provided by the species present. “More specifically, dominance and functional diversity are indicators that allow us to quantify changes in the functional structure of the coralligenous habitat: in this case, we have been able to detect an increase in the structural complexity and resilience of the restored community”, note the experts.

Tropical systems are the marine habitats where most coral restoration has been carried out, but its long-term success has often not been assessed, which is important given the increasing impact of climate change. In the Mediterranean, the research team has been involved in previous studies on the restoration of corals and gorgonians rescued from fishing nets and transplanted to protected deep sea beds.

Globally, restoration actions in the marine environment are still at an early stage. In particular, the first scientific methodologies are only just being tested, and most are aimed more at mitigating an impact than at restoring an entire ecosystem. At the same time, there is still a significant lack of best practice protocols for these actions.

“For restoration to be efficient, the source of stress that has degraded the system to be restored must be removed. In the case of the marine environment, due to global change, there is practically no corner of the world that is protected from human impacts. Therefore, before restoring, we must consider how to protect the sea effectively”, note the researchers. “On the other hand, — they add — we must manage to increase the scale at which we work, since, due to the impediments of working in the marine environment, many restoration actions (including this study) are carried out on a small local scale, and have a low return at the ecosystem scale”.

The study reveals the high survival of the transplanted red coral colonies after so many years

The red coral colonies that were transplanted a decade ago on the seabed.

The red coral colonies that were transplanted a decade ago on the seabed.

These colonies, seized years ago from illegal fishing, have found a second chance to survive,

These colonies, seized years ago from illegal fishing, have found a second chance to survive,

Credit

MedRecover Research Group

Journal

Science Advances

Method of Research

Experimental study

Subject of Research

Animals

Article Title

Active restoration of a long-lived octocoral drives rapid functional recovery in a temperate reef