A respite for sofas and spaghetti: Trump eases and delays tariffs

Planned tariff hikes on imported furniture are pushed back a year, while punishing tariffs on Italian pasta are scaled down after months of negotiations.

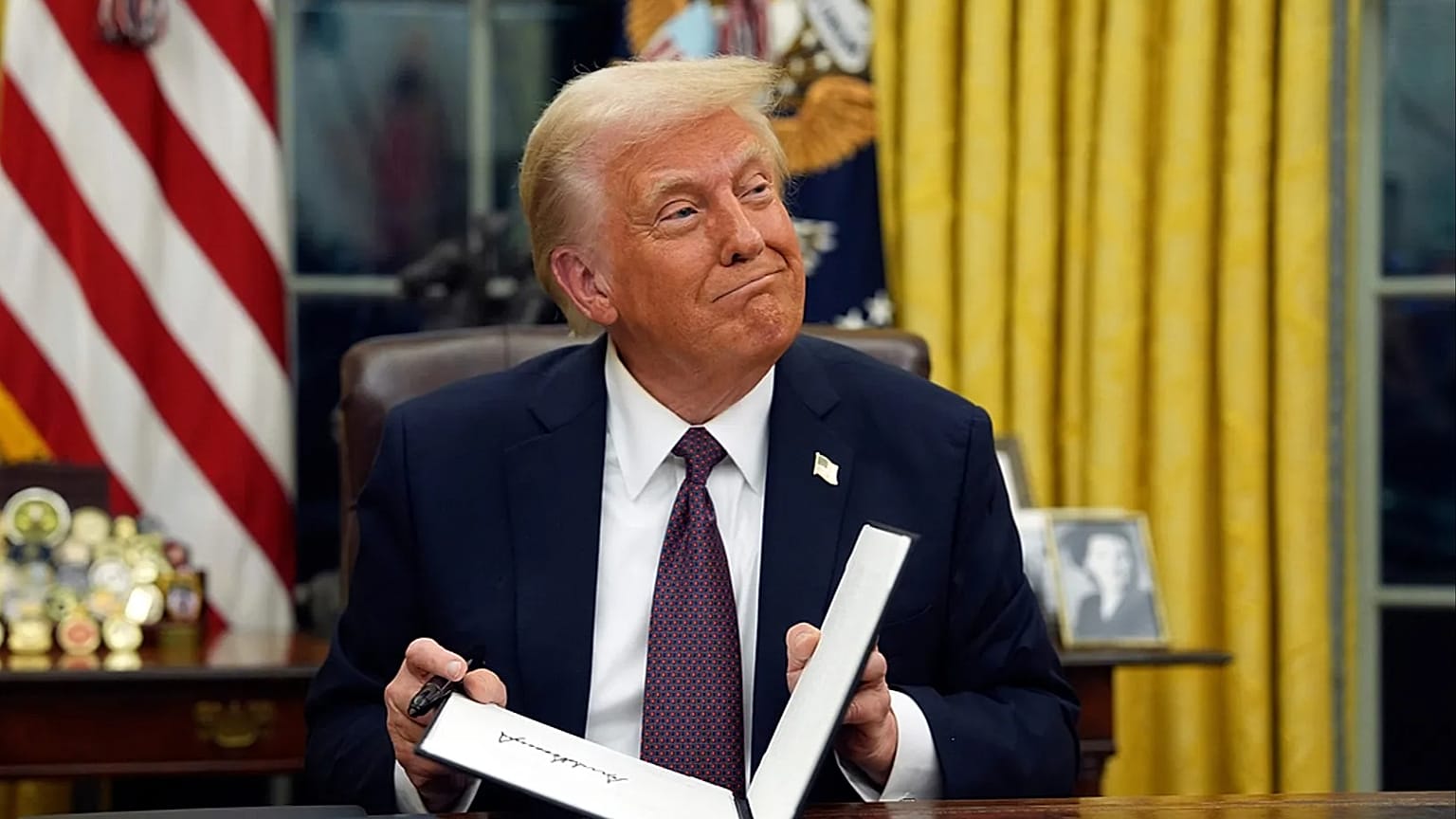

President Donald Trump has eased pressure on two key import sectors — furniture and pasta — by delaying or scaling back steep tariffs shortly before they were due to take effect on 1 January, 2026.

For furniture, Trump has postponed planned tariff increases on certain imported home goods for one year, keeping existing duties in place while allowing further negotiations with trading partners.

On Wednesday Trump signed a proclamation delaying the scheduled increases — originally set to take effect on Thursday — until January 1, 2027.

The order preserves the current 25% tariff on “certain upholstered wooden products,” kitchen cabinets and vanities, rather than allowing it to rise to 30% for upholstered furniture and 50% for kitchen cabinets and vanities as previously directed.

“The United States continues to engage in productive negotiations with trade partners to address trade reciprocity and national security concerns with respect to imports of wood products,” the White House said in a statement announcing the move

The furniture tariffs were imposed in September 2025 under a broader push to reshape US trade relationships and protect domestic industries. In addition to the 25% on furniture and cabinets, the administration also placed a 10% duty on imported softwood timber and lumber late last year.

The higher rates that were set to begin this week would have hit imports from major suppliers like Vietnam and China particularly hard and come amid ongoing concern about rising consumer prices.

Separately, the US Supreme Court is expected to rule on the legality of some broad tariff measures imposed under national security authorities, a decision that could have wider implications for Trump’s trade strategy.

In contrast to the furniture delay the Trump administration has significantly reduced planned anti-dumping duties on Italian pasta, offering relief to several major brands after months of dispute.

The US Department of Commerce had initially proposed very high provisional anti-dumping duties — more than 91% — on certain imports of Italian pasta, on top of an existing 15% general tariff on EU food products.

Following a review and consultations with Italian authorities, the United States lowered those planned tariffs sharply. La Molisana will face a 2.26% duty, Garofalo will face a 13.98% duty and eleven other Italian producers will face 9.09% duties.

“The redefining of these tariff rates is a testament to the US authorities’ recognition of our companies’ effective will to cooperate,” Italy’s foreign ministry said in a statement.

Italy had been working with both the US government and the European Commission since October 2025 to find a solution to the dispute.

The US market remains crucial for Italian pasta producers. Exports of pasta to the United States were estimated at about €671 million in 2024, representing roughly 17% of Italy’s total pasta exports.