To Best Understand Inequality, Think Class, Not Generation

Our age cohorts don’t tell the full story

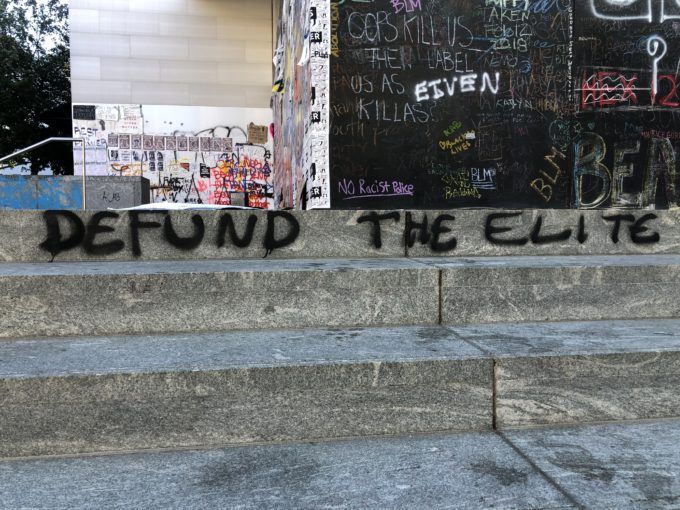

Source: Inequality.org

How much does the generation we belong to define the comfort of the lives we lead? Just about nothing impacts our comfort, suggests a recent spate of major media news analyses, more than our generation.

“Millennials had it bad financially,” as a Washington Post feature put it last month, “but Gen Z may have it worse.”

Demographers typically define millennials as those Americans born between 1980 and 1994. Gen Z covers the cohort that came on the scene between 1995 and 2012.

The tens of millions of Americans in both these generations, goes the standard analysis, enjoy precious little of the good life that has blessed America’s baby boomers, those lucky 60- and 70-year-olds born right after World War II between 1946 and 1964.

The New York Times earlier this year, for instance, interviewed a Michigan millennial who works as a university archivist. She’s still paying off, decades after graduating, her student loans. Three years ago, this millennial bought a 10-year-old used car, a transaction that wiped out most of her savings. Many of her millennial peers, the archivist told the Times, are finally starting to buy homes and raise families, but “a lot of my generation has had to put that all on hold.”

Young people in Gen Z, the available data also make rather clear, are facing even greater economic challenges. Gen Z’ers are paying 31 percent more for housing than millennials, even after taking inflation into account, and 46 percent more for health insurance. Gen Z has become, adds the Washington Post, “the first generation where recent college grads are more likely to be unemployed than the general population.”

Amid that general population, baby boomers stand economically supreme. Boomers, a cohort that makes up a mere 20 percent of the U.S. population, now hold 52 percent of the nation’s net wealth. The baby boom generation, sums up the Economist magazine, may well turn out to be “the luckiest generation in history.”

Analyses like these have been creating the fairly widespread impression that boomers have convincingly “won” what has been a generational war — at the expense of America’s younger generations. But this “generational war” framing more distorts than describes the reality Americans are living. Millions of boomers in the United States today are not doing well economically. Significant numbers of millennials and Gen Z’ers are annually raking in millions.

What’s going on here? We’re not suffering through a generational war. We’re continuing to live through a clash of economic classes.

Baby boomers just happened to have had the good fortune to come along at one of those rare moments in history when the richest among us were not doing so well in that clash of classes. These boomers found themselves born into a postwar America that average people — after years of struggle — had fundamentally transformed.

By the late 1940s, across huge swatches of the United States, most workers carried union cards. The contracts their unions bargained made the country they called home the first industrial nation in the entire world where the majority of workers, after paying for life’s most basic necessities, actually had significant money left over.

Throughout those same mid-century years, meanwhile, America’s rich were facing top-bracket federal income tax rates that hovered around 90 percent.

The tax code of those years did, to be sure, have loopholes that America’s wealthiest could exploit. But these loopholes largely benefited only a narrow sliver of Americans of means, mostly those rich who owed their wealth to fossil fuels. On the first annual Forbes 400 list in 1982, nine of America’s wealthiest top fifteen had Big Oil to thank for their fortunes.

The poorest deep pocket on the initial Forbes top 400 — Apple’s Armas Markkula Jr. — sat on a 1982 fortune worth a mere $91 million, the equivalent of about $296 million today. On the current Forbes 400, America’s poorest mogul holds a fortune worth $6.9 billion, a stash over 23 times larger than the 1982 fortune at the bottom of the Forbes first modern-era top 400.

The business network CNBC has dubbed the wealth gap within the ranks of millennials “the new class war.” The “vast majority” of this generation, notes CNBC’s Robert Frank, is facing draining student debt, low-wage service-jobs, and unaffordable housing. On average, millennials at age 35 have held 30 percent less wealth than baby boomers at that same age. But the richest top 10 percent millennials have averaged 20 percent more wealth than their baby boom top 10 percent counterparts.

Today’s concentration of millennial — and Gen Z — wealth suits the purveyors of luxury watches, wines, and classic automobiles just fine, points out a new Bank of America study of millennial and Gen Z households holding at least $3 million in investable assets. Some 72 percent of deep pockets aged 43 and younger, the study adds, deem themselves “skeptical” about investing mainly in traditional stocks and bonds. By 2030, a Bain & Co. report released earlier this year estimates, affluent millennials will account for 50 to 55 percent of luxury market purchases and Gen Z’ers another 25 to 30 percent.

All this should serve to remind us about a basic simple truth. We can’t change the generation we get born into. We can change how the world we enter distributes income and wealth.

Sam Pizzigati

Sam Pizzigati, an associate fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies, has written widely on income and wealth concentration, with op-eds and articles in publications ranging from the New York Times to Le Monde Diplomatique. He co-edits Inequality.org Among his books: The Rich Don’t Always Win: The Forgotten Triumph over Plutocracy that Created the American Middle Class, 1900-1970 (Seven Stories Press). His latest book: The Case for a Maximum Wage (Polity). A veteran labor movement journalist, Pizzigati spent 20 years directing publishing at America’s largest union, the 3.2 million-member National Education Association.