As the cost of capital goes up, the prospects for fossil fuel projects go down.

Photo by CleanTechnica

By Steve Hanley

There is an interesting email from Bloomberg Green today. It discusses how the cost of capital is going up for fossil fuel companies and down for renewables. The concluding sentence goes like this: “Markets may end up killing off fossil fuels before governments do.” Why is that? Let’s dig into the details behind that rather startling statement.

The Cost Of Capital

I am no economist, so some of you may find my comments naive, quaint, or even flat out wrong. In general, when a business like Exxon wants to go mucking about with the Earth, drilling test holes here and there in search of new oil deposits, it turns to financial markets to borrow the money it needs to finance those quests.

Investors want to be paid back with interest. How much interest is usually determined by how risky the investment is. The higher the risk, the greater the interest. Bloomberg executive editor Tim Quinson writes in today’s email that a decade ago, the cost of capital for for developing oil and gas projects and for renewable projects was pretty much the same — somewhere between 8% and 10%.

Not anymore, he writes. The threshold of projected return that can financially justify a new oil project is now at 20% for long cycle developments, while for renewables it has dropped to somewhere between 3% and 5%. That’s according to Michele Della Vigna, a Goldman Sachs analyst based in London.

“That’s an extraordinary divergence which is leading to an unprecedented shift in capital allocation,” Della Vigna says. “This year will mark the first time in history that renewable power will be the largest area of energy investment.”

Why The Change?

The first question most people will ask is, why the change? Will Hares, an analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence, explains that pressure from ESG investors is the best explanation for the widening difference between dirty and clean. “Oil companies are finding it increasingly difficult to raise financing amid rising ESG and sustainability concerns, while banks are under pressure from their own investors to reduce or eliminate fossil-fuel financing,” he says.

This is resulting in more expensive debt financing (in some cases double-digit coupons), which, when coupled with depressed equity valuations, leaves most oil companies facing higher costs for capital, Hares adds.

The Conversation At COP26

It this a sick joke? Apparently there were more fossil fuel lobbyists in Glasgow last week that the number of climate conference delegates from any one of the world’s nations. If that doesn’t make you want to puke, I don’t know what would. These smarmy, smirking sycophants get paid to sabotage climate talks so the companies they represent can continue to poison the environment with the waste products that come from burning fossil fuels. They should all be hauled before the International Criminal Court and charged with crimes against humanity.

Future Investments In Renewables

In Glasgow last week, Della Vigna estimated about $56 trillion, or roughly $2 trillion a year, will be invested in renewable energy, bio-energy, and other clean energy infrastructure projects between now and 2050. Spending is expected to peak between 2035 and 2040, driven largely by expenditures on power networks, charging networks, building upgrades, and a massive expansion of renewable power sources such as clean hydrogen.

“It’s significant that such a large share of the financial sector has recognized its role in driving the climate crisis and the need to wind down its financed emissions,” Ben Cushing, a campaign manager at the Sierra Club, tells Bloomberg. “But achieving net zero by 2050 and staying within 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming means stopping financing for fossil fuel expansion today. That’s the key test for whether these commitments are aligned with reality.”

Managing The Spread

“Given this backdrop, the spread between oil, gas and coal and renewable energy will continue to diverge as banks change their financing habits,” says Quinson. In other words, while the politicians are all huddled around the free shrimp cocktail table in Glasgow, the financial community is about to do what they will not or cannot.

Banks and investment firms are not elected by anyone and answer only to the almighty dollar. When lending (and insurance coverage) to fossil fuel companies dries up, it’s game over for them. They can lie to Congress, they can pour money into the campaign coffers of crooks like Joe Manchin, they can fund groups like the American Petroleum Institute to their hearts content, but without access to capital that’s affordable, they are done. Finished. Kaput.

Numbers don’t lie and the bottom line is the bottom line no matter what some politician or lobbyist says. The cost of capital is a significant factor when calculating the levelized cost of energy from any source. When that cost goes up, oil, coal, and dirty methane ventures look a whole lot less attractive. There is an excellent chance the financial sector will put fossil fuels out of business long before our political leaders find the courage to act.

Cost of Capital Spikes for Fossil-Fuel Producers

Ten years ago, developing oil and gas projects was about the same as renewable endeavors. Not anymore.

“It's significant that such a large share of the financial sector has recognized its role in driving the climate crisis and the need to wind down its financed emissions,” said Ben Cushing, a campaign manager at the Sierra Club, an environmental pressure group. “But achieving net zero by 2050 and staying within 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming means stopping financing for fossil-fuel expansion today. That’s the key test for whether these commitments are aligned with reality.”

It’s likely that given this backdrop, the spread between oil, gas and coal and renewable energy will continue to diverge as banks change their financing habits. Indeed, markets may end up killing off fossil fuels before governments do.

Sustainable finance in brief

Adam Smith, considered by many to be the “father of modern economics,” is having his signature work updated to allow for the climate crisis. A group of economists are reworking Smith’s “The Wealth of Nations” to reflect the modern challenge of a warming planet. Above, a marker leads to Smith’s grave in Edinburgh, Scotland.

Photographer: Adam Berry

Adam Smith’s “Wealth of Nations” gets an update to accommodate the climate crisis.

Former U.S. Vice President Al Gore warns the world about a multitrillion-dollar “subprime carbon bubble.”

Singapore aims to curb greenwashing by way of stress test technology.

Lazard Chief Executive Officer Ken Jacobs says he seeks to plug the green knowledge gap.

World Bank’s Climate Warehouse is looking to blockchain technology to solve carbon data issues.

Bloomberg Green publishes the ESG-focused newsletter every week, providing unique insights on climate-conscious investing.

Ten years ago, developing oil and gas projects was about the same as renewable endeavors. Not anymore.

By Tim Quinson

BLOOMBERG GREEN

November 9, 2021

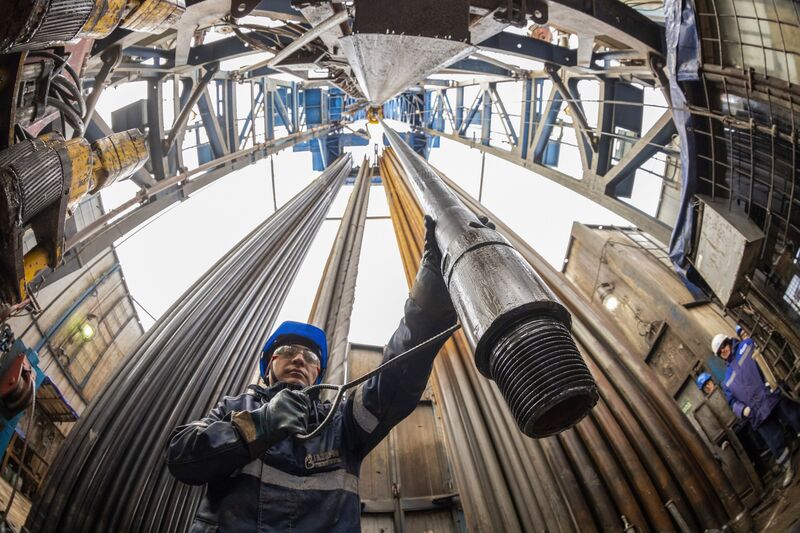

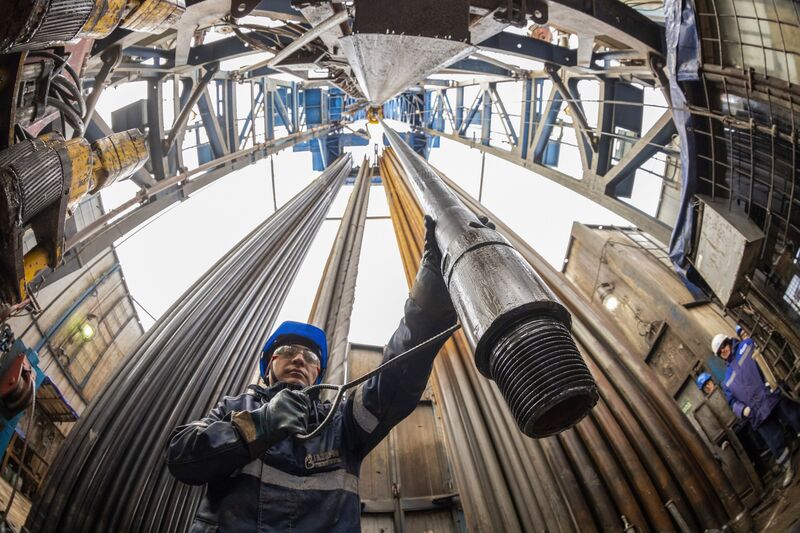

A worker guides a drilling pipe at the Gazprom Chayandinskoye oil, gas and condensate field near Lensk, Russia, on Oct. 13.

November 9, 2021

A worker guides a drilling pipe at the Gazprom Chayandinskoye oil, gas and condensate field near Lensk, Russia, on Oct. 13.

Photographer: Andrey Rudakov/Bloomberg

Ten years ago, the “cost of capital” for developing oil and gas as compared to renewable projects was pretty much the same, falling consistently between 8% and 10%. But not anymore.

The threshold of projected return that can financially justify a new oil project is now at 20% for long-cycle developments, while for renewables it’s dropped to somewhere between 3% and 5%, according to Michele Della Vigna, a London-based analyst at Goldman Sachs Group Inc.

“That's an extraordinary divergence, which is leading to an unprecedented shift in capital allocation,” Della Vigna said. “This year will mark the first time in history that renewable power will be the largest area of energy investment.”

Cost of Capital: Fossil Fuels vs. Renewable Energy

Source: Goldman Sachs

Note: Figures for 2020 are estimates.More from

Will Hares, an analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence, said pressure from ESG investors is the best explanation for the widening difference between dirty and clean.

“Oil companies are finding it increasingly difficult to raise financing amid rising ESG and sustainability concerns, while banks are under pressure from their own investors to reduce or eliminate fossil-fuel financing,” Hares said.

This is resulting in more expensive debt financing (in some cases double-digit coupons), which, when coupled with depressed equity valuations, leaves most oil companies facing higher costs for capital, Hares said

Ten years ago, the “cost of capital” for developing oil and gas as compared to renewable projects was pretty much the same, falling consistently between 8% and 10%. But not anymore.

The threshold of projected return that can financially justify a new oil project is now at 20% for long-cycle developments, while for renewables it’s dropped to somewhere between 3% and 5%, according to Michele Della Vigna, a London-based analyst at Goldman Sachs Group Inc.

“That's an extraordinary divergence, which is leading to an unprecedented shift in capital allocation,” Della Vigna said. “This year will mark the first time in history that renewable power will be the largest area of energy investment.”

Cost of Capital: Fossil Fuels vs. Renewable Energy

Source: Goldman Sachs

Note: Figures for 2020 are estimates.More from

Will Hares, an analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence, said pressure from ESG investors is the best explanation for the widening difference between dirty and clean.

“Oil companies are finding it increasingly difficult to raise financing amid rising ESG and sustainability concerns, while banks are under pressure from their own investors to reduce or eliminate fossil-fuel financing,” Hares said.

This is resulting in more expensive debt financing (in some cases double-digit coupons), which, when coupled with depressed equity valuations, leaves most oil companies facing higher costs for capital, Hares said

.

Mark Carney at COP26 in Glasgow, Scotland

Photographer: Stefan Rousseau/PA Images/Getty Images

Climate finance has been a hot topic at the COP26 meetings in Glasgow, Scotland. Government leaders from less-developed nations have at times expressed fury that rich countries repeatedly break promises to mobilize funds to help them decarbonize and adapt to a warming planet.

More such pledges were made last week—only this time they came from the financial industry.

Mark Carney, the former central banker turned climate envoy, said more than 450 financial firms representing $130 trillion of assets have pledged to bring their lending and investing activities in line with the goals of the 2015 Paris agreement. The announcement, however, didn’t mollify skeptics who are quick to point out that details on how the industry would actually meet this target were lacking—a hallmark of the greenwashing scourge.

Goldman Sachs estimates that about $56 trillion, or $1.5 trillion to $2 trillion a year, will be invested in renewable energy, bioenergy and other clean-energy infrastructure projects between now and 2050. Spending is expected to peak between 2035 and 2040, driven largely by expenditures on power networks, charging networks, building upgrades and a massive expansion of renewable power sources such as clean hydrogen, Della Vigna said.

Mark Carney at COP26 in Glasgow, Scotland

Photographer: Stefan Rousseau/PA Images/Getty Images

Climate finance has been a hot topic at the COP26 meetings in Glasgow, Scotland. Government leaders from less-developed nations have at times expressed fury that rich countries repeatedly break promises to mobilize funds to help them decarbonize and adapt to a warming planet.

More such pledges were made last week—only this time they came from the financial industry.

Mark Carney, the former central banker turned climate envoy, said more than 450 financial firms representing $130 trillion of assets have pledged to bring their lending and investing activities in line with the goals of the 2015 Paris agreement. The announcement, however, didn’t mollify skeptics who are quick to point out that details on how the industry would actually meet this target were lacking—a hallmark of the greenwashing scourge.

Goldman Sachs estimates that about $56 trillion, or $1.5 trillion to $2 trillion a year, will be invested in renewable energy, bioenergy and other clean-energy infrastructure projects between now and 2050. Spending is expected to peak between 2035 and 2040, driven largely by expenditures on power networks, charging networks, building upgrades and a massive expansion of renewable power sources such as clean hydrogen, Della Vigna said.

“It's significant that such a large share of the financial sector has recognized its role in driving the climate crisis and the need to wind down its financed emissions,” said Ben Cushing, a campaign manager at the Sierra Club, an environmental pressure group. “But achieving net zero by 2050 and staying within 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming means stopping financing for fossil-fuel expansion today. That’s the key test for whether these commitments are aligned with reality.”

It’s likely that given this backdrop, the spread between oil, gas and coal and renewable energy will continue to diverge as banks change their financing habits. Indeed, markets may end up killing off fossil fuels before governments do.

Sustainable finance in brief

Adam Smith, considered by many to be the “father of modern economics,” is having his signature work updated to allow for the climate crisis. A group of economists are reworking Smith’s “The Wealth of Nations” to reflect the modern challenge of a warming planet. Above, a marker leads to Smith’s grave in Edinburgh, Scotland.

Photographer: Adam Berry

Adam Smith’s “Wealth of Nations” gets an update to accommodate the climate crisis.

Former U.S. Vice President Al Gore warns the world about a multitrillion-dollar “subprime carbon bubble.”

Singapore aims to curb greenwashing by way of stress test technology.

Lazard Chief Executive Officer Ken Jacobs says he seeks to plug the green knowledge gap.

World Bank’s Climate Warehouse is looking to blockchain technology to solve carbon data issues.

Bloomberg Green publishes the ESG-focused newsletter every week, providing unique insights on climate-conscious investing.

No comments:

Post a Comment