Peter Singer looks a very tired man. It’s not so much the early morning start of the interview, but the weeks of media scrutiny, misrepresentation and criticism, which seem to have taken their toll.

Singer came to England to talk about "A Darwinian Left", but no sooner had he stepped off the plane than the Daily Express was reviving the old controversy over Singer’s view that in certain circumstances, it may be better to end the life of a very severely handicapped baby in a humane way, rather than use all modern medicine can do to let it live a painful and often brief life. Singer tried to defend himself on Radio Four’s Today programme, but in such a brief news item, his calm reasoning was always likely to have less impact than the emotive pleas of his opponent.

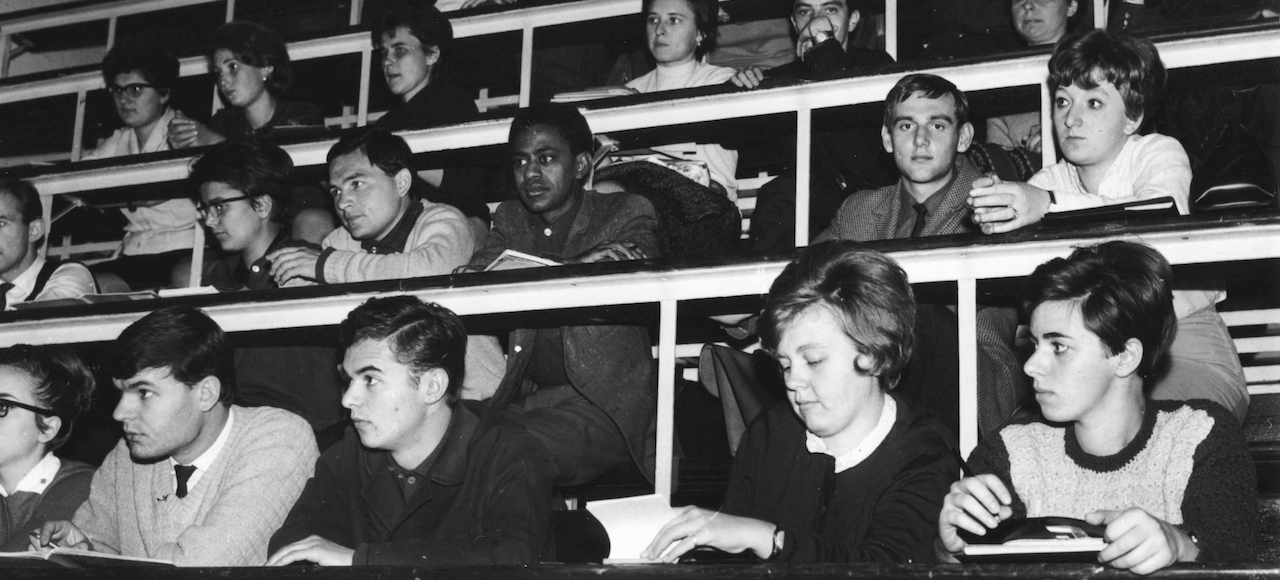

So once again, what Singer really wanted to say was overshadowed by his reputation. Which is a pity, because in his LSE lecture, A Darwinian Left?, which formed the centrepiece of his visit, Singer challenges a rather different taboo: the exclusion from left-wing thought of the ideas of Charles Darwin.

Singer argues that the left’s utopianism has failed to take account of human nature, because it has denied there is such a thing as a human nature. For Marx, it is the "ensemble of social relations" which makes us the people we are, and so, as Singer points out, "It follows from this belief that if you can change the ‘ensemble of social relations’, you can totally change human nature."

The corruption and authoritarianism of so-called Marxist and communist states in this century is testament to the naïveté of this view. As the anarchist Bakunin said, once even workers are given absolute power, "they represent not the people but themselves … Those who doubt this know nothing at all about human nature."

But what then is this human nature? Singer believes the answer comes from Darwin. Human nature is an evolved human nature. To understand why we are the way we are and the origins of ethics, we have to understand how we have evolved not just physically, but mentally. Evolutionary psychology, as it is known, is the intellectual growth industry of the last decade of the millennium, though it is not without its detractors.

If the left takes account of evolutionary psychology, Singer argues, it will be better able to harness that understanding of human nature to implement policies which have a better chance of success. In doing so, two evolutionary fallacies have to be cleared up. First of all, we have evolved not to be ruthless proto-capitalists, but to "enter into mutually beneficial forms of co-operation." It is the evolutionary psychologist’s work in explaining how ‘survival of the fittest’ translates into co-operative behaviour which has been, arguably, its greatest success. Secondly, there is the "is/ought" gap. To say a certain type of behaviour has evolved is not to say it is morally right. To accept a need to understand how our minds evolved is not to endorse every human trait with an evolutionary origin.

When I spoke to Peter Singer, I wanted to get clearer about what he thinks Darwinism can do to help us understand ethics. Singer is a preference utilitarian, which means he thinks the morally right action is that which has the consequences of satisfying the preferences of the greatest number of people. Singer seems now to be saying that the importance of Darwinism is that if we take it into account, we will be better at producing the greatest utility - the satisfaction of people’s preferences.

"That’s my philosophical goal," acknowledges Singer. "I was speaking more broadly for anyone who shares a whole range of values. You don’t have to be a preference utilitarian. But I think it would be true generally that anyone who has views about how society should end up will have a better chance to achieve that if they understand the Darwinian framework of human nature."

Singer also argues that Darwinism has a destructive effect, in that if you accept it, certain other positions are fatally undermined. For example, the idea that God gave Adam, and by proxy, us, dominion over the animal kingdom is a view "thoroughly refuted by the theory of evolution."

I was unsure that those victories are always so straightforward. For example, there are, presumably, many Christians who don’t buy the Adam and Eve creation myth as literal truth. Nevertheless, can’t they live with Darwinism and have their ethics?

"I don’t think Darwinism is incompatible with any Christian ethic," Singer is happy to allow, "except a really fundamentalist one that takes Genesis literally. And it’s not even incompatible strictly with the divine command theory, it just means the divine command theory is based on all sorts of hypotheses which you don’t need because you’ve got other explanations."

So how is the divine command theory undermined by evolution? Couldn’t the Christian, for example, say, yes, evolution is how man came to be, but given there is an is/ought gap, can’t the ethical commands come from on high, as it were?

"Entirely possible. I was just saying that a lot of the impetus for a divine command theory comes from the question ‘where could ethics come from?’. It’s something totally different, out of this world, so therefore you have to assume we’re talking about the will of God or something. Once you have a Darwinian understanding of how ethics can emerge, you absolutely don’t have to assume that, but it’s still possible to assume it. It’s really the ‘I have no need of the hypothesis’ rather than ‘that hypothesis is hereby refuted’."

The question of how far evolution can help us understand the origin of ethics is perhaps the most contentious part of evolutionary psychologists’ claims in general and Singer’s thesis in particular. Singer believes Darwinian theory gives us an understanding of the origin of ethics, because, for example, it gives an evolutionary explanation of how reciprocity came to be. Put crudely, if you model the survival prospects for different kinds of creatures with different ways of interacting with others - from serial exploiters to serial co-operators and every shade in between - it turns out that the creatures who thrive in the long run are those that adopt a strategy called ‘tit for tat’. This means that they always seek to co-operate with others, but withdraw that co-operation as soon as they are taken advantage of. Because this is the attitude which increases the survival value of a species, it would seem to follow that humans have evolved an in-built tendency to co-operation, along with a tendency to withdraw that co-operation if exploited. Hence, it is argued, and essential feature of ethics - reciprocity - is explained by evolution.

But, I put it to Singer, does the is/ought gap reappear in a historical version if you follow that theory? When we give an evolutionary explanation of how reciprocity came to be, so far we’re only describing evolved behaviour, but it’s quite clear that what you think ethics is now goes beyond a mere description of our evolved behaviour. So how, historically or logically, is that gap bridged?

"It’s not bridged historically at all. Of any culture and people you can describe their ethic, but that remains entirely on the level of description. ‘The Inuit people do this and this and this, the British people do that and that and that’. You can describe that ethic but you don’t get from the answer to ‘what ought I to do?’ So the gap is a logical one and it just arises from the fact that when we seek to answer the question, ‘What ought I to do?’ we’re asking for a prescription, we’re not asking for a description. Any description of existing morals in our culture or the origins of morals is not going to enable us to deduce what ought we to do."

But, I insist, doesn’t evolution then merely explain the descriptive part of how certain behaviours came to be? It doesn’t really explain our ethics, it explains social codes, rules of social conduct. If ethics is a prescriptive field rather than a descriptive one, how does evolutionary explanation of how merely described behaviour comes to be explain how ethics came to be?

"I think in a way that’s so obvious that it doesn’t need any explanation," retorts Singer. "That’s just that we have the capacity to make choices and that we make judgements which are prescriptive: first person, second person or third person judgements. So, in a way, that is not what I’m trying to explain the origins of, although you can see how if you add it to the kinds of accounts I’ve given, we have language and we are a social animals you can see why we end up talking about these things and discussing them. It’s not something that I talked about. We know that we do that, and that’s a process you would expect beings, once they had a certain degree of language, faced with these choices, to do."

The question is important, because some prominent workers in the area of decision-theory and evolution argue that evolution explains how it comes to be that we have social rules and that in fact understanding these origins shows us that there’s no extra moral dimension to these things. They are merely evolved and we deceive ourselves if we think there is an ethical dimension.

I tried to probe this apparent gap between evolution and ethics by considering two of Singer’s examples of how our ethics must account for our evolved human nature. If we take into account the fact that we feel more protective towards our own offspring than towards children in general, it’s a good rule that parents should take care of their children because there’s a greater chance it will increase the general happiness. On the other hand, the double standard towards female and male sexual behaviour, even though it may have an evolutionary explanation, is something that should not be tolerated. I put it to Singer that, it follows that the moral judgements that we’re going to make are going to be of the sort, ‘If the evolved behaviour is going to lead to the morally desirable result follow it and if the evolved behaviour does not lead to the morally desirable result, don’t follow it’. So isn’t the observation of what has evolved going to drop out of the equation? It’s not going to feed at all directly into what our moral rules are going to be.

Singer’s answer reveals more precisely the limited, but important role, he believes Darwinian explanations play in our ethics. "I think the Darwinian is going to alert us to what rules are going to work and what rules are going to meet a lot of resistance and I think we have to bear that in mind. But always there’s a trade off between how important the values are to us and the strength of the evolved tendency in our natures."

Given Singer’s willingness to challenge established views, I was a little surprised that he still talks in terms of the left and right, particularly as it seems his conception of the left is a long way from any traditional view. Singer characterises the left as being concerned with eliminating the sufferings of others and of the oppressed. A lot of people on the left would consider that quite a diluted view of the left, which is generally thought to have something to do with common ownership. I wondered if it was useful to maintain the label ‘the left’.

"The label’s kind of there to stay," replies Singer. "It’s been there so long. We’re not about to get rid of it. You would have to be rather far on the left now to think that a lot of common ownership is a good idea, beyond some major utilities. I wouldn’t say the left ought to be committed to common ownership. Common Ownership is possibly a means to achieving the goals of the left. That debate should continue. But I wouldn’t say it was a prerequisite for being part of the left."

But is Singer’s view really leftist at all? Take what he says about tit-for tat, for example. He argues that tit-for-tat would appeal to people on the left because it is a ‘nice’ strategy, but presumably a lot of people who wouldn’t identify themselves as left-wing would be keen on adopting what he calls nice strategies. And similarly a number of people on the left might be against the nicer strategies - the more revolutionary left wing, for example. So I’m left wondering if there really is a significant distinction to be made between the left and other political stances that are committed to the reduction of inequality.

But it’s quite clear that Singer, though keen to identify himself as being on the left, isn’t as interested this particular issue as I am. He simply replies, "I think there’s a lot less to the distinction [left/right] than there was, undoubtedly."

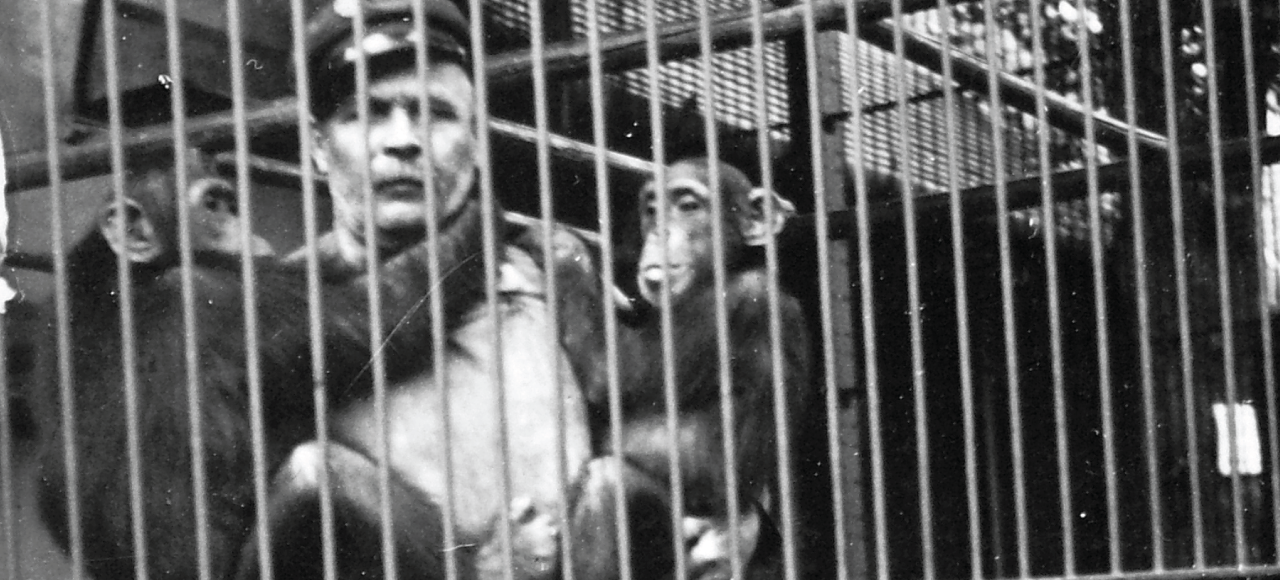

Singer’s interest in Darwin pre-dates the current revival in evolutionary explanations, and goes back to his earlier work in animal liberation.

"It was there in the background. It wasn’t central to it but I did talk about it a bit in Animal Liberation. I certainly was interested in it before Wilson’s Sociobiology came out, but my interest in it as an aid to understanding what ethics is really does date from Sociobiology because I then addressed that in the Expanding Circle, which was published in 1982, and that was explicitly a response to Wilson."

What, I wondered, explains the current explosion of interest in Darwin, particularly in philosophy and psychology?

"Well, Darwin’s been around for such a long period of time but understanding Darwinian accounts of human affairs has not been about for such a long time. It’s been neglected after Darwin himself. And then there was this great taboo against applying Darwinian hypotheses to human social behaviour until Wilson’s Sociobiology in 1975 and that was greeted with a huge amount of hostility, which is evidence of the taboo. Even then a lot of people shuddered because they saw it as something that was associated with nasty, right-wing biological determinism, which is not really true. So it’s only more recently than 1975 that the taboo has broken down and people have started to accept that there are interesting and important insights into human affairs that come from applying Darwinian thinking to human social conduct."

Singer may feel that his new take on Darwin ought to have been the main focus of his visit to London. But aside from Singer the academic philosopher, there is also Singer the campaigner and polemicist. If the media have focused on other things, it is at least partly due to Singer’s own outspokenness about issues that matter to him.

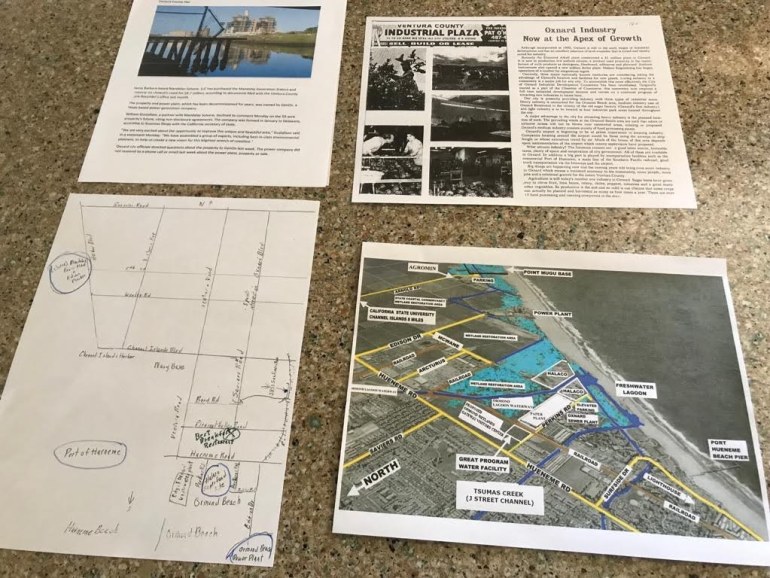

One of the first controversies to blow up in the press during Singer’s visit was his withdrawal of a lecture he was due to give at the King’s Centre for Philosophy, because of its sponsorship by Shell UK, and his very public letter to the Guardian explaining why.

Singer’s reason for pulling out is that, "I did not really want to appear on a programme that says ‘supported by Shell’ and is seen as therefore promoting the idea that Shell is a good corporate citizen. It’s not that I’m against taking corporate money under any circumstances. I think there are some circumstances in which I would take it, but I think that you always have to be careful about taking corporate money. At present Shell’s record, particularly in Nigeria, is really lamentable. I think that you can see a connection between the money that is going here [to the King’s Centre] and the profits made out of the extraction of oil in Nigeria, with all of the consequences that has for the Ogoni people, both in terms of environmental damage to their land, the way in which Shell revenues support the Nigerian dictatorship, which is one of the most oppressive around. So I just didn’t want to be part of that."

Interestingly, at one recent Environmental Ethics conference, at which the Shell issue in particular was in the forefront of people’s minds, a lot of the people who ran consequentialist arguments at the conference actually came out in favour of taking the money because they felt that the benefits of having the conference supported would outweigh the very marginal benefits that Shell would receive for having its logo in the corner of the posters. People said thinks like "It’s better this money is spent on a conference in environmental ethics, which should be discussed, than the money should go to a big billboard poster for Shell or something." What does Singer, as a consequentialist, make of this argument?

"The consequentialist could go both ways, I don’t deny that. I don’t think it’s all that important to have another environmental ethics conference frankly - there are plenty of environmental ethics conferences and discussions about environmental ethics around. There’s certainly an argument about what else would happen to the money. But I think that in fact it’s clear that as far as my gesture of refusing to take Shell’s sponsorship is concerned - and it was a gesture, there’s no doubt about it - it’s had worthwhile consequences. What it’s meant is that there’s one lecture in my London programme that did not go ahead as sponsored, but in fact that was made up for by the fact that I gave a lecture organised at King’s College by some students who were opposed to Shell’s sponsorship. So people at King’s still got to hear me give a lecture, if that’s what the were interested in. Because I refused and because I wrote a letter to The Guardian about my refusing to do so, there was a whole lot more discussion of the issue, so people have again become more aware that there is a real issue about corporate sponsorship and the question about Shell in particular has got aired. So, it seems to me that’s clearly been a good thing. In other words, it’s clear that I made the right decision on consequentialist grounds.

"But I think it’s important that people enter some discussion, that it’s not just a silent gesture that I didn’t give a lecture and no one ever heard about why I didn’t."

Singer is always very open in showing the full implications, consequences and ramifications of his viewpoint, which doesn’t always make him popular. As a consequentialist, how does he feel about the argument that the best way to bring about a better society from a utilitarian point of view is not to advance complex utilitarian arguments but to appeal to more simple concepts?

"I think people are in different positions and different roles. For a political heavyweight involved in strategies for a political party to achieve office, it probably wouldn’t be possible to be quite so open. But I think philosophers can have a role in clarifying people’s thinking, with broader aims than simply saying ‘I want the political party with these view to get into office and do this and that’."

As an animal rights campaigner, I suggest, his roles perhaps are more mixed and I asked Singer whether he felt that being so open, and talking about the implications of his views on animals for mentally handicapped children, has had the effect of blunting his points on animal liberation, because people are inevitably not going to focus on his positive points about animals, they focus on the perceived negative implications for the sanctity of life.

"Maybe that’s true. It’s become a larger focus in recent years. I’m not quite sure why, but I think that what you’d have to say there was that if you take the line that that was a mistake to write Should the Baby Live? back in 1985. It’s done now and I think the book’s done some good in alerting people to the nature of that particular problem and making parents of the disabled able to discuss it more openly. I’m not going to deny that the conclusions still seem to be sound ones.

"I think you could say that politically it’s been a mistake to accept invitations to debate it. What’s happened in Britain over the last couple of weeks is that there was a rather silly article in the Daily Express that raised this issue, which probably should have been ignored, and I was called by the BBC for the Today programme and a lot of people heard that, so maybe I would be more prudent to tell the BBC that I didn’t really want to discuss that anymore and that wasn’t what I was coming here to discuss this time.

"It’s very hard because on the other hand some of the discussions were quite useful and it wasn’t all silly stuff as the one on the Today programme I think was. So you have to say, well, it gets more attention and more read about my views, maybe some of them will think, ‘Well, this is not so silly and bad, maybe I should look at some of his books’, and maybe more people will get involved in it. It’s very hard to say, I think."

Singer is always going to be a controversial thinker because of his willingness to confront political and ethical issues without being constrained by current orthodoxy. His application of Darwin to left-wing thought is certainly not going to make him popular with the right, but it is also likely to lose him some friends on the left, just as his measured contribution to the issue of animal rights challenges society’s attitudes while not going far enough to satisfy many activists.

Singer returned to his native Australia leaving behind a big question and a tentative answer. Can the scientific theories of Charles Darwin really contribute to our philosophical understanding of ethics? Singer has tried to show how it can, but this is a debate which clearly has a lot further to run.

Julian Baggini's latest book, Freedom Regained: The Possibility of Free Will, is published by Granta in the UK and by Chicago University Press in North America.

https://www.philosophersmag.com/

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/70780340/WAM518.0.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22528977/chickencow.jpeg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23407002/WAM7426.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23406997/WAM9893.jpg)