Pakistan attempts to prosecute Ahmadi US citizens for digital blasphemy

In 2016, Pakistan enacted digital regulations that allow authorities to block online content in the 'interest of the glory of Islam.'

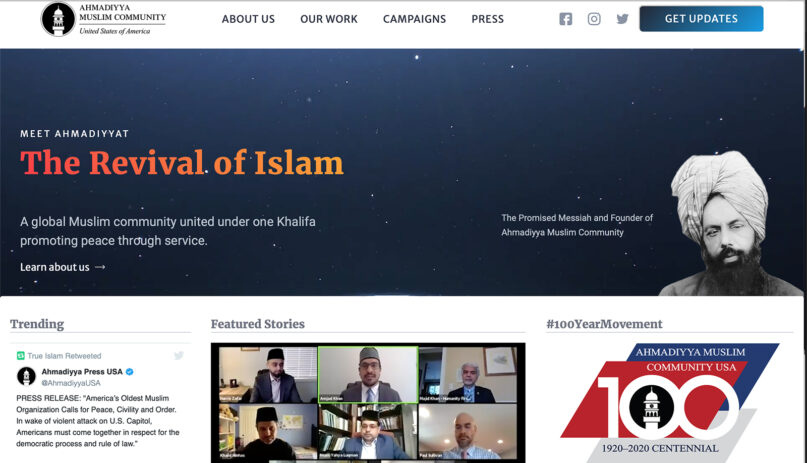

(RNS) — Pakistani authorities have asked leaders of the American Ahmadiyya Muslim community to take down its official website, claiming that the U.S.-based site violates Pakistan’s strict blasphemy laws and new cybercrime regulations.

The Pakistan Telecommunication Authority said in a legal notice issued on Dec. 24 to the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community USA’s spokesmen, Amjad Mahmood Khan and Harris Zafar, that failure to remove the website TrueIslam.com would result in fines of up to $3.14 million or criminal sanctions, including possible 10-year-prison sentences.

“This is a new frontier in persecution of Ahmadi Muslims in the digital space,” said Khan, a lawyer in Los Angeles who has testified before Congress about blasphemy and religious freedom. “Pakistan wants to impose its abominable blasphemy laws on the whole world by targeting U.S. citizens and U.S. websites.”

Brad Adams, who heads Human Rights Watch’s Asia Division, said “censoring Ahmadis and using blasphemy laws to airbrush them from Pakistani society” is part of the “widespread and rampant discrimination and social exclusion” Ahmadis face in Pakistan.

In Pakistan, home to about 4 million Ahmadis, the constitution and penal code declare members of the Ahmadiyya sect non-Muslims and impose harsh penalties — including death — for those who call themselves Muslims or publicly engage in religious activities. Ahmadis accepts the sect’s 19th-century founder, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, as the messiah and as a subordinate prophet to the Prophet Muhammad, a belief many Muslims consider blasphemous.

“This is a malicious attempt to chill free speech and expression by a Muslim American website,” attorney Brett Williamson of O’Melveny & Myers, which is representing TrueIslam.com pro bono, wrote in a letter to PTA on Monday (Jan. 11).

He described the takedown notice as “legally infirm, but also patently absurd in its reach.”

The website is registered and hosted in the U.S. and is aimed at an American audience. Zafar and Khan are both U.S. citizens and the threat of extradition is virtually nil, but both have relatives in Pakistan and say penalties would make it impossible to travel there.

Law professor Arturo Carrillo, who directs George Washington University Law School’s Global Internet Freedom Project, said this case shows that the Pakistan government is now using its controversial cybercrime laws in an effort “to repress online expression and content emanating from outside the country’s borders because the government has deemed it to be undesirable and unlawful.”

Ahmadiyya Muslim Community USA spokesmen Amjad Mahmood Khan, left, and Harris Zafar. Photos via Twitter

PTA officials did not respond to requests for comment.

In 2016, Pakistan enacted digital regulations that allowed authorities to block online content in the “interest of the glory of Islam.” Last year, the government passed blanket censorship laws that would allow authorities to order tech companies to remove digital pornography, blasphemy and anti-state content, drawing ire from Google, Facebook, Twitter and other platforms.

But human rights experts say the takedown notices also come amid increased targeting of Ahmadis’ online religious expression.

One day after issuing the takedown notice to TrueIslam.com, PTA also sent notices to Google and Wikipedia, threatening penalties and prosecution if the platforms failed to remove “sacrilegious content” associated with the Ahmadi sect’s beliefs.

PTA said it was responding to complaints regarding an “unauthentic” Ahmadi translation of the Quran on the Google Play Store; “misleading” search results that returned the Ahmadi leader Mirza Masroor Ahmad’s name when the term “Khalifa (caliph) of Islam” was searched; and “deceitful” Wikipedia articles that suggested that the Ahmadi caliph is Muslim.

Officials also demanded that all internet service providers serving Pakistan block content from Ahmadi websites, including TrueIslam.com, the English-language magazine Al Hakam and the international satellite TV network MTA.

Five of Pakistan’s top Ahmadi leaders have also had cases filed against them in recent weeks over religious activity on WhatsApp, Khan told Religion News Service.

Earlier in December, Khan told a hearing of the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom that extremists in Pakistan were intent on using the country’s cyber crime statutes to initiate blasphemy cases against Ahmadis.

But this latest action, Khan told Religion News Service, is “a very slippery slope in terms of what this could mean for other minorities. We’re the canaries in the coal mine. This would mean any potential website or digital content that is quote-unquote blasphemous can be the subject of criminal prosecution.”

USCIRF Commissioner Johnnie Moore described the takedown notices as “recklessly brazen” and said he expected fierce bipartisan condemnation from both the Trump and Biden administrations.

“Surely, the Pakistani government doesn’t intend on threatening American citizens within the United States?” Moore asked. “Surely, Prime Minister Imran Khan doesn’t want this controversy, now?”

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/FYZCGKX6MCX2447G6Z3IAMZNYU.jpg)

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/SSLGGOLEBN2I4JAURSNANQCN3U.jpg)

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/MZUNE55XJLIGXVLZQCDSZVZUYM.jpg)

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/RL4FLSIFO3UIX6FRS4FIZQ7XKI.jpg)