Dolphins and other mammals capable of learning sounds may emit calls at higher pitches, a new study suggests.

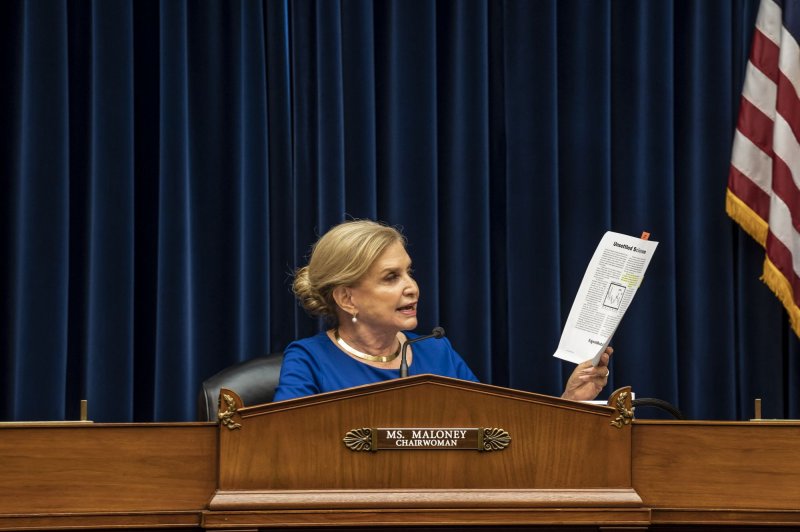

File photo by Neirfy/Shutterstock

Nov. 16 (UPI) -- Animals capable of learning sounds tend to produce calls at higher pitches, a study published Tuesday by the journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences found.

Understanding these tendencies can help scientists better identify mammals capable of what is known as vocal learning, the researchers said.

It also could assist efforts to interpret the meaning of the sounds animals make, according to the researchers.

In their analysis of the vocal tendencies among several species, they noted that the manatee, or sea cow, produces calls that are higher than would be expected given its size, they said.

RELATED Species that use sound to 'fake' body size are usually skilled vocal learners

This may mean that the manatee, which to date has not been considered an animal capable of vocal learning, may have hidden vocal talents, the researchers said.

Similarly, non-vocalists who sound lower than expected, such as the Juan Fernandez fur seal, may turn out to have evolved specific anatomical adaptations to avoid predators, according to the researchers.

"We do not claim that all vocal learner species sound higher than expected for their body size," co-author Maxime Garcia said in a press release.

However, "there is a general trend, and this may help us to better characterize vocal communication in mammals," said Garcia, a post-doctoral researcher in evolutionary biology at the University of Zurich in Switzerland.

Some animals -- red deer, for example -- sound "bigger" than they really are, meaning they produce calls that are lower than would be expected based on their body size, according to Garcia and his colleagues.

Biologists think that this "faking" of body size might be a strategy to impress the opposite sex for mating purposes or to fool and intimidate potential predators.

In a study published last year, Garcia and colleague Andrea Ravignani, a research group leader in comparative bioacoustics at the Max Planck Institute Psycholinguistics in Germany, observed that animals who can fake their body size using their calls also tend to be good at learning sounds.

For this study, they expanded their earlier analyses of a wide range of mammals, including various breeds of bats, dolphins, porpoises, seals and whales.

Contrary to expectations, most vocal learners, such as dolphins, whales and seals, sounded higher than would be expected based on their body size, not lower, the researchers said.

This suggests animals that are good vocal learners usually emit sounds at higher pitches, they said.

Vocal learners who sounded lower than expected often had anatomical adaptations that could explain the lowered voice, such as a longer nose, according to the researchers.

"There might be an alternative evolutionary scenario in vocal learners, where selective pressures favor individuals that can change their tone of voice from low to high," Ravignani said in a press release.

Nov. 16 (UPI) -- Animals capable of learning sounds tend to produce calls at higher pitches, a study published Tuesday by the journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences found.

Understanding these tendencies can help scientists better identify mammals capable of what is known as vocal learning, the researchers said.

It also could assist efforts to interpret the meaning of the sounds animals make, according to the researchers.

In their analysis of the vocal tendencies among several species, they noted that the manatee, or sea cow, produces calls that are higher than would be expected given its size, they said.

RELATED Species that use sound to 'fake' body size are usually skilled vocal learners

This may mean that the manatee, which to date has not been considered an animal capable of vocal learning, may have hidden vocal talents, the researchers said.

Similarly, non-vocalists who sound lower than expected, such as the Juan Fernandez fur seal, may turn out to have evolved specific anatomical adaptations to avoid predators, according to the researchers.

"We do not claim that all vocal learner species sound higher than expected for their body size," co-author Maxime Garcia said in a press release.

However, "there is a general trend, and this may help us to better characterize vocal communication in mammals," said Garcia, a post-doctoral researcher in evolutionary biology at the University of Zurich in Switzerland.

Some animals -- red deer, for example -- sound "bigger" than they really are, meaning they produce calls that are lower than would be expected based on their body size, according to Garcia and his colleagues.

Biologists think that this "faking" of body size might be a strategy to impress the opposite sex for mating purposes or to fool and intimidate potential predators.

In a study published last year, Garcia and colleague Andrea Ravignani, a research group leader in comparative bioacoustics at the Max Planck Institute Psycholinguistics in Germany, observed that animals who can fake their body size using their calls also tend to be good at learning sounds.

For this study, they expanded their earlier analyses of a wide range of mammals, including various breeds of bats, dolphins, porpoises, seals and whales.

Contrary to expectations, most vocal learners, such as dolphins, whales and seals, sounded higher than would be expected based on their body size, not lower, the researchers said.

This suggests animals that are good vocal learners usually emit sounds at higher pitches, they said.

Vocal learners who sounded lower than expected often had anatomical adaptations that could explain the lowered voice, such as a longer nose, according to the researchers.

"There might be an alternative evolutionary scenario in vocal learners, where selective pressures favor individuals that can change their tone of voice from low to high," Ravignani said in a press release.

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/VOJHW27TGZHF7MVIV4CBDMQ7JY.jpg)