Andrew Gomes,

The Honolulu Star-Advertiser

Sun, April 21, 2024

Apr. 21—A state and county objective to produce temporary new homes for Maui wildfire survivors is being hampered by the federal government.

A state and county objective to produce temporary new homes for Maui wildfire survivors is being hampered by the federal government.

Gov. Josh Green and other local government leaders early this year asked the Federal Emergency Management Agency to build 1, 000 homes as part of a multilevel government effort to relocate evacuees of the Aug. 8 Lahaina disaster, including many who have been living in hotel rooms for nearly nine months.

But FEMA has pushed back on the request, only committing to build 169 modular homes in Lahaina under a contract expected to be awarded May 24.

So a goal shortfall of 831 homes exists, despite extra lobbying by Green, Maui County Mayor Richard Bissen and members of Hawaii's congressional delegation.

The 169 homes also represent a 331-home shortfall from 500 expected FEMA-built homes described in a memorandum of understanding signed by state, county and FEMA officials in January as part of a "Maui Interim Housing Plan " that aims to provide 3, 000 homes for survivors.

"Our collective goal is to move all individuals and families who are in short-term hotels into long-term stable housing by July 1, 2024, " the MOU states.

As of last week, about 900 households with 2, 300 individuals remained in hotels, down from about 8, 000 people initially.

Previously, reasons for FEMA's resistance to building 1, 000 homes were not publicly clear or even known to some local government leaders who have been frustrated by the federal agency's stance.

Last resort The reason, according to FEMA, is that the agency's core mission and main capabilities don't include building new homes for emergency disaster relief.

Building new homes is an "absolute last alternative " to what the agency typically provides, said FEMA spokesperson Victor Inge.

FEMA typically deploys trailered mobile homes for disaster survivors displaced from housing, if requested by state or local government officials. Such units—commonly known as travel trailers and equipped with kitchens, bathrooms and bedrooms—could have been shipped to Maui. FEMA has thousands of these units available, and Inge said the cost to deliver and connect them to utilities isn't an issue for the agency.

Green, however, decided such homes were not a desirable or dignified choice.

As a result, the state-and county-led housing relief plan for wildfire evacuees remains more challenging and could take longer than expected to achieve.

U.S. Rep. Ed Case, during an April 10 congressional budget hearing for the U.S. Department of Homeland Security that includes FEMA, called the sought-after 1, 000 homes desperately needed because not enough existing housing on Maui is available to temporarily rehouse fire evacuees.

A large part of the rehousing effort has involved FEMA leasing existing homes, which is inflating rents and displacing some Maui residents in favor of fire survivors.

Case, who noted that Bissen was in the room for the hearing, said FEMA's help with Maui fire recovery has been tremendous and praiseworthy.

The agency as of earlier this month had approved $49 million for survivor assistance, including $21 million in rent assistance, and has spent over $1.7 billion for debris removal and other work carried out by other federal entities. FEMA also is helping to pay for the reconstruction of a state library and low-income housing project destroyed in Lahaina.

Still, Case urged Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas to have FEMA depart more from its standard approach to emergency relief housing.

"It's not really going to do the job, " Case said. "The very unique circumstances of the Maui housing market make it very difficult for you to follow your standard approach."

Mayorkas acknowledged the challenge, but was noncommittal on building more homes. "We are looking at all our options, " he said.

U.S. Rep. Jill Tokuda, whose district includes Maui, also has pressed federal officials to build more temporary homes and not rely so much on FEMA leasing existing homes.

"We need to have these temporary housing structures available, " she said in an interview. "It is going to take people years to be able to rebuild their homes."

Bissen has also let FEMA know how crucial it is to have new temporary homes for survivors of the fire that destroyed around 3, 500 residences and killed 101 people.

"A pre-existing shortage of housing units has only been exacerbated by the loss of homes due to the wildfires, " he said in a statement in March shortly after appearing before the U.S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs. "Now, paired with the unintended displacement of local tenants due to rental rates inflation and already displaced fire victims, we are in critical need of federal support to increase capacity for long-term housing options to house fire victims."

Big ask Much was made of a partnership announced in early January where Green said FEMA was designing multiple sites to house up to 500 households as part of an effort between the agency, the state, Maui County and nonprofit organizations to provide 3, 000 homes for fire survivors by July 1.

"This partnership is unprecedented and critical to our collective success as a state, " Green said in a statement announcing the partnership.

By February, local government officials were asking FEMA to build 1, 000 homes.

These homes, according to Maui County, were envisioned at three sites in West Maui and one in Central Maui. The breakdown of units was :—130 in Lahaina—213 in Kaanapali—257 in West Maui—400 in Waikapu In late January, FEMA was pursuing the Kaanapali project not far from Lahaina on 63 acres of fallow agricultural land zoned for residential use within a larger parcel long slated for an expansion of Kaanapali Resort.

But by late February, state and county officials were discouraged by what they described to Hawaii lawmakers as reluctance or push-back from FEMA over the 1, 000-home request.

Refusals Some of the frustration at the Legislature over the issue was because the state faced having to pay for many fire survivors staying in hotels where the cost for lodging plus services including meals was $1, 000 a day per household.

During a Feb. 29 Senate Ways and Means Committee briefing, Sen. Donna Kim (D, Kalihi-Fort Shafter-Red Hill ) pressed state disaster response officials over why other alternatives to hotels weren't being pursued.

Kim asked why FEMA didn't deliver travel trailers to Maui.

"The trailers are extremely costly, " said Maj. Gen. Kenneth Hara, director of the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency.

Kim then asked if the cost was more than $1, 000 a day, and Hara said he was unsure.

"Why wouldn't we be exhausting all the possibilities ?" Kim said. "It's not like we're creating this new. They've used it in other states and it's worked."

Luke Meyers, disaster management coordinator in the Office of the Governor, told Kim that sending FEMA trailer housing to Maui was cost prohibitive, but also said that it was Green's decision to not bring in FEMA mobile homes.

In a statement later, a representative of the governor said, "Governor Green objects to establishing 'refugee camps' and 'trailer parks' for wildfire survivors who have endured such devastating trauma."

During a March 27 wildfire response presentation, Green said he had talked to other state governors who accepted FEMA trailer housing for disaster assistance and regretted it.

"They ended up resulting in a lot of chaos and conflict, " Green said.

A request for Green to explain details of such trouble was not answered last week.

One highly publicized incident occurred in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 where many FEMA travel trailers deployed in Louisiana and Mississippi were found to have high levels of formaldehyde.

Green during his March 27 presentation acknowledged that it is a big ask for FEMA to build 1, 000 homes on Maui.

"We know it's difficult for FEMA to justify large builds because they are really supposed to be an emergency response agency, " he said.

Shifting plans FEMA appeared to embrace the 213-home Kaanapali project when it published a draft environmental assessment for the plan Jan. 24. Yet nearly three months later, no commitment has been made to build these homes.

Inge on April 9 said no timetable exists for possibly developing the Kaanapali site. "It's still on the table, " he said.

On Thursday, FEMA announced that land lease negotiations had resumed with the landowner of the Kaanapali site, and that design work is complete. Still, whether FEMA moves ahead with development remains uncertain.

The only home-building commitment FEMA has made to date on Maui is for 169 homes on state-owned land in Lahaina long planned for a largely affordable-housing subdivision called Villages of Leali 'i.

The site for what FEMA has named Kilohana is next to an area where the state Department of Human Services is developing 450 modular homes purchased from four manufacturers. The state's project, Kala 'iola, is expected to cost $115 million. That cost breaks down to about $118, 000 per unit on average, though 26 community buildings are also part of Kala 'iola.

An initial phase of Kala 'iola with 270 homes and some community buildings are expected to be ready for occupancy in August.

For FEMA's Lahaina project, the agency is soliciting contractors to provide and install manufactured homes ranging from under-500-square-foot units with one bedroom to under-1, 000-square-foot units with three bedrooms.

Inge said a contract is expected to be awarded May 24. A timetable for development remains uncertain.

The Rev. Ai Hironaka, resident minister of the Lahaina Hongwanji Mission, walks in the parking lot as he visits his temple and residence destroyed by wildfire, Thursday, Dec. 7, 2023, in Lahaina, Hawaii. An acute housing shortage hitting fire survivors on the Hawaiian island of Maui is squeezing out residents even as they try to overcome the loss of loved ones, their homes and their community. (AP Photo/Lindsey Wasson, File)

HONOLULU (AP) — A single mother of two, Amy Chadwick spent years scrimping and saving to buy a house in the town of Lahaina on the Hawaiian island of Maui. But after a devastating fire leveled Lahaina in August and reduced Chadwick's home to white dust, the cheapest rental she could find for her family and dogs cost $10,000 a month.

Chadwick, a fine-dining server, moved to Florida where she could stretch her homeowners insurance dollars. She’s worried Maui’s exorbitant rental prices, driven in part by vacation rentals that hog a limited housing supply, will hollow out her tight-knit town.

Most people in Lahaina work for hotels, restaurants and tour companies and can’t afford $5,000 to $10,000 a month in rent, she said.

“You’re pushing out an entire community of service industry people. So no one’s going to be able to support the tourism that you’re putting ahead of your community,” Chadwick said by phone from her new home in Satellite Beach on Florida’s Space Coast. “Nothing good is going to come of it unless they take a serious stance, putting their foot down and really regulating these short-term rentals.”

The Aug. 8 wildfire killed 101 people and destroyed housing for 6,200 families, amplifying Maui's already acute housing shortage and laying bare the enormous presence of vacation rentals in Lahaina. It reminded lawmakers that short-term rentals are an issue across Hawaii, prompting them to consider bills that would give counties the authority to phase them out.

Gov. Josh Green got so frustrated he blurted an expletive during a recent news conference.

“This fire uncovered a clear truth, which is we have too many short-term rentals owned by too many individuals on the mainland and it is b———t,” Green said. “And our people deserve housing, here.”

Vacation rentals are a popular alternative to hotels for those seeking kitchens, lower costs and opportunities to sample everyday island life. Supporters say they boost tourism, the state's biggest employer. Critics revile them for inflating housing costs, upending neighborhoods and contributing to the forces pushing locals and Native Hawaiians to leave Hawaii for less expensive states.

This migration has become a major concern in Lahaina. The Council for Native Hawaiian Advancement, a nonprofit, estimates at least 1,500 households — or a quarter of those who lost their homes — have left since the August wildfire.

The blaze burned single family homes and apartments in and around downtown, which is the core of Lahaina's residential housing. An analysis by the University of Hawaii Economic Research Organization found a relatively low 7.5% of units there were vacation rentals as of February 2023.

Lahaina neighborhoods spared by the fire have a much higher ratio of vacation rentals: About half the housing in Napili, about 7 miles (11 kilometers) north of the burn zone, is short-term rentals.

Napili is where Chadwick thought she found a place to buy when she first went house hunting in 2016. But a Canadian woman secured it with a cash offer and turned it into a vacation rental.

Also outside the burn zone are dozens of short-term rental condominium buildings erected decades ago on land zoned for apartments.

In 1992, Maui County explicitly allowed owners in these buildings to rent units for less than 180 days at a time even without short-term rental permits. Since November, activists have occupied the beach in front of Lahaina's biggest hotels to push the mayor or governor to use their emergency powers to revoke this exemption.

Money is a powerful incentive for owners to rent to travelers: a 2016 report prepared for the state found a Honolulu vacation rental generates 3.5 times the revenue of a long-term rental.

State Rep. Luke Evslin, the Housing Committee chair, said Maui and Kauai counties have suffered net losses of residential housing in recent years thanks to a paucity of new construction and the conversion of so many homes to short-term rentals.

“Every alarm bell we have should be ringing when we’re literally going backwards in our goal to provide more housing in Hawaii,” he said.

In his own Kauai district, Evslin sees people leaving, becoming homeless or working three jobs to stay afloat.

The Democrat was one of 47 House members who co-sponsored one version of legislation that would allow short-term rentals to be phased out. One objective is to give counties more power after a U.S. judge in 2022 ruled Honolulu violated state law when it attempted to prohibit rentals for less than 90 days. Evslin said that decision left Hawaii's counties with limited tools, such as property taxes, to control vacation rentals.

Lawmakers also considered trying to boost Hawaii's housing supply by forcing counties to allow more houses to be built on individual lots. But they watered down the measure after local officials said they were already exploring the idea.

Short-term rental owners said a phase-out would violate their property rights and take their property without compensation, potentially pushing them into foreclosure. Some predicted legal challenges.

Alicia Humiston, president of the Rentals by Owner Awareness Association, said some areas in West Maui were designed for travelers and therefore lack schools and other infrastructure families need.

“This area in West Maui that is sort of like this resort apartment zone — that’s all north of Lahaina — it was never built to be local living,” Humiston said.

One housing advocate argues that just because a community allowed vacation rentals decades ago doesn't mean it still needs to now.

"We are not living in the 1990s or in the 1970s,” said Sterling Higa, executive director of Housing Hawaii's Future. Counties “should have the authority to look at existing laws and reform them as necessary to provide for the public good.”

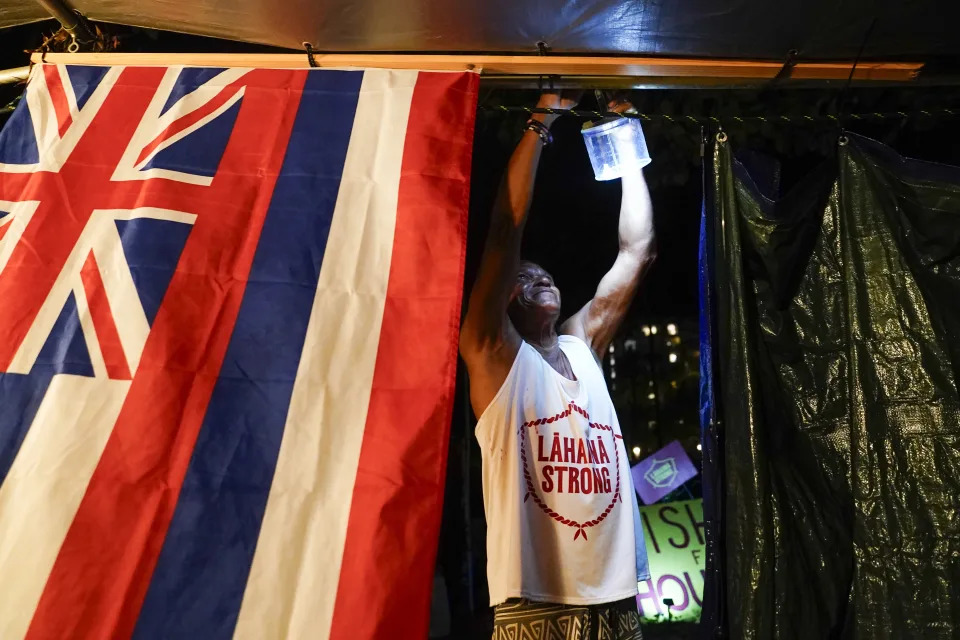

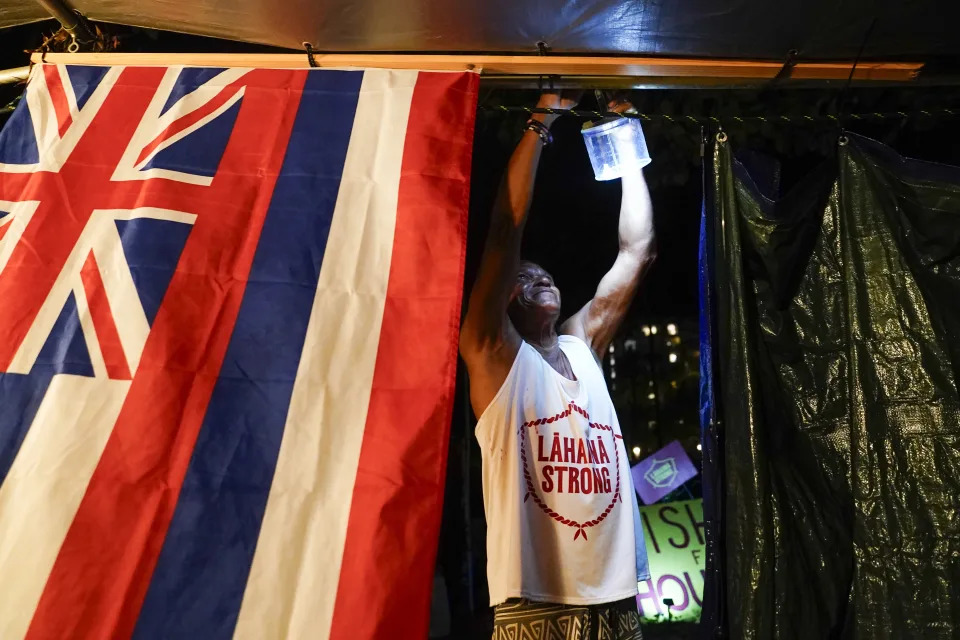

Courtney Lazo, a real estate agent who is part of Lahaina Strong, the group occupying Kaanapali Beach, said tourists can stay in her hometown now but many locals can't.

“How do you expect a community to recover and heal and move forward when the people who make Lahaina, Lahaina, aren’t even there anymore?” she said at a recent news conference as her voice quivered. “They’re moving away.”

The head of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) Yasser Arafat (left), Israeli foreign minister Shimon Peres (centre) and Israeli prime minister Yitzakh Rabin (right) jointly won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1994 after the first Oslo Accord was signed in 1993: the Oslo Agreements effectively ended Palestinians’ right to resist and entrapped them in perennial subjugation by a settler-colonial state | Reuters

The head of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) Yasser Arafat (left), Israeli foreign minister Shimon Peres (centre) and Israeli prime minister Yitzakh Rabin (right) jointly won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1994 after the first Oslo Accord was signed in 1993: the Oslo Agreements effectively ended Palestinians’ right to resist and entrapped them in perennial subjugation by a settler-colonial state | Reuters