June 8 (UPI) -- Stellar nurseries in the nearby universe come in a surprising variety of shapes and sizes, according to a new cosmic survey.

Every galaxy's stars are formed from dense clouds of gas and dust called mollecular clouds, or stellar nurseries. Previously, astronomers thought stellar nurseries were largely the same across the cosmos.

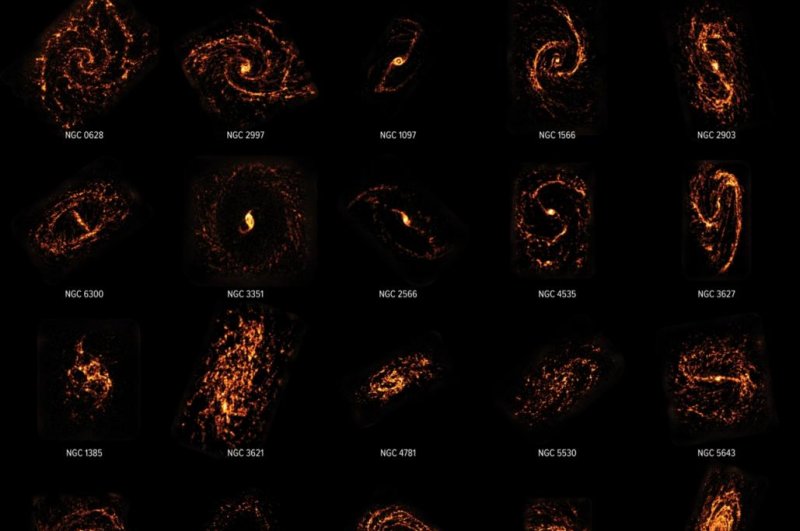

For the latest census, called the PHANGS project, scientists used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, or the ALAM telescope, located in Chile, to image 100,000 stellar nurseries in 90 different galaxies, all positioned within the nearby universe.

The results of the PHANGS survey, published Tuesday in the journal Astrophysical Journal Supplement, showed the appearance and behavior of stellar nurseries varies from place to place.

"This is the first time that we have ever taken millimeter-wave images of many nearby galaxies that have the same sharpness and quality as optical pictures," lead author Adam Leroy said in a press release.

"And while optical pictures show us light from stars, these ground-breaking new images show us the molecular clouds that form those stars," said Leroy, an associate professor of astronomy at Ohio State University.

Leroy and his colleagues likened the diversity of stellar nurseries to the differences between different cities and regions across the United States.

Though people, houses and neighborhoods share many similarities across the country, they also take on unique characteristics in different cities, states and regions.

"To understand how stars form, we need to link the birth of a single star back to its place in the universe," said study co-author Eva Schinnerer. "It's like linking a person to their home, neighborhood, city, and region."

"If a galaxy represents a city, then the neighborhood is the spiral arm, the house the star-forming unit, and nearby galaxies are neighboring cities in the region," Schinnerer said, an astronomer at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy and principal investigator on the PHANGS project. "These observations have taught us that the 'neighborhood' has small but pronounced effects on where and how many stars are born."

The survey results showed that characteristics of different stellar nurseries -- their molecular gas properties and star formation rates -- depended on where in a galaxy they were located.

Stellar nurseries in galaxy disks were different than stellar nurseries in stellar bars, as were stellar nurseries in spiral arms and galaxy centers.

PHANG images showed molecular clouds in the centers of galaxies were generally bigger, denser and more turbulent than those located in bars and arms.

The survey findings also showed the position of a nursery within a galaxy seems to influence how quickly the star formation process depletes a cloud's supply of gas and dust.

"By mapping different types of galaxies and the diverse range of environments that exist within galaxies, we are tracing the whole range of conditions under which star-forming clouds of gas live in the present-day universe," said co-author Guillermo Blanc.

"This allows us to measure the impact that many different variables have on the way star formation happens," said Blanc, an astronomer at the Carnegie Institution for Science.

Though astronomers have previously used ALMA to study stellar nurseries, previous surveys have focused on stellar clouds within single galaxies or parts of galaxies.

The new atlas contains 90 of the best maps ever made, according to study co-author Erik Rosolowsky, who said they reveal where the next generation of stars is going to form.

"The PHANGS project is a new form of cosmic cartography that allows us to see the diversity of galaxies in a new light, literally," said Rosolowsky, an associate professor of physics at the University of Alberta.

"We are finally seeing the diversity of star-forming gas across many galaxies and are able to understand how they are changing over time. It was impossible to make these detailed maps before ALMA," he said.