The last ozone-layer damaging chemicals to be phased out are finally falling in the atmosphere

Luke Western, Research Associate in Atmospheric Science, University of Bristol

Tue, June 11, 2024

The high-altitude AGAGE Jungfraujoch station in Switzerland is used to take measurements of Earth's atmosphere. Jungfrau.ch

Since the 1985 discovery of a hole in the ozone layer countries have agreed and amended treaties to aid its recovery. The most notable of these is the Montreal protocol on substances that deplete the ozone layer, which is widely regarded as the most successful environmental agreement ever devised.

Ratified by every UN member state and first adopted in 1987, the Montreal protocol aimed to reduce the release of ozone-depleting substances into the atmosphere. The most well known of these are chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs).

Starting in 1989, the protocol phased out the global production of CFCs by 2010 and prohibited their use in equipment like refrigerators, air-conditioners and insulating foam. This gradual phase-out allowed countries with less established economies time to transition to alternatives and provided funding to help them comply with the protocol’s regulations.

Today, refrigerators and aerosol cans contain gases like propane which, although flammable, does not deplete ozone in Earth’s upper atmosphere when released. However, ozone-friendly alternatives to CFCs in some products, such as certain foams used to insulate fridges, buildings and air-conditioning units, took longer to find. Another set of gases, hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), was used as a temporary replacement.

HCFCs can leak to the atmosphere from discarded fridges.

Unfortunately, HCFCs still destroy ozone. The good news is that levels of HCFCs in the atmosphere are now falling and indeed have been since 2021 according to research I led with colleagues. This marks a major milestone in the recovery of Earth’s ozone layer – and offers a rare success story in humanity’s efforts to tackle climate-warming gases too.

HCFCs v CFCs

HCFCs and CFCs have much in common. These similarities are what made the former suitable alternatives.

HCFCs contain chlorine, the chemical element in CFCs that causes these compounds to destroy the ozone layer. HCFCs deplete ozone to a much smaller extent than the CFCs they have replaced – you would have to release around ten times as much HCFC to have a comparable impact on the ozone layer.

But both CFCs and HCFCs are potent greenhouse gases. The most commonly used HCFC, HCFC-22, has a global warming potential of 1,910 times that of carbon dioxide, but only lasts for around 12 years in the atmosphere compared with several centuries for CO₂.

As non-ozone depleting alternatives to HCFCs became available it was decided that amendments to the Montreal protocol were needed to phase HCFCs out. These were agreed in Copenhagen and Beijing in 1992 and 1999 respectively.

This phase-out is still underway. A global target to end most production of HCFCs is set for 2030, with only very minor amounts allowed until 2040.

Turning the corner on a bumpy road

Our findings show that levels of HCFCs in the atmosphere have been falling since 2021 – the first decline since scientists started taking measurements in the late 1970s. This milestone shows the enormous success of the Montreal protocol in not only tackling the original problem of CFCs but also its lesser known and less destructive successor.

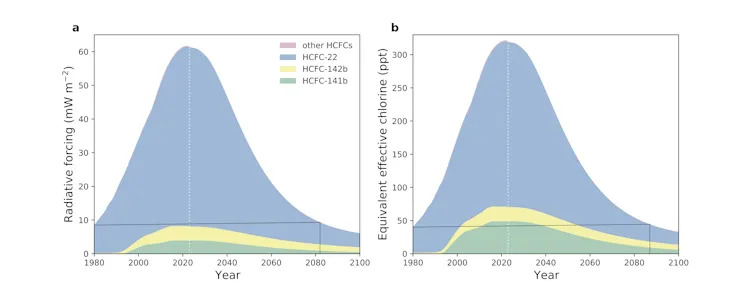

Two graphs side by side showing a the climate warming and ozone-destroying influence of HCFCs declining from 2021.

This is very good news for the ozone layer’s continuing recovery. The most recent scientific prediction, made in 2022, anticipated that HCFC levels would not start falling until 2026.

Despite HCFC levels in the atmosphere going in the right direction, not everything has been smooth sailing in the phase-out of ozone-depleting substances. In 2019 a team of scientists, including myself, provided evidence that CFC-11, a common constituent of foam insulation, was still being used in parts of China despite the global ban on production.

The United Nations Environment Programme also reported that HCFCs were illegally produced in 2020 contrary to the phase-down schedule.

In 2023, I and others showed that levels of five more CFCs were increasing in the atmosphere. Rather than illegal production, this increase was more likely the result of a different process: a loophole in the Montreal protocol which allowed CFCs to be produced if they are used to make other substances, such as plastics or non-ozone depleting alternatives to CFCs and HCFCs.

Some HCFCs at very low levels in the atmosphere have also been shown to be increasing or not falling fast enough, despite few or no known uses.

Most of the CFCs and HCFCs still increasing in the atmosphere are released in the production of fluoropolymers – perhaps best known for their application in non-stick frying pans – or hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs).

HFCs are the ozone-friendly alternative that was developed and commercialised in the early 1990s to replace HCFCs, but their role as a potent greenhouse gas means that they are subject to international climate emission reduction treaties such as the Paris agreement and the Kigali amendment to the Montreal protocol.

The next best alternative to climate-warming HFCs is a matter of ongoing discussion. In many applications, it was thought that HFCs would be replaced by hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs), but these have created their own environmental problems in the formation of trifluoroacetic acid which does not break down in the environment and, like other poly- and per-fluorinated substances (PFAS), may pose a risk to human health.

HFOs enable air-conditioners to use less electricity than competing alternatives. AndriiKoval/Shutterstock

HFOs are at least more energy-efficient refrigerants than older alternatives like propane, however.

Hope for the future

In discovering this fall in atmospheric levels of HCFCs, I feel like we may be turning the final corner in the global effort to repair the ozone layer. There is still a long way to go before it is back to its original state, but there are now good reasons to be optimistic.

Climate and optimism are two words rarely seen together. But we now know that a small group of potent greenhouse gases called HCFCs have been contributing less and less to climate change since 2021 – and look to set to continue this trend for the foreseeable future.

With policies already in place to phase down HFCs, there is hope that environmental agreements and international cooperation can work in combating climate change.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Conversation

Luke Western received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Słodowska–Curie grant agreement no. 101030750.

The world agreed to ban this dangerous pollutant — and it’s working

Sarah Kaplan, (c) 2024 ,

Tue, June 11, 2024

NEW YORK, NY - JULY 28: An air conditioner is seen in a residential windows on July 28, 2020 in New York City. With temperatures once again reaching above 90 degrees, most city dwellers rely on these units to cool their homes. The current heat wave comes only days after another stretch of warm air pushed temperatures to record levels, prompting safety warnings from the city's Office of Emergency Operations. (Photo by Scott Heins/Getty Images)More

For the first time, researchers have detected a significant dip in atmospheric levels of hydrochlorofluorocarbons - harmful gases that deplete the ozone layer and warm the planet.

Almost 30 years after nations first agreed to phase out these chemicals, which were widely used for air conditioning and refrigeration, scientists say global concentrations peaked in 2021. Since then, the ozone-depleting potential of HCFCs in the atmosphere has fallen by about three-quarters of a percentage point, according to findings published Tuesday in the journal Nature Climate Change.

Though small, that decline comes sooner than expected, scientists say - and it represents a significant milestone for the international effort to preserve the layer of Earth’s stratosphere that blocks dangerous ultraviolet sunlight.

As humanity struggles to control greenhouse gas pollution that has already pushed global temperatures to unprecedented highs, scientists said the progress on HCFCs is a hopeful sign.

“This is a remarkable success story that shows how global policies are protecting the planet,” said Veerabhadran Ramanathan, a climate scientist at the University of California at San Diego and Cornell University who was not involved in the new study.

Just over 50 years ago, researchers realized that a hole was forming in the ozone layer over Antarctica, allowing cancer-causing radiation to reach Earth’s surface. The main culprits were chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), which could destroy thousands of ozone molecules with a single chlorine atom and linger in the atmosphere for hundreds of years.

The discovery prompted countries to sign the 1987 Montreal Protocol, agreeing to phase out production of CFCs. Under the terms of the agreement, rich countries would halt production first and provide financial and technical assistance to low-income nations as they also moved away from the polluting chemicals. Production of CFCs has been banned globally since 2010.

But the most common replacements were HCFCs - compounds that have about one-tenth of the ozone-depleting potential of CFCs, but could still cause significant damage. The most commonly used HCFC also has roughly 2,000 times the heat-trapping potential of carbon dioxide over a 100-year period. So in 1992 nations agreed they would abandon these chemicals as well.

“The transition has been pretty successful,” said University of Bristol researcher Luke Western, the lead author of the Nature Climate Change study.

The United Nations estimates that the world has curbed 98 percent of the ozone-depleting substances being produced in 1990. It takes decades for those manufacturing bans to translate into fewer products sold and fewer HCFCs in the atmosphere. But Western’s research, which drew on data from two global air monitoring programs, shows that turning point has finally arrived.

HCFCs’ contribution to climate change peaked at about 0.05 degrees Celsius (almost a tenth of a degree Fahrenheit), Western said, and their abundance in the atmosphere is expected to return to 1980 levels by 2080.

“This milestone is a testament to the power of international cooperation,” said Avipsa Mahapatra, director of the Environmental Investigation Agency’s climate campaign. “To me, that signals potential to do a lot more, and it gives me climate hope.”

Mahapatra said the success of the Montreal Protocol could inspire efforts to curb planet-warming pollution - which hit another record high last year. By setting clear, enforceable targets that were cognizant of each nation’s needs, she said, the agreement propelled people to take action while remaining the only treaty signed by every country on Earth. It is credited with helping the world avoid millions of skin cancer cases and as much as a full degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) of warming.

But the work is not done, Mahapatra said. Much as HCFCs were a flawed substitute for CFCs, they have now been replaced by a new class of refrigerants - hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) - that are considered climate “super pollutants.” Although the Montreal Protocol was amended in 2016 to call for a reduction in use of HFCs, they are often used in air conditioners, refrigerators and insulation.

Ultimately, transitioning away from fossil fuels will be far more complex than curbing the production of ozone-depleting substances, Western said. The Montreal Protocol affected a relatively small industry, and it required companies only to change their products - not their entire businesses.

With climate change, “You’re up against a bigger beast in some ways,” Western said.

Are nonstick pans safe? What to know.

Kaitlin Reilly

·Health and Wellness Staff Writer

April 25, 2024

Traditional nonstick pans can contain forever chemicals. (Getty Images)

Whether you’re a seasoned cook or a newbie in the kitchen, it’s hard to beat the convenience of a nonstick pan. Your eggs scramble easily, vegetables cook evenly and — perhaps most important — you never have to worry about spending lots of time scrubbing the pan when you’re done with dinner. Yet while nonstick pans certainly have a useful function in your kitchen, they have also faced scrutiny over potential health risks, leaving some people wondering if they’re better off with cookware made of different materials. So should you be concerned about using a nonstick pan? Here’s what experts say, including whether you should replace your pans.

Why are traditional nonstick pans controversial?

Nonstick pans have been a subject of concern because they contain perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) in their coatings. PFOA is a type of PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) compound, also known as “forever chemicals,” because they don’t break down.

PFOA was once commonly used in the production of nonstick coatings — most famously, Teflon, which was invented by the company DuPont and manufactured by its spin-off company Chemours. After concerns and pressure from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) about the health risks associated with PFOAs in the early 2000s, DuPont began phasing PFOAs out of their products. This came after a 2001 class-action lawsuit that stated DuPont was well aware of the health risks associated with its chemical compound and failed to inform the public, including the communities whose health was negatively affected by the runoff from the company's manufacturing plant.

“The production of PFOA leads to long-term releases into the environment and widespread environmental contamination, including drinking water,” Tasha Stoiber, senior scientist at Environmental Working Group (EWG), tells Yahoo Life. “We know from numerous studies in both animals and humans that PFOA is linked to many health harms, including kidney cancer, testicular cancer, increased cholesterol, pregnancy-related high blood pressure and thyroid disease.”

The issue, however, was that while PFOAs were removed, they were replaced with other types of PFAS, which Stoiber says “were found to have similar health harms and persistence in the environment.” PFAS, in general, have been linked to health concerns such as increased cholesterol levels, a higher risk of kidney and testicular cancer, decreased vaccine response in children and changes in liver enzymes.

“Some pans may be labeled as not containing PFOA, but may contain other PFAS,” she explains.

Should I throw out my nonstick pan?

If you have a traditional nonstick pan made before 2015, it’s best to toss it, as there is a chance it contains PFOAs. However, even if you purchased your pan after 2015, it is possible it still contains PFAS. But does that mean you should toss out your nonstick pans? Experts are mixed here.

“The safest bet is to not purchase a pan that is marketed as nonstick, and choose cast iron or carbon steel,” says Stoiber. Choosing other types of cookware without PFAS — which can also include stainless-steel or ceramic nonstick pans, which don't use the chemicals to coat the pan since they're naturally nonstick — can reduce exposure to PFAS.

That said, A. Daniel Jones, professor of biochemistry at Michigan State University, tells Yahoo Life that there are “no studies documenting a significant risk to health arising from use of nonstick pans.” PFAS are also everywhere, he notes, explaining that exposure to them in everyday life comes from much more than just cookware. “Virtually everyone already has significant amounts of PFAS in our blood and tissues, with most of this coming from contaminated drinking water, contamination in certain foods and food packaging materials, dusts and an assortment of other consumer products,” he says.

If you are sticking with your traditional nonstick pan, you should be cautious about how you use it. A 2022 study found that a scratched nonstick pan can leave behind microplastics and nanoplastics, leading to the release of potentially harmful chemicals into your food. Just like with PFAS, people are exposed to microplastics daily and scientists aren’t yet definitively sure of the health hazards. Still, if you wish to avoid the possible risks associated with microplastics, toss your nonstick pan once it gets scratched or its surface seems to lose coating.

You also want to avoid high heat, such as putting your nonstick pan into a broiler. At high temperatures, the coating on a nonstick pan can break down and release the chemicals into the air. This is also the reason you don’t want to heat an empty pan, as it can heat up hotter and faster.

Ultimately, forever chemicals found in many traditional nonstick pans are also prevalent in the environment — and you're likely exposed to them daily. More research is needed to determine the health effects of PFAS and whether traditional nonstick pans are a particularly potent source of them. However, if you’re concerned and would rather play it safe, you can try alternative options to traditional nonstick pans.