Campus police officers are often cited as an effective tool against gun violence. But the data shows they do little to stop school shootings — and often discriminate against students of colour. Josh Marcus reports

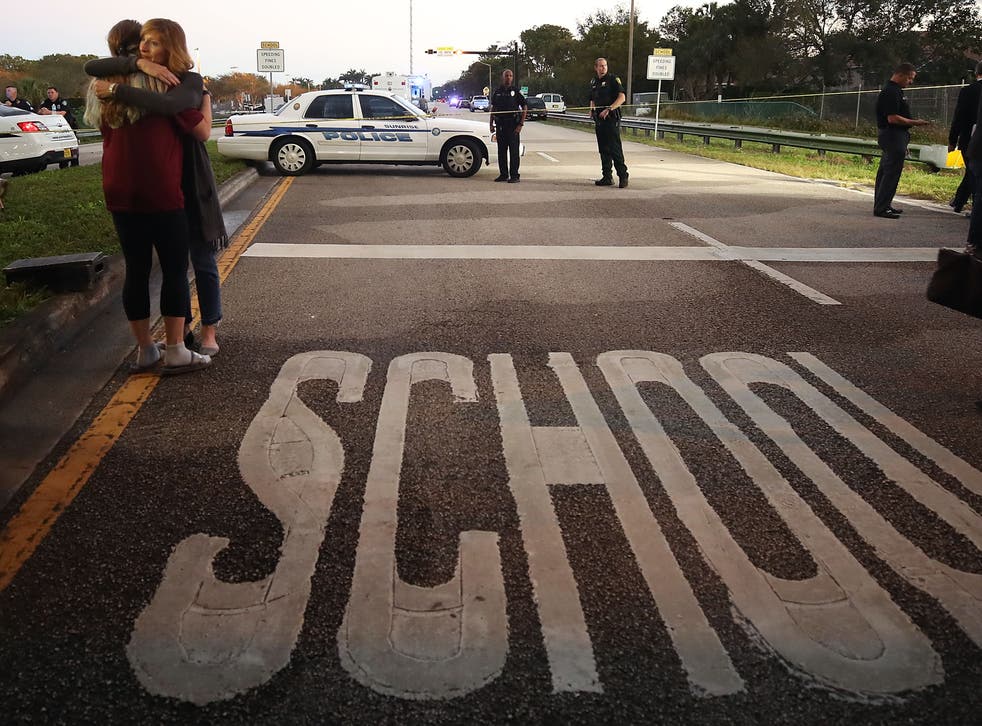

The scene of the Parkland shooting in 2018: campus police have been present for

(Getty Images)

When it comes to gun violence in America, the clock seems stuck.

The same horrific tragedies occur. The same debates are had. The same solutions are proposed. The same actions are taken. The same tragedies occur once more.

That sense of deja vu is especially palpable when it comes to one of the thorniest parts of the school safety debate: on-campus police.

On Monday, the penalty phase began in the trial of Nikolas Cruz, who shot and killed 17 people and injured numerous others in the 2018 Marjory Stoneman Douglas school massacre in Parkland, Florida.

That shooting prompted Florida to require every public school in the state to have armed security personnel on campus to stop mass shootings, even though such security was present and failed at Parkland.

Scot Peterson, then an armed deputy with the Broward Sheriff’s Office, was stationed at the school, and is now facing neglect and negligence charges for failing to enter the school building and confront Cruz. (Mr Peterson has defended his actions, saying he thought the school may have been under sniper fire, and that he followed his training.)

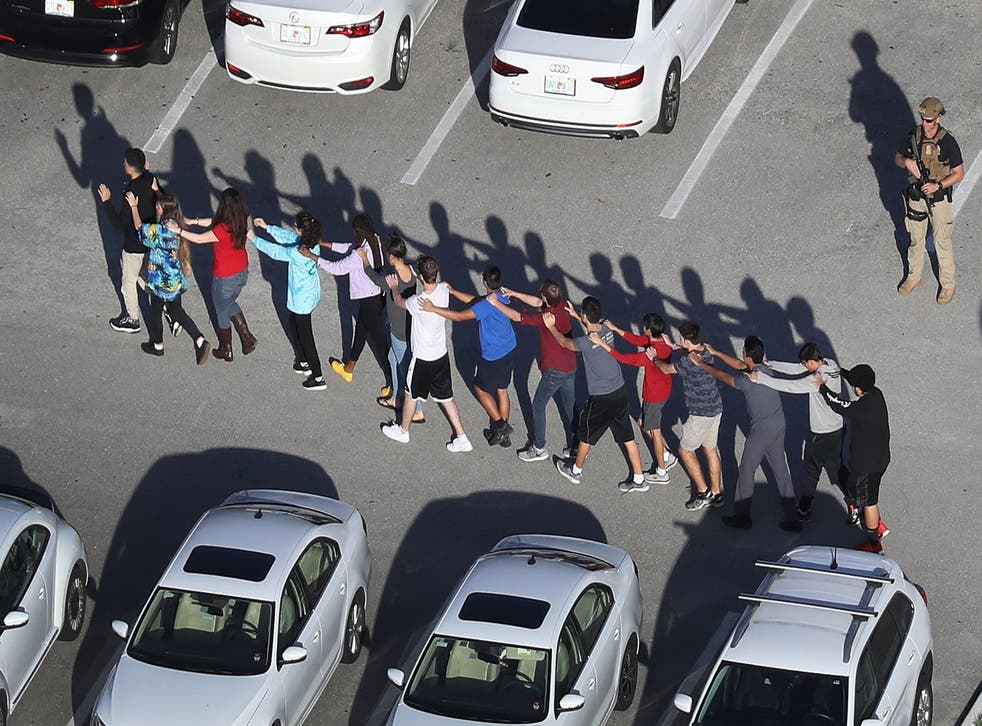

People are brought out of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School after the February 14, 2018, Parkland shooting.

(Getty Images)

But that wasn’t a new idea. The same solution had been proposed two decades earlier, after the 1999 Columbine High School massacre, where an armed school resource officers was present at the time of the shooting and didn’t stop gunmen from killing 15 people.

And it’s the same fix being put into place now, after the school shooting in Uvalde, Texas. That’s despite the fact that months of active shooter training, tens of thousands of dollars in security investments, and multiple armed police officers failed to stop gunman Salvador Ramos from entering Robb Elementary School and killing 21 people, and hundreds of officers failed to engage the 18-year-old for more than an hour as he continued shooting students inside.

The much-touted bipartisan gun deal President Joe Biden signed in June doubles funding for school police and other school security measures, investing $300m more in federal anti-violence grants.

US President Joe Biden, joined Attorney General Merrick Garland, speaks on gun crime prevention measures at the White House on June 23, 2021 in Washington DC

(Getty Images)

School resource officers are often one of the only politically acceptable, publicly popular solutions to school shootings that receive new investments.

However, even as the use of so-called “school resource officers” (SROs) has exploded in recent years, data shows the added boots on the ground have done little to stop more mass shootings on campus. Instead, by connecting schools directly to agents of the criminal justice system, school officials seem to have inadvertently imported all the racial biases of mass incarceration along with them.

Police respond to the shooting at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, Tuesday, May 24, 2022

((Uvalde Consolidated Independent School District/Austin American-Statesman via AP, File))

Few if any schools in the 1960s and 1970s had a large police presence, according to Professor F Chris Curran, director of the Education Policy Research Center at the University of Florida.

The 1980 and ‘90s changed that, with the rise of “Tough on Crime” politics and mass shootings like Columbine rocking the national consciousness. Officers were brought in to stop crime on campus, and increasingly, to protect children from gun violence.

“Following Columbine, and as we’ve seen a number of tragic school shootings, some of that narrative and reason for law enforcement has shifted to one of protecting students from external threats, more focused on the mass school shootings as opposed to the more day-to-day violence that might be present in some schools,” he told The Independent.

The Parkland shooting inspired a state law requiring armed security on all public school grounds, a first nationwide

(AFP via Getty Images)

Police are increasingly being deployed even in grade schools.

“It’s not that they’re being brought in because there’s high levels of crime in elementary schools. It’s to be there as an essential protector, to try to prevent something like Sandy Hook or like the tragedy in Uvalde.”

As of 2018, at least 58 per cent of schools had one law enforcement officer, with school police forces distributed roughly evenly between rural and urban schools, and those with and without large populations of students of colour. Since 1998, the US has spent over $1bn on school police.

It’s a trend that looks set to grow, as America once again searches for solutions after a string of mass school shootings.

Polls indicate that parents are extremely supportive of school police, with one survey finding 80 per cent backed SROs, 4 per cent more than those who wanted mental health screenings for all students.

Politicians across the political spectrum support them, too.

New Jersey governor Phil Murphy, a Democrat, ordered an increased police presence in schools after the shootings in Buffalo and Uvalde, explaining, “We will do everything in our power to ensure students, parents, and educators feel safe at school.” So did New York’s Democratic governor Kathy Hochul, ordering routine police check-ins at Empire State schools for the rest of the year.

This month, Michigan’s GOP-controlled legislature allocated $25m for school resource officers,

Days after Uvalde, US Senator for Texas Ted Cruz argued, “We know from past experience that the most effective tool for keeping kids safe is armed law enforcement on the campus.”

Periodically, such as after the 2020 mass racial justice protests, some schools like those in Milwaukee have reevaluated their relationships with police forces or cut ties, but by and large the school resource officer trend continues unabated.

SROs may have become one of America’s primary ways of stopping school shootings, but according to University of Florida’s Professor Curran, the research doesn’t actually suggest these police do much to stop school shootings from occurring.

“That’s one of the maybe disappointing takeaways and very important takeaways, given that that’s some of the justification and reason many schools are using police,” he said. “In some ways, it resonates with what we know anecdotally. You can look at Parkland right here in Florida. They had an SRO in the school and it didn’t deter and didn’t effectively stop the perpetrator from taking a lot of lives.”

Researchers analyzing school shootings between 1999 and 2018 found that the presence of SROs on campus makes no observable difference in stopping the severity of a given shooting. Another team found that the presence of school police may actually make things worse. Hamline University criminal justice professor Jillian Peterson looked at 40 years worth of school shootings, covering 133 incidents from the 20 years before and after 1999’s Columbine massacre, and found that there were three times as many people killed during these events when there was an armed office on the scene.

Explanations for these trends vary. Some suggest that school shooters arm themselves more heavily if they know they’ll face armed police. Others speculate that those in a mental state to carry out a school shooting simply don’t care that they could be shot by an armed officer. There’s also the fact that, according to Prof Curran, police in schools are often outgunned by school shooters, and only accurately shoot back about a third of the time under high stress.

“Even highly trained people may not be effective at neutralising the threat immediately,” he said.

What the research does show, however, is that school police mirror larger trends in the criminal justice system, and focus disproportionate attention, and at times violence, on students of colour.

Researchers at the University of Albany and RAND Corporate found in 2021 that SROs don’t effectively prevent school shootings or gun-related incidents, but increase the use of suspensions, expulsions, police referrals, and criminal arrests — punishments directed at Black students two times more often than white ones.

Other research indicates schools with SROs see a decrease in high school graduation and college enrollment rates, while Black students experience the largest increase in discipline.

According to the US Department of Education, Black students without disabilities made up 30 per cent of school-related arrests in 2017, twice their share of the public school population, while white students were comparatively under-represented. The Center for Public Integrity, meanwhile, has found that in 46 states, Black students are referred to law enforcement at higher rates than all students, even though no US state has a majority Black population.

Research also suggests Black girls in particular face even worse disproportionate punishment by school police.

That’s just in the aggregate. One interaction with police can change the trajectory of a young student’s life, as portrayed in the 2021 documentary On These Grounds, about a 2015 viral video of a school resource officer in Columbia, South Carolina, violently arresting a girl in class.

On 15 October, 2015, Spring Valley High School school resource officer Ben Fields was called into a math class to remove Shakara Murphy, who was supposedly misbehaving. Video captures the officer briefly asking Ms Murphy to stand up. When she remains in her chair, seconds later he flips her backward over the chair, then hurling her across the room before kneeling on top of her and arresting her, leaving her with rug burn on her face and a hairline facture in her wrist.

Another student, Niya Kenny, who filmed the encounter and challenge Mr Fields’s use of force, was also arrested and temporarily sent to an adult jail.

“I was in disbelief. I know this girl got nobody. I couldn’t believe this was happening. I’ve never seen nothing like that in my life, a man use so much force on a little girl, a big man like, 300 pounds of full muscle. I was like no way, no way, you can’t do that to a little girl,” she told local news at the time.

Both girls were booked under an archaic early 1900s “disturbing schools” law that made it a misdemeanour to disturb school in any way. The law has roots in the Jim Crow South, when it was first introduced to prevent flirting with white women at a women’s college, and was later used to quell civil rights protests in schools in the 1960s.

What was missing from the video, and in the minds of many critics, from the whole situation, was a larger context or any sense that extreme force shouldn’t be used on a teenager simply because she wouldn’t stand up out of a desk.

The incident began when Ms Murphy, a foster child, got in a disagreement with her teacher, who was barring her from accessing her legally protected school disability assistance plan during a math test. Officer Fields, a hulking powerlifter, actually knew about Ms Murphy and her background, and had stopped other students from picking on her in the past. That didn’t stop him from tossing her across the room like a sack of trash.

“What was going on in his mind that he had to throw me like that?” Ms Murphy told filmmakers in On These Grounds. “I want other kids to be able to go to school, get their education, and be safe and feel like that’s not going to happen to them.”

Both Ms Murphy and Ms Kenny, as is typical with many students who face police discipline, never returned to Spring Valley High School.

Ben Fields, who was fired after the incident but did not face any criminal charges, argues he wasn’t being racist, and that he was actually following department use-of-force policy.

In the chaos of the arrest, Ms Murphy said she reached out to find a handhold, accidentally striking the school resource officer in the face. The former officer, who is white, interpreted it as an intentional punch, which would’ve entitled him to use a baton or an attack dog against Ms Murphy, who is Black, according to a department use-of-force memo at the time.

“If I had took out a baton and hit her with it, does that look good? If I had called a canine on her, does that look good? What is this, 1960?” Mr Fields says in the film. “I did what I thought was best in the situation, based on my training.”

He also told filmmakers the so-called “schools-to-prison pipeline,” a concept popularised by scholars like Michelle Alexander, is “one of the biggest hoaxes I’ve ever heard of.”

At the time of the viral video, according to the ACLU, 71 per cent of students in South Carolina referred to the Department of Juvenile Justice were Black, a rate nearly three times greater than their share of the overall population. Spring Valley’s arrests of students had an even higher percentage of African-Americans, an astonishing 88 per cent.

Activists like Vivian Anderson, founder of EveryBlackGirl, a group that supports young Black women in the face of police violence and other forms of discrimination, say schools should prioritize counseling and other social services over policing.

“These are two girls. What happens when we start pushing young people out of school? We know what it means to silence trauma. That’s how we get all our -isms. Our alcoholism, all our addictions,” she says in the documentary about Spring Valley. “This should never happen to any child.”

In 2019 the ACLU has estimated that millions of children in US public schools have police on school grounds, but no access to a social worker, mental health counselor, or nurse.

There are some in Washington who are trying to change this resource gap.

In June, a group of Democrats in Congress introduced the Counseling Not Criminalization in Schools Act, which would shift federal resources away from police and towards more social services.

“Since Columbine, our country has approached the problem of school shootings by funding school police,” Representative Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts said at a June hearing. “A billion dollars, thousands of school police officers — when 90% of our students can’t access a school nurse or social worker or guidance counselor — and more than two decades later, we find ourselves in the same spot as before. Only in America.”

As Professor Curran, the University of Florida researcher, points out, school police are only a recent invention in the US. If schools can shift so much to accommodate them, it follows that schools can change in other ways if people decide school policing is not living up to its promises.

“We have a history of having schools without police,” he said.

His personal view, after having worked with parents, schools, and officers themselves, is that it’s a highly nuanced issue, and one where community control is vital. That would factor in historical experiences between communities and police, he says.

“It’s perfectly possible to imagine a world in which schools have no police for many nationwide,” he said.

It’s possible, but after another summer of school shooting tragedies, it remains to be seen whether it’s likely.