New sabre-tooth predator precedes cats by millions of years

ANOTHER AMAZING FIND FROM THE MUSEUM STORAGE ROOM

The fossil, housed in the San Diego Natural History Museum's paleontology collection, offers a window into what the Earth was like during the Eocene Period, more than 40 million years ago. The specimen includes a lower jaw and well-preserved teeth, giving us new information about the behavior and evolution of some of the first mammals to have an exclusively meat-based diet.

"Today, the ability to eat an all-meat diet, also called hypercarnivory, isn't uncommon. Tigers do it, polar bears can do it. If you have a house cat, you may even have a hypercarnivore at home. But 42 million years ago, mammals were only just figuring out how to survive on meat alone," said Dr. Ashley Poust, postdoctoral researcher at the San Diego Natural History Museum (The Nat). "One big advance was to evolve specialized teeth for slicing flesh—which is something we see in this newly described specimen."

This early meat-eating predator is part of a mysterious group of animals called Machaeroidines. Now completely extinct, they were not closely related to today's living carnivores. "We know so little about Machaeroidines, so every new discovery greatly expands our picture of them," said coauthor Dr. Shawn Zack of the University of Arizona College of Medicine. "This relatively complete, well-preserved Diegoaelurus fossil is especially useful because the teeth let us infer the diet and start to understand how Machaeroidines are related to each other," said Zack.

Zack, Poust, and their third coauthor Hugh Wagner, also from The Nat, named the predator Diegoaelurus vanvalkenburghae. The name honors San Diego County where the specimen was found and scientist Blaire Van Valkenburgh, past president of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, whose foundational work on the evolution of carnivores influenced this research.

About the discovery

D. vanvalkenburghae was about the size of a bobcat, but with a downturned bony chin to protect its long upper sabre teeth. It would have been a powerful and relatively new kind of hunter.

"Nothing like this had existed in mammals before," said Poust. "A few mammal ancestors had long fangs, but Diegoaelurus and its few relatives represent the first cat-like approach to an all-meat diet, with sabre-teeth in front and slicing scissor teeth called carnassials in the back. It's a potent combination that several animal groups have independently evolved in the millions of years since."

This animal and its relatives represent a sort of evolutionary experiment, a first stab at hypercarnivory—a lifestyle that is followed today by true cats. With only a handful of fossil specimens from Wyoming and Asia, the machaeroidines are so poorly understood that scientists weren't even sure if there were multiple species living within the same time period. "This fossil finding shows that machaeroidines were more diverse than we thought," says Zack. "We already knew there was a large form, Apataelurus, which lived in eastern Utah. Now we have this smaller form, and it lived at approximately the same time. It raises the possibility that there may more out there to find."

In addition to this overlapping existence, Poust points out they may have coexisted with other sabre-toothed animals. "Diegoaleurus, though old, is the most recent of these machaeroidine predators. That puts it within striking distance of the time that the next cat-like animals arrived in North America, the nimravids or sabre-tooth false-cats," he said. "Did these groups ever meet, or even compete for space and prey? We don't know yet, but San Diego is proving to be a surprisingly important place for carnivore evolution."

About the Santiago Formation

The fossil comes from San Diego County in southern California, at a location first discovered in the 1980s by a local 12-year-old boy. Since then, "Jeff's Discovery Site" has become an important fossil bed within a larger group of rocks called the Santiago Formation. Fossils of an entire ecosystem have been discovered in these 42 million-year-old rocks, painting a picture of a very different San Diego than the one we know today. Though largely inaccessible, these important fossil beds are occasionally exposed by construction projects and road expansions, allowing scientists from The Nat to keep digging for evidence of California's ancient, tropical past.

"Not only was San Diego further south due to tectonic plate movements, but the Eocene was a wetter, warmer world," said Poust. "The Santiago Formation fossils show us a forested, wet California where tiny rhinos, early tapirs, and strange sheep-like, herbivorous oreodonts grazed under trees while unusual primates and marsupials clung to the canopy above. This richness of prey species would have been a smorgasbord for Diegoaelurus, allowing it to live the life of a specialized hunter before most other mammals."

The article, "Diegoaelurus, a new machaeroidine (Oxyaenidae) from the Santiago Formation (late Uintan) of southern California and the relationships of Machaeroidinae, the oldest group of sabertooth mammals," is published in PeerJ.

About the 3D model

The jaw of the newly named meat-eater is available to view in 3D for free on the San Diego Natural History Museum's website.

To access this 3D model and view in your browser, go to https://3dfiles.sdnhm.org/api/?specimen=38343&name=38343_Dentary_RT&extension=ctmGrad student finds a new saber-toothed species in a museum collection

More information: Shawn P. Zack et al, Diegoaelurus, a new machaeroidine (Oxyaenidae) from the Santiago Formation (late Uintan) of southern California and the relationships of Machaeroidinae, the oldest group of sabertooth mammals, PeerJ (2022). DOI: 10.7717/peerj.13032

Journal information: PeerJ

Provided by PeerJ

Mysterious 'hypercarnivore' with blade-like teeth roamed California 42 million years ago

The hypercarnivore may have hunted tapirs and tiny rhinos.

By Nicoletta Lanese

LIVE SCIENCE

The fossil includes a near-complete lower jawbone and a set of well-preserved teeth, according to a new study, published Tuesday (March 15) in the journal PeerJ. Paleontologists at the San Diego Natural History Museum (The Nat) originally collected the specimen in 1988 from a site known as the Santiago Formation in Oceanside, a city in San Diego County, California. The geological formation is estimated to be about 42 million years old, so fossils from the site date back to the Eocene epoch (55.8 million to 33.9 million years ago), according to the American Museum of Natural History.

When the fossilized jawbone was initially discovered, "it had been very properly identified as a meat-eating animal," said study co-author Ashley Poust, a postdoctoral researcher in vertebrate paleontology at the Nat. The specimen bears "big, slicing, scissoring teeth" that are ideally suited for shredding fresh meat, rather than for crunching through nuts or gnawing on bones, for instance, Poust said.

Sponsored Links

The museum paleontologists originally thought these formidable teeth might belong to a nimravid, a type of cat-like hypercarnivore, an animal whose diet consisted mostly of meat. The nimravids are often called "false saber-toothed cats," as they resemble the famous felines but don't belong to the Felidae family as true cats do, Live Science previously reported.

Related: My, what sharp teeth! 12 living and extinct saber-toothed animals

However, study co-author Hugh Wagner, a paleontologist at the Nat, later suggested that the jawbone might belong to a more mysterious group of hypercarnivores with scant representation in the fossil record: the machaeroidines. Remains of these strange beasts have been uncovered only at select sites in Asia and North America, and prior to the new study, only 14 specimens had ever been found, according to the PeerJ report. The now-extinct group includes the earliest known saber-toothed mammalian carnivores, which are not closely related to any living carnivores.

Two of these specimens — a partial skeleton and a jawbone — were discovered in Wyoming and Utah and described in prior papers by the study's co-first author Shawn Zack, an assistant professor at the University of Arizona College of Medicine and an expert in ancient carnivores. For the new paper, Zack, Poust and Wagner teamed up to reexamine the perplexing carnivore jawbone in the Nat's collection and determine, once and for all, whether it belonged to a machaeroidine.

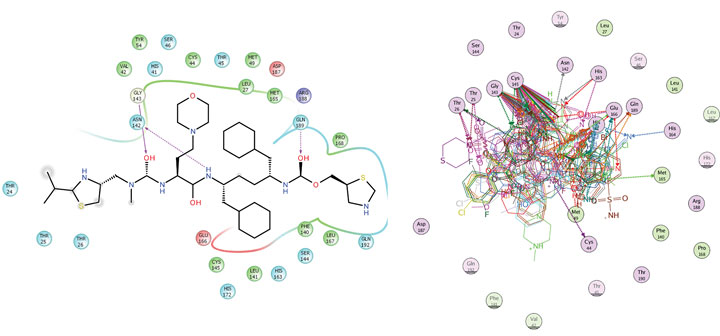

The team snapped photos of the fossil from many angles in order to construct a detailed 3D model of the bone and teeth, and after a thorough examination, they confirmed that the specimen was not only a machaeroidine, but a never-before-seen genus and species of machaeroidine.

They named the newfound creature Diegoaelurus vanvalkenburghae in honor of San Diego County, where the specimen was found, and scientist Blaire Van Valkenburgh, a past president of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology whose work greatly influenced scientists' understanding of carnivore evolution.

"Finding this particular group was pretty surprising," because no other machaeroidine specimens in the U.S. had been found west of the Rocky Mountains, Poust told Live Science. "We didn't know that these occurred out here at all."

Related: Ancient footprints to tiny 'vampires': 8 rare and unusual fossils

Based on the size of the jawbone, the researchers determined that D. vanvalkenburghae was about the size of a bobcat, according to the study. The animal carried blade-like, slicing teeth in the back of its mouth and had "sort of reduced teeth in the front — it's totally lost the first [tooth] behind its lower canine," Poust said. Modern cats also have this gap behind their lower canines, to make space for their large upper canines to bite down, he noted. In addition to this gap, D. vanvalkenburghae had a downturned, bony chin that also would have helped to accommodate its impressive saber teeth.

About 42 million years ago, D. vanvalkenburghae would have lived in a very different environment than can be found in San Diego County today, Poust noted.

The Eocene kicked off with a period of extensive warming, which fueled the growth of hot, humid rainforests around the world, according to the American Museum of Natural History. Fossils recovered from Santiago Formation suggest that the lush rainforests of ancient Southern California were once home to lemur-like primates, marsupials, boar-size tapirs and tiny rhinos. In theory, D. vanvalkenburghae may have preyed on these animals, although the predator's exact diet is unknown, Poust said.

The new species helps fill out the sparse machaeroidine fossil record, but it also raises new questions about the cat-like predators, Poust said.

For example, did D. vanvalkenburghae ever coexist and compete for prey with nimravids? The oldest nimravid remains found in the U.S. are roughly 5 million years younger than the newly identified D. vanvalkenburghae fossil, so it would partially depend on when the machaeroidine went extinct. The exact timing and reason for this extinction also remain mysterious, although it's clear that machaeroidines died out many millions of years before the emergence of true saber-toothed cats (Smilodon), Poust noted.

Originally published on Live Science.

.jpeg)