Unproven technologies, unknown risks: Top SA climate scientists sceptical humanity can ‘geoengineer’ its way out of climate crisis

On a globe already pockmarked by extreme weather events, a mere .4°C away from the thresholds of “dangerous climate change”, nations as well as non-state actors are increasingly looking to technology to pivot humanity from self-imposed disaster on to the path toward salvation.

Scientists say, however, that while possible, there are immense political, economic, ecological, ethical and other societal considerations to be aware of when tinkering with global climate.

Much like South Africa, where multi-year droughts and heat waves are expected to be the most significant climate-change-related challenge, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is also threatened by extreme temperatures and reduced rainfall. Its National Center of Meteorology has been testing “rain-enhancement” technology to “seed” clouds and tackle the impacts of climate change head-on.

High above the dunes and cityscapes of the UAE, in the skies above Abu Dhabi and Al Ain, drones have been flying among the clouds, releasing electrical charges aiming to merge water droplets, form precipitation and ultimately trigger rainfall according to Gulf Today.

In the absence of complete abeyance of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions, technological alternatives are being proposed to either halt or reverse the heating of the planet. When these technologies and techniques reach a global scale, they comprise what is referred to as “climate geoengineering” (GE). The University of Oxford defines geoengineering as “the deliberate large-scale intervention in the Earth’s natural systems to counteract climate change”.

Professor Bruce Hewitson, South Africa national research chair on climate change and director of the Climate System Analysis Group (CSAG), told Daily Maverick he has reservations about geoengineering.

“I’m deeply sceptical of geoengineering, not because it’s not feasible, but because it has very dangerous potential consequences. I think it is very valid to do research on it so we understand geoengineering options better. So doing research to look at its limits and viabilities is very valid, but I am deeply sceptical that it will ever be a viable option.”

He used SRM as an example saying: “Solar radiation management is managing the amount of sun that is reaching the surface and there are different ways of doing that, but if you do that in one location, if you do something that reduces the sunlight let’s say over the Western Cape, then that has an impact on how the atmosphere responds and that is going to have a change on the climate outside of the Western Cape.”

His scepticism, Hewitson explained, was because of the unknown nature of the potential impacts of geoengineering and the interconnectedness of the climate system.

“We’re in a coupled climate system, so whatever you do in one location has a consequence elsewhere. These other consequences are very difficult to map out at this point and we don’t fully understand them, and the problem is that in every region of the world the society is calibrated to the climate it receives. Now if you change the climate, you’re going to disturb the structure of society, you’re going to impact that society whichever way you change the climate,” he said.

“So geoengineering has some very high potential to cause negative impacts, negative consequences while its primary objective of trying to reduce the energy in the atmosphere, trying to reflect sunlight or whatever way you try to approach it — the primary objective is technically feasible. There are a lot of technical scalable options available to us, but the potential consequences of taking those actions are very, very dangerous.”

Broadly defined, proposed geoengineering techniques fall into one of two categories:

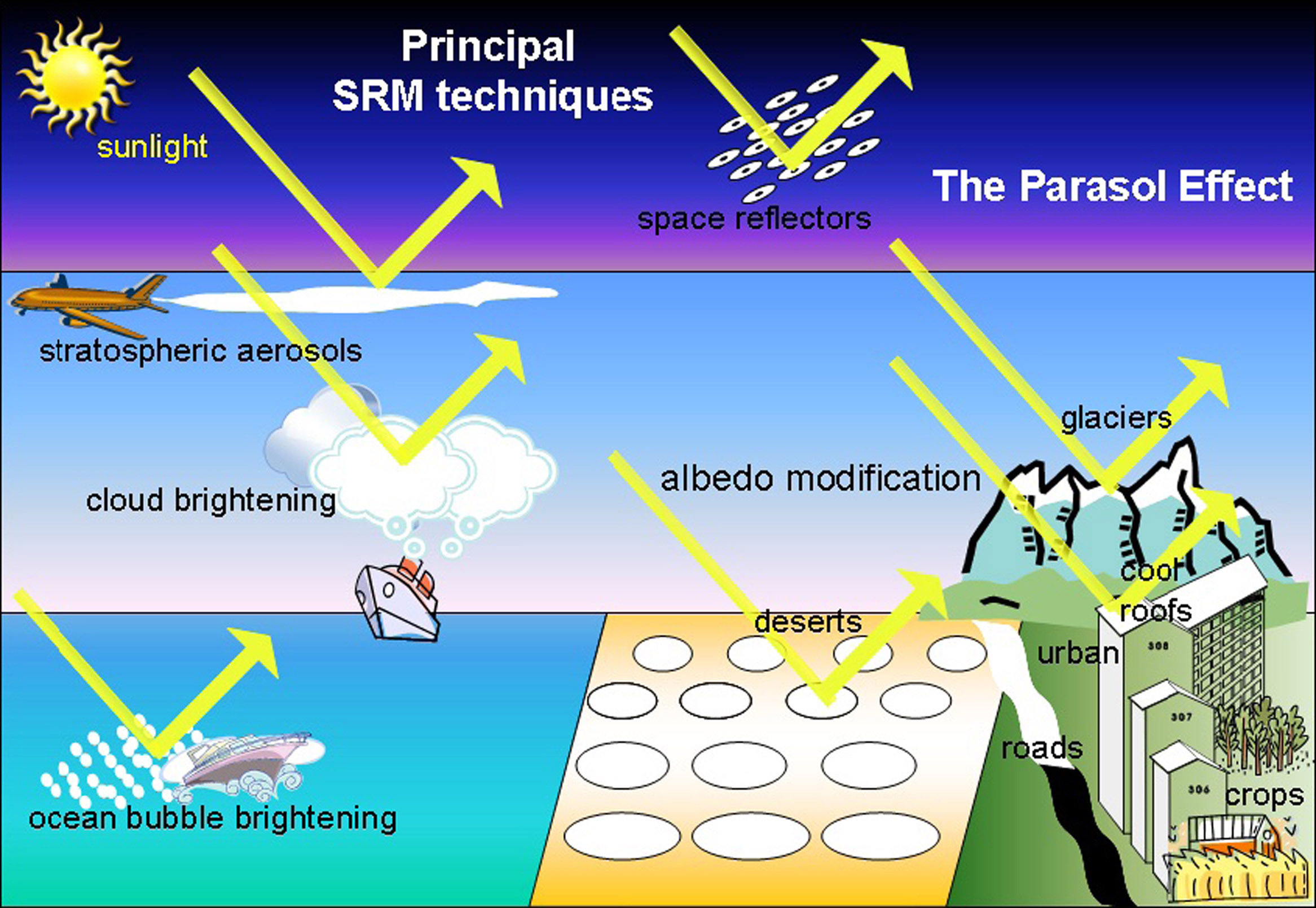

The first is solar radiation management (SRM). The Royal Society, in a report, explains that SRM “refers to proposals to cool the Earth by reflecting a small percentage of inbound sunlight into space, in order to reduce global warming”.

A prominent SRM technique proposal is stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI). SAI is a proposed geoengineering technique that seeks to “engineer global climate through the deliberate injection of aerosols into the stratosphere”. According to a report, the intent is to cool the planet by reflecting sunlight into space.

The oceans have also piqued the interest of climatologists and researchers in the geoengineering space, with marine cloud brightening (MCB) proposed as another SRM technique. MCB is a proposal to whiten the clouds above the oceans to reflect more sunlight into space.

A Royal Meteorological Society paper explains that MCB might involve “using automated ships to spray droplets of seawater into the marine boundary layer where they evaporate to form an elevated concentration of sea-salt aerosols which nucleate higher concentrations of cloud droplets in marine clouds, thereby increasing their reflectivity”.

(Source: ScienceDirect)

Dr Pedro Monteiro, head of Ocean Systems and Climate at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, told Daily Maverick that, in a way, SRM is “the most problematic of all the interventions” because of the principle it works on.

Consistent with the views expressed by Hewitson, he explained that solar radiation management cannot be used as a local intervention. It’s hard to reduce the sunlight in just one spot.

“The main problem with it is that the impacts that SRM have regionally are very uncertain and it is quite possible that in some areas there could be positive outcomes, ie, cooling. It could also just as much be possible that there could be very negative effects in areas, and the models are at this stage not able to provide us with the confidence level that would make the intervention viable. So the point is really the uncertainty around the global versus regional impacts of SRM.”

The other main problems are that the technologies don’t yet exist at scale and that if they were stopped, the benefits of their use would swiftly disappear, Monteiro said.

“So, on three levels: the unproven technologies, the unknown risks and the lack of a governance system that would ensure multidecadal continuity [make] SRM something that is pretty much off the table as an intervention.”

The second category of geoengineering techniques is the much-vaunted carbon dioxide removal (CDR). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defines CDR simply as “the process of removing CO2 from the atmosphere”.

The IPCC report explains that there are two main types of carbon dioxide removal, namely: “enhancing existing natural processes that remove carbon from the atmosphere (eg, by increasing its uptake by trees, soil, or other ‘carbon sinks’) or using chemical processes to, for example, capture CO2 directly from the ambient air and store it elsewhere (eg, underground)”.

Monteiro said that “CDR is in essence… reversing the emissions of CO2 over the past century”.

Monteiro, an author in the recent “code red for humanity” IPCC report, said that, “We now understand enough about the carbon climate system to be able to say confidently that the only way we will stay under the 1.5-degree temperature objective is through the implementation of CDR at the scale that has an impact on the global CO2 concentration in the atmosphere.

“So that makes it sort of a prime approach. In other words, to get us into a safe climate space, CDR is sort of the broad box that we have that is probably workable. However, the problem is that there are no proven CDR techniques that scale up to the level that is required at this stage,” he said.

“I want to really emphasise that there are two stages for getting to 1.5°C and keeping us there. The first stage is what’s called net zero and to get to net zero we need to stop CO2 emissions. In order to stay at 1.5°C we need to go into negative emissions in the second half of the century and this is where CDR comes in.

“CDR are central to implementing negative emissions in the second half of the century and beyond. So from a global and a South African perspective, the big challenge is that there are no proven techniques at this stage that scale up to the required global impact.”

In an article in Nature, the authors argue that “current mitigation efforts and existing future commitments are inadequate to accomplish the Paris Agreement temperature goals”. The “Long Term Global Goal” of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change is to restrict global warming to values well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels because above these levels aspects of climate change become increasingly dangerous in terms of impact.

The authors in Nature continue that “although research indicates that several techniques may eventually have the physical potential to contribute to limiting climate change, all are in early stages of development, involve substantial uncertainties and risks, and raise ethical and governance dilemmas. Based on present knowledge, climate geoengineering techniques cannot be relied on to significantly contribute to meeting the Paris Agreement temperature goals.”

Hewitson told Daily Maverick that geoengineering is only being discussed “because society is not willing to engage with our fossil fuel dependency”.

“If we could change our fossil fuel dependency and our emissions, these geoengineering options would be far less needed to be thought about and discussed. It’s like trying to treat someone for cancer who has been smoking but they refuse to stop smoking. It’s illogical. You can do it. You can treat someone who has cancer from smoking but really they should stop smoking. Geoengineering is trying to treat somebody who is perpetuating the cause of the problem.”

The real geoengineering solution, he said, is for society to change how we use and generate our energy systems and to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. OBP/DM

This article first appeared on Daily Maverick and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.