The Dreadnought After Next

This article appears courtesy of CIMSEC and The Royal Navy. It was the first place, Gold Prize-winning essay of the First Sea Lord’s Essay Competition and may be found in its original form here.

[By Chris O’Connor]

In 1906, the battleship HMS Dreadnought was commissioned. An engineering marvel at the time, it completely changed the playing field of naval warfare and made previous classes of battleships and armoured cruisers obsolete overnight. Its advantage was not new technology but using technologies in a new combination that had never been done before. It created such an epochal shift in warship design that the battleships built preceding it were retroactively described as ‘preDreadnoughts.’1 In the next couple of years, a new HMS Dreadnought will go to sea. It will contain technologies that were the realm of science fiction when the battleship Dreadnought was commissioned – leveraging the atom for electrical power and weapons, operating with thinking machines, and using sound and radio waves to detect targets unseen by the eye.

The change of technologies between Sir Jackie Fisher’s Dreadnought of 1906 and its namesake two generations later (with the nuclear-powered attack submarine of the same name in between) did not make warships obsolete, rather, it completely changed the perception of what a warship was. Submarines were not considered ‘warships’ by many in the Royal Navy at the turn of the 20th century – when Sir Jackie experimented with them as the Commander-in-Chief of Portsmouth. Dismissed as ‘Fisher’s Toys,’ they were considered ‘unmanly, unethical, and ‘un-English.’2 If this sounds familiar, it is because this same kind of thinking, a fear of the new technology being so different that it is not ‘right,’ is used today to describe uncrewed platforms and other autonomous systems instead of ships operated by stalwart human sailors. The battleships of today are museums and not the capital ships of nations because they were overcome by new technologies and operational concepts. Warships still exist, but they are markedly different.

This historical perspective of maritime warfare innovation calls for a rephrasing of ‘will warships be obsolete?’ Instead, we should ask ourselves ‘What will make current warships obsolete?’ That way, we can examine the technologies that are just coming to the fore and begin thinking now about how warships will evolve, and yes, their form and function will not look like anything before.

Modern missiles and Directed Energy Weapons (DEW) alone will not bring about this change. New anti-ship missiles with longer ranges, smarter seeker heads, and hypersonic speeds will certainly force operational changes and necessitate new countermeasures for warships on the surface (and eventually below the surface). DEW will be part of every physical domain of warfare, as laser and microwave weapons will be employed from everything from satellites to Marines on the ground. These weapons will lead to an evolution in warship design to add magazines and launchers for the new missiles and increased power generation for the DEW. These ideas are all rolled into the ‘Dreadnought 2050’ concept that was publicised in 2015,3 but in the intervening years between then and now, a new forcing function has emerged that will cause a drastic rethink about the concept of a ‘warship.’

The new paradigm in naval warfare will be triggered by the simple fact that a warship of any size will no longer be able to hide on the surface of the oceans. Persistent multispectral sensing from space with military and commercial satellites already complicate efforts to create uncertainty for potential adversaries. Imagery taken daily of bases and harbours can discern with ever greater clarity the readiness and deployment schedules of navies. This pales in comparison to the ramifications of when these constellations of satellites are aided by deep learning algorithms that will be able to provide daily positions of warships at sea. In just the past year, Russian military equipment aiding the Kremlin in its invasion of Ukraine and a Chinese spy balloon were both tracked by these revolutionary means – satellites from the commercial company Planet feeding their image sets to generative artificial intelligence.4

When surface warships can be tracked this way, they will be constantly targeted and will most likely lose the element of surprise. Submarines are safe from this technology, for now. Even if a ship was able to develop some sort of countermeasure to hide itself and its various signatures (to include its wake), modern ships still rely on fuel for their engines, parts for their systems, and food for their crew. A carrier strike group (CSG) or surface action group (SAG) will give away its location simply through the replenishment ships they require to operate. To win the fight in this sensing environment, the warship will not be over a hundred metres long with scores of people onboard, it will have to be altogether different.

A warship is nothing more than a cluster of capabilities working in concert to fight. Sensors, weapons, propulsion, command and control, communications, and decision-making processes all linked together with a common set of missions and its embedded tasks. Modern warships have all of most of these functions physically located in one hull, but they do not have to be. Instead of a large ship that has offloaded weapons and sensors (like an aircraft carrier), a warship of many small optionally crewed systems would replace that big ship altogether. If hit with a hypersonic missile or fried with a microwave pulse, the ship would be able to reconstitute with varied components.

The crew and command structure would look very different, too:

“A small crew would embark a ship, or series of ships, serving in a variety of modalities as expert controllers, emergency maintainers, and expeditionary operators…moving from independent expeditionary command with a manned crew, to embarking on a mothership or series of motherships supporting unmanned operations.”5

These smaller distributed ships will build up to units that will have humans on the loop but will have to rely on autonomy to do a lot of the fighting. In doing so, a navy will be built of units that are closer to an aviation squadron with one commander, whose span of control is over many smaller assets. These together will be the ‘warship’ that will adapt every time they are employed, as the systems learn from past operations and enemy activity and will swap out with others of different payloads. The evolving capability would be akin to changing the battleship HMS Dreadnought’s turrets every underway – that is how integral these smaller vessels will be to the coherent whole of the unit. There are two benefits to this model; one, the ‘distributed force will pose a vast array of interlocking firepower, making it less clear to the adversary which elements… pose the most pressing threat,’ and two, ‘impos[ing] more kill chains for the adversary to manage.’6 This way of fighting at sea will be the only way to manage when larger warships will be rendered obsolete by their signatures.

When Sir Jackie Fisher recognised the disruptive potential of submarines he did not care if they were cowardly or underhanded, he only cared that they worked.7 He had the clarity of vision to examine warfare from the undersea while working on a super battleship that would be revolutionary in its own right. He was quoted as saying “I don’t think it is even faintly realised that the immense impending revolution with which submarines will effect as offensive weapons of war.” The crewmembers of the two submarines named Dreadnought realised this revolution. How soon will we realise the revolution of autonomous systems that will lead to a warship of the future – the Dreadnought after next?

Cdr. Chris O’Connor is a U.S. Naval Officer at NATO Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe and Vice President of CIMSEC.

These views are presented in a personal capacity and do not necessarily represent the official views of any government or department.

References

1. Jesse Beckett, ‘The Enormous Early 20th Century Pre-Dreadnought & Dreadnought Battleships’, War History Online,

25/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3pRpS6K.

2. Robert K. Massie, Dreadnought: Britain, Germany, and the Coming of the Great War (New York: Random House

Publishing Group, 1991).

3. Franz-Stefan Gady, ‘Dreadnought 2050: Is this the Battleship of the Future?’, The Diplomat, 07/09/2015,

https://bit.ly/45iFgJL.

4. Patrick Tucker, ‘A “ChatGPT” For Satellite Photos Already Exists’, Defense One, 17/04/2023, https://bit.ly/3IqtGTa.

5. Kyle Cragge, ‘Every Ship a SAG and the LUSV Imperative,’ CIMSEC, 02/03/2023, https://bit.ly/3Mpb32X.

6. Dmitry Filipoff, ‘Fighting DMO, Pt. 1: Defining Distributed Maritime Operations and the Future of Naval Warfare’, CIMSEC, 20/02/2023, https://bit.ly/42Vj0Ea.

7. Robert K. Massie, Dreadnought: Britain, Germany, and the Coming of the Great War (New York: Random House Publishing Group, 1991).

Featured Image: ATLANTIC OCEAN (Sept. 23, 2019) Royal navy aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth (R08) transits the Atlantic Ocean, Sept. 23. (Photo courtesy of HNLMS De Ruyter)

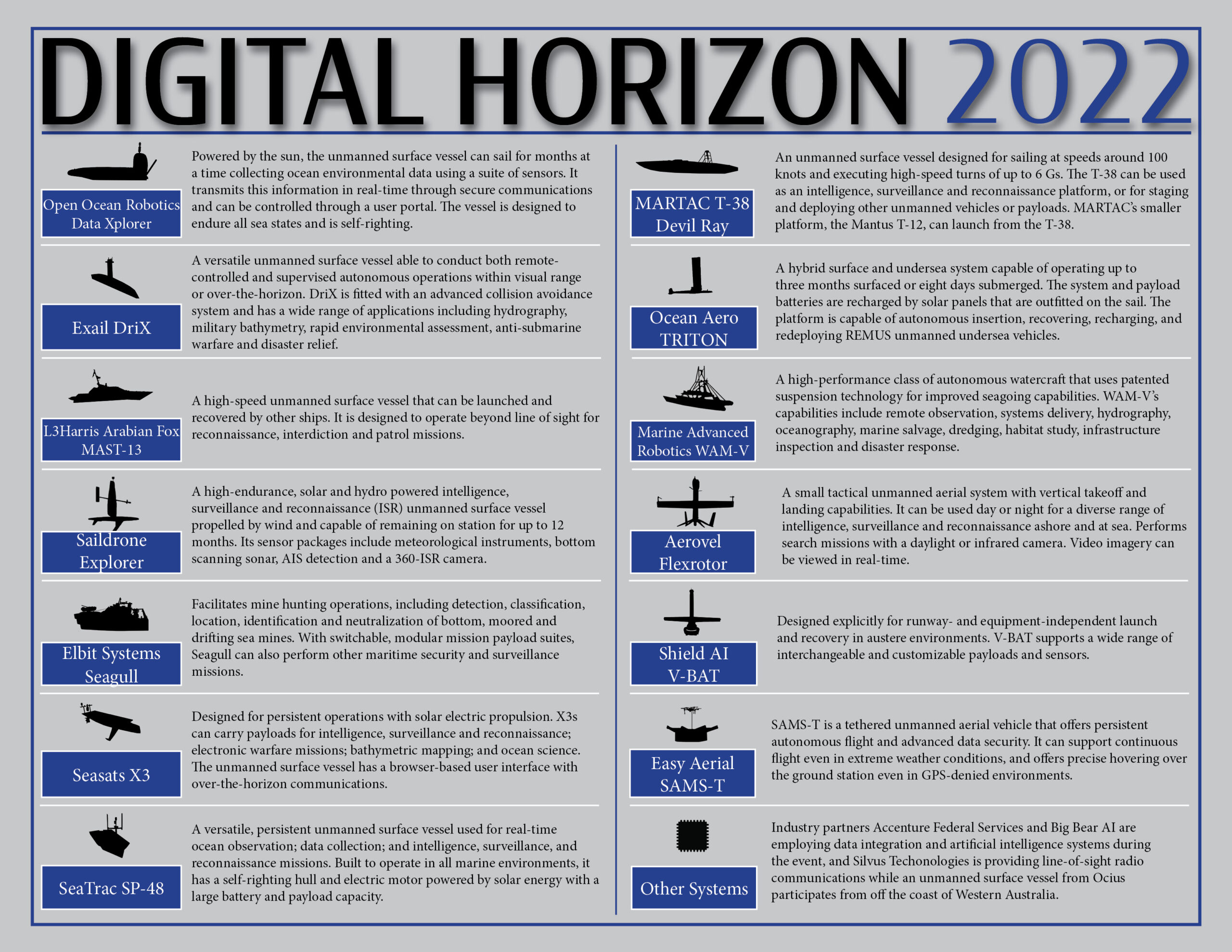

MANAMA, Bahrain (Nov. 19, 2022) Various unmanned systems sit on display in Manama, Bahrain, prior to exercise Digital Horizon 2022. (U.S. Army photo by Sgt. Brandon Murphy)

MANAMA, Bahrain (Nov. 19, 2022) Various unmanned systems sit on display in Manama, Bahrain, prior to exercise Digital Horizon 2022. (U.S. Army photo by Sgt. Brandon Murphy) A Marine Advanced Robotics WAM-V unmanned surface vessel operates in the Arabian Gulf, Nov. 29, during Digital Horizon 2022. (U.S. Army photo by Sgt. Brandon Murphy)

A Marine Advanced Robotics WAM-V unmanned surface vessel operates in the Arabian Gulf, Nov. 29, during Digital Horizon 2022. (U.S. Army photo by Sgt. Brandon Murphy)