#FIGHTFOR15

USA

Case for $15 minimum federal wage convincing

The New York Times Editorial

This editorial first appeared in The New York Times.

Guest editorials don’t necessarily reflect the Denton Record-Chronicle’s opinions.

Opponents of minimum-wage laws have long argued that companies have only so much money and, if required to pay higher wages, they will employ fewer workers.

Now there is evidence that such concerns, never entirely sincere, are greatly overstated.

Over the past five years, a wave of increases in state and local minimum-wage standards has pushed the average effective minimum wage in the United States to the highest level on record. The average worker must be paid at least $11.80 an hour — more after inflation than the last peak, in the 1960s, according to an analysis by the economist Ernie Tedeschi.

And even as wages have marched upward, job growth remains strong. The unemployment rate at the end of 2019 will be lower than the previous year for the 10th straight year.

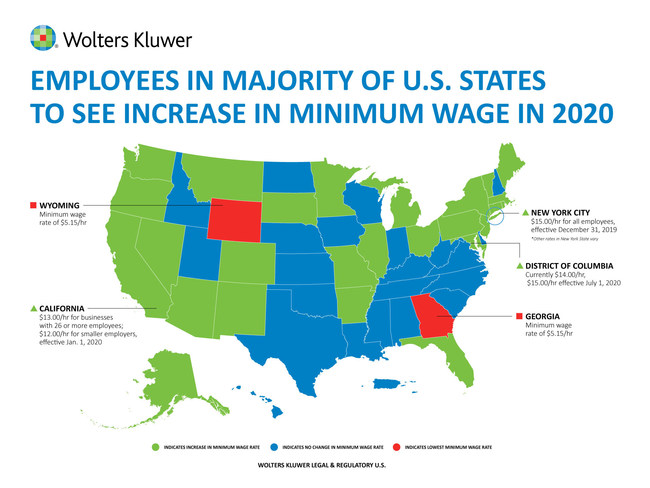

The interventions by some state and local governments, however, do not obviate the need for federal action. To the contrary. Millions of workers are being left behind because 21 states still use the federal standard, $7.25 an hour, which has not risen since 2009 — the longest period without an increase since the introduction of a federal standard in the 1930s.

Across much of America, the minimum wage is set to rise again in the next few days. In Maine and Colorado it will reach $12; in Washington, $13.50; in New York City, $15. Workers in the rest of the country also deserve a raise. The time has come to increase the federal minimum.

House Democrats passed legislation in July that would gradually increase the federal standard to $15 an hour in 2025 — likely raising the real value above the peak value in the late 1960s — and most of the Democrats running for president have endorsed the legislation. Last year, only about 430,000 people — or 0.5% of hourly workers — were paid the federal minimum. The share has fallen in recent years as state and local governments, and some employers, have stepped in. But a much larger group of workers stand to benefit, because they now earn less than the proposed minimum. The Congressional Budget Office estimated a $15 minimum hourly wage would raise the pay of at least 17 million workers.

Among the beneficiaries: people who work for tips. Federal law lets businesses pay $2.13 an hour to waiters, bartenders and others who get tips, so long as the total of tips and wages meets the federal minimum. The legislation would end that rule; the same minimum would apply to all hourly employees. Opponents of the change argue customers will curtail tipping and workers will end up with less money. But eight states, including Minnesota, Montana and Oregon, already have a universal minimum, including for tipped workers, and restaurant workers in those states make more money.

Crucially, the legislation also would require automatic adjustments in the minimum wage to keep pace with wage growth in the broader economy. The current minimum rises only when Congress is in the mood. As a result, the purchasing power of the federal minimum wage has eroded by nearly 40% over the past half-century. A full-time worker making the minimum wage cannot afford a one-bedroom apartment in almost any American city.

The simplistic view that minimum-wage laws cause unemployment commanded such a broad consensus in the 1980s that this editorial board came out against the federal minimum in 1987, calling it “an idea whose time has passed,” and citing as evidence “a virtual consensus among economists.” The old critique is still put forward regularly by the restaurant industry and other major employers of low-wage workers.

But evidence that any such effects are relatively small has been piling up for several decades. A groundbreaking study published in 1993 by the economists David Card and Alan Krueger examined a minimum-wage rise in New Jersey by comparing fast-food restaurants there and in an adjacent part of Pennsylvania. It found no impact on employment.

This prompted other economists to test the standard theory. This year, the British government asked the economist Arindrajit Dube to review the results accumulated over the last quarter-century. Mr. Dube reported the sum total of the research showed minimum-wage increases raised compensation while producing a “very muted effect” on employment.

The patchwork nature of recent minimum-wage increases — the rate rising in some jurisdictions while staying the same in adjacent areas — is offering new opportunities for research.

For most companies, the bill is relatively small, and it can be defrayed by giving less money to shareholders, or by raising prices. Opponents often argue minimum-wage increases will encourage automation, but the point is easily overstated. Companies constantly invest in technology: McDonald’s is installing self-order kiosks across the United States, not just at places with higher minimum wages. And instead of replacing workers with robots, companies may choose to invest in technology that enhances the productivity of their workforce.

More than doubling the current federal standard would be a significant change, and it is not without risk. It is possible that a national $15 standard would produce the kinds of damage critics have long predicted; the Congressional Budget Office puts the potential increase in unemployment somewhere between zero and 3.7 million people, essentially acknowledging the effects are unpredictable.

One simple corrective, proposed by Senator Michael Bennet of Colorado, would be to include exemptions from the $15 standard for low-wage metropolitan areas and rural areas.

But the successful increases in minimum-wage standards across a diverse range of states and cities suggest the broader risk is worth taking. The American economy is generating plenty of jobs; the problem is in the paychecks. The solution is a $15 federal minimum wage.

---30---

Employees in majority of U.S. states to see increase in minimum wage in 2020. (Credit: Wolters Kluwer Legal & Regulatory U.S.)

Employees in majority of U.S. states to see increase in minimum wage in 2020. (Credit: Wolters Kluwer Legal & Regulatory U.S.)

CBS NEWS

CBS NEWS CBS NEWS

CBS NEWS