The degree to which the world depends on oil and gas is not well understood

Publishing date:Dec 14, 2021 •

To appreciate the complexities of the competing demands between climate action and the continued need for energy, consider the story of an award — one that the recipient very much did not want and, indeed, did not bother to pick up.

It began when Innovex Downhole Solutions, a Texas-based company that provides technical services to the oil and gas industry, ordered 400 jackets from North Face with its corporate logo.

But the iconic outdoor-clothing company refused to fulfill the order. North Face describes itself as a “politically aware” brand that will not share its logo with companies that are in “tobacco, sex (including gentlemen’s clubs) and pornography.”

And as far as North Face is concerned, the oil and gas industry fell into that same category — providing jackets to a company in that industry would go against its values. Such a sale would, it said, be counter to its “goals and commitments surrounding sustainability and environmental protection,” which includes a plan to use increasing amounts of recycled and renewable materials in its garments in future years.

But, as it turns out, North Face’s business depends not only on people who like the outdoors, but also on oil and gas: At least 90 percent of the materials in its jackets are made from petrochemicals derived from oil and natural gas. Moreover, many of its jackets and the materials that go into them are made in countries such as China, Vietnam, and Bangladesh, and then shipped to the United States in vessels that are powered by oil. To muddy matters further, not long before North Face rejected the request, its corporate owner had built a new hangar at a Denver airport for its corporate jets, all of which run on jet fuel.

To spotlight the obvious contradiction, the Colorado Oil and Gas Association presented its first ever Customer Appreciation Award to North Face for being “an extraordinary oil and gas customer.” That’s the award North Face spurned.

Different people will draw different conclusions from this episode. Central to the response to climate change is the transition from carbon fuels to renewables and hydrogen, augmented by carbon capture. This was highlighted at the historic COP26 climate conference in Glasgow, Scotland, which emphasized the need for urgency and a greater ambition on climate backed by a host of significant initiatives, including carbon markets, and country pledges of carbon neutrality by 2050 or a decade or two thereafter. The North Face story, however, offers a difficult reminder that the energy transition is a whole lot more complicated than may be recognized.

As if to remind us of the complexities, a most unwelcome guest appeared on the doorstep of the Glasgow conference: an energy crisis that has gripped Europe and Asia. Energy crises traditionally begin with oil, but this recent one has been driven by shortages of coal and liquefied natural gas (LNG). That sent prices spiking, disrupting electricity supplies in China, which then led to the rationing of electricity there, the closing of factories, and further disruptions of the supply chains that send goods to America.

In Europe, the energy shortages were made worse by low wind speeds in the North Sea, which for a time drastically reduced the electricity produced by offshore wind turbines for Britain and Northern Europe. Gas, coal, and power prices shot up — as much as seven times in the case of LNG. Factories, unable to afford the suddenly high energy costs, stopped production, among them plants in Britain and Europe making fertilizers needed for next spring’s agricultural season.

Trailing the other fuels, oil prices reached the US$80 range. With a tightening balance between supply and demand, some were warning that oil could exceed US$100 a barrel. Gasoline prices have hit levels in the United States that alarm politicians, who know that such increases are bad for incumbents. That — along with worsening inflation — is why the Biden administration asked Saudi Arabia and Russia to put more oil into the market, so far to no avail. The administration then announced, on the eve of Thanksgiving, the largest-ever release of oil from the U.S. government’s strategic petroleum reserve, in coordination with other countries, to temper prices.

Energy shock

Is this energy shock a one-off resulting from a unique conjunction of circumstances? Or is it the first of what will be several crises resulting from straining too hard to bring 2050 carbon-reduction goals rapidly forward — potentially prematurely choking off investment in hydrocarbons, thus triggering future shocks? If it’s a onetime event, then the world will move on in a few months. But if it is followed by further energy shortages, governments could be forced to rethink the timing and approach to their climate goals. The current shock offered just such an example: Although Britain is calling for an end to coal, it was nevertheless forced to restart a mothballed coal-powered plant to help make up for the electricity shortage.

Jean Pisani-Ferry, a French economist and sometime adviser to French President Emmanuel Macron, is among the most prominent voices pointing to the consequences that could result from trying to move too fast. In August, before the current energy crisis began, he warned that going into overdrive on transitioning away from fossil fuels would lead to major economic shocks similar to the oil crises that rocked the global economy in the 1970s. “Policymakers,” he wrote, “should get ready for tough choices.”

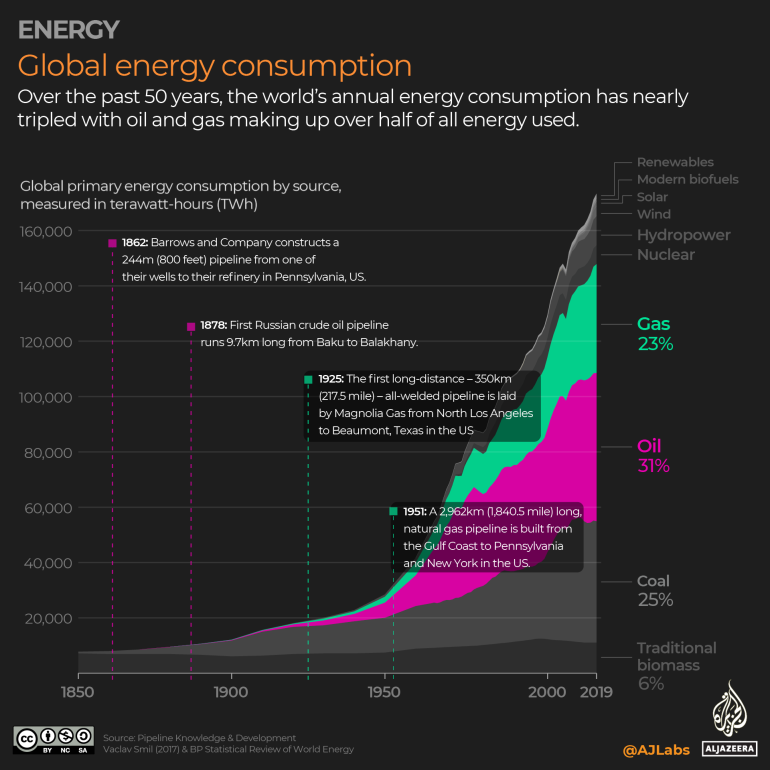

The term energy transition somehow sounds like it is a well-lubricated slide from one reality to another. In fact, it will be far more complex: Throughout history, energy transitions have been difficult, and this one is even more challenging than any previous shift. In my book The New Map, I peg the beginning of the first energy transition to January 1709, when an English metalworker named Abraham Darby figured out that he could make better iron by using coal rather than wood for heat. But that first transition was hardly swift. The 19th century is known as the “century of coal,” but, as the technology scholar Vaclav Smil has noted, not until the beginning of the 20th century did coal actually overtake wood as the world’s No. 1 energy source. Moreover, past energy transitions have also been “energy additions”—one source atop another. Oil, discovered in 1859, did not surpass coal as the world’s primary energy source until the 1960s, yet today the world uses almost three times as much coal as it did in the ’60s.

The coming energy transition is meant to be totally different. Rather than an energy addition, it is supposed to be an almost complete switch from the energy basis of today’s $86 trillion world economy, which gets 80 percent of its energy from hydrocarbons. In its place is intended to be a net-carbon-free energy system, albeit one with carbon capture, for what could be a $185 trillion economy in 2050. To do that in less than 30 years — and accomplish much of the change in the next nine — is a very tall order.

Here is where the complexities become clear. Beyond outerwear, the degree to which the world depends on oil and gas is often not understood. It’s not just a matter of shifting from gasoline-powered cars to electric ones, which themselves, by the way, are about 20 percent plastic. It’s about shifting away from all the other ways we use plastics and other oil and gas derivatives. Plastics are used in wind towers and solar panels, and oil is necessary to lubricate wind turbines. The casing of your cellphone is plastic, and the frames of your glasses likely are too, as well as many of the tools in a hospital operating room. The air frames of the Boeing 787, Airbus A350, and F-35 Joint Strike Fighter jet are all made out of high-strength, petroleum-derived carbon fibre. The number of passenger planes is expected to double in the next two decades. They are also unlikely to fly on batteries.

Oil products have been crucial for dealing with the pandemic too, from protective gear for emergency staff to the lipids that are part of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines. Have a headache? Acetaminophen—including such brands as Tylenol and Panadol—is a petroleum-derived product. In other words, oil and natural-gas products are deeply embedded throughout modern life.

Existential question

There’s another complexity beyond the technical challenge. Call it a new “North–South divide.” The original divide emerged as an economic struggle in the 1970s between the developed countries of the Northern Hemisphere and the developing countries (and former colonies) of the Southern Hemisphere. That was the decade when OPEC burst onto the global scene, with the price of oil very much at the centre of the battle. The rancor of that divide was reduced over time with the advance of globalization, the rise of emerging markets, and increased economic integration.

A different divide is beginning to develop today around differing perspectives on how to tackle climate change. It once again pits the developed world against developing countries, but the contours are different. For the developed world, as Glasgow demonstrated, climate is an overwhelming imperative — often described by political leaders as the “existential” question. While also deeply concerned about climate, developing countries face other existential questions as well. In addition to climate, they struggle with recovering from COVID-19, reducing poverty, promoting economic growth, improving health, and maintaining social stability.

For India, it’s a question of “energy transitions” — plural — which reflects the fact that its per capita income is only one-tenth that of the United States. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government has announced very ambitious goals for wind, solar, and hydrogen, and has set a net-zero target for 2070. Yet at the same time, it has said it will continue to use hydrocarbons to achieve its immediate priorities. As the government put it in an official report, “Energy is the mainstay of the development process of any country.”

Mixing all exploitable energy resources is the only feasible way forward in our contextDHARMENDRA PRADHAN

“Our energy requirements are vast and robust. Mixing all exploitable energy resources is the only feasible way forward in our context,” Dharmendra Pradhan, until recently the minister of petroleum and natural gas and now the minister of education, told me. “India will pursue the energy transition in our own way.”

So while the European Union debates whether natural gas has any appropriate role in its own future energy program, India is building a US$60 billion natural-gas infrastructure system to reduce its reliance on coal, thereby reducing stifling pollution for its urban population and bringing down carbon-dioxide emissions. It is also delivering propane to villagers so that they don’t have to cook with wood and waste any longer, and suffer resulting illnesses and premature death from indoor air pollution.

A similar point was made by Nigeria’s vice president, Yemi Osinbajo, when I spoke with him this year. “The term energy transition itself is a curious one,” he began. “We sometimes tend to focus on one element of the transition. But in fact, that energy transition itself is multidimensional” and must take “into account the different realities of various economies and accommodat[e] various pathways to net zero.”

Osinbajo is particularly worried about European banks and international financial institutions “banning” the financing of hydrocarbon development, especially natural gas, owing to climate concerns. “Limiting the development of gas projects poses big challenges for African nations, while they would make an insignificant dent in global emissions,” he said. Natural gas and natural gas liquids, he continued, are “already replacing the huge amounts of charcoal and kerosene cookstoves that are most widely used for cooking, and thus saving millions of lives otherwise lost to indoor air pollution annually.”

Aissatou Sophie Gladima, the energy minister of Senegal, put it more pithily: Restricting lending for oil and gas development, she said, “is like removing the ladder and asking us to jump or fly.”

Moreover, a number of energy-producing developing countries depend on exports of oil and gas for their budgets and social spending. It is not obvious what would replace those revenues. In October, a top U.S. government official warned American companies of “regulatory actions” and other potential penalties if they made new investments in African oil and gas resources. Yet there’s no ready alternative for Nigeria, with a population of more than 200 million and a per capita income that’s one-12th of the United States’, and which depends on oil and gas exports for 70 percent of its budget and 40 percent of its GDP.

“Africa did not cause climate change, and its role in emissions is very small,” says Hakeem Belo-Osagie, a senior lecturer at Harvard Business School focusing on the business and economy of Africa. “Covid has wrecked [the] finances of many African countries, and African countries cannot be expected to cut fossil-fuel production, as it is essential to the finances of several African countries.”

Will a new North–South divide lead to a fracturing in global policies? For an early indicator, look at what happens in the next two years on global trade. The growth of trade and the opportunities it presented to developing countries have done much to ease the original divide. But signs of the new tensions are certainly there.

Europe is moving to establish a “carbon border adjustment mechanism,” which is a complicated name for what is essentially a carbon tariff. It will be assessed according to “carbon intensity” — that is, the amount of carbon expended in making a product. Europe sees these tariffs as a way to ensure that its policies and values on climate change are adopted globally, while providing protection to European industries that face higher costs because of carbon pricing. The EU is starting with tariffs on a limited number of goods but is expected to expand the list. The Biden administration is also mulling carbon tariffs. Yet developing countries regard the moves as discriminatory and an effort to impose Europe’s policies on them.

The 2015 Paris climate conference established the “what” — the goal of carbon neutrality. COP26 in Glasgow resulted in major steps forward on the “how” — achieving the goal. But when it comes to the energy transition itself, we may still have much to learn about the complexities that lie ahead.

Daniel Yergin, vice chairman of IHS Markit, is a Pulitzer Prize winning author. His latest book is “The New Map: Energy, Climate, and the Clash of Nations.”

Copyright: Daniel Yergin. Originally published by The Atlantic.

.png)