Exporting the U.S. Shale Boom Has Changed Oil Markets Forever

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Five years ago on New Year’s Eve, the Theo T left the Texas Gulf Coast with the first U.S. shale crude shipment overseas. The oil, gathered from nearby ConocoPhillips wells and sold to trading giant Vitol Group, set sail for Italy just two weeks after lawmakers lifted a long-standing ban on exports.It was the start of a trade that would reshape global oil markets, shift geopolitical power and upend entire economies. The shale boom itself has turned the U.S. into the world's largest oil producer and has moved it ever closer to a long-cherished dream of ending dependence on Middle East oil. But the export boom created an entirely new market, sending crude pulled from the shale fields of Texas, New Mexico and North Dakota to more than 50 countries, with shipments often surpassing those of any OPEC nation aside from Saudi Arabia.

These past five years could very well go down as the best years that U.S. shale oil exporters will ever see. Covid-19 has obliterated global fuel demand and bankrupted more than 40 drillers across America. Exactly how much oil leaves U.S. shores in the coming years will largely depend on how quickly the world can recover from the pandemic and how aggressively politicians work to shift the world away from fossil fuels. But the global reach of U.S. shale has changed oil markets for good and remains a potent, diplomatic weapon for the U.S.“Opening the shale revolution to the world through the export ban lifting helped shift the global oil market psychology from supply scarcity to abundance,” said Karim Fawaz, IHS Markit's director of energy research analysis. “It unshackled the U.S. industry to keep growing past its domestic refining limitations.”

Perhaps no two groups have gained from the export of America's shale boom more than producers of U.S. oil and the giant commodities merchants who trade it. Wildcatters including billionaire Harold Hamm of Continental Resources Inc. and Scott Sheffield of Pioneer Natural Resources Co. saw their revenues more than double as exports took off. “Today the U.S. has its own petrodollars,” Hamm said in August 2018 as U.S. oil shipments overseas boomed.

Trading giants including Trafigura Group, Vitol, Gunvor Group and Mercuria Energy Group profited from buying cheaper shale oil, shuttling it to the U.S. coast and shipping it to eager buyers in Europe and Asia. Betting that shipments would surge, they expanded their trading desks in the U.S., invested in ports, pipelines and export facilities. By the last week of 2019, exports of American oil had reached nearly 4.5 million barrels a day.

U.S. shale's gain was OPEC's loss. As shale oil flooded the market, OPEC was forced to cede market share. The U.S., which had been one of OPEC's biggest customers, has cut its monthly imports by about 50% since mid-2006. Last week, Saudi Arabian cargoes to the U.S. fell to zero for the first time since at least 2010.Exports have turned U.S. shale into a permanent thorn in OPEC's side. The oil cartel has had to join forces with Russia, Mexico and other major producers to ratchet back production several times in the past five years while U.S. shale expanded its reach into key markets.

Shale now shares the fortunes — and the misfortunes — of being a major exporter. The strongest evidence of this yet came in March when U.S. President Donald Trump joined leaders of the world's largest oil-producing nations to hammer out an unprecedented accord to save oil markets from total collapse as the pandemic slashed demand.

The U.S.’s shrinking dependence on foreign imports has also allowed the Trump administration to impose increasingly debilitating sanctions on two OPEC founding members — Venezuela and Iran — without fear of higher fuel prices back home. And with American shale now readily available in global markets, oil price spikes tied to conflicts in the Middle East are shorter and more subdued.

“The flow of U.S. oil since the ban's end has kept global oil supply in balance even at times when politics have caused the loss of supply from Iran, Venezuela and Libya,” said Sandy Fielden, director of oil research at Morningstar Inc.

How long the U.S. can maintain this clout on global oil markets remains to be seen.

One bullish sign for U.S. oil exports: China’s appetite for crude has come back with a vengeance since the country emerged from lockdowns. That has helped draw down American oil inventories as U.S. cargoes start hitting the water once again, reaching 3.6 million barrels a day in the week of Christmas.

There is no other country that will dictate the fate of U.S. oil exports more than China. About two years after U.S. lawmakers lifted the export ban, shipments to China reached 2 million barrels a day, making it by far the largest buyer of American oil. The Asian nation's appetite for crude has rebounded since it emerged from lockdowns, but Saudi Arabia and Russia remain major suppliers to the country and competition may heat up later this year as OPEC+ restores output.“The Asian market will become more competitive as OPEC+ restores some of its production,” said Shirin Lakhani, a senior oil analyst at Rapidan Energy Group. “For OPEC+ producers, sales into Asia have the best profit margins due to proximity and logistics.”

Demand for U.S. barrels will also depend on how well the global economy fares in the coming years after its deepest recession since World War II. The World Bank forecasts a 4% economic rebound this year, following a 4.3% contraction in 2020, but cautioned there’s an “exceptional level of uncertainty” as the pandemic may reduce potential global growth for a decade. It will take until the end of 2021 for the oil glut left behind by the pandemic to clear as demand will be “lower for longer than expected” when the virus emerged in the spring, the International Energy Agency said in December.

The incoming Biden administration and its plan to completely reshape U.S. energy policy will undoubtedly affect U.S. oil exports. Among the president-elect’s promises on the campaign trail were stronger regulation of the hydraulic fracturing that unleashed the U.S. shale boom, a ban on fracking federal lands and a broader transition away from fossil fuels. Depending on how it's executed, the ban alone may not significantly affect U.S. oil shipments. It would theoretically only apply to new drilling licenses and affect a fairly limited amount of new oil output, namely in New Mexico.

But that may only prove to be a temporary boon for oil exporters. Joe Biden is among a growing chorus of world leaders pledging to wean their nations off fossil fuels for good. More than 120 countries, including China, the U.K. and Canada, have committed to achieving net-zero emissions over the course of the next three decades. The president-elect himself has pledged to achieve net-zero emissions in the U.S. no later than 2050. Electric transportation lies at the center of virtually every country's plan to go carbon-neutral.

Annual sales of electric cars around the world — including trucks and buses — reached almost 27 million in 2019 and are set to accelerate in the coming years to a rate of 133 million vehicles a year in the next two decades, according to BloombergNEF estimates. By 2040, around 500 million passenger electric vehicles will be on the road, or roughly one third of the world’s total.But as long as the world moves mostly on fossil fuels, shale will continue to fight for its share of the global market. “The lifting of the export ban and the incredible growth and resilience in domestic shale will keep the U.S. a crucial exporter of American crude oil for the foreseeable future,’’ Lakhani said.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.

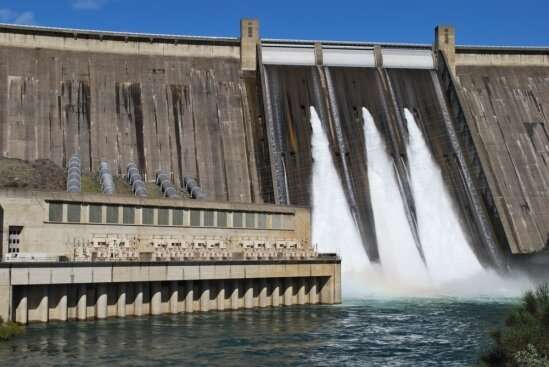

The climate crisis has severely impacted California’s water-energy nexus. Here we see the contrast between a full reservoir behind Folsom Dam in July 2011 compared to the water level under the extreme drought in January 2014. Credit: United States Bureau Of Reclamation

The climate crisis has severely impacted California’s water-energy nexus. Here we see the contrast between a full reservoir behind Folsom Dam in July 2011 compared to the water level under the extreme drought in January 2014. Credit: United States Bureau Of Reclamation