VICTOR JARA THOU ART AVENGED

Ex-Chilean military officer suspected of killing famed singer 50 years ago nabbed in Florida

SYRA ORTIZ BLANES AND OMAR RODRÍGUEZ ORTIZ

MIAMI HERALD • October 16, 2023

Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) Tampa’s Space Coast office and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) Miami’s Orlando suboffice arrested Pedro Paulo Barrientos Nunez during a traffic stop in Deltona, Fla., on Oct. 5, 2023. (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement/TNS)

MIAMI (Tribune News Service) — In one of the last songs Chilean folk singer Víctor Jara ever recorded over 50 years ago, he transformed the ominous verses of one of his homeland’s greatest poets into a ballad of stubborn and hopeful nation-building.

“I do not want the country divided, or bled out by seven knives, I want Chile’s light raised over the new house built,” he sings in “Aquí me quedo,” (Here I stay), blending the words of Pablo Neruda with the thrum of guitars.

Jara never finished what would become his final album. In September 1973, he was tortured and killed during a military coup that brought General Augusto Pinochet to power in the South American nation.

Jara’s wife and children have fought for half a century to hold accountable those responsible. But it wasn’t until earlier this month that Immigration and Customs Enforcement announced authorities had arrested Pedro Barrientos Núñez, an ex-Chilean Armed Forces lieutenant suspected of executing Jara, during a traffic stop in Volusia County, Fla., on Oct. 5.

“Barrientos will now have to answer the charges he’s faced with in Chile for his involvement in torture and extrajudicial killing of Chilean citizens,” said Homeland Security Investigations Tampa Special Agent in Charge John Condon.

A Chilean court formally accused him of murdering Jara in December 2012. The country’s Supreme Court ordered Barrientos Núñez’s extradition in Jan. 2013. He had relocated to the United States in 1990 on a visitor visa and later became a U.S. citizen in 2010, according to court documents.

Chile’s government has known for years that the ex-lieutenant was in the United States. But his arrest, over a decade after his indictment, puts a spotlight on the challenges the country has faced in bringing to justice the government officials who committed atrocities during Pinochet’s 17-year rule.

Valentina Infante Batiste, a Chilean sociologist who studies how countries remember and respond in the aftermath of human rights violations and dictatorships, told the Miami Herald that it wasn’t until after 1998, when Pinochet was first detained in London at the request of Spanish authorities, “that the engine of justice accelerated.” He died in 2006 without ever going to prison. Jara’s widow first opened a criminal investigation in 1978.

“Justice in Chile has taken a long time,” said Infante Batiste.

Chile’s Foreign Affairs Minister, Alberto van Klaveren said in a recent interview with Chilean radio station Radio Pauta that American and Chilean authorities had been in conversations about Barrientos Núñez for a long time, but kept it under wraps because he was “on the run” and authorities didn’t want him to know they were looking for him.

Barrientos Núñez is currently being held in an ICE facility in Baker County. Van Klaveren said they were waiting for him to be deported. Extraditions from the U.S. are generally a two-part process where a federal court determines if the other country’s request meets the necessary requirements. Then, the State Department secretary determines whether to hand the person over or not. Extraditions can take years and be subject to appeals.

A spokesperson for Chile’s Supreme Court told the Miami Herald that despite the 2012 criminal indictment in Chile, the criminal process had not moved forward because he was in the United States.

“In Chile, people cannot be tried while not physically present ... once he is expelled from the United States, the criminal process against him will have to be resumed,” said the spokesperson over email.

A family’s day in court

Last month, the U.S. Department of State called the 50th anniversary of the military coup in Chile — which resulted in democratically-elected president Salvador Allende taking his life and Pinochet’s rise to power — an “opportunity to reflect on this break in Chile’s democratic order and the suffering that it caused.”

The American government secretly spent millions to weaken Allende and Chile’s left in the ’60s and ’70s. The CIA revealed in declassified documents that it had tried to launch a separate coup right after Allende’s victory. The agency said it didn’t help with the 1973 coup. But it acknowledged in the records knowing about the plan, being in contact with some of its masterminds for intelligence collection, not discouraging the takeover, and “actively” backing the military junta after the ousting.

Over 3,000 people were killed, disappeared and executed for political reasons during Pinochet’s repressive government, according to Chilean government estimates. Tens of thousands more were detained, persecuted and tortured.

SYRA ORTIZ BLANES AND OMAR RODRÍGUEZ ORTIZ

MIAMI HERALD • October 16, 2023

Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) Tampa’s Space Coast office and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) Miami’s Orlando suboffice arrested Pedro Paulo Barrientos Nunez during a traffic stop in Deltona, Fla., on Oct. 5, 2023. (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement/TNS)

MIAMI (Tribune News Service) — In one of the last songs Chilean folk singer Víctor Jara ever recorded over 50 years ago, he transformed the ominous verses of one of his homeland’s greatest poets into a ballad of stubborn and hopeful nation-building.

“I do not want the country divided, or bled out by seven knives, I want Chile’s light raised over the new house built,” he sings in “Aquí me quedo,” (Here I stay), blending the words of Pablo Neruda with the thrum of guitars.

Jara never finished what would become his final album. In September 1973, he was tortured and killed during a military coup that brought General Augusto Pinochet to power in the South American nation.

Jara’s wife and children have fought for half a century to hold accountable those responsible. But it wasn’t until earlier this month that Immigration and Customs Enforcement announced authorities had arrested Pedro Barrientos Núñez, an ex-Chilean Armed Forces lieutenant suspected of executing Jara, during a traffic stop in Volusia County, Fla., on Oct. 5.

“Barrientos will now have to answer the charges he’s faced with in Chile for his involvement in torture and extrajudicial killing of Chilean citizens,” said Homeland Security Investigations Tampa Special Agent in Charge John Condon.

A Chilean court formally accused him of murdering Jara in December 2012. The country’s Supreme Court ordered Barrientos Núñez’s extradition in Jan. 2013. He had relocated to the United States in 1990 on a visitor visa and later became a U.S. citizen in 2010, according to court documents.

Chile’s government has known for years that the ex-lieutenant was in the United States. But his arrest, over a decade after his indictment, puts a spotlight on the challenges the country has faced in bringing to justice the government officials who committed atrocities during Pinochet’s 17-year rule.

Valentina Infante Batiste, a Chilean sociologist who studies how countries remember and respond in the aftermath of human rights violations and dictatorships, told the Miami Herald that it wasn’t until after 1998, when Pinochet was first detained in London at the request of Spanish authorities, “that the engine of justice accelerated.” He died in 2006 without ever going to prison. Jara’s widow first opened a criminal investigation in 1978.

“Justice in Chile has taken a long time,” said Infante Batiste.

Chile’s Foreign Affairs Minister, Alberto van Klaveren said in a recent interview with Chilean radio station Radio Pauta that American and Chilean authorities had been in conversations about Barrientos Núñez for a long time, but kept it under wraps because he was “on the run” and authorities didn’t want him to know they were looking for him.

Barrientos Núñez is currently being held in an ICE facility in Baker County. Van Klaveren said they were waiting for him to be deported. Extraditions from the U.S. are generally a two-part process where a federal court determines if the other country’s request meets the necessary requirements. Then, the State Department secretary determines whether to hand the person over or not. Extraditions can take years and be subject to appeals.

A spokesperson for Chile’s Supreme Court told the Miami Herald that despite the 2012 criminal indictment in Chile, the criminal process had not moved forward because he was in the United States.

“In Chile, people cannot be tried while not physically present ... once he is expelled from the United States, the criminal process against him will have to be resumed,” said the spokesperson over email.

A family’s day in court

Last month, the U.S. Department of State called the 50th anniversary of the military coup in Chile — which resulted in democratically-elected president Salvador Allende taking his life and Pinochet’s rise to power — an “opportunity to reflect on this break in Chile’s democratic order and the suffering that it caused.”

The American government secretly spent millions to weaken Allende and Chile’s left in the ’60s and ’70s. The CIA revealed in declassified documents that it had tried to launch a separate coup right after Allende’s victory. The agency said it didn’t help with the 1973 coup. But it acknowledged in the records knowing about the plan, being in contact with some of its masterminds for intelligence collection, not discouraging the takeover, and “actively” backing the military junta after the ousting.

Over 3,000 people were killed, disappeared and executed for political reasons during Pinochet’s repressive government, according to Chilean government estimates. Tens of thousands more were detained, persecuted and tortured.

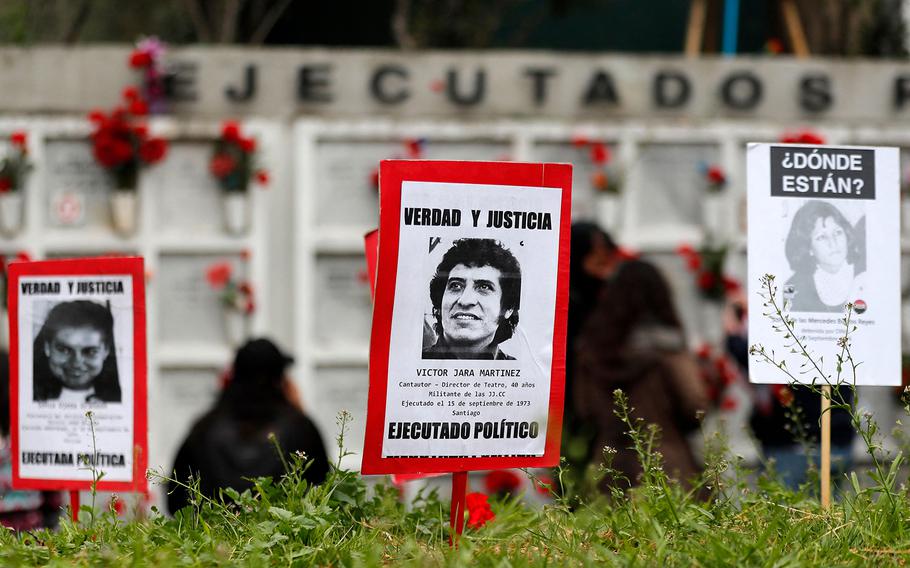

A poster with a picture of teacher and singer Victor Jara, who was tortured and shot to death during the Chilean dictatorship, is seen as people demonstrate at the General Cemetery during the commemoration of the 49th anniversary of the 1973 military coup d’etat of Augusto Pinochet and subsequent death of President Salvador Allende, in Santiago, on Sept. 11, 2022. (Javier Torres, AFP via Getty Images/TNS)

One of those victims was Víctor Lidio Jara Martinez, a well-known communist folk singer-songwriter, playwright, university professor, poet, and Allende ally. Jara was a leading member of the leftist Nueva canción chilena movement that wanted to preserve the country’s folk tradition while advocating for social change through music. He sang about Chile’s poor and indigenous people and wrote lyrical ballads against social inequality, war, and imperialism.

“Already in his time he was tremendously popular and influential, especially for the left,” said Infante Batista.

The military took Jara to a stadium in Santiago in the days after the coup. The sports facility would become a detention and torture camp where thousands were held. Barrientos Núñez was a lieutenant overseeing soldiers there and ordered his underlings to torture and kill Jara, according to a lawsuit that Jara’s wife, children, and estate filed a decade ago against him in a federal court in Florida.

One former member of the Chilean military testified in a separate 2009 case that he had watched Barrientos Núñez shoot the musician and witnessed his torture. Jara was brutally beaten and shot over 40 times in the stadium’s locker room, according to the lawsuit. His wife and daughters buried him in secret before escaping to the United Kingdom.

In 2016, a civil jury ruled in the federal case in Florida that Barrientos Núñez was liable in the killing and torture of Jara. He was ordered to pay $28 million in compensatory and punitive damages. An immigration judge revoked his naturalization and took away his U.S. citizenship this July. That left him with no legal basis to be in the United States.

Barrientos Núñez said in his immigration applications and interviews for permanent residency and citizenship that he had not been involved in military service in another country or participated in the genocide killing of people on the basis of political opinion, according to court records.

In August, Chile’s Supreme Court sentenced six former soldiers to 15 years and a day in prison for killing Jara and lawyer Littré Abraham Quiroga Carvajal, former general director of prisons under Allende. It also handed down a decade-long sentence for kidnapping the pair. Another officer was separately sentenced over five years for covering up the crimes.

‘Pinochet’s legacy is still present’

Barrientos Núñez’s arrest and potential extradition comes five decades after the military coup. It’s been over 30 years since Pinochet lost a referendum vote that led to free elections and a transition back to democracy. Chile has a world-renowned museum of memory that commemorates Pinochet’s victims. The stadium where Jara was held carries his name. But the general’s bloody rule still haunts Chileans.

“Pinochet’s legacy is still present. It’s like an open secret,” said Infante Batiste, the Chilean sociologist.

Allusions to Allende, Pinochet, and the military coup are part of today’s political conversation, said Infante Batiste. When former student activist turned president Gabriel Boric entered the presidential palace for the first time, he turned to greet Allende’s statue. Pinochetistas, enabled by the rise of a populist radical right, hold up photos of the general and his junta at protests — which the scholar said would have once been “absolutely unthinkable.”

Mysteries from the Pinochet years still remain unresolved: Scientists announced this February that the remains of Pablo Neruda, the outspoken communist poet whose words Jara made into song — contained high levels of a botulism strain used to poison political prisoners, raising questions about his demise two weeks after the coup. The experts concluded in 2017 it hadn’t been from prostate cancer, the official cause of death.

But even more pressing to many is where the over 1,000 people who were detained and never seen again might be. Boric launched a plan to search for the missing, which Infante Batiste called an important gesture from the government. It’s historically been on the victim’s relatives to push investigations forward, she said. But Infante Batiste acknowledged the big challenges ahead. The military officers who bore witness and perpetrated the kidnappings and killings share pacts of silence. They are growing old and dying without revealing where the missing are.

The Chileans who haven’t buried loved ones bear the open wounds of a nation once divided.

“Addressing the pain of the families, of the victims, is fundamental,” she said, “As long as their mourning isn’t over, Chile will not achieve peace.”

©2023 Miami Herald.

No comments:

Post a Comment