(Image credit: Alamy)

By Kalpana Sunder16th August 2021

How an auspicious sacred sign was twisted to become the graphic embodiment of hate and intolerance. Kalpana Sunder explores the extraordinary history of a potent emblem.

The equilateral cross with legs bent at right angles – that looks like swirling arms or a pattern of L shapes – has been a holy symbol in Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism for centuries. And, of course, the swastika (or the similar-looking hakenkreuz or hooked cross) is also a symbol of hate, embodying painful and traumatic memories of the Third Reich. The symbol of Nazism, it is associated with genocide and racial hatred after the atrocities of the Holocaust.

More like this:

- The symbol with a secret meaning

- The ancient origins of the new nomads

- A coded symbol hidden in a masterpiece

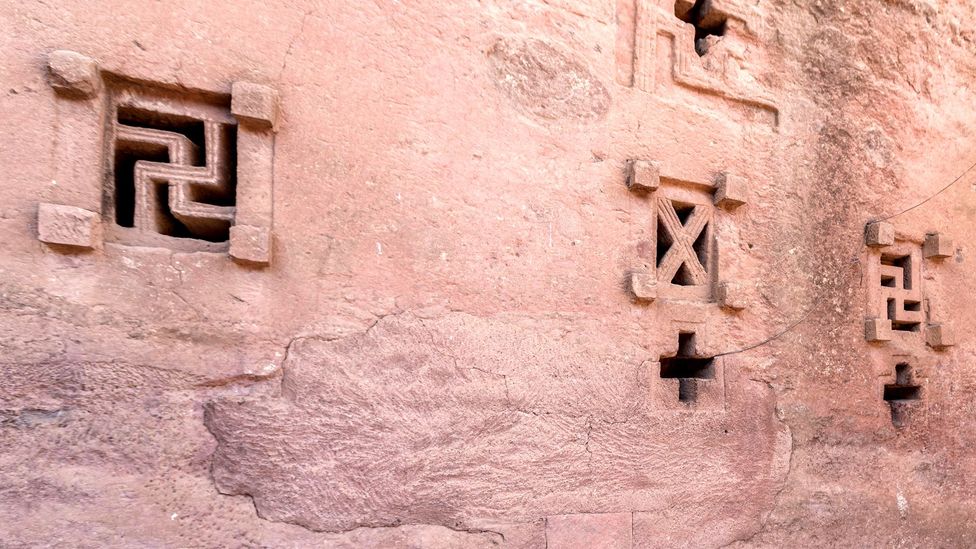

The swastika has a long, complex history – much older than its association with Nazi Germany – dating back to prehistoric times. The emblem was a sign of well-being and long life, and was found everywhere, from the tombs of early Christians to the catacombs of Rome and the Lalibela Rock Churches, to the Cathedral of Cordoba. "The motif appears to have first been used in Eurasia, as early as 7,000 years ago, perhaps representing the movement of the sun through the sky… as a symbol of wellbeing in ancient societies," says the Holocaust Encyclopedia.

The Mezquita Cathedral in Cordoba, Spain, is adorned with intricate symbols including the swastika (Getty Images)

The word swastika comes from the Sanskrit roots su (good) and asti (to prevail), meaning wellbeing, prosperity or good fortune, and has been used in the prayers of the Rig Veda, the oldest of Hindu scriptures. In Hindu philosophy it is said to represent various things that come in fours – the four yugas or cyclical times, the four aims or objectives of life, four stages of life, the four Vedas. Swastika is even a girl's name in certain parts of India.

In Buddhism, known as the manji in Japanese, the emblem signifies the Buddha's footsteps. To Jains it means a spiritual teacher. In India, it's a symbol of the sun god with a clockwise orientation, and the auspicious symbol can be seen, often smeared in turmeric, drawn on thresholds and shop doors as a sign of welcome, or on vehicles, religious scriptures and letterheads. It is displayed at weddings and other festive occasions, to consecrate a new home, and while opening account books at the beginning of the financial year, or starting a new venture.

In Indian philosophy it represents the fourth state of consciousness, which is beyond waking, sleeping and dreaming – Ajay Chaturvedi

Ajay Chaturvedi, author of Lost Wisdom of the Swastika, tells BBC Culture: "The swastika is a four-dimensional cube used in Vedic Mathematics, and also symbolises an entire state of being in Indian philosophy – the fourth state of consciousness, which is beyond waking, sleeping and dreaming. The sign as used by Hitler was demonising [it]… and using it in politics, without any understanding of what it stood for in Indian philosophy, where symbols are always backed by meaning and deep significance."

Windows created in the shape of the swastika on a building in Lalibela, Ethiopia (Credit: Alamy)

Different civilisations associate the sign with outstretched hands, four seasons, four directions or with spreading light in all directions. In the 19th-Century book The Swastika: The Earliest Known Symbol, and Its Migrations, Thomas Wilson documents how the swastika was found all over the ancient world, on everything from quilts and shields to jewellery. Some believe that its shape was inspired by an ancient comet. The Ancient Greeks used swastika motifs to decorate their pots and vases. The ancient Druids and Celts also used the sacred sign, and in Norse mythology the swastika represented Thor's hammer.

The National Museum of the History of Ukraine houses a wide range of objects featuring the symbol. The oldest is probably a mammoth-ivory figurine of a bird, found in 1908, with a meandering swastika pattern on it that was carbon-dated to 15,000 years ago. Seals depicting swastika motifs have been found in the Mohenjo-Daro and Harappan ruins in India.

There are few more potent symbols with alternative meanings than the swastika in its many iterations – Steven Heller

US art director Steven Heller, author of Swastika: Symbol Beyond Redemption? tells BBC Culture: "I am a graphic designer. Symbols and signs and how they are used and manipulated is important to my practice. There are few more potent symbols with alternative meanings than the swastika in its many iterations."

Before World War Two, the swastika was used in branding – seen here at the Carlsberg factory entrance (Credit: Alamy)

In the early 20th Century, the swastika was widely used in Europe as a symbol of good luck. Interlocked swastikas were used in textiles and architecture. "The sign was used in many ways before Hitler adapted it. A sign of good fortune, fertility, happiness, Sun, and it was given spiritual import as well as commercial value when it was used with or as a brand or logo," says Heller. In the early 20th Century, the swastika was used as a symbol of good luck in advertising, architecture and jewellery. The Danish brewing company Carlsberg, headquartered in Copenhagen, used the symbol as its logo from 1881 to the 1930s, and then discontinued it because of its Nazi association.

Until recently, the Finnish Air Force used a swastika as an insignia on its badges. Rudyard Kipling featured the symbol on many of his book covers because of his association with India. It was used as a symbol by the Scouts in Britain until 1935 – like Kipling, Robert Baden Powell may have picked it up in India. For the Navajo people in the US, the right-facing swastika was a symbol of friendship, which they gave up after World War Two.

Hindu cultural organisations and religious groups have tried to explain that the Nazis did not use the swastika, but a hooked cross. The Nazi swastika has the arms turned to 45 degrees giving a slant to the symbol, whereas the swastikas of Hinduism are presented with the base arm lying flat.

A complex history

When Adolf Hitler was looking for a symbol for his newly launched party, he used the hakenkreuz, rotating the swastika to the right and omitting the four dots – he then adopted this as the party's emblem in 1920. Joseph Goebbels, Hitler's minister of propaganda, passed a law in May 1933 that prevented unauthorised commercial use of the hooked cross.

In Hindu tradition, the emblem is frequently used at festive occasions such as weddings

It has been suggested that Hitler's adoption of the symbol may have had its roots in Germans finding similarity between their language and Sanskrit, and drawing a conclusion that Indians and Germans came from the same "pure" Aryan ancestry and lineage. During his extensive excavations, the German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann discovered, in 1871, 1,800 variations of the hooked cross on pottery fragments at the site of ancient Troy, which were similar to artefacts from German history. "This was seen [by the Nazis] as evidence for a racial continuity and proof that the inhabitants of the site had been Aryan all along," writes anthropologist Gwendolyn Leick.

Of course, cultural appropriation usually harms the original culture. The German Orientalist Max Muller wrote to Schliemann, and warned him to avoid using the word swastika on the icons: "Swastika is a word of Indian origin, and has its history and definite meaning in India. I know the temptation is great to transfer names, with which we are familiar, to similar objects which come before us… the occurrence of such crosses in different parts of the world may or may not point to a common origin."

Not everyone agreed with this interpretation, however. In his book The Sign of the Cross: From Golgotha to Genocide, Dr Daniel Rancour-Laferriere, an expert on Christianity, suggests that Hitler's decision to use the hakenkreuz as a symbol of the Nazi party "may have been due to his childhood upbringing at the Benedictine Monastery in Austria, where he repeatedly saw the hooked cross in many places".

In Hinduism the swastika cross has for many centuries been a symbol of religious devotion (Credit: Alamy)

But over the decades, the swastika has become a contentious and controversial cultural icon. In his book The Swastika and Symbols of Hate, Heller says: "The swastika is an ancient symbol that was hijacked and perverted, twisted into the graphic embodiment of intolerance." In many European countries including Germany, public display of Nazi symbols is prohibited by law, and violating such terms is a criminal offence.

New York State Senator Todd Kaminsky introduced a bill in the New York Senate in 2021, which would require schools in the state of New York to teach that the swastika is an example of a hate symbol. Due to the bill's national implications, organisations including the World Hindu Council of America urged the New York Senate to differentiate between the original swastika and the Nazi hakenkreuz.

Director of advocacy and awareness for the World Hindu Council of America (VHPA) Utsav Chakrabarty said, "We acknowledge the horrid way the swastika has been misused and misinterpreted… For the past 70 years, the swastika continues to remain a vilified and maligned symbol. This must be corrected. Instead of censoring the symbol, we must celebrate the positive history of it."

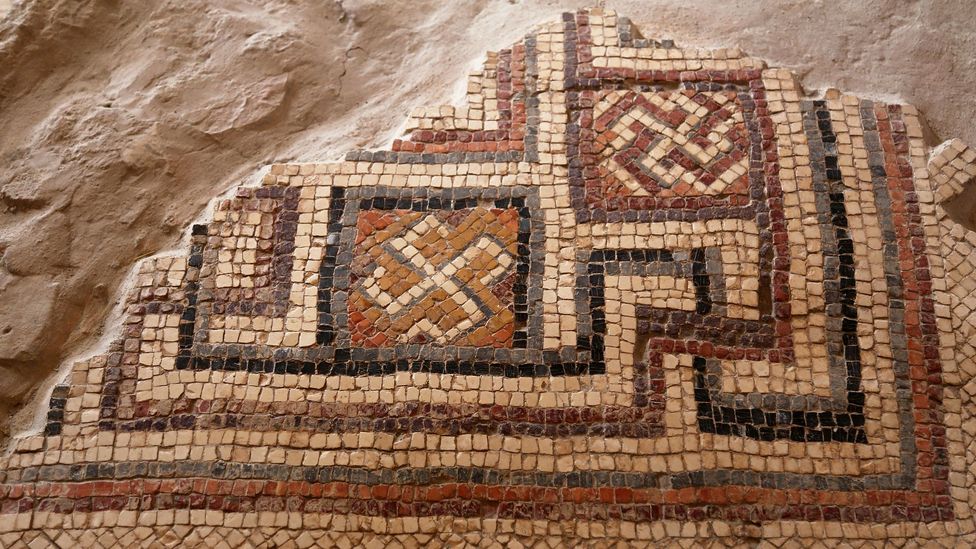

An ancient mosaic in Uzayzy, Jordan, shows a version of the sacred emblem (Credit: Alamy)

Even members of the Jewish community have highlighted on several occasions the way in which the sign has been misused. "A distorted version of this sacred symbol was misappropriated by the Third Reich in Germany, and abused as an emblem under which heinous crimes were perpetrated against humanity, particularly the Jewish people. The participants recognise that this symbol is, and has been, sacred to Hindus for millennia before its misappropriation," said the declaration made at the Second Hindu Jewish Leadership Summit in Jerusalem held in February 2008.

I want to neutralise the swastika, to remove its association with evil, so that no one need fear it anymore – Edith Altman

Swastikas have however been allowed in the filming of historical movies and the making of video games. There have been some attempts to redeem its image by artists down the ages. The symbol was included by pop star Madonna in a video in 2012, accompanying the song Nobody Knows Me. Madonna later said that she used it to show growing intolerance of people to other communities and people.

The KiMo Theatre in New Mexico, USA, is adorned with traditional Navajo emblems (Credit: Alamy)

In 1993, a Jewish artist named Edith Altman – who lost her grandparents to the Holocaust – created an installation entitled Reclaiming the Symbol: The Art of Memory. She painted a gold swastika on a wall above a black Nazi swastika painted on the floor. "I want to neutralise the swastika, to remove its association with evil, so that no one need fear it anymore," she told the Chicago Reader.

The anti-Semitic use of the swastika did not end with World War Two. Even today racist neo-nazi gangs use the sign to desecrate Jewish graves or houses of worship. Some people feel that its taboo status has enhanced its appeal for hate groups. "The latest 2021 police figures from the two cities with the largest Jewish populations, New York and Los Angeles, show both cities tracking for a record year for overall hate crime, with Jews being the most targeted in New York and third most targeted in Los Angeles," says Brian Levin, director of the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism (CSHE), and a professor of criminal justice.

In 2020, a 21-year-old Indian student in the US, Simran Tatuskar, faced a backlash on social media after she attempted to portray the swastika as a peaceful symbol that should be included in the school syllabus. One group tweeted: "In Nazi Germany, one of the first things anti-Semites did was erase the history and persecution of the Jews, minimise their struggles and appropriate their beings. By normalising the swastika, this is repeating that vicious cycle." Ultimately Simran Tatuskar had to clarify her position on the issue, and apologise for any unintentional misunderstanding.

The Shoin Shrine in Hagi, Japan, features the ancient sign (Credit: Getty Images)

Before the 2021 Olympic Games in Japan, the decision to drop the Japanese symbol (the manji) for temples on tourist maps, and replace it with a pagoda icon, provoked a backlash. When the elements of a culture are adopted out of context, it seems, its history and heritage become tainted.

As Brian Levin puts it: "Unfortunately, but rightly, the most recent and widespread use of the swastika as a symbol of Nazi hatred and genocide will forever cast an indelible shadow over its lengthy history and alternative meaning. It is important, however, to note that expanding our teaching of history and civics can incorporate not only the origins of symbols, but how they can be co-opted and rebranded to the most evil of ends."