LONG READ

The executive producer peered at me with concern. It was November 16, 2023 and I had been called into a virtual meeting at CBC. I was approaching my sixth year with the public broadcaster, where I worked as a producer in television and radio.

He said he could tell I was “passionate” about what was happening in Gaza. His job, he told me, was to ensure my passion wasn’t making me biased. He said I hadn’t “crossed the line” yet, but that I had to be careful. The conversation ended with him suggesting that I might want to go on mental health leave.

I declined. My mind was fine. I could see clearly what was happening.

Earlier that day, I had spoken out in a meeting with my team at CBC News Network—the broadcaster’s 24 hour television news channel. It was six weeks into Israel’s siege and bombardment of the Gaza Strip, which had, at the time, killed over 11,000 Palestinians, the majority of them women and children. Legal experts were already suggesting that what was taking place could be a “potential genocide,” with an Israeli Holocaust scholar calling it “a textbook case.”

I expressed concern to my team about the frequency of Palestinian guests getting cancelled, the scrutiny brought to bear on their statements, and the pattern of double standards in our coverage. After this, I pitched a reasonable and balanced interview: two genocide scholars with opposing views discussing whether Israel’s actions and rhetoric fit the legal definition of the crime.

Senior colleagues sounded panicked. My executive producer replied that we had to be ”careful not to put hosts in a difficult position.” They wanted time to consult with higher-ups before making a decision. A few hours later, I was sitting across from the same executive, being warned about “crossing the line.”

The following afternoon, I showed up for what was supposed to be a typical meeting to go over the interviews we had lined up for the coming days—but some unusual guests were present. In addition to my co-workers, the faces of my executive producer and his higher-ups appeared on Google Meet.

The managers were there to talk about my pitch. They said they weren’t vetoing it—they weren’t meant to even make editorial decisions—but suggested our show wasn’t the best venue. I pointed out that the network was deemed a suitable place for interviews with guests who characterized Russia’s war on Ukraine and China’s oppression of the Uighurs as instances of genocide. The managers looked uncomfortable. I was reassigned to work on a panel with two guests calling on the West to support regime change in Moscow and Tehran. (Ever since these unusual meetings had started, I was recording them for my protection.)

IF JOURNALISTS IN GAZA WERE SACRIFICING THEIR LIVES TO TELL THE TRUTH, I SHOULD AT LEAST BE PREPARED TO TAKE SOME RISKS.

But that wasn’t the end of the blowback. The next week, late on a Friday afternoon, I received an email from the same two managers who had poured cold water on my pitch. They needed to speak to me urgently. Over the phone, I was asked to keep the conversation secret.

They told me I had hurt the feelings of some of my co-workers. But it was more than just hurt feelings: someone was accusing me of antisemitism.

I had, it appeared, “crossed the line.”

Trying to work your way up to a permanent position at Canada’s public broadcaster requires knowing the sort of stories, angles and guests that are acceptable—and which are out of bounds. As a precarious “casual” employee—a class of worker that makes up over a quarter of CBC’s workforce—it hadn’t taken me long to realize that the subject of Israel-Palestine was to be avoided wherever possible. When it was covered, it was tacitly expected to be framed in such a way as to obscure history and sanitize contemporary reality.

After October 7, it was no longer possible for the corporation to continue avoiding it. But because CBC had never properly contextualized the world’s longest active military occupation in the lead-up to that atrocity, it was ill-equipped to report on what happened next.

The CBC would spend the following months whitewashing the horrors that Israel would visit on Palestinians in Gaza. In the days after Israel began its bombing campaign, this was already evident: while virtually no scrutiny was applied to Israeli officials and experts, an unprecedented level of suspicion was being brought to bear on the family members of those trapped in Gaza.

My job required me to vet the work of associate producers and to oversee interviews, so I was well-positioned to see the double standards up close.

At first, out of concern that it would jeopardize my chances of landing a staff job that I had recently applied for, I only voiced mild pushback. But as the death toll mounted, my career started to seem less important. If journalists in Gaza were sacrificing their lives to tell the truth, I should at least be prepared to take some risks.

Besides, I naively told myself, it would be easier for me to dissent than most of my colleagues. I am of mixed Jewish heritage, having been raised by a father who fled the Holocaust as a young child and dealt with the life-long trauma and guilt of surviving while his family members were murdered by the Nazis. It would be more challenging, I believed, for cynical actors to wield false accusations of antisemitism against me.

I turned out to be wrong.

The Palestine exception at CBC

In the run-up to Oct. 7, a senior colleague said that if we were lucky, “the news gods would shine on us” and put an end to a stretch of “slow news” days. Waking up on that fateful Saturday to multiple alerts on my phone, I knew that both the world and my professional life were about to dramatically change.

Even before Oct. 2023, trying to persuade senior CBC colleagues to report accurately on Palestinians was a struggle. Here are some of the TV interview ideas that a colleague and I pitched but had turned down: Human Rights Watch’s 2021 report designating Israel an apartheid state; the Sheikh Jarrah evictions in the same year; Israel assassinating Palestinian-American journalist Shireen Abu Akleh in 2022; and the Israeli bombing of the Jenin refugee camp in July 2023.

The last of these ideas was initially greenlit but was later cancelled because a senior producer was concerned that the host would have too much on her plate. Around this time, I also pitched someone from the Israeli human rights organization B’Tselem to talk about the potential impact of widely-protested judicial reforms on Palestinians—but this was nixed for fear of complaints. These would become familiar excuses.

After October 7, I dreaded going into work: every shift, the impact of the biases went into overdrive. Even at this early stage, Israeli officials were making genocidal statements that were ignored in our coverage. On October 9, Defence Minister Yoav Gallant said, “I have ordered a complete siege on the Gaza Strip. There will be no electricity, no food, no fuel; everything is closed. We are fighting human animals and we act accordingly.” Even after this comment, my executive producer was still quibbling over uses in our scripts of the word “besieged” or references to the “plight of Palestinians.”

On October 20, I suggested having Hammam Farah, a Palestinian-Canadian psychotherapist, back on the network. In an earlier interview he had told us that his family were sheltering in Saint Porphyrius Greek Orthodox church in Gaza City. The following week, I learned from social media that his step-cousin had been killed in an Israeli airstrike on the 12th-century building. My executive producer responded to my pitch via instant message: “Yeah, if he’s willing. We also may have to potentially say we can’t verify these things though—unless we can.”

I was stunned. Never in my nearly 6 years at CBC had I ever been expected to verify the death of someone close to a guest, or to put a disclaimer in an interview that we couldn’t fact-check such claims. That’s not a standard that producers had been expected to uphold—except, apparently, for Palestinians.

Besides, even at that early stage, civil society had completely broken down in Gaza. I couldn’t just call up the health authority or courthouse to ask that they email over a death certificate. I already had Farah’s relative’s full name and had found a Facebook profile matching a commemorative photo he had posted on Instagram. This was already more verification than I had done for Israeli interviewees who had loved ones killed on October 7. A few days later, a different program on the network aired an interview with the guest using passive language in the headline: “Toronto man says relative was killed in airstrike that hit Gaza.”

I was being forced to walk a tightrope, trying to retain some journalistic integrity while keeping my career intact.

In early November, I was asked to oversee production of an interview with a former US official now working for the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, a pro-Israel think tank.

During the interview, he was allowed to repeat a number of verifiably false claims live on air—including that Hamas fighters had decapitated babies on October 7 and that Gazan civilians could avoid being bombed if only they listened to the Israeli military and headed south. This was after civilian convoys fleeing southward via “safe routes” had been bombed by the Israeli military before the eyes of the world.

As soon as I heard this second falsehood, I messaged my team suggesting that the host push back—but received no response. Afterwards, the host said she had let the comment slide because time was limited, even though she could have taken the time from a less consequential story later on in the program.

The majority of Palestinian guests I spoke to during the first six weeks of Israel’s assault on Gaza all said the same thing: they wanted to do live interviews to avoid the risk of their words being edited or their interview not being aired. These were well-founded concerns.

Never before in my career had so many interviews been cancelled due to fear of what guests might say. Nor had there ever been direction from senior colleagues to push a certain group of people to do pre-taped interviews. (CBC told The Breach it “categorically rejects” the claim that interviews were “routinely cancelled”.)

On another occasion in November, a Palestinian-Canadian woman in London, Ontario named Reem Sultan, who had family trapped in the Strip, was scheduled for one such pre-taped interview. Because of her frustration over previous interviews that she had given and coverage of her family’s situation being “diluted,” she asked if she could go live instead.

When I asked the senior producer, he looked uneasy and said the interview should be cancelled, citing that the guest had already been on the network that week. I agreed that it would be preferable to interview a new Palestinian voice and said I had contact information for a number of alternative guests. However, after cancelling the interview with Sultan, the senior producer informed me that he didn’t want another guest after all.

Editing out ‘genocide’

Most shows on the network seemed to avoid airing any mention of “genocide” in the context of Gaza.

On November 10, my senior producer pushed to cancel an interview I had set up with a Palestinian-Canadian entrepreneur, Khaled Al Sabawi. According to his “pre-interview”—a conversation that typically happens before the broadcastable interview—50 of his relatives had been killed by Israeli soldiers.

The part of the transcript that concerned the senior producer was Al Sabawi’s claim that Netanyahu’s government had “publicly disclosed its intent to commit genocide.” He also took issue with the guest’s references to a “documented history of racism” and “apartheid” under Israeli occupation, as well as his suggestion that the Canadian government was complicit in the murder of Gazan civilians.

The senior producer raised his concerns via email to the executive producer, who then cc’ed one of the higher-up managers. The executive producer replied that it “sound[ed] like [his statement was] beyond opinion and factually incorrect.” The executive manager’s higher up chimed in, saying she thought the interview would be “too risky as a pre-tape or live [interview].”

Despite the guest’s position aligning with many UN experts and Western human rights organizations, the interview was cancelled. (CBC told The Breach “the guest turned down our offer of a pre-taped interview,” but Al Sabawi had said to the producers from the start that he would only do a live interview.)

NEVER IN MY NEARLY 6 YEARS AT CBC HAD I EVER BEEN EXPECTED TO VERIFY THE DEATH OF SOMEONE CLOSE TO A GUEST. THAT’S NOT A STANDARD THAT PRODUCERS HAD BEEN EXPECTED TO UPHOLD—EXCEPT, APPARENTLY, FOR PALESTINIANS.

In another instance, a Palestinian-Canadian guest named Samah Al Sabbagh, whose elderly father was then trapped in Gaza, had part of her pre-taped interview edited out before it went to air. She had used the word “genocide” and talked about the deliberate starvation of Palestinians in Gaza. The senior producer told me the edit was because of time constraints. But that producer and the host were overheard agreeing that the guest’s unedited words were too controversial. (CBC told The Breach it “has not ‘cancelled’ interviews with Palestinians because they reference genocide and apartheid.”)

By November 2023, it was getting harder to ignore the brazen rhetoric coming from senior Israeli officials and the rate of civilian death, which had few precedents in the 21st century. But you wouldn’t have heard about these things on our shows, despite a number of producers’ best efforts. (By early 2024, the International Court of Justice’s hearings—and later its ruling that Israel refrain from actions that could “plausibly constitute” genocide—forcibly changed the discussion, and the word “genocide” finally made some appearances on CBC.)

But back in late October, I booked an interview with Adel Iskandar, Associate Professor of Global Communication at Simon Fraser University, to talk about language and propaganda from Israeli and Hamas officials. The host filling in that day was afraid of complaints, was concerned about the guest wanting to be interviewed live, and judged him to be biased. Yet again an interview was cancelled.

A secret blacklist?

One Saturday in mid-October, I arrived at work shortly after the airing of an interview with the prominent Palestinian-Canadian lawyer and former spokesperson for the Palestine Liberation Organization, Diana Buttu.

There had been a commotion, I was told. A producer from The National—the CBC’s flagship nightly news and current affairs program—had apparently stormed into the newsroom during the interview saying that Buttu was on a list of banned Palestinian guests and that we weren’t supposed to book her.

I heard from multiple colleagues that the alleged list of banned Palestinian guests wasn’t official. Rather, a number of pro-Israel producers were rumoured to have drawn up their own list of guests to avoid.

Later, I was told by the producer of the interview that, after the broadcast, Buttu’s details had mysteriously vanished from a shared CBC database. By then, I had also discovered that the name and contact details for the Palestinian Ambassador Mona Abuamara, who had previously been interviewed, had likewise been removed. It didn’t seem coincidental that both guests were articulate defenders of Palestinian rights.

While producers distressed by the CBC’s coverage of Gaza were speaking in whispers, pro-Israeli colleagues felt comfortable making dehumanizing comments about Palestinians in the newsroom.

In one case, I heard an associate producer speak disparagingly about a guest’s decision to wear a keffiyeh for an interview before commenting that “[the host] knows how to handle these people.” This guest had dozens of family members killed by the Israeli military in Gaza.

It seemed the only Palestinian guest CBC was interested in interviewing was the sad, docile Palestinian who talked about their suffering without offering any analysis or solutions to end it. What they did not want was an angry Palestinian full of righteous indignation towards governments complicit in their family’s displacement and murder.

At this stage, I was starting to feel nauseous at work. And then one Saturday night, that sickness turned into anger.

I had been asked to finish production on a pre-taped interview with a “constructive dialogue” researcher on incidents of campus hostilities over the war and how to bring people together—the sort of interview CBC loves, as it’s a way to be seen covering the story without actually talking about what’s happening in Gaza.

I carried out the task in good faith, writing an introduction leading with an example of antisemitism and then another of anti-Palestinian hate, taking care to be “balanced” in my approach. But my senior producer proceeded to remove the example of anti-Palestinian hate, replacing it with a wishy-washing “both sides” example, while leaving the specific serious incident of antisemitism intact. He also edited my wording to suggest that pro-Palestinian protesters on Canadian campuses were on the “side” of Hamas.

I overheard the host thank the senior producer for the edits, on the basis that incidents of antisemitism were supposedly worse. While the introduction of these biases into my script was relatively minor compared to some other double standards I witnessed, it was a tipping point.

I challenged the senior on why he had made my script journalistically worse. He made up a bad excuse. I told him I couldn’t do this anymore and walked out of the newsroom, crying.

Truth-telling about CBC

That evening at home, the nausea and the anger dissolved, and for the first time in six weeks I felt a sense of peace. I knew it was untenable to stay at CBC.

At a team meeting the following week, in mid-November, I said the things I had wanted to say since the start of Israel’s assault on Gaza.

I prefaced the conversation by saying how much I loved my team and considered some coworkers friends. I said the problems weren’t unique to our team but across the CBC.

But the frequency of Palestinian guests getting cancelled, the pressure to pre-tape this one particular group, in addition to the unprecedented level of scrutiny being placed on them, demonstrated a pattern of double standards. I said there seemed to be an unspoken rule around words like “genocide.”

I pointed out that Arab and Muslim coworkers, especially those who were precariously employed, were scared of raising concerns, and that I and others had heard dehumanizing comments about Palestinians in the newsroom. (The CBC told The Breach that there “have been no specific reports of anti-Palestinian and Islamophobic comments in the newsroom for managers to respond to or follow up”.)

I said that two decades since the US-led invasion of Iraq, it was widely-acknowledged that the media had failed to do their jobs to interrogate the lies used to justify a war and occupation that killed one million Iraqis—and that as journalists we had a special responsibility to tell the truth, even if it was uncomfortable.

A couple of coworkers raised similar concerns. Others rolled their eyes. (CBC told The Breach that it doesn’t recall there was anyone else who raised concerns in the meeting, but audio recordings show otherwise.)

The question of why there was nervousness around this issue came up. I said one reason why we were adverse to allowing Palestinian guests to use the “G-word” was because of the complaint campaigns of right-wing lobby groups like HonestReporting Canada.

Indeed, in just 6 weeks, there were already 19 separate instances of HonestReporting going after CBC journalists, including a host on our team. HonestReporting had also claimed responsibility for the firing at two other outlets of two Palestinian journalists, one of whom was on maternity leave at the time.

All this had a chilling effect. Hosts and senior colleagues would frequently cite the threat of complaints as a reason not to cover Israel-Palestine. During my time there, a senior writer was even called into management meetings to discuss her supposed biases after a HonestReporting campaign targeted her. Her contract was cut short.

This policing of media workers’ output reinforced existing institutional tendencies that ensured CBC rarely deviated from the narrow spectrum of “legitimate” opinions represented by Canada’s existing political class.

Certain CBC shows seemed to be more biased than others. The National was particularly bad: the network’s primetime show featured 42 per cent more Israeli voices than Palestinian in its first month of coverage after the Oct. 7 Hamas attack, according to a survey by The Breach.

Although some podcasts and radio programs seemed to cover the war on Gaza in a more nuanced way, the problem of anti-Palestinian bias in language was pervasive across all platforms.

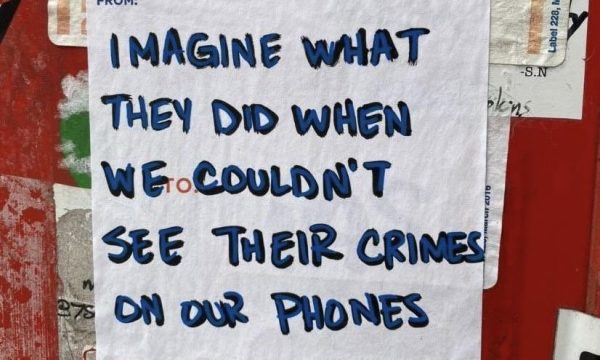

According to an investigation in The Breach, CBC even admitted to this disparity, arguing that only the killing of Israelis merited the term “murderous” or “brutal” since the killing of Palestinians happens “remotely.” Images of children being flattened to death in between floors of an apartment building and reports of premature babies left to starve in incubators suggested otherwise.

IT SEEMED THE ONLY PALESTINIAN GUEST CBC WAS INTERESTED IN INTERVIEWING WAS THE SAD, DOCILE PALESTINIAN WHO TALKED ABOUT THEIR SUFFERING WITHOUT OFFERING ANY ANALYSIS OR SOLUTIONS TO END IT.

I spoke to many like-minded colleagues to see if there was any action we could all take to push back on the tenor of our coverage, but understandably others were reluctant to act—even collectively—out of fear doing so would endanger their jobs. Some of those colleagues would have loved to have walked out, but financial responsibilities stopped them.

There had been previous attempts at CBC to improve the public broadcaster’s coverage of Israel-Palestine. In 2021, hundreds of Canadian journalists signed an open letter calling out biases in the mainstream media’s treatment of the subject.

A number of CBC workers who signed the letter were hauled into meetings and told they either weren’t allowed to cover the subject or would have any future work on the issue vetted. A work friend later regretted signing the letter because she got the sense that she had been branded as biased, leading to her pitches on Palestine being more readily dismissed.

Smeared as antisemitic

In mid-November, after laying out my concerns to my colleagues, the regular weekly pitch meeting took place. It was then that I pitched the two genocide scholars, before having to attend that virtual meeting with my executive producer—where he suggested I go on mental health leave—and yet another meeting with two managers who raised concerns over my pitch the next day. But the most unpleasant meeting with management was about to come.

A week later, I was accused of antisemitism on the basis of something I didn’t even say. According to a manager, someone had accused me of claiming that “the elephant in the room [was] the rich Jewish lobby.” (CBC told The Breach that “employees expressed concerns” that what she said was “discriminatory”.)

The accusation was deeply painful because of my Jewish heritage and how my dad’s life—and, as a consequence, my own—was profoundly damaged by antisemitism. But I also knew I could prove that it was baseless: I had recorded what I said, anxious that someone might twist my words to use them against me.

What I had actually said, verbatim, was this:

“I just want to address the elephant in the room. The reason why we’re scared to allow Palestinian guests on to use the word ‘genocide’ is because there’s a very, very well funded [sic], there’s lots of Israel lobbies, and every time we do this sort of interview, they will complain, and it’s a headache. That’s why we’re not doing it. But that’s not a good reason not to have these conversations.”

I stand by my statement. HonestReporting Canada is billionaire-funded. In December 2023, HonestReporting bragged about having “mobilized Canadians to send 50,000 letters to news outlets.” The group has also published a litany of attacks on journalists at CBC and other publications who’ve done accurate reporting on Palestine, and created email templates to make it easier for their followers to complain to publications about specific reporters.

Other, similar pro-Israel groups like the Committee for Accuracy in Middle East Reporting in America (CAMERA) and the Canary Mission employ similar tactics to try to silence journalists, academics, and activists who tell the truth about Israel-Palestine.

I told the manager it was telling that instead of following up on the racist comment I had heard from colleagues about Palestinians, I was the one being accused of antisemitism and discrimination—on the basis of words I hadn’t even uttered.

The banality of whitewashing war crimes

When I handed in my resignation notice on November 30, I felt relieved that I was no longer complicit in the manufacturing of consent for a genocidal war of revenge.

Despite my experience, I still believe in the importance of the national broadcaster to act in the public interest by reporting independently of both government and corporate interests, presenting the truth and offering a diverse range of perspectives.

However, I believe that CBC has not been fulfilling these duties when it comes to its coverage of Israel-Palestine. I believe that in the future, historians will examine the many ways that CBC, and the rest of mainstream media, have all failed to report truthfully on this unfolding genocide—and in doing so likely accelerated their delegitimization as trusted news sources.

Before resigning, I raised the issue of double standards with various levels of the CBC hierarchy. While some members of management pledged to take my concerns seriously, the overall response left me disappointed with the state of the public broadcaster.

After my appeal to my coworkers in mid-November, I had a phone conversation with a sympathetic senior producer. He said he didn’t think my words at the meeting would interfere with my chances of getting the permanent staff job I had long dreamed of. Despite this assurance, I was certain that I wouldn’t get it now: I knew I’d crossed the line for saying out loud what many at CBC were thinking but couldn’t say openly. Indeed, I wouldn’t have spoken out if I hadn’t already decided to resign.

As a kid, I had fantasies of shooting Hitler dead to stop the Holocaust. I couldn’t fathom how most Germans went along with it. Then, in my 20s, I was gifted a copy of Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann In Jerusalem: A Report On The Banality Of Evil by anti-Zionist Israeli friends. I’ve been thinking a lot about that piece of reportage when trying to make sense of the liberal media’s complicity in obfuscating the reality of what’s happening in the Holy Land. As Arendt theorized, those who go along with genocides aren’t innately evil; they’re often just boring careerists.

To be sure, while there are a number of senior CBC journalists who are clearly committed to defending Israel no matter its actions, many journalists just follow the path of least resistance. The fact that permanent, full-time CBC jobs are in such short supply, combined with threats of looming cuts, only reinforces this problem.

I still hear from former colleagues that pitch meetings are uphill battles. Some shows are barely covering Gaza anymore.

Being a journalist is a huge privilege and responsibility, especially in a time of war. You’re curating the news for the audience; deciding which facts to include and which to omit; choosing whose perspectives to present and whose to ignore. I believe that a good journalist should be able to turn their critical eye, not just on the news, but on their own reporting of the news. If you’re unable to do this, you shouldn’t be in the profession.

I purposefully haven’t given away identifiable information about my former colleagues. Ultimately, this isn’t about them or me: it’s part of a much wider issue in newsrooms across the country and the Western world—and I believe it’s a moral duty to shed a light on it. If I didn’t, I’d never forgive myself.

Just as I’m not naming my colleagues, I’m writing this using a pseudonym. Although the spectrum of acceptable discourse continues to shift, the career consequences for whistleblowers on this issue remains formidable.

I encourage fellow journalists who refuse to participate in the whitewashing of war crimes, especially those with the security of staff jobs, to speak to like-minded coworkers about taking collective action; to approach your union steward and representative; and to document instances of double standards in your newsrooms and share them with other media workers.

It was scary, but I have no regrets about speaking out. My only regret is that I didn’t write this sooner.

Molly Schumann is a pseudonym for a former TV and radio producer who worked at CBC for 5 years.